The Salon du Tapis d'Orient is a moderated discussion group in the manner of the 19th century salon devoted to oriental rugs and textiles and all aspects of their appreciation. Please include your full name and e-mail address in your posting.

The Turkmen Asmalyk and the

Chilkat Dancing Blanket

(Part 2)

by R. John Howe

The Turkmen were mostly sheep herders and horse breeders. Some did a little farming and a few, close to the Caspian, apparently even fished a little (I met a young Yomut-Tekke woman at the Smithsonian Folklife Festival last year who said that her family lived near the Caspian and that her father was in the Caspian coast guard). Many Turkmen were nomads and followed the grass, although their usual migrations were apparently fairly short.

The NW Indians who wove the Chilkat dancing blankets were subsistence types, hunter/gatherers in an area rich in natural resources. The area of Alaska in which they lived is a rain forest lush with cedar trees and close to protected seas. They lived in plank houses in the winter, but moved to hunting, and especially to fishing grounds in the summer months. Nature was so good to them that surpluses could be accumulated with all the usual results. They developed a set of hereditary classes (nobles, ordinary folks and slaves) differentiated by wealth. Slaves were owned by the chiefs. They were war captives who were first offered to their own tribes for a ransom. Those not ransomed and their offspring became hereditary slaves.

These NW American Indians also had highly developed crafts, of which weaving was just one (e.g., they made sea-going canoes, totem poles and basketry) and developed traditions and ceremonies of which the potlatch meeting was perhaps the most important, at which gift-giving was central. One was honored by being given a gift, but the giver obtained even more honor by demonstrating an ability to give away valuable things. The Chilkat dancing blanket was an item of high value and was one of the prized gifts at potlatches. And if a dancing blanket was available to be given, but no one person was deserving enough to have it all, it was sometimes cut into strips and the strips were distributed to different honorees. Such strips were also valued and collected and sometimes sewn onto a garment worn at potlatches. So it appears that these NW Indians were not averse to collecting fragments.

There were also wealthy Turkmen and headman positions seem also to have been passed through inheritance. But the chief social distinction among Turkmen was with regard to those who could indulge in the nomadic way of life and those who were forced into settled living. The rather loose and independent family-yurt-based organization of Turkmen society pressed against tendencies toward hierarchy. And while wealth could be assembled, the harsh character of the area in which the Turkmen lived constantly exposed what one had accumulated to loss. The Turkmen also took slaves in their raids but did not, I think, have hereditary classes of slaves as these NW American Indians seem to have had.

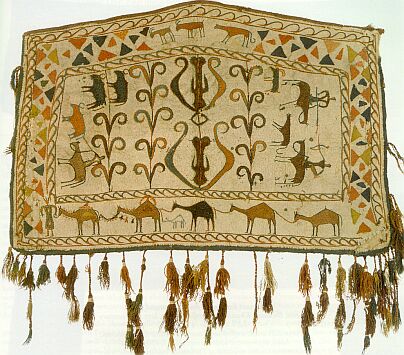

Most asmalyks were wool pile weavings, although embroidered examples also were made.

And some of embroidered ones were done on a felt ground.

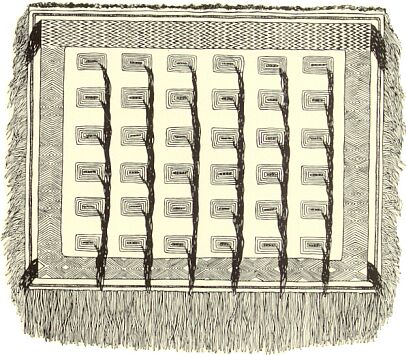

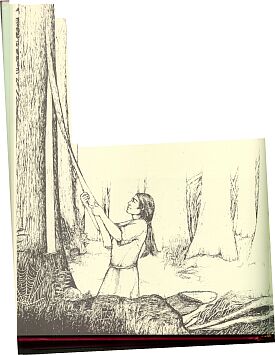

The Chilkat dancing blanket is distinctive both with regard to materials and to the techniques with which they were/are woven. There is evidence that the earliest dancing blankets (no examples survive) were woven entirely with wool. Here is a pen and ink reconstruction of one by the American Museum of Natural History.

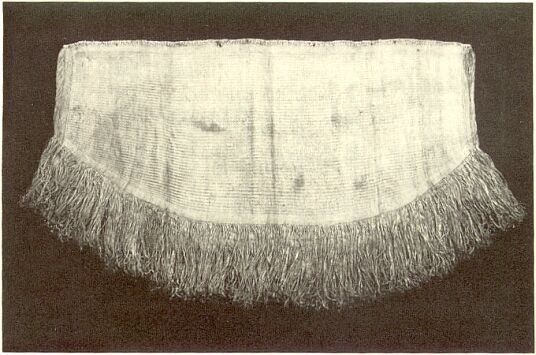

And at the time of Cook’s voyages into this area (the late 1700s), some examples of such robes were collected that are woven entirely of cedar bark.

