The Salon du Tapis d'Orient is a moderated discussion group in the manner of the 19th century salon devoted to oriental rugs and textiles and all aspects of their appreciation. Please include your full name and e-mail address in your posting.

Rugs and Old Masters: Part 3 - A Tale of Three Renaissance Ruggies

by Pierre Galafassi

Surely, fewer than one per cent of all Renaissance paintings include a rug. In most of these few cases, carpets can be seen under the feet of a "virgin with child enthroned". Most painters never featured any rugs in their canvas and most of the few masters who represented a rug only did so once or twice, probably bowing to the request of a patron keen to show off a status symbol.

Three renaissance painters, among the most famous, are exceptional in that they used rugs quite frequently and often gave them an important role in their paintings. One could name them the first true Ruggies, surely deserving the veneration of all Turkotekers.

Hans Memling, Lorenzo Lotto and Hans Holbein the younger meticulously painted dozens of rugs and there can be hardly any doubt that they were attracted to this form of art. While they were certainly genuine Ruggies, it is highly unlikely that they could have afforded to collect carpets and owned the splendid pieces featured in their paintings. Lotto is the only one documented as having owned a "turkish" table rug, probably of limited value, since he pawned it in January 1548 for a modest sum.(1). It was perhaps one of these basic pile rugs which decorated windowsills during festivals in rich city-states like Venice or Florence

FIG 71. V. Carpaccio. 1495. Cycle of St Ursula. Departure of the pilgrims, detail . Accademia. Venice

In the period considered, top quality rugs were horrendously expensive and surely out of reach for a painter, be it even a famous one. Only very rich aficionados, rulers, the church and the political- or merchant elites of a handful of rich cities (Venice, Bruges, etc. ), could have afforded to collect them (2). People like Cardinal Thomas Wolsey (Chancellor of Henry VIII), the Florence rulers Cosimo and Lorenzo de’ Medici, the wealthy Venetian merchants Correr and Badoer, Cardinal Francesco Gonzagua or Robert Dudley, favorite of Elizabeth I, are among those mentioned as important collectors by historians.

A few examples demonstrate and in part explain the high comparative cost of rugs. Lorenzo de’ Medici’s inventory of 1492 lists 13 oriental carpets kept in a chest in the antechamber of his bedroom; their values ranged from 10 to 70 florins. The same inventory listed a bronze statue (50 florins) and a marble statue (20 florins) both by Donatello and six panels painted by P. Uccello, including the famous "Battle of San Romano" (on average, 50 florins each). Thus, these carpets were worth about as much as works of major sculptors or painters of Lorenzo’s court (3)! Sixty rugs shipped by Venice as a bribe to Cardinal Wolsey in 1520 were worth more than 1000 venetian ducats (4) or 3.56 kg of gold (5).

The high price of rugs was in part justified by the cost of some natural dyes like cochineal or indigo. Around 1436-1440 for example, 1 kg of the cheapest quality of cochineal (from Armenia, shipped via Trebizond) cost about 5% of the price of a slave. Based on notes of Venetian merchant Giacomo Badoer, Dr. Cardon (6) mentions an estimate of the price of one of Badoer’s shipments: a total of about 1300 kg of cochineal was worth about 9.7 kg of gold (half a million USD at today's price of gold). Not surprisingly these very valuable carpets were only shown at special occasions by most of their owners. In Venice, the rug capital of the west, some owners rented rugs for special occasions at a stiff price and against serious guaranties (7), and there was a secondhand market for worn pieces. Even in the palace of a very wealthy person, the floor was not covered with precious carpets at that time, but rather with reed mats, perhaps imported from Morocco (8, 9). These can be seen in many paintings until the seventeenth century; for example in FIG 72 and 73.

FIG 72. L. Teerlinc. 1570-1575. Queen Elizabeth and the Dutch ambassadors. Kassel

Quite surprisingly, very few (if any) of the most famous rug collectors of the time have been represented in a painting with one of their rugs or with any of their other treasures. Apparently, only the church and more moderately wealthy people were keen to impose, as a status symbol, the presence of their rug in the paintings they commissioned.

Hans Memling is the first of our three Ruggies.

