Home Page Discussion

The Salon du Tapis d'Orient is a moderated discussion group in the manner of the 19th century salon devoted to oriental rugs and textiles and all aspects of their appreciation. Please include your full name and e-mail address in your posting.

Rugs and Old Masters: Part 2 - Geometric Rugs in Early Renaissance

(14th and 15th Century) Paintings.

by Pierre Galafassi

Animal rugs were sometimes used as studio props for

early Renaissance paintings (14th and 15th century) but were not the

main type of rug at the time. Most carpets featured in

paintings of the period have purely geometric field motifs, which are

often unfamiliar to us and even puzzle the very few scholars who have

studied them. In many cases there is no extant rug featuring

these patterns. It is generally agreed that these rugs were

mostly woven in the Islamic world, in the large crescent from Anatolia

and Egypt to Maghreb and Al-Andalus (southern Spain).

However, scholars are rarely more specific than that.

I have made a feeble attempt at dividing these rugs based on their motifs.

A first group

are very small rugs featured in a fairly large number of early

paintings, mainly of the schools of Florence, Siena, Venice and

Ferrara, often depicted as decorations for windowsills and gondolas

during festivals (1). John Mills (2) thinks that their “geometric

designs look like highly simplified versions of Turkish rugs of the

second half of the (15th) century. Whether they were in fact early

versions of these or were locally made in imitation of them cannot be

certainly decided, but the latter does seem the more likely”.

As

a possible location for the workshops, a few southern Italian cities,

like Lucera (Puglia region) have been tentatively mentioned by some

sources, mainly owing to the fact that part of their population was

Muslims expelled from Sicily by Frederik II Hohenstaufen. Mills’ theory

of Italian copies is credible of course, but one could just as well

suspect Muslim populations of Sicily, Spain (as suggested by Giovanni

Curatola (3)) or Anatolia, (Walter. B. Denny (4)), to have woven them.

FIG 28

A. di Giovanni 1440-1460.

Cassone ( marriage chest) panel with scenes of tournament.

National Gallery London

FIG 29

A. Baldovinetti.Madonna and Child.

Uffizi. Florence.

