Hi all,

Sorry to be getting these images

out on the late side. Meanwhile, the discussion may be passing them by,

but TurkoTek is a forgiving site.

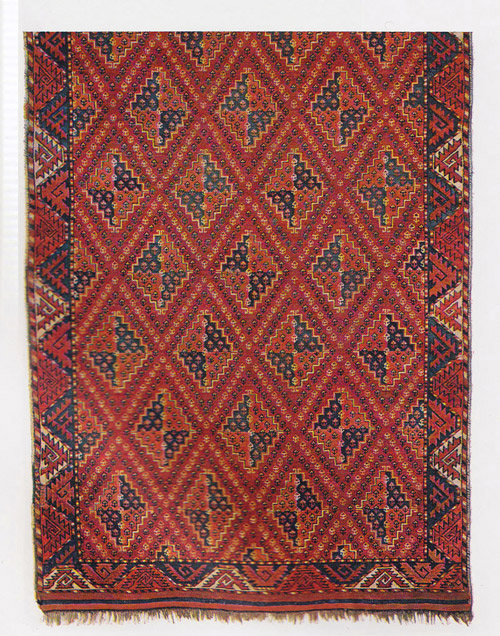

The left hand of the following

images is from Loges, and he says that it is Saryk, not Ersari. He makes

the additional point that the Saryk were related to the Ersari of

Afghanistan. I'm not sure what to make of that, except it supports the

proposition that the distribution of these weaving designs and styles in

the region of Northern Afghanistan/Southern Turkmenistan is a complicated

business. The image on the right is from Tsareva,

Rugs and Carpets from

Central Asia, The Russian Collections (1984). She calls it Ersari,

placing it in the mid-nineteenth century and adding the comment that no

near analogies to it had been found. The two pieces together demonstrate

how different the statement made by the "same" gul can be.

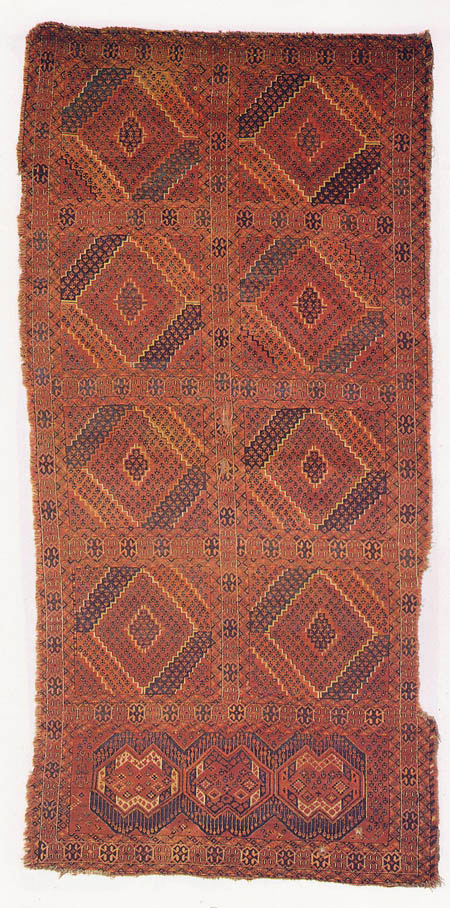

The following pair

are called by Schurmann (left), "Beshir," and by Tsareva (right),

"Ersari," again emphasizing the identity crisis inherent in this group.

Eiland illustrates one of them and comments that "...it seems doubtful the

lozenge figures have any significance as guls." Perhaps not, but the use

of opposing colors in the quartered sections must have some relationship

to the same practice in the drawing of many guls.

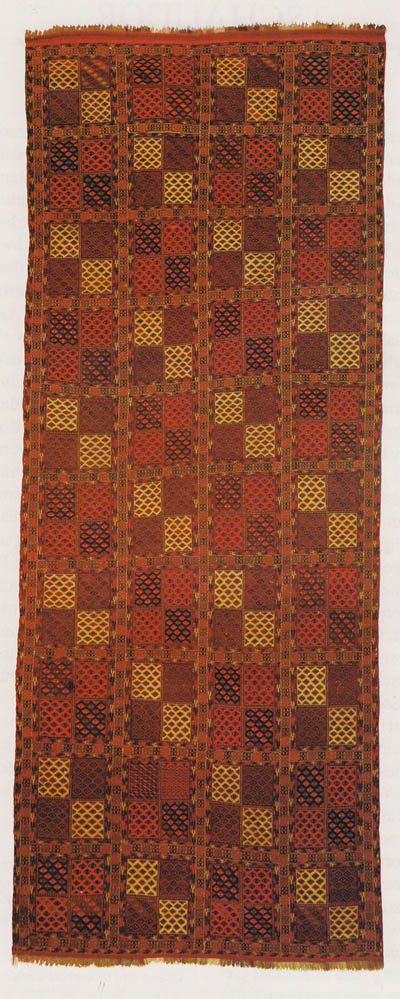

The following example,

from Bausback, 1975, carries the "opposing quarter" concept (as adapted in

this type of Ersari/Beshir) even farther. Rugs of this general type, and

the two preceding, can be seen in late nineteenth and early twentieth

century photos of the region, as mentioned by James Blanchard.

Incidentally, the way the field here is divided into roughly square blocks

is suggestive of the same technique shown in an Afgahn rug from Loges I

posted on February 7. There, the dividing lines employed the

badam

border line. Perhaps the similarity is a coincidence.

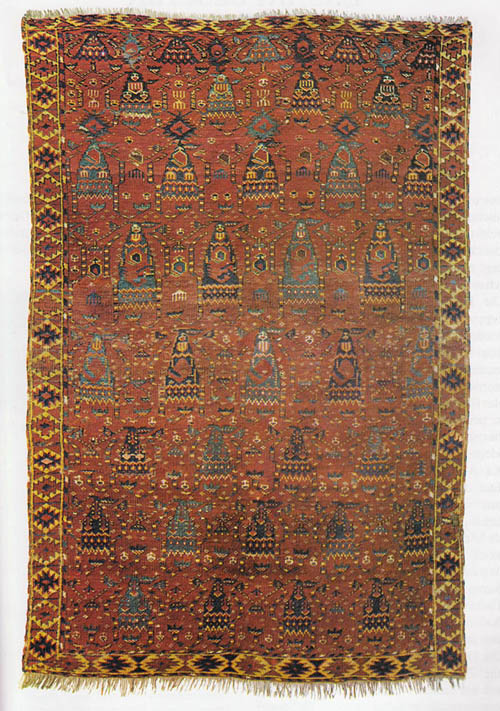

This example,

also from Bausback, is included just to remind us that it isn't

necessarily always about guls.

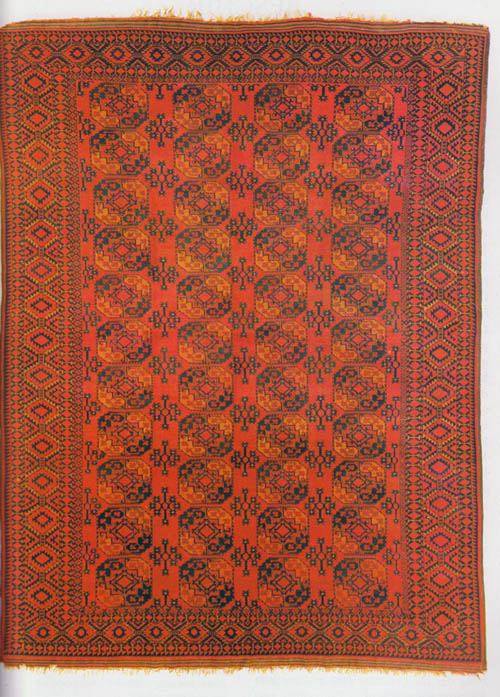

Finally, one more from

Bausback. I include it to exemplify the highly regular, not to say boring

quality of the later-but-not-too-late Afghan Ersaris.

Perhaps it's a

little more bracing in person.

Rich

Larkin