And there is one example known in which the wool warps are interspersed with fine strips of otter skin (skin side up on the design surface). But the most usual practice has been to use warps on the Chilkat dancing blanket that are fine strips of cedar wood wrapped with white mountain goat hair. “It seems highly likely that the classic Dancing Blanket grew out of two traditions: the cedar bark robes of the south and the geometric chief’s robes of the north.” Here is a transitional piece, with warps of cedar and wool, collected during Cook’s third voyage. It shows areas of the earlier “geometric” patterning but also, what became to be called “formline” designs. This latter term refers to the black lines in Chilkat designs that ostensibly suggest the animal forms in them.

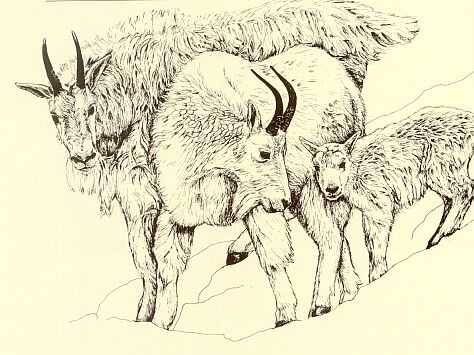

The wool used in pile Turkmen asmalyks is sheared from domesticated sheep. The wool used in Chilkat dancing blankets is from wild white goats that inhabit the high mountains only short distances inland in this part of Alaska.

One of the distinctive features of the Chilkat dancing blankets is that the wool on them is harvested from dead goats. The mountain goats from which this wool came were wild and had not been domesticated. So the wool could only be obtained by killing the animal. The processes by which this goat’s wool was obtained had roles for both men and women, something else that seems distinctive about the creation of the dancing blankets. Here is a longish quote from Samuel, describing how this wool is obtained:

“It was the work of the men to provide the goat skins from which the women would remove the wool. The skins were taken from the animal and, if not used immediately, were hung to dry in the open air. When it came time to remove the fleece, the woman would first spread the skin before her and sprinkle it with a soft, white powdered clay. This clay was obtained from deposits in the ground, molded into rounded balls twelve to sixteen centimeters in diameter, and baked in a fire until dry. The balls were then powdered and beaten into the fleece with a long flat stick until much of the dirt and oils had been removed and the wool looked snowy white. To remove the wool from the hide, the skin side was wetted and the hide side then rolled and left to set for several days. The roots of the fibers would loosen during this time so that the fleece would readily release from the hide. Sitting on the ground, the woman would take the skin across her knees and push the fleece from her, rolling it off the hide in large patches. These she would set aside in low, flat baskets, repeating the process until the entire fleece was free.

“The long, stiff guard hairs, if spun would produce a very coarse yarn. This was not desirable and therefore these hairs had to be eliminated. Having removed the fleece in large patches, the arrangement of fibers had not been disturbed and the woman could easily pull the hairs out of the wool. Some of the finer hairs might remain, but these would not affect the final product.

“…Once removed from the hide it did not have to be combed or carded in order to be spun, but simply was drawn out and rolled into roving and wound gently into balls. For safety and cleanliness, these roving balls were stored in round gut bags until spinning began. The fleece from three mountain goats was needed to produce the average Dancing Blanket.”

Spinning by Turkmen women of the wools used in asmalyks seems mostly to have been done using drop spindles. Some drop spindle worls have been found among the tools of the weavers of the Chilkat blankets, but their spinning of dancing blanket warps “was done between the spinner’s hand and her knee without the aid of a spindle.”

Woven textiles were likely first made from plant fibers and in this respect Chilkat dancing blankets retain echoes of this ancient practice. It is likely, because some early dancing blankets were entirely woven of cedar bark strips (cedar is very plentiful in the nearby rain forests) and because the oldest geometric patterned dancing blankets seem to have been made entirely of goat’s wool, that the merging of these two traditions included the merging of these two practices. Goat’s wool is used, but so are cedar bark strips. They are combined in the Chilkat blanket warps, with the cedar strips wrapped lightly by the goat ’s hair wool.

The harvesting and preparation of these cedar strips also deserves lengthy quotation.

“…Women collected the bark of the yellow cedar tree in early spring. When they went into the forest, they took with them a sharp knife for severing the bark and a rounded bone one for lifting it. With the sharp knife, a slit would be cut between twelve and eighteen centimeters in width near the base of a tree. Then, prying the bark loose with the flat, gentle blade of the bone knife, the woman pulled upward.

“The bark came away in a strip about three meters long, narrowing as it ran up the tree. The pungent yellow strips were then rolled up to be taken back to the village. The women never took too much bark from one tree, but moved from tree to tree to prevent serious damage. When enough bark was collected, the carried the strips back to the village and hung the strips inside the house. Once dry, the strips were tied in groups and hung inside the house to await further processing.

“The dried strips of cedar bark kept indefinitely if they did not get damp. They were stiff and hard, the inner side being a gold color, the outer a rich red brown. To work with them, a woman had to boil the strips for two or three days to remove resins. Boiled long enough, they split easily by bending the pliable ribbons of bark back and forth to loosen the layers.

Remnants of the reddish brown outer bark were removed by rubbing a thumbnail or bone scraper down the bark strip while it was quite wet. The bark could be separated in layers as thin as a leaf or as thick as a clamshell. The warp yarns of a dancing blanket needed strips as thin as blades of grass. When the women had separated the strips of yellow bark they were dried and tied in loose bundles.”