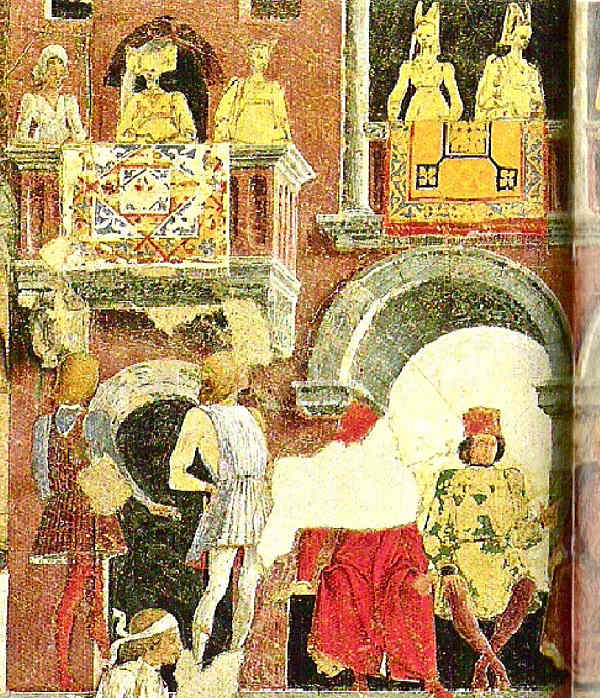

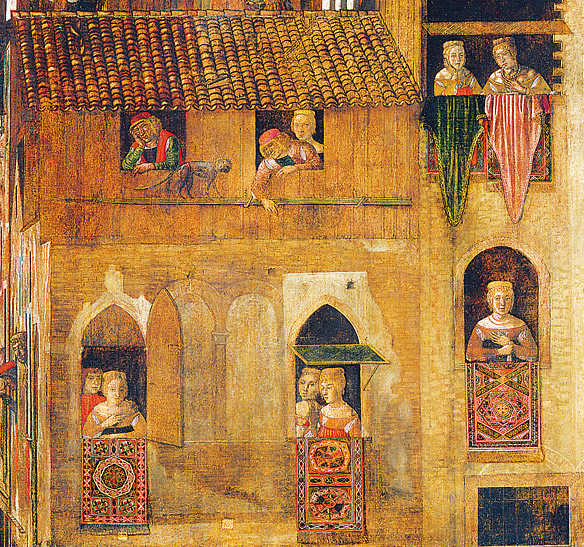

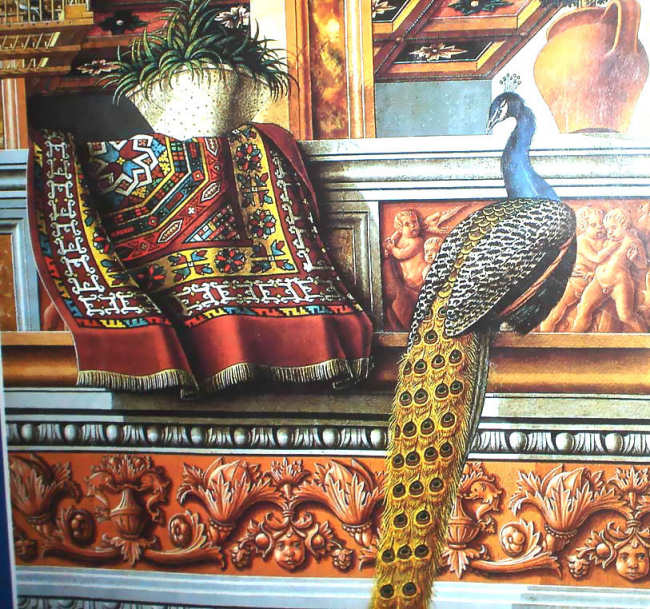

FIG 31

G. del Cossa. 1476-1484.

Allegory of April, detail.

Palazzo Schifanoia. Ferrara.

