by Horst Nitz

Summary

A

flat-woven rug unearthed by the author in the far southeast of Turkey

some time ago has been identified as to its origin with the Mountain

Nestorians in their former retreat area in the High Kurdish Taurus (1). The

central medallion of the rug bears an un-iconic, non-idolatrous

representation, a composite symbol of Jesus Christ that represents a

stylistic tradition as it has evolved in the early days of Oriental

Christianity. While the rug has not been C14-dated and the actual age

of the textile remains uncertain (2, 14), it appears to carry the key

to a new research area, i.e. the textile heritage of the

Church

of the East (3), the great missionary church of Asia during late

antiquity and European Middle Ages.

The author proposes that

early Nestorian Christians (4) were functional in the creative process

and in the distribution of textile patterns in Asia; that this took

place in the context of their missionary activities in the early

centuries of the new religion; and that this process is traceable in

the textile heritage of the nations that lay on their missionary path.

A

first reconnaissance focuses on the region between Mesopotamia and the

Caucasus, encompassing Anatolia east of the Euphrates and the

Roman-Persian border running roughly at 190° from the eastern shore of

the Black Sea, and Azerbaijan to the east. These areas had

traditionally been or had come under Persian suzerainty and Nestorian

influence in the first centuries AD. Also, the progress of the mission

in this region is fairly well documented, which provides a raw matrix

of the distribution path of a particular rug design and its

subsequent transformations.

Introduction

The discovery of the Pazyrky rug by S. I. Rudenko in a frozen tomb in the High Altai in 1949 left Kurt Erdmann in a dilemma. The prevailing concept with the rug world that he had formulated, of Turkish pastoral nomads as the originators, and their westward stride as the force behind the migration of pile rug designs and technique from Turkestan into Anatolia did not allow for an ancient pile rug showing up as far northeast as Siberia, and neither for one originating as far southwest as Asia minor and Azerbaijan as Rudenko suggested. To Erdmann, Turkestan was the cradle of pile carpets, and the Seljuk had introduced them into Muslim culture (5). He must have been aware of the Pazyryk rug’s potential to invalidate his theory. Apparently, without having seen the rug himself, in a somewhat winding statement he argues that the Pazyryk rug can be no pile rug, and that it must be a cut-loop fabric (Erdmann 1975, page 13). In spite of such inconsistencies and implicit fundamental errors in Erdmann’s theory it is still going strong with the rug world (6). If this is so for want of an alternative model of developmental rug history, there is good news. It centres on a rug design commonly known as the ‘Gashgai Göl’, which is not what the term suggests. In fact, it is a transformation of the probably oldest known complex rug design after the Pazyryk carpet, and its geographical origin may be very near to that of the most famous rug of all. This will be explained in more detail in the following chapters.

The literature on Caucasian Carpets is extensive (7). Generally, it seems agreed upon that the oldest rugs from the Caucasus region can be dated to the16th century and belong to one of the ‘classic’ groups, of which the ‘dragon’ carpets are probably most prominent (Opie 1992). However, it has also been argued that there may not be a clear enough distinction in every case between Caucasian Carpets and such from neighbouring Anatolia and NW-Iran, and that there may even exist some older Caucasian carpets that have been attributed to those neighbouring weaving cultures (Azadi, Kerimov and Zollinger 2001). In any event, this is about prime carpets made in workshop with a likely attachment to a local aristocratic court or similar. The situation with village carpets is quite different. Not only that they account for the far majority of rugs, they also are considerably younger, mostly dating from the 19th century. However, questions have arisen, whether the motifs in those ‘folk’ rugs may not be much older than the designs of the ‘courtly’ carpets (8). This question mark may be attached with equal justification to the neighbouring regions in Anatolia and in Iran, and it is going to guide us in the exploration there as well.

Almost thirty years after a rug reconnaissance tour by the author into the far south-east corner of Turkey, that at the time had been considered a failure, it had turned out to have unearthed a rug, which seems to be the key to the understanding of important early developments in the genre.

In the autumn of 1980 that tour came to a premature halt at a military post on the road from Van to Hakkari (9). Back in Van an opportunity arose to look at a number of old flatweaves attributed to an hitherto unheard Kurdish group, that of the Herki. According to local informants, the textiles had shortly before emerged in connection with a military operation on the frontier to Iran and Iraq, the target area of the intended survey. One of the pieces especially resisted all attempts of attribution within a Kurdish pattern catalogue (10).

Historic sources of the late 19th century relate that the assumed weavers of the rug, the nomadic Kurdish Herki, on their annual migration between summer (Turkey, Iran) and winter pastures (Iraq) regularly crossed Nestorian settlement areas and committed robberies and other acts of violence on the sedentary population (11). Since they were forced into a sedentary life by Turkish and Iranian authorities on their respective territories in the 1930s, they have been dwelling in the Turkish-Iranian-Iraqi triangle, the former settling area of the mountain Nestorians (12).

The textile is at hand. It is a tightly woven, carefully executed piece of work measuring 75 x 172 cm, is in a good condition and appears to be the left one of originally two flatwoven panels of the sumac type (13) that were stitched together along the middle. Warps and wefts consist of wool and goat hair. The age is uncertain (14). In colour scheme and style (general layout, secondary motifs, borders etc) it resembles a number of rugs dated to the 13th - 16th centuries in the keep of Istanbul museums Vakiflar and TIEM as well as other international collections (15).

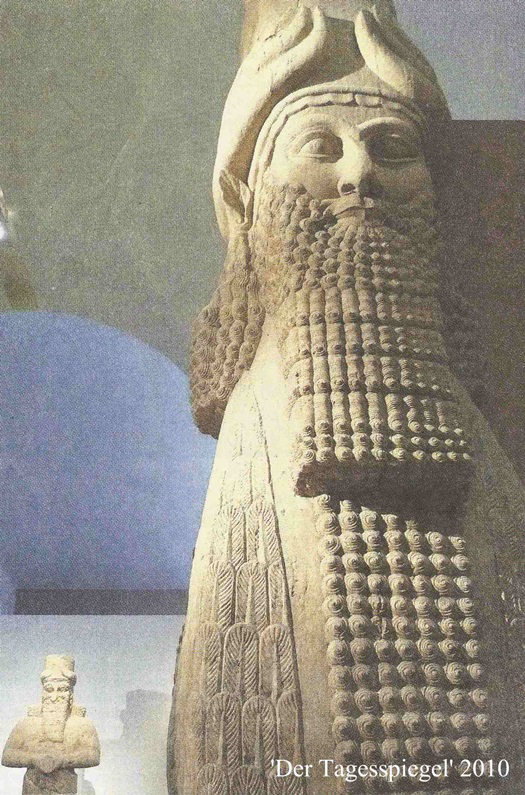

At a first glance the rug appears to be laden with symbolism of a complex and unaccustomed kind. This gives way to a sense of understanding once assessment is carried out within the cultural and historic context of Northern Mesopotamia and of the special Nestorian Christology and liturgy: the two natures of Christ; Mary as birth-giver but not mother of God as in other churches; Christ’s assumed true presence in the Lord’s supper ceremony etc.) all is represented in symbols. The complex representation of Jesus Christ on the white-grounded medallion (16) in the form of the construction rhombus of the 'vesica piscis' refers to the early Christian period and a late-antique period international style; also a marked old-testament influence is apparent, that has as yet not been unravelled in all aspects (17). Antithetic mighty horns as attributes of the divine make use of an ancient image language that places the rug firmly in a Mesopotamian tradition (18).

ComparisonsSuch references across church boundaries may be indicative of an early Christian international style with its roots going back to a time before the great schisms (also see endnote 11).

