Home Page Discussion

The Salon du Tapis d'Orient is a moderated discussion group in the manner of the 19th century salon devoted to oriental rugs and textiles and all aspects of their appreciation. Please include your full name and e-mail address in your posting.

Salon 132: Locations of Major Turkmen Tribes (16th to 19th Centuries)

by Pierre Galafassi

Although history and geography are supposed to deal with reasonably clear and documented information, most rug books are vague and at times even contradictory about the locations of Turkmen tribes. You say that they were nomads, so they had no fixed locations? Right, but even nomads find it difficult to achieve ubiquity. Therefore, I tried to summarize what a highly competent and respected historian wrote about Turkmen and what a handful of serious nineteenth century visitors got directly from the horse’s mouth. The following maps and comments are heavily borrowed from Yuri Bregel’s outstanding Historical Atlas of Central Asia. I merely tried to focus on my favorite Turkmen, simplifying and dividing Bregel’s complex maps until they were compatible with my underperforming synapses.

During the 16th century the Turkmen occupied an area of desert and dry steppe. Their range was limited on the north by Qalmik-, later by Kazakh tribes; on the west by the Caspian sea; on the east by the Aral sea, Khorezm (later known as Khiva khanate) and the dried bed of the eastern Uzboy River; on the south by the Gorgan River and the western part of the Kopet-Dagh range. Their territory included the Mangyshlak peninsula, the Üst-Yurt plateau and the Balkhan hills (1). Except for the Atrek, Gorgan and a few small rivers in the Mangyshlak peninsula, there were only seasonal rivulets (mostly in the Balkans). The Uzboy River had fully dried up centuries earlier.

Vambery (2) mentioned that the Üst-Yurt plateau was a trifle greener than the nearby Qara-Qum desert and apparently allowed sizable wildlife and cattle raising, while Mouraviev (3) observed that there were wells in and along the dried bed of the Uzboy that were rather less brackish than most others and that the scenery was greener than in the nearby dry steppe. Nineteenth century visitors also mentioned that after the rain and snow seasons, a large number of temporary pools, formed in clay-lined depressions, dotted the desert. It seems quite obvious that the area was suitable for horizontal nomadism only (4), with small and scattered yurt villages near permanent wells, while herds of camels, sheep, goats or horses, migrated from pastures to wells under the guidance of junior tribesmen.

Why were the Turkmen confined to such a barren area?

Bregel (5) gives us a hint "... The Mongols were obviously little interested in the area, which was unfit for the Mongol type of horse-breeding economy ...." Stronger nomadic tribes, such as the Qalmiks, kept possession of the fat herbaceous steppe, the southern limit of which is about 200 km north of Turkmen territory. Besides, the Turkmen were elusive and reluctant potential slaves, there was no city to pillage and destroy nor any oases to convert into pasture in the remote and barren territory. The only dwellings mentioned on Bregel’s maps are a Parthian border fort and an Islamic village on the Uzboy, both deserted ruins long before the Turkmen settled the area.(6).

IMHO, after the successive mass emigrations of the Seljuk-, Ak-Khoyunlu-, Kara-Khoyunlu- or Afshar Turkmen those remaining or returning were too few to fight the armies of the various Timurid-, Uzbek- and Persian kingdoms (to name just a few) or to challenge the Qalmik- or Kazakh confederations for better pastures. It is noteworthy that except for a couple of Uzbek- and Qalmik-raids, nobody really ever disturbed the Turkmen in their territory until the end of the sixteenth century.

Locations of the main tribes during the sixteenth century

According to Bregel (7) the Turkmen were grouped in four tribal confederations: From north to south, the Esen-Eli (Chodor, Igdir, Arabachi and Abdal), the Ischki Salor (apparently only consisting of Salor tribesmen), the Dasqi Salor (next to Salor; this confederation also consisted of offspring tribes that were later called Saryk and Ersari, as well as of less directly related tribes such as the Tekke and Yomud) and the Sayinkhanis (mainly composed of the Göklen and Yemreli).