Born in Germany around 1440, he may have been an apprentice in Rogier van der Weyden’s (11) workshop before moving to Bruges in 1465, where he lived until his death in 1494. During the second half of the fifteenth century, Bruges was a very active merchant-industrial-banking city, second only to Venice in wealth. Unlike Lotto and Holbein, Memling was well to do and owned a large house toward the end of his life. He is also recorded as having participated (with a modest sum) to Bruges’ lending of money to Maximilian of Austria. Since 1474 he had been a member of a confraternity of the city's social elite and was one of the 150 wealthiest citizens of Bruges. It cannot be excluded, therefore, that Memling owned a top quality rug or two himself. But it seems more likely that he persuaded his patrons and sitters, mainly the regents of the Saint John Hospital and the merchant elite, to lend their rugs to him. Among rug collectors, he is famous for having given his name to the "Memling gul", even though he was not the first painter to illustrate this motif. The work of an earlier "inventor" is shown in FIG 73. This illustration of a "book of hours" belonging to the Duke René d’Anjou, is not only arguably the first representation of the Memling gul, it also shows a rare instance of a rug used on the floor, and because there is a (far more frequently seen) reed mat under the rug.

FIG 73. B. d'Eyck. Livre du Coeur d'Amours Espris, detail. 1460. Vienna.

Although he was not the first to paint the famous "gul", Hans Memling featured many different versions in great detail.

FIG 74. H. Memling. Donne Triptych, detail. 1475. National Gallery. London.

FIG 75. H. Memling. Virgin and Child. 1485. Detail. Vienna

FIG 76. H. Memling. Virgin & Child. 1488. Louvre. Paris.

FIG 77. H. Memling. Flowers still-life, detail. 1490. Thyssen-Bornemisza. Madrid

The question of the origin of the Memling gul still has not been elucidated. Unless I err, the oldest extant rugs featuring it are attributed to Anatolia and dated from the fifteenth- (FIG 78) and sixteenth century (FIG 79). It also occurs on a large number of more recent Anatolian carpets.

FIG 78. Anatolia. Fragment with Memling gul . XV. O. Aslanapa. One Thousand Years of Turkish Carpets

FIG 79. Anatolia. Fragment with Memling

gul. XV-XVI. H. Kirchheim. Orient Stars

The Memling gul is also found on several of the oldest extant Caucasus carpets, dated from the eighteenth century, mainly on so-called Kazaks and Moghans. According to Dimand (12) a "scorpion" motif similar to the one in the red border of the rug in FIG 74 is characteristic of rugs woven in Spain, which could indicate that the Memling gul was also familiar to Mudéjar weavers. I am not aware of any extant Spanish Memling gul rugs, although I think the Memling gul was a very ancient and widely diffused motif. John Howe has recently done an outstanding presentation about the Memling gul at a Textile Museum "Textile Appreciation" session (13).

Another of Memling’s favorite rug motives was the so-called "large Holbein" pattern, of which he painted various sub-types (FIG 80 and 81). Interestingly, most rugs of this type in Memling's canvasses show a clear and saturated yellow, either in the field or in the main motif. This shade is also prominent in FIG 74 and 75. Such a dominance of saturated yellow shades is not encountered in extant carpets or in those in paintings. One can suppose that the rugs used by the painter shared a common, but unknown origin. Spain (14) and Anatolia seem to be the most likely candidates.

FIG 80. H. Memling. St John’s Altarpiece, detail. 1474-1479. Bruges

FIG 81. H. Memling. Virgin and Child. 1490. Royal Chapel. Granada

As shown in FIG 82-84 the dominance of a saturated yellow shade was not only associated with a particular field motif, but was quite general. From the about 17 rugs featured in Memling’s paintings, 14 (82%) show this primacy of yellow. I am not aware of any satisfactory explanation for this peculiarity. Did Memling select these rugs from his patron’s collections according to his own taste? Was the dominance of these yellow rugs a fashion among the elite of Bruges? Was it due to the privileged commercial relations of Bruges with a particular rug-weaving region? (14) One can note that a younger colleague from Bruges, Gerard David, in his famous 1495 "Sedano Triptych" (FIG 66 in a previous salon) also featured a carpet with a yellow field that was similar to the Memling’s shown in FIG 80 and 81.

FIG 82. H. Memling. Virgin enthroned with angels, detail.1480. Uffizi. Florence

FIG 83. H. Memling. Virgin and Child.1480-1490. Lisbon

FIG 84. H. Memling. Virgin and Child with St George, detail. 476-1480. National Gallery, London

Our second Ruggie is Lorenzo Lotto (1480-1556).

Born in Venice and perhaps trained in the workshops of Giovanni Bellini or Alvise Vivarini, Lotto lived an unsettled and provincial life. Despite his talent, he never met commercial success. His attempts to make a living with his painting in Venice failed, probably because his style was considered outmoded compared to Titian’s manierism, which was all the rage among the local elite. Lotto worked in Treviso, Rome and especially in Bergamo and in the Marches (Recanati, Jesi). He was rather poor all his life. He did not even mention his closest relatives in his testament, because he thought that they "would have no need for his modest belongings". Despite his lack of money, he did own one rug, probably basic or worn, which he pawned in 1548 for a modest sum in order to help a friend. His unusually frequent use of superb rugs in his paintings is best explained by a genuine passion for them.