This may also be said of another element in the composite form, which has not been mentioned before, i.e. those dangerously looking angled jigsaw forms within the ‘vesica piscis’. They may contribute least to the importance of the overall symbol, but have taken longest to identify. For some time, it was considered that they are derivates of the Akkadian god Shamash’s emblem, the arc-shaped pruning saw. Shamas was also worshipped in Assur (19). He is also identifiable by the rays emitting from his shoulders, which is quite appropriate for a sun-god (Black & Green, 1992 p.182-184). The white field of the rhombus, the ‘vesica piscis’ was thought to express the same in an image language better adapted to the technical requirements of the medium carpet and as a result of a transformation process from an earlier cultural context into a later one. Maybe Christ has inherited the symbolic white colour of the sun at midday from Shamas together with the Mesopotamian type mighty horns as a symbol of divinity. However, the angled jigsaw forms may also represent a simplified palmette motif. In a more naturalistic form, such palmettes are flanking the figurative busts of saints in a chapel LIV fresco at Bawit / Egypt (Zibawi 2004; page 74). This may be another indication of the existence of an early Christian era international style. For the time being, the question has to be left unanswered, whether it is the palmette or the pruning-saw, and which one precedes which (if any).

The objects in the comparison discussed so far are more or less naturalistic interpretation of their respective theme, including the Talas valley plate from a Nestorian context. Where now can the composite symbol be positioned in relation to those and other major art works of the wider region, i.e. Dura-Europos (Synagogue, House Church) and Edessa / Urfa (Gospel of Rabban) on a scale of figurativeness vs. abstractness? The traditional classification rule - Christianity: images; Judaism and Islam: no images – has recently given way to a more flexible approach as it has been advocated by modern scholars. However, the Oriental Orthodox Churches i.e. Nestorianism have not been in the focus of this discussion – although they ‘play on the same grounds with Judaism and Islam’. Any answer to this question should address the social situation in the first few centuries of the Christian era as well. There were Jews that had turned to Christianity but maintained their old ways to varying degree; others had submitted to baptism and had given up Judaism altogether; further, there were the religiously homeless, outcasts of a Jewish society, deported tribes of captives, resettled populations, stranded soldiers etc. When these circumstances are taken into account, a broad spectrum of interpretations and practices of the Mosaic ban on images seems probable. The ‘You shall not make for yourself an idol’ offers some leeway that can be used or not: the representation of epic scenes or everyday events do not necessarily meet the criteria of idolism - or challenge them. The Jews of Dura-Europos on the fringe of one empire and within the reach of another, may have felt that they want to accept the challenge thrown at them by the Christians (who had just before decorated their church with frescos – more correctly, temperas) and show what they can do themselves. The amount of money that has gone into the project seems to speak for such an interpretation. How Jewish of a strict type were the Christian originators of the symbol of Christ that is being discussed and, were they the predecessors of those Mountain-Nestorians in the Hakkari region? For the first US missionaries to reach them in the 1830’ies, they were the ‘protestants of Asia’ because of a complete absence of images from their churches (Perkins, 1834; Grant 1835). Both authors address the question of descent, because they were impressed by the observation that the Nestorians can converse with the Jews in the region in a common language and that they follow religious practices, that are described in the old testament and that are unfamiliar to other Christians. The Nestorians, that Grant has lived among, described themselves as descendants of the Jews that were taken into Assyrian captivity (20). This could mean, that the Hakkari Nestorians may have been made up from the deported Jews that were settled in or near the mountains in Assyrian times and had adopted Christianity early, and later Christian refugees indigenous to the Assyrian plain who moved up into the shelter of the mountains in the 14th and 15th centuries, when under pursuit by Tamerlane’s army.

Expatriates often hang onto traditions of their old home country with verve, and foster conservative ideals. This may have been the case here, with a mixed fraction of Jewish descendants at the starting line of Christianity, that abode to the Mosaic law more fervently than their brethren at an intersection of major trade routes at the great border town of Dura-Europos, where rules may have been somewhat looser. Christians seem to have benefited as well in that they were tolerated and could practise their religion rather openly, whilst elsewhere in the Roman Empire – we are still writing the polytheistic era – they were persecuted.

The abstract nature of the composite symbol in the rug may also be due to a tradition even older than the Dura-Europos paintings, which are dated 235-244AD. A nomenclature offered by Baumer (2006) knows three phases within the orthodox community, (1) an emerging allegorical phase towards the end of the 2nd century, ‘in which animals and objects such as the lamb, the dove, the fish, the vine and the anchor referred to symbolically suggested figures. Then the first depictions of people appeared around the mid-third century in the catacombs, where Old and New Testament figures and the Good Shepherd could be seen on the walls. The murals of the Christian chapel of Dura-Europos date from the same period… At the beginning of the fourth century the depiction of Christ, the apostles and the saints began to become more widespread; but it remained controversial’ (p. 164-165). If going by Baumer’s nomenclature, it would be phase one for the rug.

Supporters of images like the early Cappadocian fathers thought that pictures might help to educate the ‘spiritually poor’ and referred to an invisible spiritual reality emanating and passing on from them (Baumer 2006; Döpmann 1991). If this goes for images, why not for symbols as well? It would have strongly recommended rugs for missionary work sic! Ease of handling and availability of materials to reproduce such woven symbols and multiply the message could be added to the list.

Concerning the function of the rug one may first of all think of the Lord’s Supper ceremony (Eucharist). To Eastern Christians the Eucharist is not just symbolic, it is the central part of the service to them, as they believe it truly becomes the real body and blood of Christ, and through their partaking of it, they see themselves as together becoming the Body of Christ, that is, the Church. In one of the liturgies used by the Mountain Nestorians, as Percey Badger observed, at the hight of the ceremony ‘the priest shall fold his hands upon his breast in the form of a cross, and shall kiss the centre and the two horns of the altar’ and by doing so physically wellcomes Christ to the assembly (Badger 1852, p. 234). In the absence of other two horns on or at the altar, this tells us where the rug has probably served (some of the lent cloths’ and altar blankets at Kloster Lüne in Northern Germany echo this usage in form and function).

However, rugs of this type may have had an additional function as a woven catechism, carried by monks and traders on their journeys to far-away and illiterate societies. The ‘facilitators’ may even have been illiterate themselves. Textile backed visualisations would have crossed language barriers easily, and teaching the technique how to do them should have been an effective prompt in opening hearts to the new religion - of the ‘spiritually poor’ on the missionary path beyond frontiers. Redrawn, expanded, simplified or otherwise processed in tune with the tides of history, in any case mostly unrecognised and somewhat ruffled, the central motif of the rug has survived and made or makes an appearance on textiles of a wide array of people from Anatolia to Central Asia (21).

If the rug had passed through the arts trade, it almost certainly would have been attributed a Qashqai rug from the Iranian south-west province of Fars, as has happened in a known instance (see plate 11). The symbol of Christ appears in a more or less digressed form and in many variations on rugs from that region. It is generally assumed in the rug literature, that the Qashgai Federation was founded on the order of Safavid ruler Shah Isma’il (Housego J, 1978) some time after the Persian defeat by the Ottomans at the battle of Chaldiran, or by Shah ‘Abbas. The federation was made up from tribes that had settled near to what after Caldiran became, and still is, the border with Ottoman Turkey, before they were expatriated south. However, the literature that specializes on the Abbasid era or on the Qashgai does not seem to know about this expulsion (Boyle J A, Marsden D J, 1976; Newman A J 2006; Canby S R, 2009). The Christ symbol, in its digressed form on rugs from the southern Fars province is usually termed ‘the Qashgai göl and is thought to have migrated south with Turkmen members of the newly founded federation.

