The Salon du Tapis d'Orient is a moderated discussion group in the manner of the 19th century salon devoted to oriental rugs and textiles and all aspects of their appreciation. Please include your full name and e-mail address in your posting.

The Turkmen Asmalyk and the Chilkat Dancing Blanket

(Part 3)

by R. John Howe

Chilkat dancing blankets have a fairly restricted color palette. Black, white and yellow are frequent.

Sometimes there is the use of a yellow-green or a blue-green.

Only very occasionally is red encountered.

A much wider range of color use has been documented in Turkmen weavings. Some Salors exhibit as many as 15 colors. But the more usual number of colors in Turkmen weavings is perhaps five to eight and while I have not counted asmalyk colors closely, I think, because their designs often accentuate the graphic, that most Turkmen asmalyks also tend to have this smaller range of color.

The Chilkat seem, though, to have a much more specific set of rules concerning color use on their dancing blankets than do the Turkmen with regard to colors on asmalyks. Here are some of the seeming Chilkat color use rules:

All primary formlines are black.

The iris, or inner ovoid, within the eyelid, is always black.

In face shapes, the eyebrows, eyes, nose and lips are always black. The teeth

are always white.

All resultant forms are white.

All small perfect circles, except those found within the eyelid of a face are

white.

The S shapes found at the base of some U shapes are always white.

Whenever a small U shape falls within a “salmon-trouts head,” it

is always blue.

The mouths of headlike shapes are always blue.

Squared L and U shapes are usually blue.

Blue shapes never surround other blue shapes.

Blue shapes do not usually lie next to each other, even if separated by a black

primary formline.

The sockets of the eyes and joints are always yellow.

These rules governing color are sufficiently explicit that the wooden pattern boards (of which more below) that serve as close cartoons to guide the weavers of Chilkat dancing blankets, are done only in black and white, since the weavers “know” which area should be colored and in what ways. The Turkmen, aside from the great preponderance of red fields in their weavings, do not seem to have comparable rules governing color use.

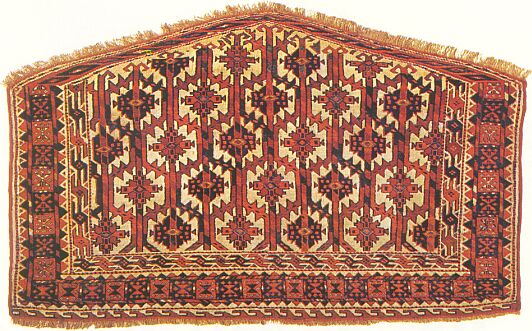

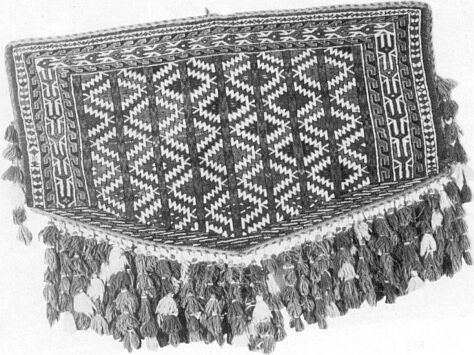

Designs in both the Turkman asmalyk and the Chilkat dancing blanket seem often to have originated in nature, but have, in both instances, undergone abstraction, albeit of very different sorts. One of the most frequent Turkmen asmalyk field designs resembles a series of drooping plant-like branches, say, like a pine tree.

Another frequent Turkmen asmalyk field design resembles a series of abstracted flower heads.

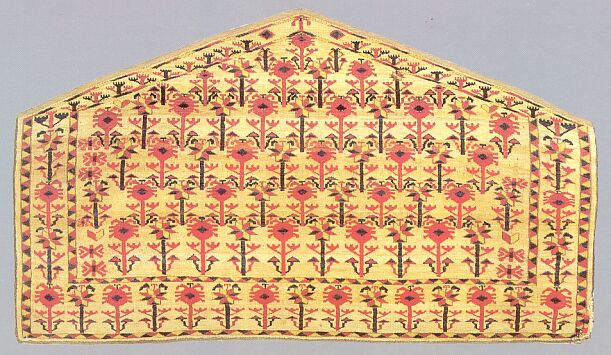

Here’s another of this same sort.

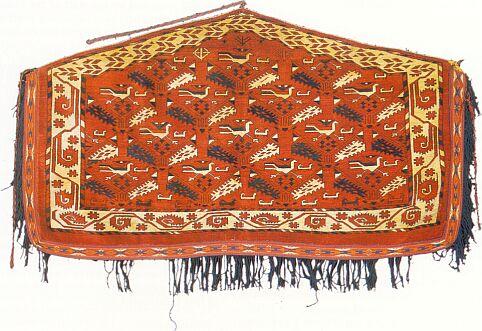

This famous asmalyk design includes plant forms, birds and small animal forms.

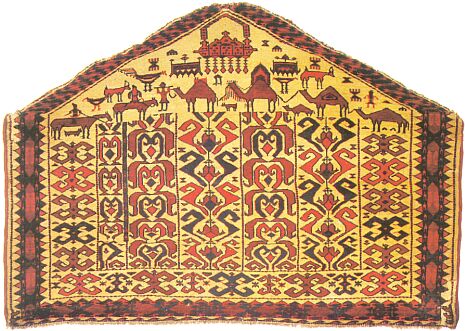

And while Turkmen designs might also seem frequently to have devices that are simply geometric, some asmalyks contain fairly realistic representations of people, animals and of Turkmen jewelry.

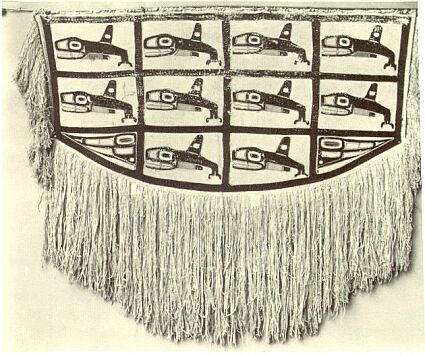

The Chilkat dancing blanket designs seem to have been derived almost entirely from forms in nature. There does not seem to be, in Chilkat design, excepting for the very early period referred to above, much that can be described as purely geometric. Some early ones, the designs of which the scholars classify as “Configurative,” are quite realistic. There is abstraction but it has not yet distorted the “natural anatomical form…” seriously. “It is still possible to identify the creature.” This one is described as “Killer Whale.”

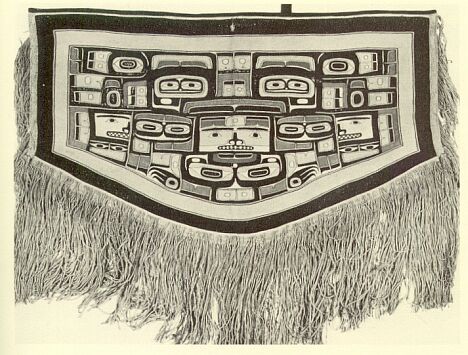

But far more serious abstraction is a major characteristic of Chilkat dancing blanket designs. The first move of abstraction was to “fill the entire available space,” in the blanket. The parts of the animal are arranged to fill the design field regardless of their anatomical relationships.

One of the abstracting Chilkat moves to fill space, was to divide the creature down the middle and to disperse the parts: two mouths, etc. The scholars call this sort of abstraction “Distributive.”

Because Chilkat dancing blankets came to be woven in three sections, a middle and two side panels a further move of design abstraction was made, that of “Paneled Distribution.” The design field itself in this category is divided into three distinct panels…White lines emphasize the divisions. Within these panels the designs are distributive.

The designs of the distributive sort are open to lots of interpretation. “They are ambiguous” and “Their meanings are hidden in the minds of their creators.” Some, though, claim that close study of these designs permits one to identify the “forms that define the creature.” This is what the term “formline” design refers to. But the experts often disagree seriously about what animal (frequently a fish) the form lines indicate a given design represents.

Here is the link to a web site that provides some additional discussion of such design characteristics and issues.

One last thing to note about the designs on Chilkat: they are symmetrical. The right half of a given blanket design, or if a paneled design, of each design panel, is simply reflected in the left half. This will be important for another design practice that we will treat in a moment.

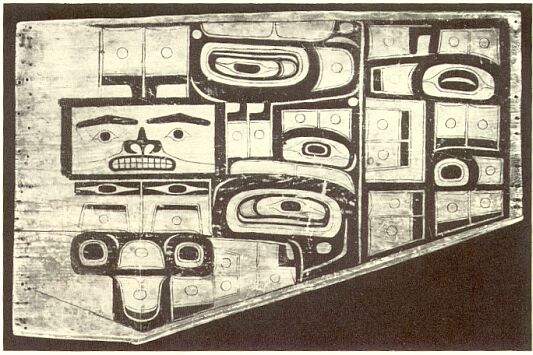

The Turkmen women who wove the asmalyks did so usually within a framework of tribal tradition that included a range of designs that were seen as appropriate. Within this range, but also seemingly sometimes in violation of it, the Turkmen woman seems to have been relatively free to choose her design for the asmalyk she was weaving. Turkmen tribal weaving seems to have been largely from memory regardless of the design(s) used. Chilkat practice is distinctive here in several respects. First, it is the Chilkat men who draw the designs to be woven on the Chilkat blankets. They specify the designs to be used in full scale by painting them on pattern boards.