In his early paintings (FIG 85, 86, 87, 88), Lotto represented Anatolian rugs featuring the so-called "re-entrant" or "Bellini" motif in detail. A fifteenth century example is in the Berlin Museum. Anatolian weavers used the Bellini motif until at least the eighteenth century.

FIG 85. L. Lotto. Virgin and Child. Altar piece. 1505. Santa Cristina al Tiverone Church. Quinto di Treviso

FIG 86. L. Lotto. Virgin and Child, detail. 1521. Santo Spirito Church. Bergamo

FIG 87. L. Lotto. Husband and wife, detail. 1523. Hermitage. St Petersburg

FIG 88. L. Lotto. Mystical marriage of St Catherine, detail. 1523. Bergamo

This last painting (FIG 88) was made as a payment to his landlord (the sitter on the left), who probably owned the rug. Perhaps to flatter the gentleman’s ego, Lotto painted the rug again on the right hand side of the canvas, but upside down. This was probably done to make it less obvious that it was the same rug. It must have taken some time after that work until he could find another wealthy sitter willing to show off his status symbol. FIG 89 and 90 are two examples of the rug motif to which Lotto gave his name. FIG 89 also features a couple of so-called para-Mamluk rugs.

FIG 89. L. Lotto. The Alms at St Anthony, detail. 1542. Saints Giovanni and Paolo Church, Venice

FIG 90. L. Lotto. G. Della Volta with his wife and children, detail. 1547. National Gallery, London

The "Lotto rug" remained popular among painters for more than a century, and was the most frequently represented geometric style rug in seventeenth century Dutch painting (15).

Lorenzo Lotto was not the first to show a rug with the "Lotto motif". Gregorio Lopes, a Portuguese painter, won that race by a whisker, featuring the motif in his "Salome", painted during his stay at Tomar (1538-1539) and also at some time between 1525 and 1540, in his "Annunciation", of the monastery of Santos o Novos, Lisbon.

FIG 91. G. Lopes. Salome, detail. 1538-1539. San Juan Bautista Church. Tomar. Portugal

Hans Holbein the younger (1497-1543) is our third Grand Ruggie.

Son of an Augsburg (Germany) painter, from whom he probably got his artist’s education. He left Augsburg for Basle in 1515, working mainly as a book illustrator. Portraits of the mayor Jakob Meyer and his wife, characterized by an amazing maturity and workmanship, are attributed to Holbein as early as 1516. In 1527, one of his paintings prominently featured a rug (tapestry?) (16) carrying the arms of a high Basle official as well as his wife’s (FIG 92). Shortly thereafter he painted the famous "Darmstadt Madonna" (FIG 93) in which his main patrons (together with Erasmus), Meyer and his wife, were represented kneeling at the feet of the Virgin and Child, on a splendid rug of a type now known as "large pattern Holbein".

FIG 92. H. Holbein the Younger. The Solothurn Madonna, detail. 1522. Solothurn. Switzerland

FIG 93. Holbein the Younger. Darmstadt Madonna, detail.1528. Darmstadt. Germany

Tired of making portraits of Jacob Meyer or Erasmus in all positions except upside down, probably weary of the lack of opportunities provided to artists by the austere Reformation and of the conflicts flaring up in this part of the world, he moved to England in 1527-1528 with Erasmus’ letters of introduction to his friend Thomas More (soon-to-be named Lord Chancellor). He immediately found high-ranking and rich patrons like More, William Warham, Archbishop of Canterbury and the rich merchant, Gisze. Thomas More’s disgrace and execution in 1535 did not hurt Holbein’s career; Henry VIII was among his patrons and regular sitters. Many of his English paintings featured rugs. While Holbein was not the first in England to use rugs in his canvasses, there can hardly be any doubt that he was instrumental in triggering a fashion that faded only a century later. His famous portrait of Henry VIII standing on a superb rug with mighty pose (FIG 97) was certainly the most often copied painting of the sixteenth and seventeenth century. Several of Holbein’s lost paintings are known to us only through the many copies made by English painters.