This is the frame of reference for Eagleton (1988; plate 63) who wonders how the Qashqai emblem may have found its way into a rug from the remote Barzani area in the Kurdish Taurus (in the neighbourhood of the Mountain Nestorians). Luckily, the textile featuring in this paper could be secured at or very near to its origin. This made it possible to build hypotheses on fresh facts and not on preconceived ideas (22).

The Advance of Christianity in

the Caucasus

The mission progressed from the south via Armenia, that at the time stretched much further in all directions; and possibly, through antique Albania. The beginnings in Armenia are thought to reach back to apostolic times, but this may be a biased account (Hage 2007). A first bishop with an Armenian name being mentioned is a certain Meruzhan of around the middle of the 3rd century. The foundation of the church is recorded a few decades later as having been affected by king Thrdat IV the Great (Tiridates, 298-330), who had spent his youth in Rome. Doing as he had experienced there, back home he suppressed Christianity during the first years of his reign. His attitude changed with Grigor Lusaworisch, the Enlightener (257-321), who had come to Tiridates from Caesarea in Cappadokia (Kayseri) and baptized him at around 313 or 314 according to Hage (2007). In the account of the Armenian Church, this baptism happened somewhat earlier, in 301. In any case, Armenia would have been the first country with a baptized Christian ruler. Grigor became the founder of the Grigorides, an hereditary priests’ dynasty that remained tied to the metropolitan of Caesarea and to the influence of the Greek church from the west, that brought the written Bible and liturgy (in Greek) to the still illiterate early Armenians.

There

had also been an Syrian-Aramaic influence from the early mission days

in the south of the country – with Syriac bible and liturgy -

represented by another priests’ dynasty, that of the Aghbianos

(Albianos) from Man(t)zikert, some 50 km north of Lake Van near the

modern town of Malazgirt. Mounting pressure on Armenia from

the

east and west by the Persian and Roman empires lead to internal strife,

as a result of which the western oriented Gregorides lost their power

to the Aghbianos well before the end of the 4th century. When Armenia

was divided between the two adjoining empires, the greater eastern part

came to Persia. The border ran in a somewhat crooked line from the

eastern Black Sea via the modern cities of Erzurum and Mus down to a

point somewhat east of Diyarbakir. The Sassanides who had

replaced the Parthians in the third century had adopted Zoroastrism as

a state religion. Converting from Zoroastrism to Christianity was a

capital crime and warranted death to all parties involved; to mission

among non-Zoroastrians in the new territories of the empire, however,

was sanctioned (Baumer 2006). Sassanid general attitude towards

Christianity was volatile, phases of appreciation are known; more usual

were restrictions, accompanied by severe persecutions from time to

time. With these political parameters acting as performance conditions

in the background, the stage was set for the Christian expansion into

Asia for centuries to come. The patriarchate then had its seat at

Seleucia-Kthesiphon.

To the south of the Great Caucasus, two kingdoms

established themselves in the first centuries AD. Lasika

(Colchis) in the west (Imereti) was an ally of Rome, and Kartli

(Iberia) in the east was contested between the Parthians (from 3rd

century onwards by the Sassanides) and the Roman Empire. That

the

apostle Andreas may have missioned here is thought of as a pious legend

by independent experts. Another legend involves a Caucasian

Jew

who allegedly travelled to Jerusalem, from where he took home an

unfinished gown that had been made for Jesus before his death (Hage

2007). The realistic content of the legend may be the that it

was

the Aramaic speaking Jews who provided the first stepping stones to the

mission.

Officially, church history in Georgia sets in with

Nino, the legendary female ascetic apostle from Cappadocia.

Due

to her actions, Iberia’s king turned Christian at around the middle of

the 4th century, with Imeret to the west soon following him.

As

in Armenia before, eyes at first had been turned west. Under

temporary Persian occupation in the first half of the 5th century,

however, the church tied itself to the Apostolic Church of the East,

whose Catholicos became the nominal head of the Christians in the

Caucasus. The second half of the 6th century first saw Georgia becoming

divided between Byzantium and Persia, and eventually coming under

Sassanid rule altogether. According to the records, Georgian

Christians had taken part in the Apostolic Eastern Church Synode in

419. Like their Christian brethren in other parts of the

empire,

Georgians suffered in the Sassanide anti-Christian pogroms in the

second half of the fifth and first half of the sixth

centuries. In the following centuries, the Georgian

church

struggled free from East-Syrian Dyophysitism as well as from the

Armenian Miaphysitism and joined the Christological position of

Byzantium around the beginning of 7th century.

During the

whole process, which outlasted Sassanid rule, the Church of the East

retained its influence in the region; and it continued to do so under

Islamic rule. Muhammad was allegedly identified as the prophet by an

East-Syrian monk. In the advent of Islam the Church of the East had

welcomed the change from the repeated measures of Sassanid suppression,

and cooperated and thrived – although its members remained second class

citizens. The Georgian Church consolidated itself as a national body

that offered a focus for a growing national identity, an important step

in preparation of national independence.

The now extinct church of the Caucasian Albanians, is as old as those of their neighbours and has been tightly bound to them. Its history exemplifies, how much politics were actually interwoven with church matters, even such as disputes over Christology. The volatility of change in Christology on the Albanian church seems to have superseded that of its neighbours even. Until the 11th century, Miaphysitism and Dyophysitism seem to have been at a constant tug of war.

When Armenia was divided in the late 4th century, the Albania of old with its capital and the seat of its Catholicoi at Tschoghay near Derbent in the north, had grown into New-Albania and more than doubled its size, because it had incorporated many groups of people with different languages in addition to those Armenians, who had settled in the lands between the Kura and the Aras (Hage 2007). Dowsett (1961) after Hage (2007) states, that in its great days, the Albanian church had missioned amongst the Turkish tribes (Huns) settling further north. Maybe, in the end, it was the lack of ethnic homogeneity as a result of expansion that hampered the creation of a focus of identity, as it successfully had happened in neighbouring Georgia. The constant church strives would have done the rest. Islamization had set in at the beginning of the 8th century, in the 11th century conciliar mosques existed in Partaw, Qabala and Shaki, the cities that were the creed of Caucasian Albanian Christianity (after Wikipedia org). The Albanian church is now extinct for nearly 900 years.

Epistemology and Method

The

composite symbol is a carefully balanced composite structure in which

individual components carry meaning and add to the overall form. The

author assumes that the delicate balance of the structure would be

maintained as long as the spiritual charging engine behind it did not

flaw or falter. But once this happened, due to change processes in the

social community, estrangement, disintegration and transformation would

have set in.

A nomadic or cottage weaver, in her individual

life, is tied to the greater process by tradition and family bonds, but

she also represents it and ‘translates’

it into something personal. This is what happens at the loom, the

interface between the weaver and the rug with its symbols and motifs.

Looking

at this interface from the perspective of the symbol, it could be

described as a process of accommodation and assimilation (23),

two underlying processes that act together and are as essential to one

another as are warp and weft as the material fundament of the fabric.

Accommodation describes the change process on the side of the symbol,

ultimately its transformation from symbol to ornament; assimilation

means the complementary by which the transforming symbol remains

attached to the flow of a changing social and religious environment.

Both sub-processes occur in increments. After many generations and

life-cycles, the name and the form of the symbol will have changed to

varying degree, but it has adhered to its central role, now as a significant motif

in the repertoire. It has become part of the heritage, while its

earlier religious significance had become defused and is now

inaccessible, after a new name or myth were attached to it.

This

is what seems to have happened in the field of rug motifs on a broad

front.

As has been mentioned earlier, the rug resembles others, in some aspects of its design, that are dated to the 13th - 16th centuries. These rugs are in the keep of Istanbul museums Vakiflar, TIEM and other collections. In every discussion of carpets, those would be regarded as very old or ‘classic’ (Denny W B, 2003). In an attempt to link any of those piled rugs with the Nestorian flat-weave at hand, a direct comparison from rug to rug on the level of main motifs, secondary ones and border ornaments, complemented by a structural comparison, is what normally would be undertaken. One could call it the traditional approach. Considering the immense time gap of more than thousand years between those ‘classic’ rugs and the symbol of Christ in the flat-weave, and the fundamental difference in technique, this approach seems intangible. It is also not exactly what the author hopes to be able to demonstrate. Instead, in a quasi-experimental and dynamic approach, the symbol of Christ is inducted right at the beginning of the proposed process: that early Nestorian Christians were functional in the creative process and in the distribution of textile patterns in Asia; that this took place in the context of their missionary activities in the early centuries of the new religion; that this process is traceable in the textile heritage of the nations that lay on their missionary path. The outcome can then be assessed as the degree of perceived concordance in a comparison of the composite symbol and exemplary rugs supposed to be related by a long chain of descent. Since the internal religious and value context remained rather stable within Nestorian communities, in contrast to external live conditions and political landscape, the composite symbol is assumed to have changed very little as well (24).

In other words, as the symbol at time zero had represented a significant Christology that distinguished it from other churches and, of course, from Islam, it should be traceable, distinguishable and recognizable, if it has survived at all. In this quest the author was looking out alertly for the following aspects in rugs to compare it with:

- a short balanced sceptre as the symbol of the hypostatic union set in a rhombus

- with two adjacent rhombi on either side, together forming a symbol of the trinity. The sceptre may have changed its shape. It would be essential though, that it echoes an ‘unmixed entity’ in the sense of dyophysitic Christology

- any other new arrangement that orchestrates what is being said under points 1 and 2

- a symmetrical arrangement of big horns on either side of a motif that resembles what is being said under points 1-3

- a kind of rod, root or stem, also serving as an symmetric axis, interrupted by the symbol of the hypostatic union and any ornament resembling the ‘vesica piscis’

- sets of birds flanking a ‘horned rhombus’ on four sides

- small rhomboids or similar, sandwiched between a central bigger one and flanking, angled palmettes on both sides

- two symmetrically arranged fishes right and left

of the sceptre bar (axis)

In

the list of tables only such rugs have been included that in addition

to (1-7) show a reasonable state of integrity, i.e. maintain a degree

of spatial order in the sense of a proximity-distance relationship,

that can be meaningfully related to the original symbol.

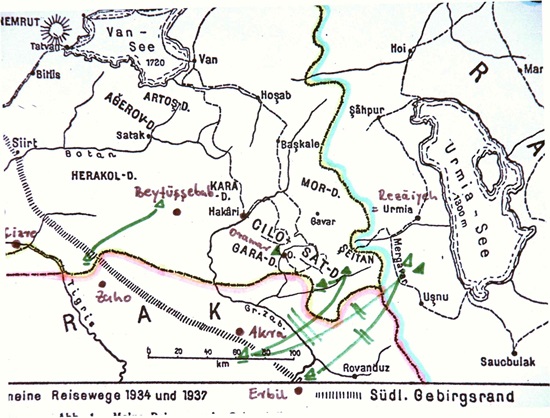

Map: The Roman-Persian border in the 5th century (Wikipedia.org):

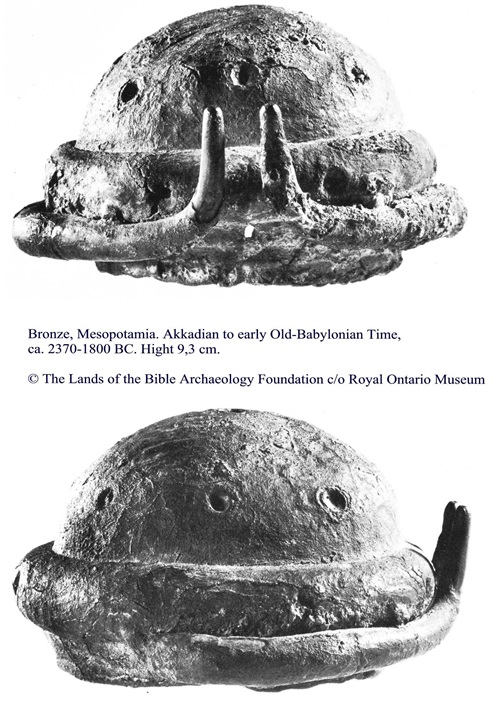

Plate 6: In the epic of Gilgamesh, his goddess mother Ninsun offers herself to the sun-god Shamash in an act of pleading his protection for her son on his quest to the cedar forest. Dressing up to the event includes her putting on a tiara which may have looked similar to this one:

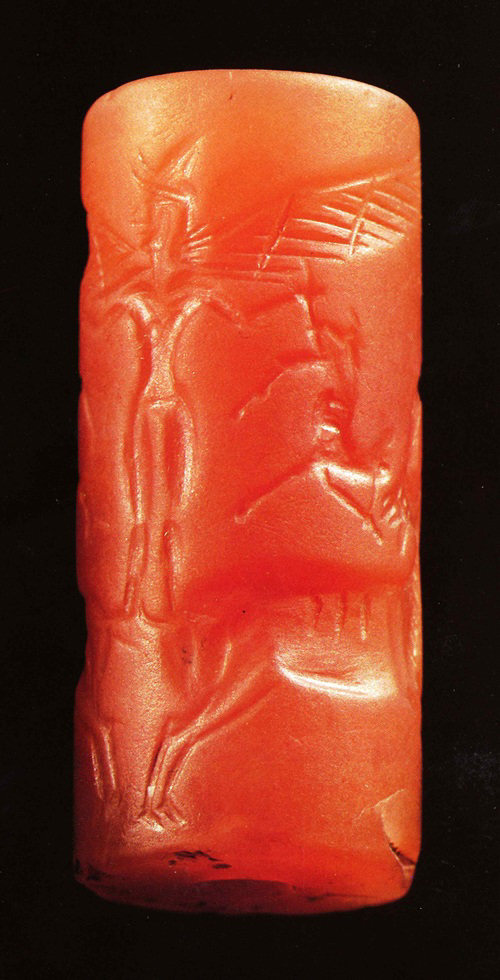

Plate 7: Cylinder Seal, Carnelian. North-Mesopotamia, middle-Assyrian time, ca. 1300 -1200 BC showing a winged goddess with horn-cap hovering over two antithetic horned animals.

© The Lands of the Bible Archaeology Foundation c/o Royal Ontario Museum

Plate 8: Rolling of seal from plate seven. It amazes to find constituent aspects of the later rug symbol fully evolved at such an early age: god (goddess), wings, antithetic powerful horns are easily identified.

Plate 10:

Detail from a German-Austrian Alpine Club Expedition Report Map

(Bobek,1938) with seasonal migration route between summer and winter

pastures of the Herki, crossing Christian (and Kurdish) settlement

areas on their trek until the borders were closed in the early

1930’ies. This is where the flat-weave comes from, and possibly the

Pazyryk rug as well - south of Lake Urmia and just outside the bottom

line of the map (Schürmann, 1982).