Most 19th century visitors mention that the Turkmen had strong resistance to authority. Their khans and elders had very limited power (Kushid Kuli Khan, the absolute ruler of the Tekke from 1857 to 1877, was an exception). These confederations of tribes were, therefore, very loose; there is no evidence of any strong political unions (8, 9).

Why did they start moving out of their traditional territory by end of the 16th century?

There is no single reason that is widely agreed upon: Bregel hints at changing climate conditions, at overpopulation, at weakened and divided Uzbek khanates (mainly Bokhara and Khiva) whose rulers customarily enlisted Turkmen military support in their intra- and inter-khanate struggles and in campaigns against the Persians. Consequently, many Turkmen tribes migrated closer to the urban centers of the khanates, which came to depend too heavily upon the Turkmen for their military forces. He also mentions an increased pressure from the Qalmik- and (later) Kazakh nomads on the northern border of the Mangyshlak peninsula (10), the latter themselves pushed over by the Junghars (from the east) and by Russians settlers (from the north).

The romantic belief, common in carpetologist circles, of a defeat of the Salors and a resulting explosion of the Dashqi Salor confederation is not mentioned by Bregel. The separation apparently took place very gradually over more than 50 years. The tribes did not necessarily move in separate directions, nor did all clans of a given tribe move contemporaneously. For all we know this slow process might have been mostly peaceful, at least measured by usual Turkmen standards.

Surely the weakness of the last Safavid Persian Shahs (first third of the eighteenth century) lured the Tekke southeast, towards the fertile northern Kopet-Dagh piedmont settled by Turkmen clients of Persia, and the destruction of Merv by the Bokharan army (1787-1788) was seen as a golden opportunity by the Saryk and the Salor for seizing the deserted oasis.

The farming-based economy of the main Uzbek khanates was heavily dependent on slave manpower and provided a welcome new business opportunity and a lot of fun for the Turkmen, who discovered an unlimited supply of potential slaves in the poorly defended Khorassan- and Mazandaran provinces of Persia. The logistics of this lucrative industry may have had a role in some tribal relocations, too.

Movements of the main Turkmen tribes between the sixteenth and the end of the nineteenth century

In order to make Bregel’s information easily understandable (even for me!) I created a separate map for each major tribe’s migrations, hoping to have correctly interpreted his thoughts.

The tribes were not homogeneous groups, moving and living together. While "keeping distinction between the clans with utmost formality" (11), the Turkmen found it perfectly acceptable to share pastures or oases with clans from other Turkmen tribes. This did not necessarily mean that the smaller clans were kept in a state of subserviency; certainly, they were not enslaved. For example, during the 19th century the banks of the middle Amu Darya were shared by many Turkmen- and non-Turkmen populations. Among the former, in addition to the Ersari majority, there were sizable Salor-, Sakar-, Khizir-Eli, Murchali- and Arabachi aouls (14). The major tribes even often tried to lure small clans, especially the Shikhs and Khoja owlads, which occupied a particularly honored position as holy tribes, into settling on their territory (15).

Movements of the Salor

The Salor were already an important Oghuz tribe in the 11th century and were involved in the western expansion of Seldjuk-, Akh-Koyunlu- or Kara-Koyunlu Turks. Some Salor clans also moved east and were still living in Tibet during the 19th century (16). During the 16th century, the Salor were the most prestigious Turkmen tribe and a major component of both the Ishki Salor- and the Dashki Salor confederations, which roamed the Mangyshlak peninsula, the southern part of the Üst -Yurt plateau and the Balkhan hills. During the early 17th century, the Salor started moving toward the fringes of the Khoresm oasis, perhaps called by feuding Uzbek parties. They played important political and military roles during the first half of the century, but had to leave Khiva in 1667 because of the anti-Turkmen policy of a strong ruler (Abu’l Ghazi Khan) and his Yomud cavalry. Part of the tribe (joined by the Saryk) then settled on the Amu Darya, north of Charjuy, probably serving in the Bokharan army. Another group moved to the northeastern part of the Kopet-Dagh piedmont, near the Tezhen delta.(17)

After the complete destruction of the last city of Merv by the Bukharan ruler Shah Murad and the relocation of its surviving population in Bukhara (in 1788-1789), part of the Amu Darya Salor (and nearly all their Saryk friends) occupied the deserted Merv oasis, where Wolff met them in 1845 (18). The Salor were a minority; the Saryk were the majority population. Some other Salor went up the Murghab river and settled in Yolatan (19) and Pendj-deh, a third fraction joined their brethren near the Tezhen delta and upriver, around Serakhs, while another group remained near the banks of the Amu Darya, where Burnes met a wealthy Salor elder in 1831: "... Soobhan Verdi Ghilich (the-sword-given-by-god) was of the tribe of Salor, the noblest of the Turkomans ..." (20).

When Burnes later (in 1831) stayed ten days at Serakhs, the local Salor were still a militarily powerful and feared tribe, "... the greatest haunt of the Turkoman robbers ... (21), keeping over 3,000 Persians slaves (22) and a captive ambassador to boot (23). Their standard of living amazed the British officer: "I was very agreeably surprised to find these wandering people living, here at least, in luxury ..." (24). Shortly after Burnes' stay, in 1832 the crown prince of Persia, Abbas Mirza, led a strong army against the Salor, completely defeating and dispersing them through Khorassan (25). Chastised Salor were later allowed to return to Serakhs and to Zur-abad (upriver), mainly, I suppose, after 1857 (H. de Blocqueville in 1860, O’Donovan and Lessar in 1881-1882 mention them in this area). But their wealth was gone, their fighting spirit broken and they apparently behaved fully to the Shah’s satisfaction. Their state of poverty was noted by the Russians, Lessar and Alikhanoff (*).

In 1857 the Persian army inflicted a severe defeat on the Tekke, who had moved into the vacuum left by the Salor near Serakhs. The enraged Tekke wasted no time in throwing the Saryk and their Salor friends out of the Merv oasis and relocating there. Although de Blocqueville in 1860 (26) and O’Donovan in 1881 (27) still mention an aoul of Salor in Merv, most left the oasis and went either up the Murghab to Yolatan and Pendj-deh with the Saryk or moved up the Tezhen to a deserted Serakhs (the area was much too exposed to Turkmen raids for any civilian Persian population to settle there permanently), where they were joined by some of the vanquished of 1832. In 1889, Alikhanoff, then Governor of Merv, visited the influential local Salor leader, Teke khan (sic) (28). Apparently, the Salor had partly recovered their old standard of living (*).

After the Russian conquest in 1884-1885, Salor clans could be found on the middle Amu Darya, the Merv oasis (an aoul of 170 families according to O’Donovan (*)), in the Serakhs/Zur-Abad area, and on the Murghab River between Yolatan and Pendj-deh.

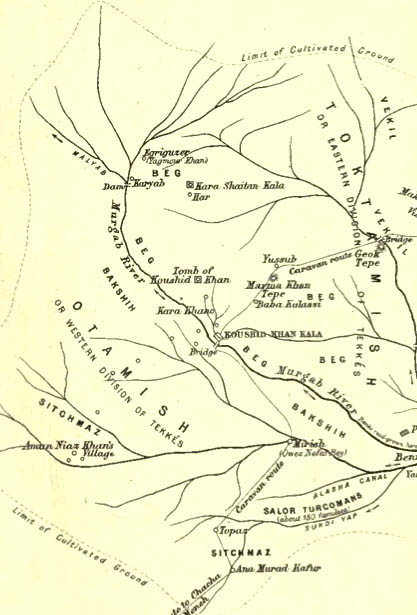

(*) Compared to modern carpetologists, the nineteenth century visitors to the Turkmen made a refreshing show of unanimity, agreeing on nearly everything. A major exception to this rule is the information given by the Russians, Lessar and Alikhanoff, and by the Briton, O’Donovan, all of them extremely well informed, since they all spent months in the area in 1881-1882. The Russians insisted that the Merv Tekke were victimizing about 2,000 Salor families and depicted the Salor, both in Merv and in Serakhs, as being destitute. O’Donovan mentioned only 170 Salor families in Merv, living a free life on a fertile part of the oasis (see map below). Although the Tekke were the ruling tribe, other Turkmen clans like the Mjaour-Iliat and Agur Bashe were treated as guests (mihman) and friends (doghan) (12).

Their status as free tribesmen is illustrated by two anecdotes. When Persia attacked the Merv Tekke in 1860, the local Salor at first remained neutral and only decided to join the fight against the Persians when the latter unwittingly raided their aoul (13). In 1881, when a Persian ambassador to Merv secretely negotiated their emigration to Serakhs, only a minority accepted. Although they were brought back by the yassaouls (local police force) they were not punished for their attempted desertion, since the Tekkes elders agreed that there was no formal interdiction of emigration (65).

I am not in a position to know who was lying and why. I would merely like to mention that in 1881-1882, Russia was posing as the natural protector of all Turkmen, was salivating in the expectation of annexing Serakhs (home of poor Salor victimized by Persians and Tekke and, incidentally, a door to Herat and to British India) and looking for a good pretext for annexing Merv (home of other impoverished Salor victimized by brutal Tekke slave hunters and, incidentally, another door to an easy route to the heart of Afghanistan and British India).

Movements of the Tekke

Members of the Dasqi Salor confederation, the Tekke were of mixed ascendance, less directly related to the Oghuz than the Salor, but had perhaps a common origin with the Yomud (29). During the 17th century they underwent a major population increase and started infiltrating the (nominally Persian) northern piedmont of the Kopet-Dagh (Akhal). During the early 18th century, after decades of guerrilla warfare, they expelled the Yemreli Turkmen which had settled there by mid-17th century and a few less important tribes as well (Alieli, Qaradashli). The Tekke conquered this narrow but fertile area and challenged the last Safavid Shahs (30). It seems that even the military genius of Nadir Shah, who created a short-lived new Persian dynasty, could not stop their progress.

As O’Donovan wrote (31) ".... The Teke Turkomans, who, according to all accounts, were a set of irreclaimable scamps, passed their leisure time in making raids on their neighbors. When victorious, they killed the entire male adult population, and carried off the women and children as slaves ...". They were raiding deep into Persia, rarely being challenged by an effete Persian army. Except for a defeat against the khan of Khiva in 1827 (32) and a temporary emigration to Khiva of some Teke around this time, the Akhal Tekke population kept growing in number and might.

After the 1832 defeat inflicted by the Persian crown prince Abbas Mirza to the Serakhs Salor, some Akhal Tekke moved deeper into the Tezhen delta (Atak) and the empty Serakhs area. J. Wolff signals their aouls there in 1845 (33), from where they made themselves a prime nuisance for the eastern Khorassan- and western Afghanistan populations. In 1855 they routed a Khivan expedition, killed the ruling khan and sent his head to the Shah, probably triggering the general revolt of all Turkmen tribes previously under Khivan nominal control.

In 1856, a Persian army finally managed to defeat the Serakhs Tekke and to oust them from the area. The Tekke found their Buonaparte in Kushid Kuli Khan (34). Under his absolute rule, they stormed Porsa Kala, the mighty Saryk fortress in the Merv oasis in 1857 forcing both the Saryk and the local Salor minority to move up the Murghab River, to the Yolatan- and Pendj-deh oases. In 1860, a confident but incompetent Persian army attacked the Merv Tekke and was routed. Most of the Persian army ended up as a glut on the Bokhara- and Khiva slave markets. Monsieur de Blocqueville, a French officer enlisted in the Persian army and an artist, was held captive for 14 months by the Tekke in Merv, enjoyed his stay (a case of Stockholm syndrome, I guess) and wrote an interesting account (35). After this victory, none of their neighbors dared to challenge the Merv Tekke again until the Russian takeover. Around 1875, the steady growth of the Merv population and their rather limited talent and taste for farming (36, 37), caused a return of part of the poorer or younger Merv Tekke to the Tezhen delta (Atak) and to Serakhs again (38), where they had a rather difficult life sharing the area with similarly destitute Salor clans, paying taxes to predatory Persian princelings and, after 1881, exposed to the raids of increasingly emboldened and vengeful Persians.

Their brethren Akhal-Teke enjoyed slave hunting, their favorite sport, in peace until the bloody storming of their Yengi Sheher (Geok Tepe) fortress by Skobeleff’s Russian army in 1881. After their defeat, most surviving Akhal Tekke returned to their aouls and enjoyed the Tzar’s peace. In 1884, a strong pro-Russian party, mainly created by Alikhanoff’s clever diplomacy (39), led to an easy takeover of Merv.

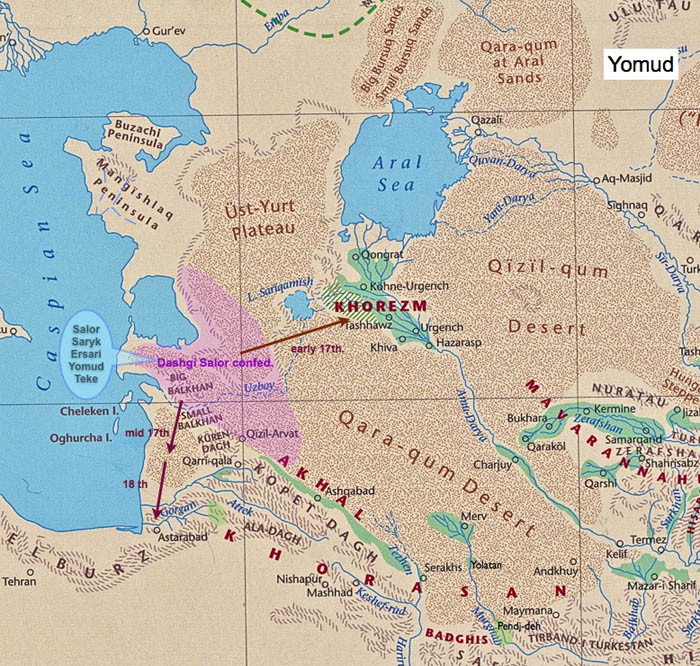

Movements of the Yomud

The Yomud were part of the Dashqi Salor confederation, but probably were more related to the Tekke than to the Salor (40). By the mid-17th century they began crossing the dry bed of the Uzboy and encroaching on the territory of the Göklen and Yemreli, pushing them south and east. Progressively during the 18th century, the Yomud settled the whole area down to the Gorgan River. Both Vambery in 1865 and O’Donovan in 1880 lived with Yomud on the shore of the Caspian sea, between the Atrek and the Gorgan. O’Donovan found them quite civilized compared to the bloodthirsty Akhal Tekke. I suppose that he meant that the nice Yomud enslaved Persians with a kindly smile.

Some Yomud started brilliant careers as pirates (and, incidentally, as fishermen) on the Caspian Sea, supplying the Khiva slave market with a welcome variety of Russians and Caucasians, next to commodity Persians (41). During the early 17th century, another part of the Yomud moved to an area southwest of Khiva. Like other major Turkmen tribes (Salor, Tekke, Saryk, Ersari) they meddled in internal Khivan affairs, fighting for various Uzbek candidates to the throne of the khanate.They were instrumental in expelling the Salor and Tekke from the khanate in 1667 (42). They even stormed and wreaked havoc in the capital a few times (for example in 1743, after a courtesy visit by Nadir Shah’s army had much depressed the Uzbeks, and again in 1770), only to be expelled a few months later (43). Unlike the other major tribes, they never durably left the Khiva area and kept their uneasy alliance with the Uzbek khans, despite some beatings inflicted by an occasional strong ruler. Until the Russian takeover, the Yomud frequently formed the major and most competent part of the Khivan army (44).

The Bayram-Shali Yomud mostly chose to move northeast, while the Qara-Choka Yomud moved mostly south, but the clans kept close links. Both still nomadized in and around the Balkhan hills and both chased hapless Persians south of the Gorgan River and even on the southern shores of the Caspian. Groups of Yomud, could occasionally be found far from their main territory: J. Abbott, traveling through the Pendj-deh oasis in 1843, received a warm welcome in one of their aouls and praised their beautiful carpets (45). In 1873, von Kaufman’s army easily conquered the Khiva khanate turning it into a Russian protectorate. The Yomud cavalry made a brave stand against the Russians, a fact which perhaps induced von Kaufman into teaching them a lesson, a nearly successful attempt at genocide.

In 1879, when the Russians started their final attack of the Akhal Tekke from bases on the southeastern shore of the Caspian Sea, the Yomud prudently accepted Russian rule and fought along with the Russian army (a rare case of protracted inter-Turkmen warfare). In the rout following the storming of Geok Tepe in 1881, the Yomud cavalry competed with the Russian Cossaks in massacring fleeing Tekke civilians. The Yomud also gracefully accepted ending their slave hunting activity, much to the Shah’s delight.

Movements of the Saryk

The Saryk claimed to be offsprings of the Salor. It seems that they kept a strong link with the "noblest of the Turkmen tribes". In the early 17th century they both moved to Khiva. All Saryk left Khiva in 1667, together with part of the Salor and the Ersari, joining the Bokhara khanate and settling in the Middle Amu Darya area. I suppose that Saryk were part of the Bokharan army that destroyed the city of Merv in 1788, a hypothesis which would explain why the whole of the Saryk tribe could so quickly populate the deserted oasis. There, they were occasionally bothered by a Khivan army, Khiva gaining nominal control of the oasis from Bokhara after 1823. For example, in 1831 Burnes came across a Khivan customs officer, who doubled as tour operator organizing Saryk raids (alamans) into Persia, for the greatest benefit of the Khivan khan (46). Besides the Salor, a few Tekke were also probably sharing the oasis with the leading Saryk tribe (47).

At the time of Burnes’ visit, the Saryk were still prevalently cattle-, camel- and sheep raisers : "... They have but few fields, and one or two individuals may tend their countless flocks at pasture ..." (48). The Saryk started rebuilding the dams destroyed by the Bokharan army. They also built a huge adobe fortress, Porsa Kala, which served as permanent site for part of the tribe’s yurts near the main dam. In 1857, outnumbered by enraged Tekke led by their charismatic leader (Kushid Kuly Khan), the Saryk had to leave the Merv oasis and moved upriver to Yolatan and to the larger Pendj-deh oasis. As usual, the defeated tribe displaced an even weaker tribe, in this case the Jemshidi, who had to look for a new home further upriver.

While the Yolatan Saryk were "on speaking terms" with their strong neighbors, the Pendj-deh Saryk kept their grudge against the Tekke and did not mind raiding them for mere fun, being paid back, of course, with the same coin by the Merv Tekke (49).(**) In 1884, shortly after the Russians occupied Merv, Alikhanoff easily persuaded all Saryk to pledge allegiance to the Tzar, too. In 1885, the joint Tekke-Saryk cavalry, led by Alikhanoff, made a brilliant show near Pendj-deh, when the Russian troops defeated an Afghan army and annexed the area (50, 51)

(**) The otherwise rather honest Turkmen had peculiar ethical rules, or a twisted sense of humor, whenever "alamans" were involved. While stealing anything from a fellow tribesman’s yurt was not an acceptable behavior and was practically unheard of, they were not above raiding a caravan belonging to somebody of the same tribe whenever a nice booty could be made. O’Donovan (52) mentions the case of a Tekke khan’s caravan being plundered on its way back from Meshed by a few Tekke youngsters. While the khan was beside himself with wrath, all Merv was laughing out loud, considering it a capital joke. The youngsters got caught by the "yassaouls" and the khan recovered his goods, but the "ogri" (robbers) were merely lectured by elders and let off without any punishment.

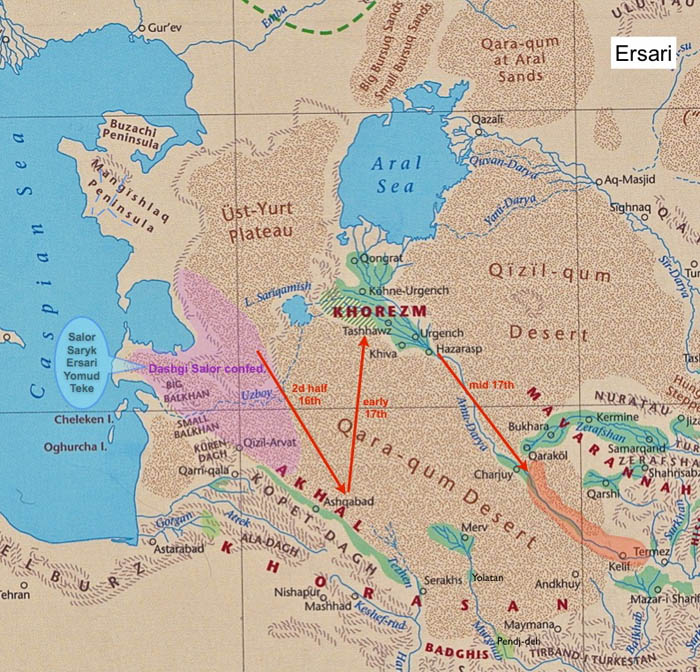

Movements of the Ersari

The Ersaris also claimed a Salor filiation. Mouraviev saw their eponym founder’s tomb, on the Üst-Yurt plateau, on his way to Khiva in 1819 (53). They started leaving the plateau during the second half of the 16th century for oases on the northern piedmont of the Kopet-Dagh, where Abdul Ghazi (future khan of Khiva) still encountered some of their aouls in 1641, by which time most Ersaris had already moved to the Khiva khanate (early 17th century). In 1667, Abdul Ghazi and the Khivan Yomud persuaded them to move to their final destination, the Middle Amu Darya, where they served in the Bokharan army and provided escort to caravans. There, many Ersari settled in adobe houses, switching to farming and silkworm rearing (54) instead of the usual semi-nomadic mix of pastoral and small scale agricultural occupations of most other Turkmen. They inhabited both banks of the Amu Darya between Charjuy and Kelif (55). In 1831 Burnes stayed a month in such a permanent Ersari village near Qaraköl, on the right bank of the river (56) and noted that they were a more urban lot than their brethren due to their contacts with the Bokhara metropolis. However, they apparently never turned soft, since O’Donovan mentioned (in 1881) that the mighty Merv Tekke feared their raids enough to move only in heavily armed parties near the northeastern fringe of their own oasis (57).

According to the Merv Tekke (connoisseurs!), these Ersari competed with the Akhal Tekke for the glorious title of Most Obnoxious Turkmen Robbers. Eventually, some Ersari moved further south, to the areas of Termez, Andkoy and Mazar-i Sharif, the latter still being one of their strongholds. Many MAD Ersari joined them in Afghanistan during Stalin’s purges. As mentioned before, the Ersari were not at all the only inhabitants of the Middle Amu Darya area; they shared it with over half a dozen smaller Turkmen clans as well as with (mostly settled) Uzbeks,Tadjiks and their large enslaved workforce.

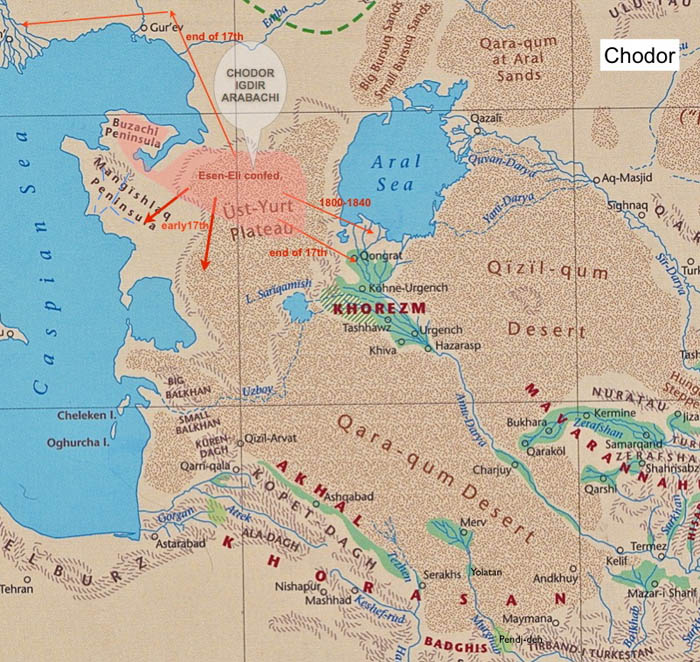

Movements of the Chodor

Like the Salor, the Chodor were already a large and respected Oghuz tribe in the 11th century. In the 16th century they were the most important tribe of the Esen-Eli confederation, and occupied the Buzachi peninsula and the northern part of the Ûst-Yurt plateau in direct contact with strong Qalmik tribes. During the early 17th century they gradually moved south, probably repopulating pastures left unused by the leaving Ichki Salor.

By the end of the 17th century and the beginning of the 18th century, further waves of emigration went, partly in direction of the Khiva khanate, partly towards the lower Volga and the Caucasus (58). One cause for these moves surely was the pressure of the Kazakhs on the Qalmiks and later the pressure of the Junghars and Russian settlers on the Kazakhs. The losing tribe, as usual, tried to compensate for lost pasture land by invading the territory of a still weaker tribe, in this case the Chodor.

Like most Turkmen tribes, the Chodor had a rather stormy relationship with Khiva: they were often drafted into the Khivan army, enjoyed joining feuding Uzbek clans, offered protection to Khivan caravans en route to Russia via a makeshift port in the Mangyshlak peninsula (59, 60), traded slaves for grain (61) or were getting bashed by stronger Khiva khans trying to teach them a more positive attitude towards taxes and a lesser interest for Khivan internal affairs. However, like their Yomud usual allies and unlike all other major Turkmen tribes, the Chodor usually kept strong links with Khiva and stayed at the northwestern fringes of the oasis.

Movements of the Göklen

By the middle of the 17th century, the much smaller Göklen tribe, further weakened by a severe defeat at the hands of the Safavid Persians, had to give way to expanding Yomud and to move to the wooded hills of the upper Gorgan River (62) and to the Sumbar Valley on the southern rim of the Kopet-Dagh (63). They were among the first Turkmen to settle in permanent villages. They accepted Persian rule, even though the tax man usually had to visit their aouls with the support of three or four regiments. Burnes travelled with a unit of Göklen cavalry serving in the Persian army, stayed at their aouls and found their territory quite charming "... No scene could be more enchanting than that on which we had now entered: the hills were wooded to the summit, and the hue of the different trees was so varied and bright, as hardly to appear natural. A rivulet flowed through the dell; and almost every fruit grew in a state of nature. The fig, the vine, pomegranate, raspberry, black currant, and the hazel, shot up everywhere ..." (64). This was a unique environment in the otherwise barren Turkmen territory. The description given in some rug books of the Göklan as destitute hillbillies surely would not fit well with Burnes’ opinion.

Locations of the Main Turkmen Tribes after the Russian Conquest (around 1885)

(Revised June 9, 2010)

Bibliography