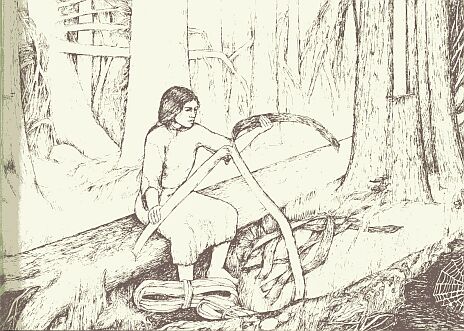

The spinning of the goats wool and the cedar bark strips was done against one’s leg and without resort to spindles (Chilkats did have and use drop spindles but only for weft wools). Very little goat hair is needed to cover the cedar bark warp strips. Here’s how this was done.

“A short length of mountain goat roving is pulled out until it is very thin and filmy and approximately one centimeter wide and sixty to one hundred centimeters long. A strand of cedar bark is wetted and laid in the center of this roving. The…wool adheres more readily to a wet strand of cedar than to a dry one and the dampness of the bark helps set the spin.

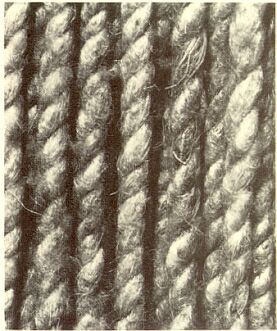

“In spinning two single strands are spun simultaneously, down the leg, and plied together” as the hand reverses and moves back up the leg. This seems like a very tricky operation, but the Chilkats could apparently do it well and with considerably regular results. Here are some spun warp yarns produced in this way.

Turkmen asmalyks were pile weavings. Pile weaving is a very non-restrictive technique. Despite its basic rectilinear grid of warp and weft, the fineness of most Turkmen textiles permits very flexible drawing. We do not see it much, but the Turkmen could resort to curvilinear designs. The technique of pile weaving did not restrict that seriously.

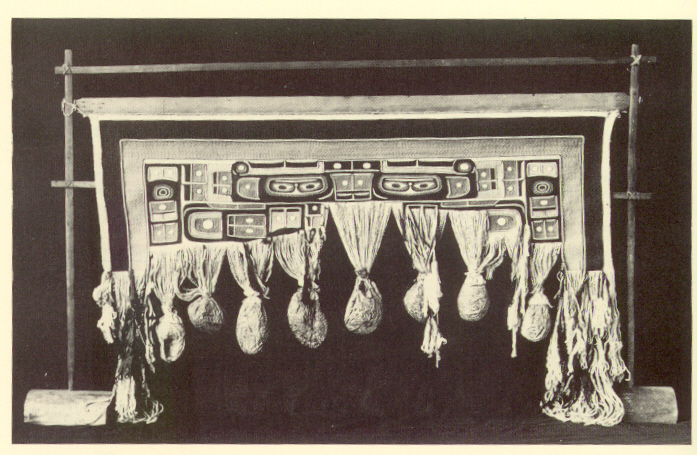

The Chilkat dancing blanket is made with weft twining, a very different technique, indeed. In fact, one which does not depend at all on many of the features of even the crude looms that the Turkmen used. The “looms” on which the Chilkat wove their dancing blankets are vertical but serve mostly simply to hold the warps at the top. The warps are not fastened at all at the bottom. At best they are “weighted” by their own length below.

The warp ends hung, gathered in bags made of animal gut to keep them clean.

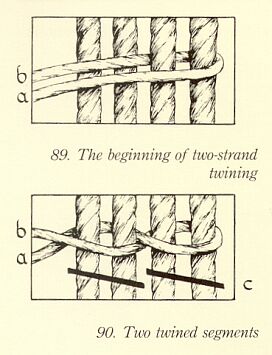

Weft twining is a matter of taking pairs of weft around opposite sides of one or more warps and then crossing them over one another on the far side of the warps encircled. The position of each warp thread is reversed in each move around the warp(s) as one moves across the weaving. There is no heddle on the loom nor is there in weft twining the equivalent of picks of straight weft that move from one side to the other over and under alternate warps. Some books call “weft twining,” “finger weaving.”

Weft twining, as used by the Chilkats, and although radically different from pile weaving, is also not a restrictive technique. Although weft twining is itself fairly flexible, since weft can be moved over one warp at a time, its flexibility is tied to variations in the distance the weft moves over the warp(s).

One of the great technical achievements of the Chilkats was their combination of some forms of braiding with weft twining that “freed their dependence on the warp as a base…they could travel at any angle over the surface of the weaving.

No longer restricted to elements which traveled only horizontally, the weavers could form the curvilinear shapes of the formline designs.” One instance of this is seen in their ability to draw perfect circles as in the “eyes” in such designs. So while the techniques used to produce the Turkmen asmalyk and the Chilkat dancing blanket are disparate, they are both flexible, and we cannot look to restrictive technique as a possible source for explaining their similarities.

This is the end of Part II of this initial salon essay. Please go on to Part 3.