Another person probably was a partly unintentional, but important contributor to the great popularity of rugs among the English elite: Cardinal Thomas Wolsey. Wolsey (1472-1530) was Lord Chancellor of England. The greatest rug collector of the time, he accumulated about 500 carpets in his Hampton Court Palace. Venice is known to have provided 60 pieces, valued 1000 ducats (4) as a "gift" to the all-mighty Chancellor. When his failure to secure a divorce between Henri VIII and Catherine of Aragon led to Wolsey’s disgrace, he "donated" most of his belongings, including Hampton Court Palace and his rugs, to Henri VIII. Indeed, the King’s inventory of 1547 still lists over 400 pieces (17). Wolsey shocked his contemporaries by even walking on his precious rugs instead of storing them in chests most of the time. It is likely that Wolsey had imitators on a smaller scale among grandees of the Tudor court (17), that the King distributed some of the rugs inherited from Wolsey to familiars, as his son Edward did later (18), and that Holbein was authorized to use some royal carpets in his work.

FIG 94. H. Holbein the younger. William Warham, Archbishop of Canterbury. 1528. Louvre. Paris

FIG 95. H. Holbein. Portrait of G. Gisze, detail . 1532. Berlin

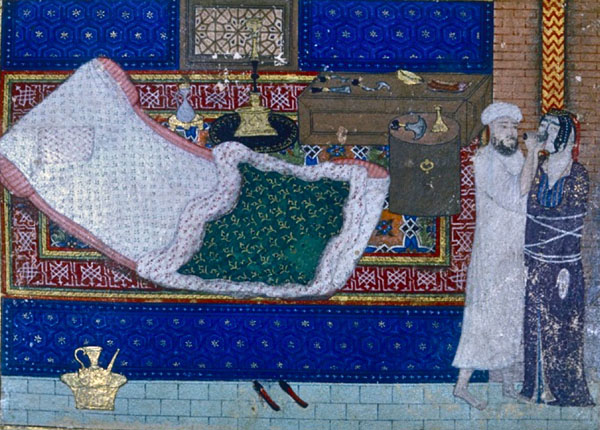

FIG 95 includes a table rug with small pattern Holbein motif and kufic border. This association is quite frequent and, as shown in many fourteenth- and fifteenth century Persian miniatures (19) (FIG 96), it was a standard for Persian weavers. Although extant small pattern Holbein fields with kufic borders are generally attributed to Anatolia, the motifs may have originated east of Anatolia, somewhere in north-western Iran for example, and moved west later, perhaps in one of the forced transfers of artisans that took place after the victories of the Ottomans over the Safavid Shahs (20). FIG 94 and 97 show two large pattern Holbein rugs. The latter includes two French ambassadors. It seems likely that the painting was commissioned by Henry VIII as part of his efforts to secure an alliance with François I, King of France, and that the splendid rug came from the stock inherited from Cardinal Wolsey.

FIG 96. Chubanid period. 1370-1375. Tabriz school. The cobbler cuts the nose of the barber’s wife. Topkapi. Istanbul

FIG 97.1 and 97.2. Holbein the younger. Portrait of the Ambassadors. 1533. National Gallery. London

Following The Ambassadors, Holbein painted several portraits of Henry VIII. The first (FIG 98) impressed the courtesans so much that they commissioned many copies during the next seventy years. All but one include rugs, sometimes different from the original. Although Holbein had no responsibility for these mostly posthumous copies, the rugs in them are interesting and the reader might appreciate seeing some of them, too (FIG 99, 100,101). The originals of two other Holbein paintings featuring Henry and his family are lost and known only by inferior copies, (FIG 102 and 103). A third (FIG 104) exists in two versions with two different rugs. Again, it seems probable to me that the King was lobbied into allowing Holbein-the-Ruggie to select studio props from Henry’s huge collection. Perhaps the same thing happened when, after Holbein’s return to Basle and his untimely death, various English painters were commissioned to make copies of his paintings.

FIG 98. Holbein the younger. Portrait of Henry VIII. 1537. Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool

FIG 99. Unknown painter, after Holbein. Henry VIII, detail. 1537-1557. Petworth House

FIG 100. Unknown painter, after Holbein. Henry VIII, detail. 1560-1570. Parham House

FIG 101. Unknown painter after Holbein. Henry VIII, detail. 1600-1610. Weiss Gallery

FIG 102. Unknown painter after Holbein. Henry VIII and his Family, detail. 1600-1621 Whitehall Palace.

FIG 103. Unknown artist after Holbein. The Family of Henry VIII, detail. 1543-1547. Hampton Court Palace

FIG 104. Holbein the Younger. Henry VIII and the Barber Surgeons, detail. 1540. London

In the next essay we will examine the century-long legacy of Holbein’s passion for rugs in English portraits and mention, in particular, another fanatical Ruggie, the painter William Larkin.

Notes: