Home Page Discussion

The Salon du Tapis d'Orient is a moderated discussion group in the manner of the 19th century salon devoted to oriental rugs and textiles and all aspects of their appreciation. Please include your full name and e-mail address in your posting.

Salon 131: Pictures at an Exhibition: Parsons and Paiwand

by Dinie Gootjes

R. D. Parsons’ Oriental Rugs Volume 3: The Carpets of Afghanistan offers more than the title promises. Besides the rugs, Parsons lovingly describes the country and its people. Not only does the third edition of the book have 154 colour illustrations of carpets, it also contains numerous small black and white pictures of the daily life of the people and the environment in which they live.

The colour plates of rugs are numbered consecutively, as would be expected, but there is a group of pictures with numbers like 39a, 39b etc. The publisher explains in a note: This revised edition contains forty extra colour plates and two new chapters. With the exception of new plates 114-124, which appear in these two chapters, the additional colour is placed in appropriate sections throughout the book and carries a number followed by the letter ‘a’, ‘b’ or ‘c’. Practically all of these letter pictures have two things in common: they are older than many of the other rugs illustrated, and they are published courtesy of Shir Khosrow Paiwand. How did this group of carpets end up in the book?

When R. D. Parsons published the first edition of his book in 1983, he had not been able to find good quality examples of several kinds of rugs described in the text. In the time after the publication of his book he lived in Hong Kong, where he had a rug business. Several of his friends and business relations came back from trips to Islamabad with Afghan rugs of a quality Parsons had not been able to find previously. He ended up also going to Islamabad to meet the provider of those rugs, Shir Khosrow Paiwand, who at that time had a rug business there. In those years of war and upheaval, he had been able to buy old rugs of great quality that now were being offered for sale in the border area between Afghanistan and Pakistan. Here Parsons found many of the kinds of rugs he had not been able to illustrate before. He received permission to photograph the carpets he needed, and that is where the a, b, c and d numbers come from.

The above story, too, is courtesy of Shir Khosrow Paiwand. He later came to Canada, where he and his younger brother Parviz have for many years maintained their Herat rug business in and around Toronto in the province of Ontario. Like good nomads they moved around some, and on December 5, 2009, they opened their new location in Mississauga, in the Greater Toronto Area.

For their Grand Opening they brought out a dozen or so of the rugs illustrated in the book. These rugs have not been shown to the public since the eighties. Natalia Nekrassova, Curator, Collections and Research of the Textile Museum of Toronto was present and gave a short and informal introduction for several of the rugs, pointing out interesting features and giving some background on life in a yurt.

My husband and I were present for the occasion, but I had left my camera at home. After all, why should I want to take pictures of rugs I have available in a book? That was a big mistake. If you thumb through the book, you read tantalizing descriptions in the captions. Green silk and soft blue are mentioned, flecks of gold, pale indigo and yellow from sparak. But when you look through the book, you see red, and not much more. In reality, these rugs showed so many more colours and such a variety of beautiful reds, that I wanted to share some of them here on Turkotek. So I went back the following week, with camera.

For those of you who do not have the book, I will include a full view of every rug, with then some close-ups of special features. I have also taken pictures of a few related rugs that do not appear in the book. Although Herat Carpets is a rug business, all the carpets shown are part of the private Paiwand collection, and are not for sale.

The exhibition consists of the numbers 7a, 20a, 39a & b, 71a & b, 78a, 79a & b, 81a, 93b, 95a and 96a from Parsons’ book. I have selected several of the rugs with which I was most impressed to present here, mainly following the order in which they appear in the book.

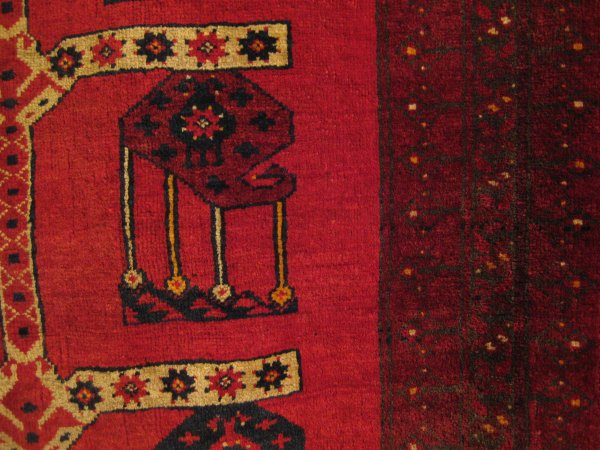

Colour plate 7a is described as An old Taghan juwal, circa 1920, 152 x 97 cm.

The close-up of the gul shows the green silk and the cochineal red mentioned in the text.

Colour plate 20a is described as A semi-antique Beshir rug, circa 1940, 176 x 107 cm.

Ms. Nekrassova mentioned that this form of boteh is rare. It is shown in this Turkotek thread.

It seems likely that it is derived from a velvet ikat pattern. The ground colour is a beautiful deep rose, difficult to capture in a picture. The close-up is not too bad, I think. Mr. Paiwand explained that the name of the colour, rang-i-dokhtar (colour of the maiden), is not so much an indication of a special dye stuff (it could very well be madder), as it is the name of this kind of red: the colour of the wild tulip, the maiden flower.

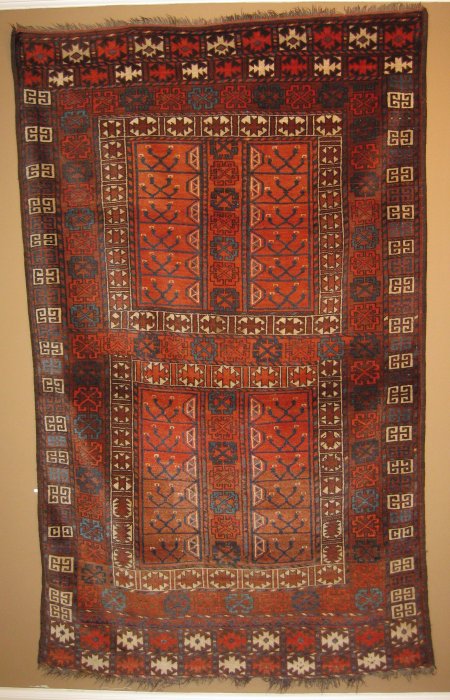

Colour Plate 39a is described as An old Chaii purdah from the Mazar-i-Sherif district, circa 1930, 220 x 130 cm.

This actually is the rug that started the idea of this photo series. It has a great range of lovely colours: blues, blue-green, several brick reds and a soft yellow. This is also the rug that keeps on beating the photographer. There is a beautiful green that refuses to show up on my pictures. Even close-up it only shows itself as medium blue (sorry, I tried).

Colour Plate 39b is described as An old Taghan purdah made in Taghan-Labijar, circa 1920, 210 x 140 cm.

This rug was less shy in showing its true colours. It has a very sumptuous, dark red background with light blue, lighter reds, green and a clear golden yellow. A rich looking carpet, large and imposing as it hung on the wall. I now think that I see a small repaired area in the second picture. But as a whole, one of the striking things in this exhibition is the excellent condition of all the rugs. Full pile everywhere, not even the well known “evenly low pile”, let alone a spot of foundation. The other thing conspicuously missing was any of the kind of orange that makes you clench your teeth. Where something like that shows up on your monitor, just subtract a few degrees of the harshness, then relax the jaw.

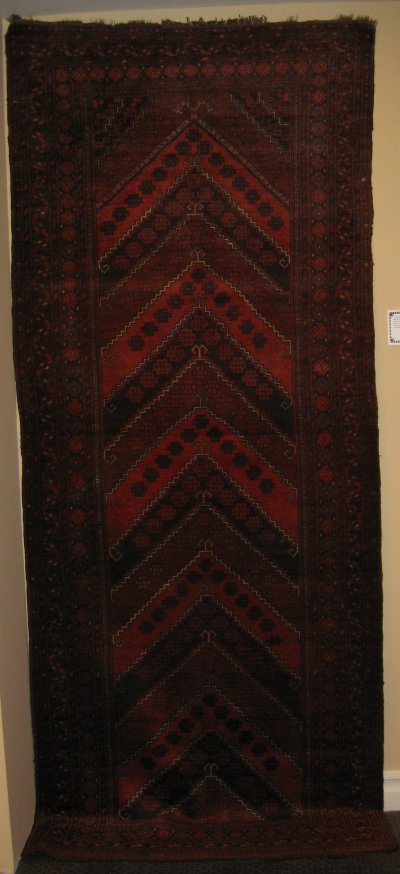

Colour Plate 71a is described as An old Chobash in four panels, early 20th c. 259 x 90 cm.)

Parsons’ overview actually shows up better than mine. But the other picture again shows the variety of colour, with several blues, reds and a nice yellow. The orange is, of course, brick red.

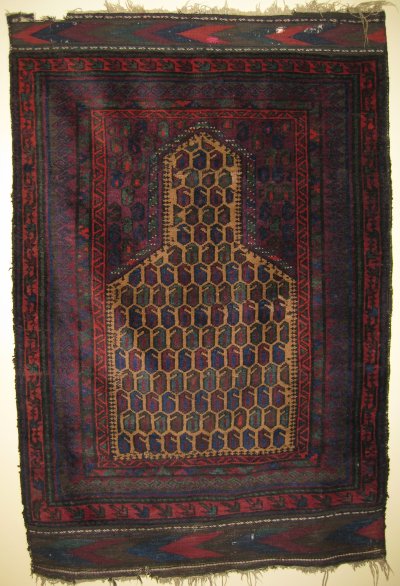

Colour Plate 71b is described as Sheberghan, circa 1935, 276 x 115 cm.

Here again, Parsons’ picture wins from my first one. The second one is somewhat overly bright, but it does show the features Parsons mentions as indicative of the provenance: The weave, incidence of light indigo and the madder rosettes in the border are all indicative of the origin. He wonders whether the weaver set out to make a prayer rug of unusual width, or possibly the piece may have been commissioned.

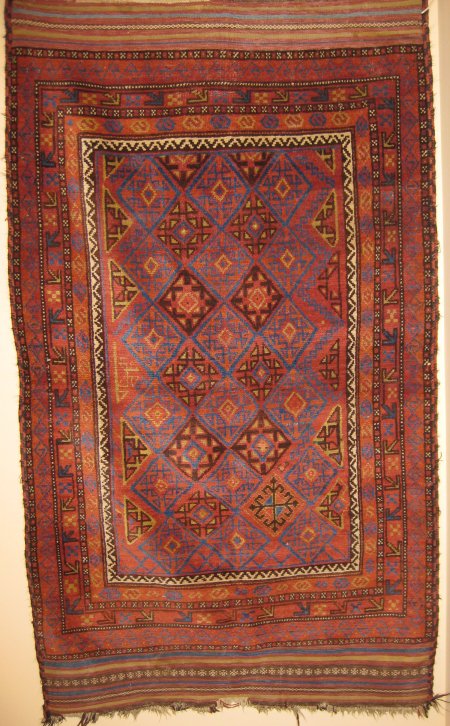

Colour plate 95a is described as An old Farah carpet made in two pieces, late 19th c. 215 x 191 cm.

Here we come to my hands-down favourite. Not the most colourful one, even close up, but the combination of warm brownish red and aubergine tones with the lively cool blues is unbeaten for me. It feels thin and supple. The view of the back shows that the wefts are not severely beaten down at all, often a warp peeks through. It is one of the rugs woven in two strips and later sewn together, as discussed in this archived thread.

This rug also makes an appearance in the second last post, by Chuck Wagner. The last three pictures here show the front and the back of the join. No cut wefts to be seen. Actually, the wefts show up going around the warps on the front of the rug, see the second last picture.

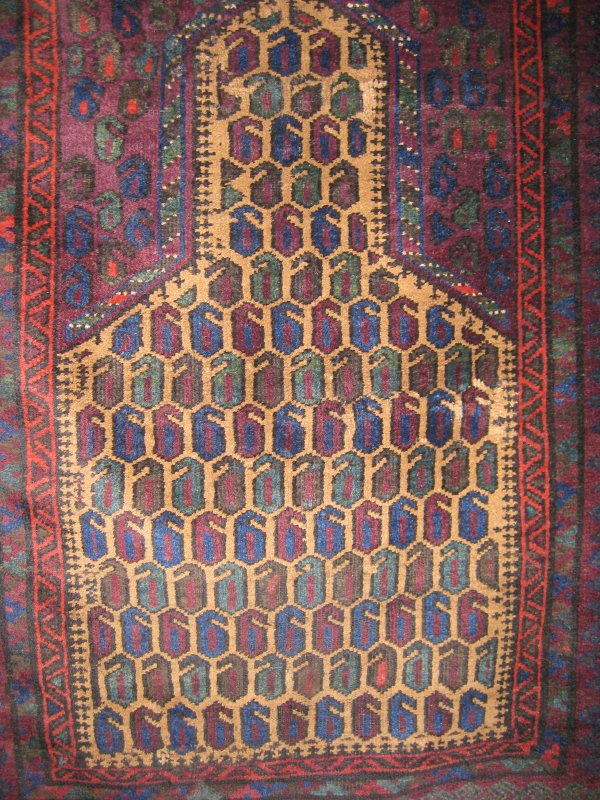

A prayer rug from the same area, which does not appear in Parsons:

Colour plate 96a is described as An old Taimani rug from the Ghor region of west central Afghanistan, circa 1935, 161 x 111cm.

A thin, loose rug. Parsons says that is has a classical weaving structure and the colours that are found in the older Charchaghan kilims, e.g., madder, a soft olive green, indigo, gold and undyed brown wool. The only green I can find here is a few scattered bits in, and at the approximate height of, the second yellow half diamond on the right.

As dessert, two large rugs that I thought did not appear in Parsons. While trying to place them, I found the first one as:

Colour Plate 79a & b, described as An old Taghan carpet made in Labijar, which displays a marked Saltuq influence, 272 x 231 cm.

The second and third pictures show the different kinds of blue, including the light indigo mentioned in the text and the wide goat hair selvedge.

The other one was interesting with the liveliness imparted to the field by the white and yellow dots. I could not find it in the book.

The exhibition continues until the beginning of March, 2010, at Herat Rugs in Mississauga, Ontario. If anyone is in or near Toronto and would like to see these rugs, call 416-920-3680 for an appointment.