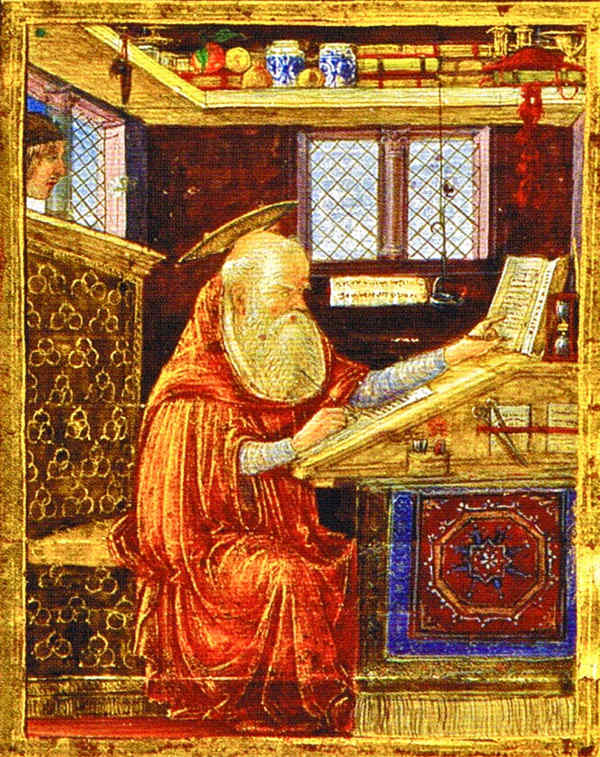

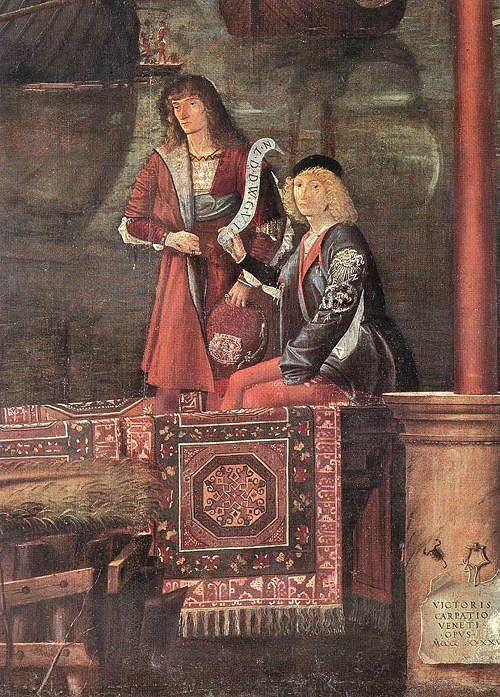

FIG 35 & FIG 36

V. Carpaccio. 1495.

Two details from the «Cycle of St Ursula, the departure of the pilgrims»

Accademia. Venice.

A

second group of rugs features geometrical patterns which, contrary to

most of those shown above, do not strike me as being particularly

“Turkish”. Their inspiration could just as well be European, Armenian

or Byzantine, for example. Onno Ydema (5) states that the undulating

“curvilinear stem with trefoil leaves (in the border) is almost

certainly derived from Western Gothic ornament”. The rugs are evidently

more densely knotted than the previous group, feature a normal border

and come in various sizes similar to those in later classical rugs.

About ten different rugs of this type can be seen in J. van Eyck’s, G.

David’s and Petrus Christus’ paintings. The strong similarities

of the motifs make a common origin very likely. To my limited

knowledge, no rug with such motifs is extant; thus, we have little

reason to expect that a structural analysis could give us clues to

their real origin.

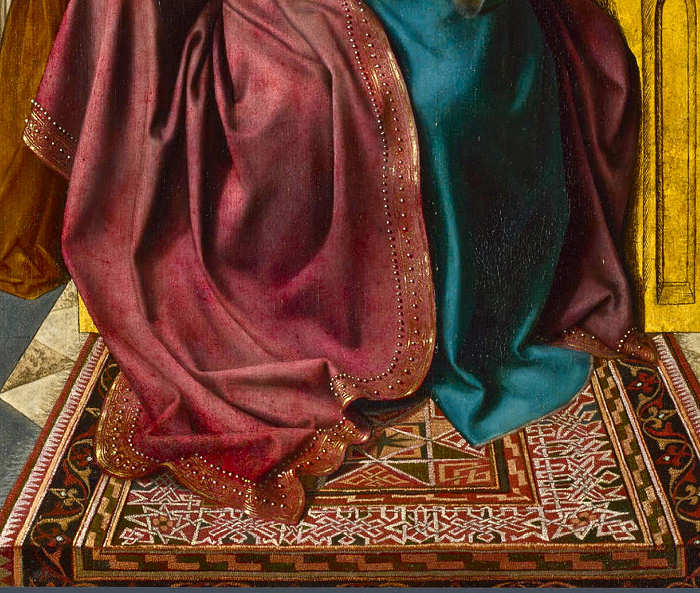

FIG 39

J. van Eyck. 1436.

The Lucca Madonna.

Frankfurt.

A

third group of early paintings features rugs that can be clearly linked

to classical Anatolian patterns which were successfully copied and

expanded over the next few centuries. Especially so-called “small

pattern Holbein”, “large pattern Holbein”, “Para-Mamluk”, “Bellini” and

“Ghirlandaio” rugs. Many were used as studio props in paintings, and

even a few 15th century rugs are extant.

Four of the

oldest representations of “small pattern Holbein rugs” are found in

paintings by A. Mantegna, B. Baró, S. Botticelli and T. del Trombetto.

FIG 43

A. Mantegna. 1457-1459.

Virgin and Child. Detail.

San Zeno altarpiece. Verona

FIG 44

B. Baró 1450-1470

Virgen de la leche.

Ademuz. Spain.