These pattern boards show only a little more that half of the design to be woven in a Chilkat dancing blanket. A little more than half, because usually there is a “face” design in the center of the such a blanket design and all of it is often included on the pattern board. But in general the pattern board includes only the design to be used on one vertical half of the dancing blanket and the weaver was expected to weave this same design in a reflected mode on the other side.

Pattern boards were drawn in black only. Chilkat dancing blanket designs are woven on a white background, so there was no ambiguity about which areas were to be black. White areas on a Chilkat dancing blanket would usually be white, but would also sometimes be woven in another color, as we have seen above. The absence of guidance about these other colors on the pattern board, especially given that they prescribe very literally in other regards, how the design was to be woven, suggests how strong the conventions were concerning the use of other colors in Chilkat dancing blanket designs.

They did not need to be specified. The weaver would “know.”

There seems nothing parallel in the case of the Turkmen asmalyk to this division of labor between men and women in the creation of the designs in Chilkat dancing blankets. We conclude that the social rules that produce the designs on the Chilkat blanket are distinctive from those that govern those on the Turkmen asmalyk.

As I worked with this salon essay it seemed to me that despite their similar shape and size, that the Chilkat dancing blanket and the Turkmen asmalyk turn out to be quite disparate textiles, that developed at a great distance from one another and whose similarities are largely the result of chance. That there is no very obvious evidence suggesting that they might be related. More, since both weft twining and pile weaving are not greatly restrictive methods, it does not seem that the similarities are at all the driven by technical factors.

But as I was writing this salon essay, I chanced into an internet conversation with Michael Craycraft, who cautioned me not to assume that these shapes came to be as they are entirely without being related. He pointed out that the folks who settled in Alaska, came long ago from Asia and may have come from a part of it not far from that in which the Turkmen originated. I looked about a bit to see what the migration patterns seemed to be and found some web sites that suggest what research says about the possibilities here. http://www.clovisandbeyond.org/articles1.html; http://land.sfo.ru/eng/7_6.htm; http://www.ucalgary.ca/applied_history/tutor/firstnations/theories.html; http://www.fsc.edu/socsci/savant/BERINGIA/BERPPR.HTM; http://www.akgenweb.org/.

You can see that Michael’s suggestion has some support.

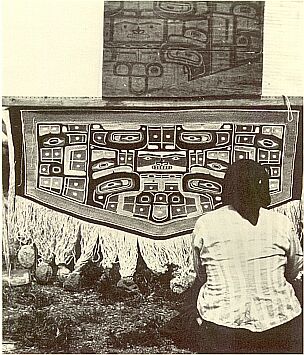

And, of course, we should remember that life is not neat. Often just when you think that you’ve figured something out, and have rightly concluded that the Chilkat dancing blankets are entirely disparate from Turkmen asmalyks, and despite the established fact that auction catalogs often get things wrong, you find yourself leafing through something and come onto an image like this.

![]()

You now know a great deal more than you may have recently about the Chilkat dancing blanket and how it compares with the Turkmen asmalyk. You may, in fact, now know more than you actually wanted to about this subject. But it seemed an interesting comparison to me when I first encountered it and it has been interesting to explore a bit more in this salon essay.

OK, what might we talk about in this salon discussion? I would not bar anything that seemed relevant to this comparison or to thoughts about either of these textiles, but here are some possibilities.

It may be that others will have additional things to say about the Chilkat dancing blanket or about related textiles (vests and leggings were also made). For example, what impact do we think, if any, the indication that the wool in Chilkat blankets is from dead goats, has on our usual evaluation that rugs made with the wool of dead sheep are beneath consideration?

It may also be that there are interesting and useful things to say about weft twining, a very ancient technique used worldwide.

Or some may want to talk a bit about the Turkmen asmalyk. We have talked about some aspects of it back in Salon 37: Turkmen Pentagonal Weavings. by Steve Price.

There may be things that are triggered by this salon essay or its subject that I cannot anticipate. Regardless, I invite your most vigorous contributions to this salon discussion.

Regards,

R. John Howe

Here is a link to a listing of the sources I consulted and used while writing this salon essay. I have quote mostly from the Samuel book.