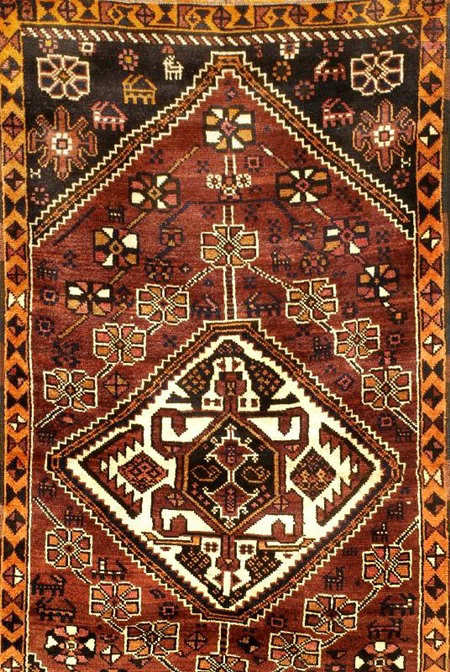

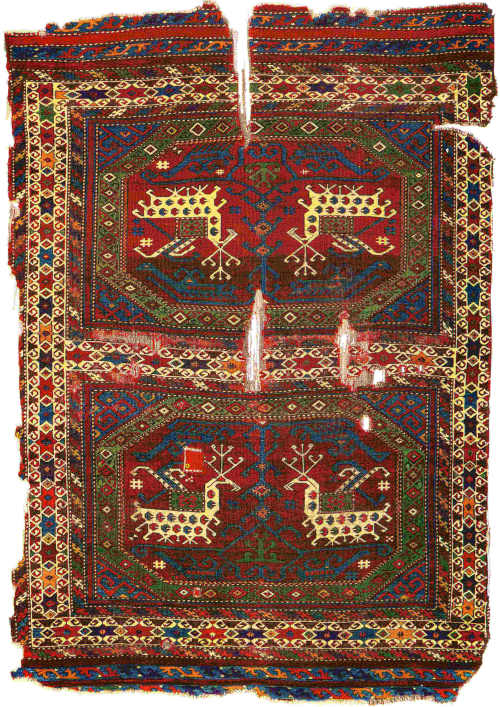

Plates 11,12: (from left) Rug auctioned in Germany in 2005; Eagleton (1988) plate 63 ‘Barzani rug’

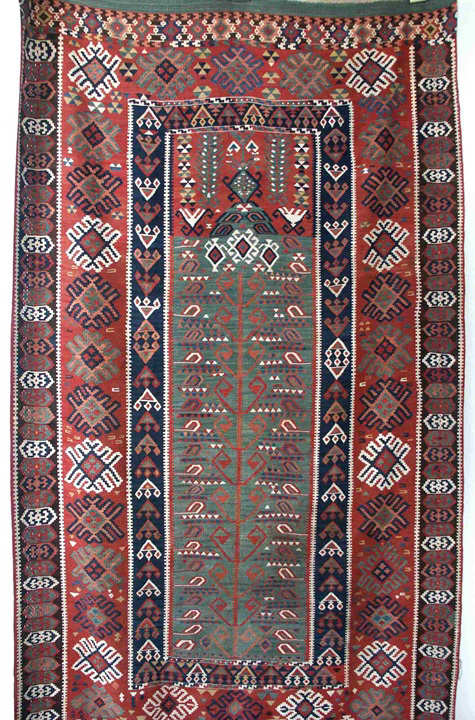

Plate 13: A 17th century rug from Central Anatolia, Konya area. The white rhombus has been clipped and has become an octagon; the lining birds are recognisable and are in position, so is thesymbol of the trinity in its extended Nestorian version, incorporating the symbol of the hypostatic union. One of the divine horns has been lost, perhaps in an old repair. The staff / axis is recognizable and some other aspects as well. The image has been taken from Bayraktaroglu S and Özcelik S (2007); TIEM InvNo727.

Plate 14: A 17th or 18th century rug from Central Anatolia, Karapinar area. The image has been taken from HALI 4/IV p. 371. The resemblance is astonishing although the birds seem to have metamorphosed somewhat. The religious symbolism is probably extinct.

Plates 15, 16: An East Anatolian rug dated to the 17th century by Balpinar and Hirsch (1988) and to the 15th century by Aslanapa and Yetkin (2005, 1991). Vakiflar Museum Istanbul, inv. no. E-1. Secondary winged creatures are flanking or sheltering the ‘main’ peacocks to the left and right of the stem / axis from below and above. Another significant association between the rug E-1 and the flat-weave exists: the rectangular compartments over the backs of the main creatures carry an emblem that is a minute version of the Christ symbol in the flat weave.

Plate 17: The ‘Marby Rug’ was discovered in the old wooden church of Marby in the Jamtland province of Sweden – an unlikely place for such a find one might think. Its origin lays in Eastern Anatolia or in Northwest Iran, 15th century (Lamm, 1985). As in the previous rug, secondary winged creatures are hovering over the peacocks left and right of the stem and axis. In this rug and the one before, the peacocks have substituted the fish flanking stem and axis in the composite symbol. The medallions rest on a white background, which always is a statement of exception similar to an aura. In the Christian age, peacocks were a symbol of the resurrection and of immortality. At least one incident is recorded, in which a textile with depicted peacocks served a symbolic purpose in such a context (25).

Plate 19: Fragment, TIEM Inv.no. 588 West or Central Anatolia,17-18th C (ICOC 2007)

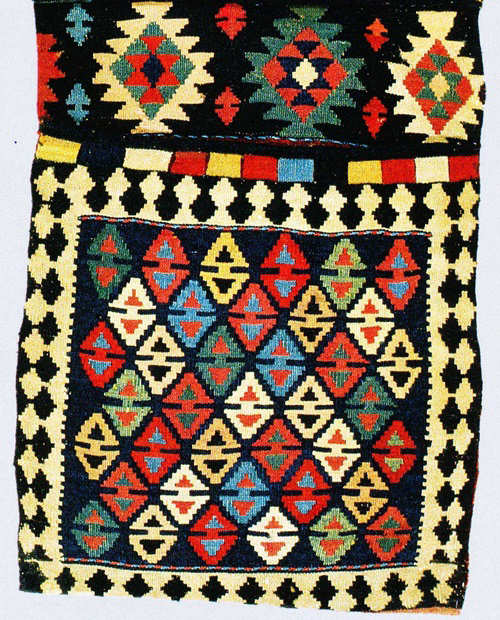

Plate 22: The symbol of the hypostatic union as an all-over field motif. Shahsavan bag-face, NW Iran, late 19th century (Plötze, 2001):

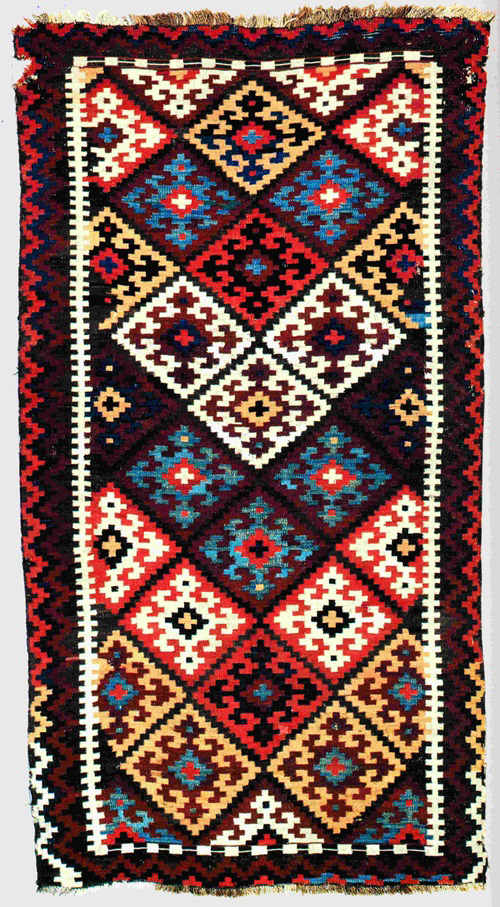

Plate 23: A kelim displaying a simplified version of the former composite symbol as an all-over field design. Luri tribe, West Iran, ca. 1900 (Plötze, 2001)

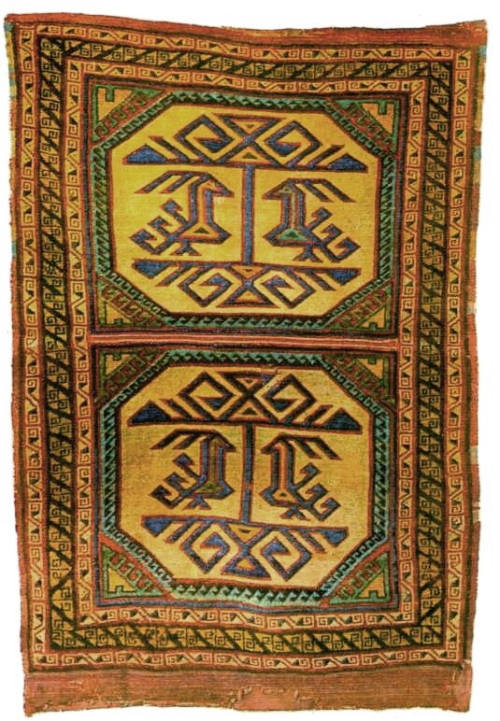

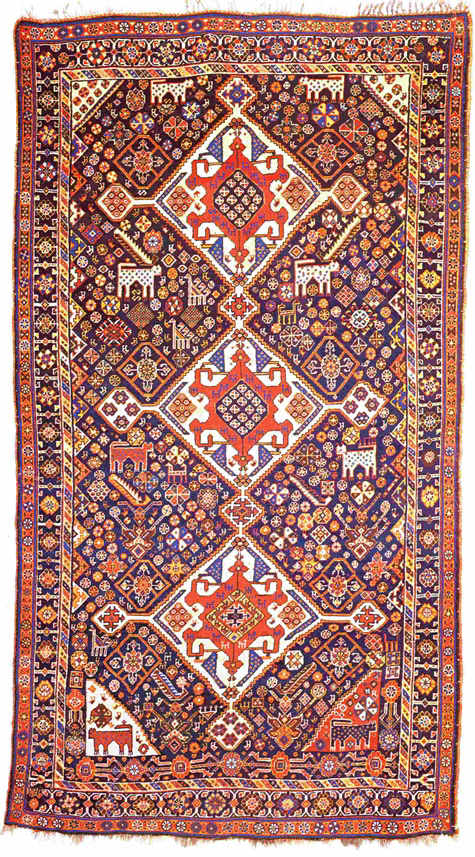

Plate 24: A splendid rug with what is generally thought of by rug experts as the ‘Qashqai-Göl’. Fars province, South-West Iran, end 19th century; plate 2 from Black and Loveless, 1979. This motif appears to be the nearest relative to the composite symbol outside a Christian context.

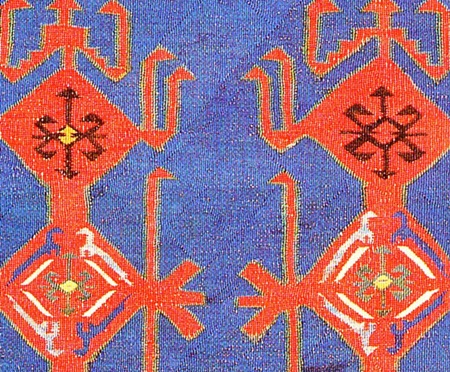

Plate 25: A 19th century ‘Moghan Shirvan’ rug (Eder 1990, plate 283). The divine horns are in proper place. The white background of the composite symbol has taken on an octagonal shape. The symbol of the hypostatic union is recognisable in two of the medallions. What looks like anchors that have been added may meant to be plant shoots. The heraldic birds are simplified to a degree that makes them recognisable to the knowledgeable only. As if to make up for this, minor birds abound in all forms and degree of stylisation.

Plate 27: ‘Borchaly’ - a very similar rug in the nomenclature of L. Kerimov (1983; plate 77). Somewhat less colourful rugs of this type can be found on the Turkish side of the border, where they are called ‘Kars Kazak’.

Plate 28: A Kuba region rug according to Opie (1992), plate 16.9. The composite symbol shows considerable digression and has been outgrown by the symbol of the hypostatic union; birds appear as stylised wings, stem, axes and stylised horns are in proper place, an interesting outcome of the transformation process.

Plate 29: This is another Kuba district rug, plate 286 from the book by Eiland& Eiland (1998). The transformation shows an interesting dynamic: like an explosion drawing of machinery components, the elements of the composite symbol have moved away from the centre while maintaining their relative positions in relation to one another. Stem / axis, hovering wings, birds, divine horns, the symbol of the hypostatic union are all there.

Plate 31: This Daghestan kelim, possibly from the Kumyk population ( Opie 1992; plate 16.6) is striking, and so is the transformation that took place. The hypostatic union has grown out of the central, rhombic medallion, each triplet containing a small version of the composite symbol similar to the border ornaments in the Erzurum area prayer kelim further up. Four birds are still lining the central rhombus, the shoots growing out of the axis at top and bottom are also recognisable.

Plate 33: The Turkish tribes and the Hephthalites (‘White Huns’) were first missionized from Daghestan (Baumer 2005; 2006) and, the Byzantines, so it is reported, were amazed at the sight of crosses tattooed on prisoners’ foreheads, belonging to those tribes. It seems permissible therefore, to cast a glance east in the direction of their habitat. The primary göls on the cover of the Rickmers Collection book (Pinner 1993) share several details with the composite symbol, ie the bucrania (divine horns) on the horizontal axis, and also the birds forming a crown at top and bottom on the vertical axis. This time they have taken on a somewhat estranged form, reminiscent of other Central Asian animal depictions with a typically backwards rotated head. Otherwise they are very similar to the ones in the Marby rug. The inner sets of bucrania are equipped with ledges or protrusions that give the impression of (horizontal) braids and prompt the association of birds’ heads. The colour schemata of this rug and in the composite symbol are a close match: red or brown-red, blue, black and white are the more or less sole colours. The centre rosettes in the göls look as if picked directly from the garland surrounding the composite symbol.

Plate 34: A similar theme and formal solution from further west; an ascension scene from the gospel book of Rabula (see page three of this paper) in West-Syrian orthodox style. Here, the four birds have become angels. Source for image: Wikipedia.org.

Conclusions

The hypothesis of the author set at the beginning is that early Nestorian Christians were functional in the creative process and in the distribution of textile patterns in Asia; that this took place in the context of their missionary activities in the early centuries of the new religion; and that this process is traceable in the textile heritage of the nations that lay on their missionary path. This hypothesis can be quasi-experimentally tested in the available image material. Methodological considerations can be boiled down to the simple question, whether the composite symbol of Jesus Christ in a flat-weave from the Mountain Nestorian retreat area in the Kurdish Taurus, can be conceived as a prototype for rug motifs in those regions.

To the author, the answer is a clear yes. Considering the velocity of change and as many pitched battles as have hardly been witnessed elsewhere, the symbol of Christ, in some regions, has turned out as deranged as could be expected, and it has remained remarkably intact in other regions. No detailed assertions can be made regarding any conditions, that may have helped or hindered in maintaining the integrity of the symbol other than the strict compliance of early Nestorian Christians to the Mosaic law and its ban on idols, that knew few exceptions. A remarkably integrated motif from northern Daghestan demonstrates, that even a tight Islamic context is no adverse condition. Abstractness and degree of stylisation of the symbol of Christ may have prompted an early and successful assimilation with the result, that until now those ensued motifs have been perceived as always having been accommodated firmly within an Islamic tradition.

Whilst the composite symbol of Christ forms the basis for many later rug motifs, it itself builds up on even earlier traditions, as has partly been demonstrated. As a consequence of this, the rugs and their symbols and ornaments as they present themselves to us should not be regarded as resting entirely in one cultural epoch, dynastic era or religious realm. Rather, they should be understood as transformations, reflecting developments and change processes that themselves are subject to the greater torrents of Near Eastern history and, of course, they are the results of individual achievements on the side of the weavers. All aspects combine in the lasting magic emanating from these rugs.

Notes

(1)

Revised version of a paper presented at the 2011 Volkmann-Treffen at

the Museum of Islamic Art, Pergamon Museum, Berlin 29th Oct. 2011.

‘Classical Carpets’ is the title of a book by Walter Denny (2002).

(2)

It looks very old, feels very old and shows no signs of heavy wear. The

latter is not surprising, given its assumed function as an altar rug.

Of one colour the author was not absolutely sure and a sample had been

given to Harald Böhmer who identified it as cold dyed light aubergine.

The sample was taken from a section of the stem or axis of the symbol

that indicated a re-usage of still older yarns. See endnote 14 for

this, last paragraph. Given the extreme adherence to tradition by the

Mountain Nestorians, it might be possible that the rug (is a true copy

of a true copy etc. going back many generations.

(3) The

identification of this rug may be a first step in the unearthing of

this heritage. In their original homelands of present day SE Turkey, NE

Iraq and South Azerbaijan, little in the way of textile artefacts has

survived or is known that bears direct witness to the great time of the

Nestorians, whose patriarch was seated in Seleucia Ctesiphon and

Baghdad in the middle ages and had overlooked a sea stretching far

wider than that of the pope in Rome at the time. The Nestorians’

history and special Christology, the schism that divided them (and

still does) from the other churches, are somewhat difficult to access.

Christoph Baumer (2005; 2006) provides a sound, thorough and amiably

written synopsis of the theme.

(4) More correctly, Assyrians, East-Syrians, or in its own modern diction, members of the "Holy Apostolic Catholic Assyrian Church of the East". However, here the term Nestorians is adhered to, because of the common understanding attached to it.

(5)

To Erdmann, the 'Classical Period’ of pile rug production comprises the

13th to 15th centuries, i.e. the Seldjuc and Mongol eras (1974, 1977).

Erdmann does not mention the Ottoman at this stage. The 16th century

demarcates the culmination and is post-classical to Erdmann. Walter

Denny (2002) includes more recent carpets in his catalogue of a Textile

Museum exhibition in 2002/3.

(6) Merv, on the silk road, was the

principal town in Khorassan and in size second only to Baghdad at the

time of the Sassanids and the Caliphate. Its first Nestorian bishop was

consecrated before the middle of the 4th century. Later, wandering

bishops and metropolitans reached the Hephtalites (‘White Huns’) and

migrated with the Turkmen tribes of whom many eventually adopted

Christianity (among other sources, Baumer Chr 2006). The strong

resemblance of several Turkmen Göls of the composite symbol discussed

in this paper suggests that rugs and rug symbols had had a function in

the mission process. In this sense, of the Turkmen groups later

migrating into Anatolia, some were probably travelling up to the source

of their rug designs. This worked into Erdmann’s theory

constitutes a necessary major revision of it.

(7) Azadi S, Kerimov L und Zollinger W, 2001; Bennett I, 1993; Eder D,

1990; Opie J, 1992; Schürmann U, 1990

(8)

This view has been explicitly expressed by Opie (1992) and has been

implied by Eder (1990) and Bennett (1993), with the latter authors

having contemplated the presence of Avar Thrones, animal hides and

other archaic symbols as central motifs. These observations should be

taken with some caution. They appear to be unconnected to identifiable

religious or historical circumstances and no approximate expressions in

objects belonging to other art forms are known that warrant such an

interpretation. In a ‘tapiologic

Salon’

hosted by the author on the Turkotek server, he had introduced the

Jewish Ark of Covenant into the discussion. This, appears as a motif on

rugs on the Caspian side of the Caucasus, where once a substantial, and

now greatly diminished Jewish minority settled (Nitz 2007).

(9)

The planned route was to branch off east at Hakkari from the one taken

by Anthony N. Landreau (1973) Kurdish Kilim Weaving in the Van-Hakkari

District of Eastern Turkey. Textile Museum Journal Vol III 4,

26-42. Reliable contacts in Van that were helpful in planning

and

organising had been established from 1974 on. In the summer of 1980

first signs appeared that the trip might no longer be feasible. From

the mid 1970’ies onward, Turkey had experienced a swirl of increasing

political violence between the left and the right. In the summer of

1980, civil war seemed to be a definite possibility. Parallel to this,

the PKK had launched a nationwide attack on public and military

institutions that interrupted civil life severely. Iran’s Islamic

Revolution was about to spill over into Turkey. When national flags

were torn down and burned in Konya and the green banner of Islam was

hoisted, the military may have thought that it had little option but to

move in with force. As a consequence, several eastern

provinces

were put under martial law and were closed to foreign visitors. Already

granted permissions and promised support became vain. In the spring of

1984 it was again possible for the author to travel to Hakkari. For a

revival of the project however, it was too late for a variety of

reasons.

(10) Eagleton (1988) plate 63 - depicts a more recent

pile rug that is very similar in its principal design. He wonders how a

Qashqai emblem could have found its way into a Barzani Kurdish rug from

NE Iraq, 1000 miles away from Qashqai settlement areas. Yet another

pile rug of this type has passed through auction in Germany in 2005. It

was advertised as a Qashqai rug. Both pile rugs are of a more recent

date, they are coarse weaves and lack the symbolic depth of the

flat-weave.

(11) Barzani aga

was the lord over a mixed Muslim Kurdish and Christian people. He was

nicknamed the ‘Christian Aga’ because of his tolerant attitude towards

his Christian vassals (Wigram& Wigram 1914, p. 153).

He also

seems to have had his own chicken to pluck with the Herki, ‘those hostes humani generis

… this horde of wandering robbers, the bane of all settled

communities.’ The authors relate how he quite cunningly managed to

retrieve some two or three thousand sheep and more from the Herki,

which they had previously lifted from his subjects. At this outcome

‘all the country was jubilant to see the original biters so badly bit’

(p. 149 ff).

(12) This probably is the material basis for the

inflationary use of the Herki attribution, that James Klingner (1999)

is unhappy about in his Hali article on rugs and flatweaves of the

Northern Zagros

(13) All over weft-wrapping technique; coloured wefts are wrapped

around one or two warps.

(14)

By the time of Timur Leng’s death in 1405, the Nestorian Christians who

he had persecuted so severely, also had ceased as a functional and

influential body in social life in all but a few townships and rural

communities. The patriarchs in office had begun to change their

positions frequently for security reasons and communities drew back in

order to find protection in or closer to the mountains or they

converted. Cultural exchange with the outside world became greatly

reduced. Accordingly, in the flat weave, no later design principle is

apparent,

than that of the ‘Holbein’ type and of an early combination of a

central medallion with a cartouche form. Although some

design aspects pay reference to much earlier periods, on the whole, the

rug echos designs not earlier than 14th or 15th century.

In

comparison with other flat-weaves for profane use that the author has

access to

and that come from the same region, the actual rug however, could be as

late

as mid 19th century. Obviously, this is too wide a gap to be

satisfactory. It is

the result of a complete cut-off from outside developments after

Timur.

All

who have written about the Nestorians in the 19th century agree in the

observation of their very traditional customs and their extreme poverty.

The

rug may have been reproduced from respective predecessors more than

once with painful accurateness in the way early scriptures and

illuminations were copied in monasteries. Reports mention very old

scriptures with the Mountain Nestorians but also narrate losses due to

exposure to the elements and inadequate keeping. To make

matters

still more complicated, there is an indication that the rug may have

been made with batches of wool retrieved from an earlier rug. The stem

or staff that runs right through the middle of the rug in its upper

section contains a number of small compartments, some of which show no

more than a faint hue of violet (see plate 2). This impression is

caused by a small amount of a very light and fluffy wool dyed violet in

standard dye density that is spun around a thread of natural light

wool. Behind this may be piety, because a Christ’s rug cannot be

discarded in an ordinary way, or it reflects on the impoverished

autarky of the Nestorians that had forced them to make a little last as

long as possible; or for both or still more reasons.

(15)

Besides some rugs of the ‘Holbein’ group, or more specifically to their

borders, an obvious association exists with some other rugs, namely the

‘Marby’ rug (Lamm, 1985), the ‘animal’ rug with the inventory no. E.1

in the Vakiflar Museum (Bayraktaroglu and Özcelik, 2007; Balpinar and

Hirsch 1988) and a rug of the Karapinar group depicted in HALI 4/IV

1982 p. 371. The latter three rugs share a particular design

feature: a stem or trunk as a vertical symmetric axis runs through the

medallion(-s), which is (are) lined in all four quadrants by elongated

animals, winged in most of the cases. Just to make sure that no

misunderstanding occurs, what is meant are those secondary creatures

flanking the ‘main’ or foreground creatures from below and above. In

the case of

the flat-weave, they form a kind of crown or mitre, and look

as

if they are attempting three-dimensionality.

Another significant

association between the rug E.1 and the flat-weave exists: the

rectangular compartments over the backs of the main creatures (peacocks

probably if one favours a more-down-to earth interpretation than

Balpinar and Hirsch, who see a ‘flying dervish in the shape of a dear’

in it) carry an emblem that is a minute version of the Christ symbol in

the flat weave.

(16) John 8, 12 (Addressing the people at the

temple

- Again Jesus spoke to them, saying, ‘I am the light of the world.

Whoever follows me, will never walk in darkness but will have the light

of life.’ ); Matthew 17, 2 (The

Tabor-Light - And he was transfigured before them, and his

face shone like the sun, and his clothes became dazzling white).

Jesus’

suffering at the cross apparently did not feature quite as strongly

with the Nestorians, as it did in the western churches and, in fact

still does. To the Nestorians, he was most prominently, the Christ of

the Resurrection. The white background of the composite symbol is, in

accordance with the above quotations, all about divinity and glory in

the resurrection. Interestingly, across church boundaries and schisms,

in Byzantine frescos as well as in Russian icons, we usually encounter

Jesus Christ in a white gown in the resurrection theme (Ouspensky L

(1962) pp 74 ff in Hammerschmidt E, Hauptmann P, Krüger P, Ouspensky

L& Schulz H-J (1962) Symbolik des orthodoxen Kirchengebäudes

und

der Ikone). It appears very likely, that the same passages of the Bible

have become constituent to the respective art styles.

(17) The

spatial arrangement of the symbol of Christ in the centre of an

ascending garland of rosettes, with the Patriarchal Cross in the

uppermost one, suggests a genealogical theme like the ‘Root of Jesse’ or ‘Jacobs Ladder.’

For the time being it remains open, whether the rosettes are

meant to represent Biblical figures and if, who could be featuring in

the bottom section of the rug. The stylised birds on wings that line

the inner flanks of the white rhombus, the ‘vesica piscis’,

forming something in the shape of a mitre, also

present a

bit of a riddle. In the above mentioned works of art they appear as

angels, which could speak for a old-testament Archangel tradition. Or

could they be another loan taken from the Mesopotamian tradition? A

Kassite cylinder seal shows the god Enki flanked by two sets of

double-shaped birds and, with two flanking fish-men by his feet. This

throws a surprising light on the two fishes in the composite

symbol (Pedde B (2009) Altorientalische Tiermotive in der

mittelalterlichen Kunst des Orients und Europas; Cat.-No. 91, plate 22).

(18)

The oldest known rug in existence, the Pazyryk Carpet, that was

released from a permafrost burial mound in the High Altai by Sergei

Rudenko in 1949 (Rudenko S I, 1970) is now being thought of to have

been commissioned by a Scythian noble, based at Sakic, a major

encampment at around 500 BC somewhat to the South of Lake Urmia in

Iranian Azerbaidschan, according to Ulrich Schürmann, who had discussed

the rug in an art-historic perspective. As the rug corresponds closely

with stone floor ornaments at the Assyrian palaces in Nineveh and

Khorsabad, the weavers of the Pazyryk Carpet and those of the ancestry

symbol of Christ may have belonged to the same stock. Sakic and the

Mountain Nestorian settlement areas in the Kurdish Taurus are situated

less than 150 km apart from one another; the Nestorian villages being

closer still to Khorsabad and Nineveh (120 km) than Sakic (180 km). The

design of the flat-weave survived in the mountains, but its origin

probably lay in the plain below, to the present day a Nestorian

Christian or, better, Assyrian Christian settlement area. Their

ancestors would make excellent suspects to have had a hand on the loom

with the Pazyryk carpet.

(19) The remains of the city are

situated on the western bank of river Tigris, north of the confluence

with the tributary Little Zab river, in the Al-Shirgat-District of the

Salah al-Din Governorate of modern day Iraq. The whole area had a long

Christian tradition.

(20)The Northern Kingdom of Israel was

invaded, conquered, and the population taken captive primarily by the

Neo-Assyrian monarchs, Tiglath-Pileser III and Shalmaneser V

in

the course of the second half of 8th century BC. The tribes exiled by

Assyria later became known as the Ten Lost Tribes of Israel.

(21)

One specific example, rug E.1 from the Vakiflar Museum has already been

discussed in endnote eleven. Other examples from other regions will be

given in the full paper.

(22) These preconceived ideas have led

to a somewhat ironic intellectual detour: Pinner (1979) and others with

him believed the ‘Qashqai’ emblem to originate from some unspecified

remote location in Central Asia - via Turkmen members of the Qashqai

federation and Oghuz predecessors; Eagleton (see note 2) on the other

hand puts the central medallion of his Barzani area rug down to the

Qashqai, settling one thousand miles south of NE Iraq, not realizing

that its authentic origin in all aspects lay virtually on his doorstep.

(23)

The interacting processes of assimilation and accomodation as they are

used in this context are a loan taken from Jean Piaget’s

conceptualisation of developmental processes. Jean Piaget has become a

galleon head of modern developmental psychology, and has made important

contributions to epistemology and science theory (Jean Piaget 1972a,

1972b, 1973, 1974, 1989, 2001, 2004, 2007).

(24) Every early visitor to the Nestorians had commented on their conservatism and adherence to old ways, as if living in a past age.

(25) Cnut the Great (King Canute) ‐ King of England, Denmark, Norway and parts of Sweden ‐ visited the tomb of Edmund Ironside (Edmund II), his predecessor and former opponent, on the anniversary of his death in 1016 and laid a cloak decorated with peacocks on it to assist in his salvation, peacocks symbolising resurrection (M K Lawson (2004) Edmund II. Oxford Online DNB ‐ after Wikipedia.org).