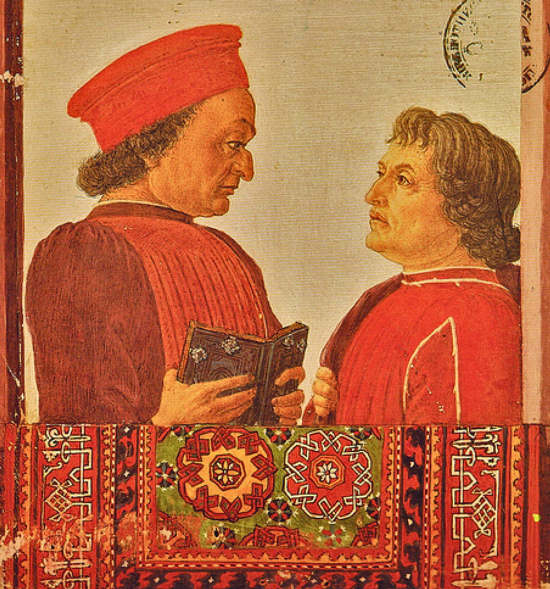

FIG 45

S. Botticelli. 1460.

F. de Montefeltre and Landino.

Vatican.

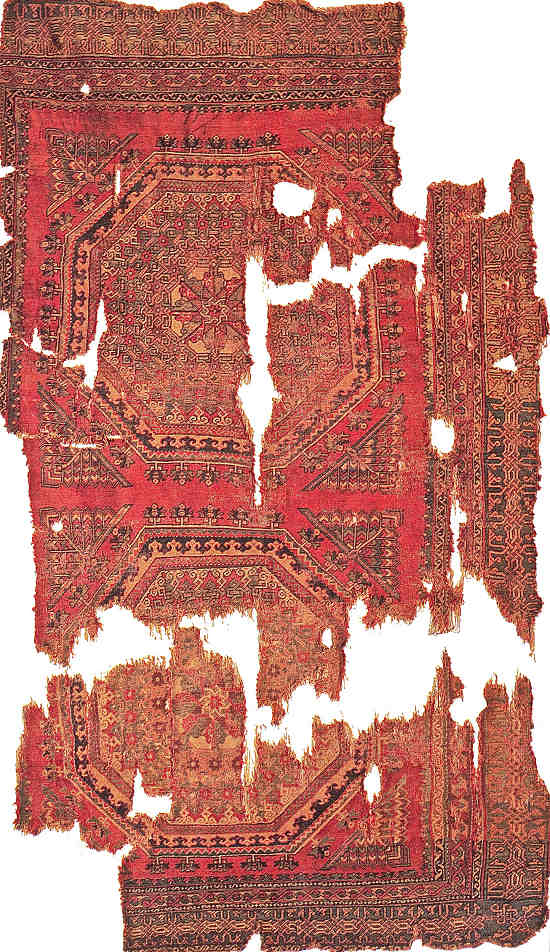

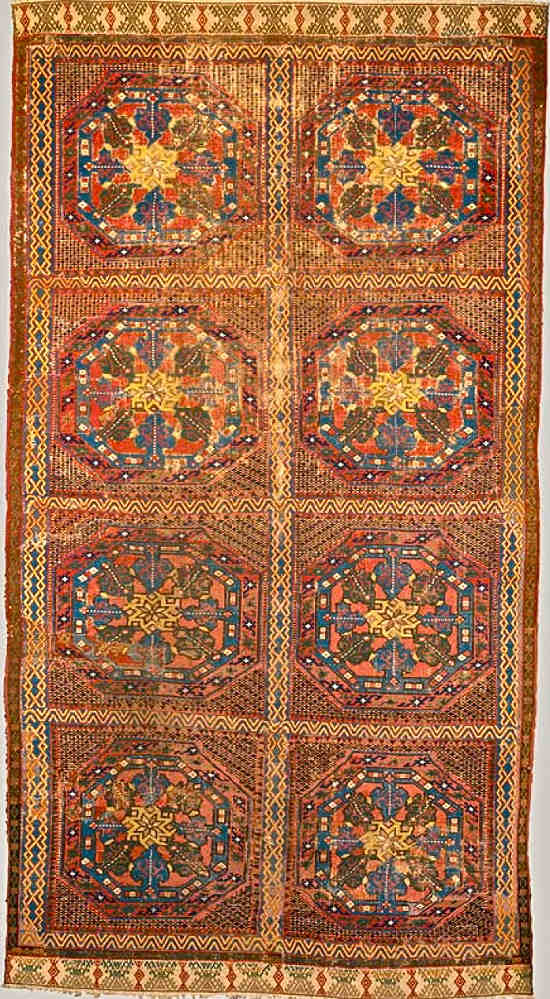

FIG 46 and FIG 47

Anatolian

rugs with «small Holbein» pattern. 15th

century.

In «Anatolian Carpets», W. B Denny. (FIG 46)

& in «Vakiflar Museum. Teppiche», B. Balpinar & U. Hirsch (FIG 47)

FIG 48 shows, arguably, the first representation of a Ghirlandaio pattern:

The first “para-mamluk” rugs were probably painted by F. Foppa and by Giovanni da Udine.

FIG 49

V. Foppa. 1485.

Virgin and Child. Detail.

Brera. Milan

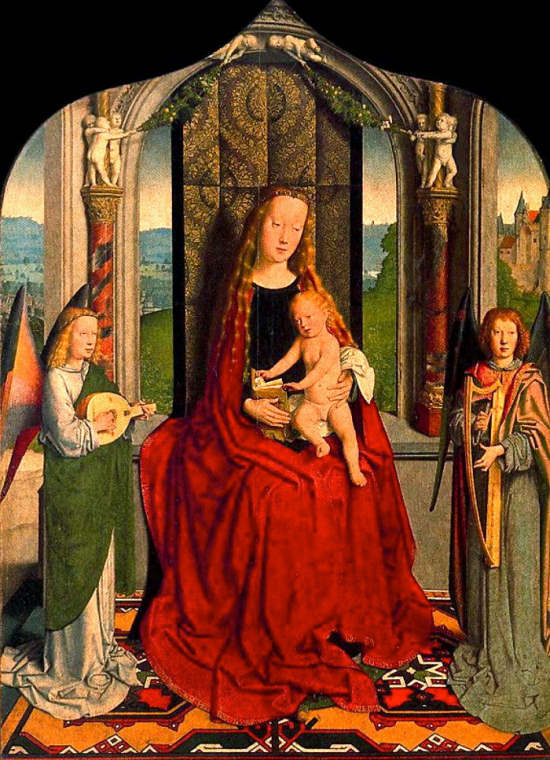

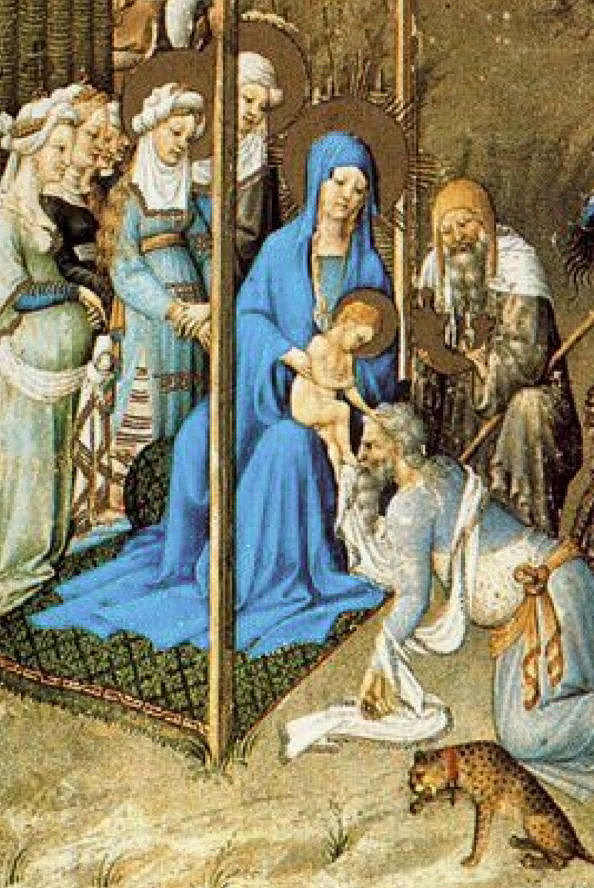

The eponymous ancestor of the famous “Bellini” rug of the MIK in

Berlin (FIG 52) appears under the throne of the Virgin in a 1470

painting (FIG 51).

There are few extant “sober Bellini rugs”, none

with this border (6), but the single- and double “keyhole” (or

“re-entrant”) pattern remained a favorite of Turkish weavers for

another several centuries (for example, FIG 53).

FIG 51

Gentile Bellini 1470.

Virgin and Child.

National Gallery, London

FIG 52

Ushak prayer rug with «Bellini» pattern.

16th century

Museum für Islamische Kunst. Berlin.

The

so-called “large Holbein” pattern might have been first featured in a

well known Crivelli painting, FIG 54. According to Mills, the origin of

the pattern might be in northwestern Anatolia (7)

The

rug in Crivelli’s painting looks like a smaller, simplified version of

the roughly contemporaneous extant rug in FIG 55, given as 14th or 15th

century. There is also a clear pattern analogy with the 15-16th century

southern Spanish rug in FIG 56 and several other extant Spanish carpets.

FIG 55

Anatolia. 14th-15th century.

Vakiflar Museum, Teppiche, B. Balkinar & U.Hirsch.

This

leads us to a fourth group of 14th and 15th century rugs, featured in

Spanish paintings and quite possibly woven in southern Spain. It

is well documented that rugs have been produced since the Muslim

conquest in this region, mainly in Alcaraz, Letur, Chinchilla, Cuenca,

Alpujara and Murcia, and that production continued long after the

Christian Reconquista was completed in 1494, and even after a large

part of the Muslim population was forced to emigrate (8).

Several

Moslem writers praised the outstanding quality of Al-Andalus rugs, for

example Ibn Hawkal (10th century) and Al-Idrissi (12th century).

Al-Saqundi (12th century) boasts that these rugs were “exported to all

countries of Orient and Occident”, Cairo being a particularly good

customer. When Leonor de Castilla married the future King Edward I of

England in 1254, the young bride had a main street of London decorated

with her many Spanish rugs (8).

Nearly three centuries later, Henry

VIII’s chancellor, Cardinal Wolsey, still appreciated and collected

Spanish rugs (we will say more about this fanatical ruggie in our next

essay.)

Spanish weavers used a specific knot, shared only with some

Egyptian (coptic?) weavers. Thus, the attributions of extant

Spanish rugs are reasonably certain despite the strong analogy of many

motifs with those of Anatolia.

FIG 57

J. Huguet. 1460.

St Vincent ordained by St Valerius

MNAC. Barcelona.

FIG 59

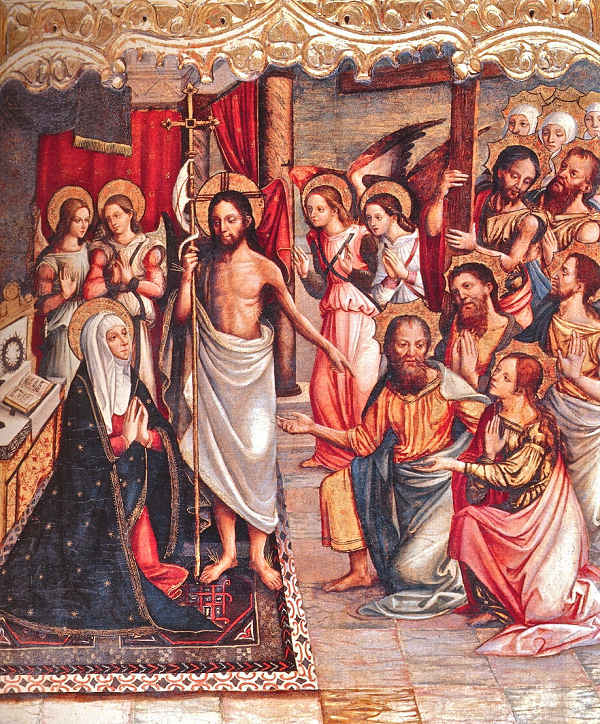

V. Macip. 1480-1500.

Christ resuscitated.

Valencia Cathedral

Note the curvilinear pattern inscribed in hexagons (Renaissance influence?) and the narrow (mudejar?) kufic border of FIG 60.

Many

rugs shown in fourteenth- and fifteenth century paintings feature

unique patterns which fully defeat my occidental urge for classifying

all and everything. Unless I err, most of these orphan carpets do not

even have any extant descendants, poor lonely chaps.

One cannot

exclude that a few rugs were the fruit of the painters imagination, but

most look quite credible, at least to my uneducated eyes. The scholar,

R.A. Mack states that “The Italian elite who commissioned paintings

showing their costly carpets undoubtedly wanted them represented in

details” (9).

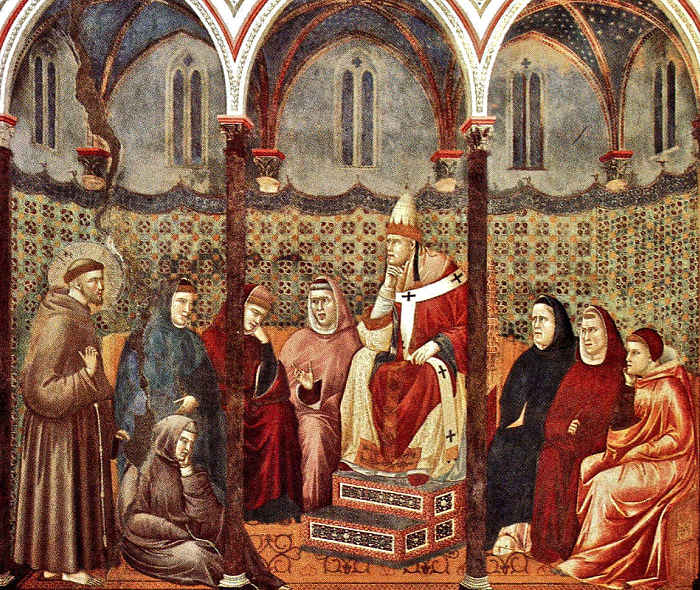

FIG 62

Giotto di Bondone.

1290-1300

St Francis & Honorius III

Detail.

Assisi Basilica.

Quiz

for our many Turkotek rug experts: Is the rug in FIG 63 a kilim?

A rug made sewing together bands of flat weaves like tent bands?

The

field of the “Arnolfini rug” (FIG 64) appears to be woven in parallel

bands featuring the same four motifs on a surmey background. Mills does

not exclude the possibility that it could be a local needlework

(10). The “Sedano” rug (FIG 66) seems to be a variation of the

“large Holbein” pattern.

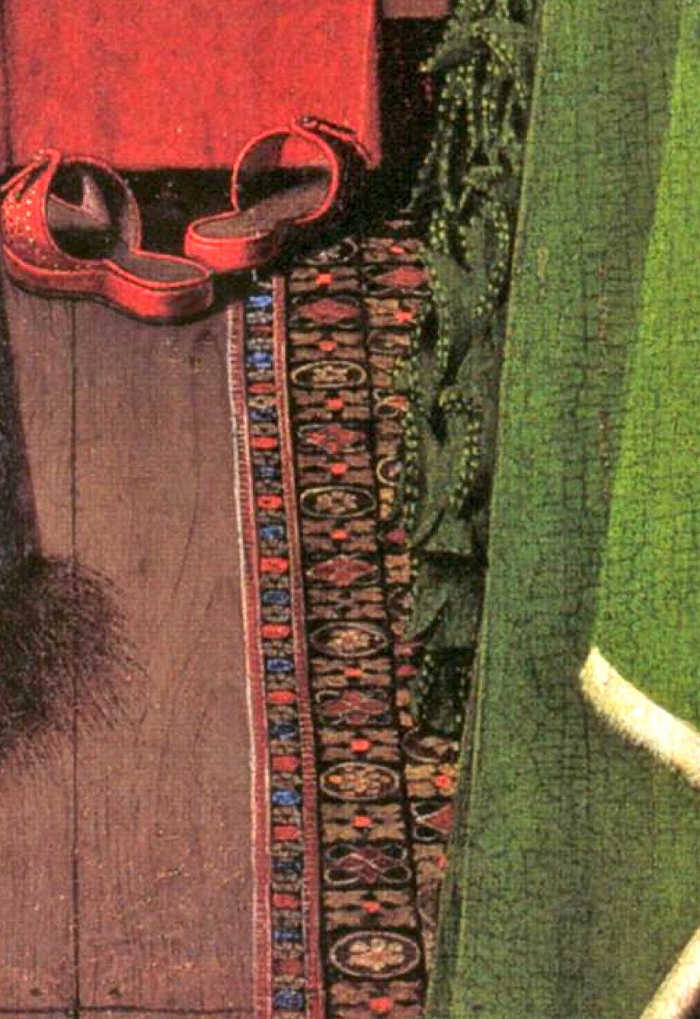

FIG 64

J.

van Eyck.

1434

Portrait of G. Arnolfini and his wife.

Detail

National Gallery. London.

FIG 66

G. David 1490-1495

The Sedano Virgin. Detail.

Louvre. Paris

Massy’s

rug (FIG 67) particularly puzzles John Mills (11): “...the elaborate

border of kufic plus endless knot resembles known Turkish borders of

the period, but the exactly contrived solution to the problem of

turning the corners is most unusual, the field design is not a

recognizable one and the curvilinear border accords ill with the

otherwise starkly geometrical border...”

I find the rug in the

French miniature (FIG 68) quite interesting too, with its sober

two-tone indigo field much reminiscent of some earlier Seldjuk rugs

except for the fact that the small repeating motif here is a cross.

My

puzzle-o-meter hits its highest marks with FIG 69, a painting by A. del

Castagno, and with FIG 70, an Il-Khanid (12) miniature from early 14th

century with its field of repeating endless knots and sophisticated

borders, including one kufic.

FIG 69

A. del Castagno. 1445.Virgin & Child.

The Pazzi Madonna

Uffizi. Florence

You

may have noticed the scandalous absence of Memling in this essay.

Indeed this rug-obsessed artist was also very active during the last

quarter of the fifteenth century, but abusing our authority as authors

of this essay, we opted to tell you soon «a tale of two ruggies.

1475-1540» starring Memling and Holbein.

Sources and notes.

(1) Rosamond E. Mack, Bazaar to Piazza, page 78

(2) John Mills, Carpets in Paintings, 1983, pages 11-14.

(3) Giovanni Curatola, in Venise et l’Orient, Tissus et tapis à Venise, page 210. Gallimard. 2006.

(4) Walter. B. Denny, in «Venise et l’Orient», Textiles et tapis d’orient à Venise, page 178. Gallimard. 2006.

(5) Onno Ydema, Carpets in Netherlandish paintings, page 9. (*)

(6) John Mills, carpets in Paintings, 1983, page 20.

(7) John Mills, carpets in Paintings, 1983, page 21.

(8) Alberto Bartolomé Arraiza, Alfombras Españolas, MNAD, page 21-22.

(9) Rosamond E. Mack, Bazaar to Piazza, page 78

(10) John Mills, carpets in Paintings, 1983, pages 11-14.

(11) John Mills, carpets in Paintings, 1983, pages 15-18.

(12) Il-Khanid: Mongol dynasty ruling greater Persia between 1256 and 1335, reporting to the Great Khan.

(*)

Many thanks to Patricia Jansma who suggested buying Onno

Ydema’s outstanding «Carpets and their dating in Netherlandish

paintings»

Part 1: Animal Rugs in Renaissance Paintings

Part 3: A Tale of Three Renaissance Ruggies

Part 4: Rugs in Sixteenth- and Seventeenth Century English Paintings