|

Members

Join Date: Oct 2009

Posts: 30

|

No Alum, no party.

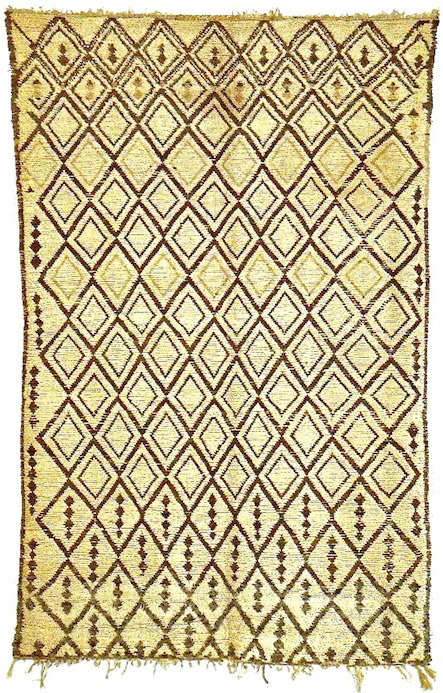

Dear all, Every Turkoteker must be acutely

aware that without Alum, his beloved rug collection would feature mostly

pieces like the one below, said with all due respect for Berber tribes and

brown sheeps.  I would like to share with you

Adam Hart-Davis’ wonderful story of how the wool dyeing industry of

Tudor’s England was saved from bankrupcy. (Mr. Hart-Davis is a British

scientist, author and broadcaster. His well researched and ironic series

have delighted Britons for 40 years.) Taking the Piss-Urine

Through the Ages. By Adam Hart-Davis.In the olden days,

words and expressions for urine seemed to be a common part of the

language: there is a place called Wyre Piddle in Worcestershire, and Lant

Street in South London (lant means stale urine), while in Dorset the River

Piddle flows through Piddletrenthide and Piddlehinton to Puddletown.

Today, however, urine is for some reason unmentionable in polite

conversation, but that does not prevent it from being interesting

stuff.Human urine contains a chemical called urea, which

slowly decomposes to make ammonia, often used as a household cleaning

agent, especially for glass. Ammonia has various useful properties and was

difficult to make before Victorian times; so urine was valuable. Poor

people could sell a bucket of urine for a penny, or half as much again for

redheads. The Roman emperor Vespasian put a tax on the stuff, and

centuries later the pissoirs in Paris were called vespasiennes in his

honour.Urine was used for stiffening the skirts of Roman

soldiers, for preparing raw wool, as a lubricant for wire-drawing, and in

the first gas masks, but perhaps its most spectacular historical use was

in the alum industry that grew up on the coast of North Yorkshire in the

early 1600s.A profitable industry: In Tudor times most

clothes were made from wool, and coloured with natural dyes. The colours

were brighter and longer-lasting if the dyeing was done with a mordant, a

chemical that locks the dyestuff to the fibres of the wool. The best

mordant was alum, and all Europe's alum came from the Tolfa hills, near

Rome—until Henry VIII had a row with the pope because he wanted to divorce

Catherine of Aragon, and the Vatican cut off our supply of

alum.So the hunt was on for alum in Britain. They tried

Alum Chine in Dorset and Alum Bay on the Isle of Wight, to no avail. And

then one Thomas Challoner discovered a way to make it. His recipe was to

dig the grey shale from the cliffs on the North Yorkshire coast, roast it

for nine months over a slow fire, and wash the ashes with water. Then add

buckets of stale urine and warm the mixture, to evaporate the water, until

a fresh chicken's egg just floats to the surface, showing that the

concentration is right. When the mixture is allowed to cool, beautiful

crystals of alum form in the container.At first the urine

was collected locally, and then from Newcastle and Hull, but demand grew,

and eventually it was brought from London, where buckets were left on

street corners, inviting men to contribute. Every week a horse came round

carrying barrels to collect the stuff—like a milk round in reverse —and

the barrels of decomposing urine were taken to the docks and shipped up

the North Sea to Whitby. The story goes that the skippers of these ships,

embarrassed about their cargo, would claim they were carrying wine.

"Rubbish! You're taking the piss..."In spite of this, carrying

urine one way and alum the other was good business for the ship owners.

Vast quantities of urine were needed: in November and December 1612,

16,000 gallons of "country urine" and 13,000 gallons of "London urine"

were taken from Whitby to the alum works at Sandsend, a couple of miles

north. Whitby mariner Luke Fox is documented as having carried 23 tonnes

of urine to Whitby, and returned to London with 29 tonnes of

alum.Astonishingly this alum production business, Britain's

first chemical industry, employed hundreds of men for 250 years, until

synthetic dyes were invented in the 1850s, and you can still see the huge

quarries hacked from the cliffs for 15 miles either side of

Whitby.What amazes me is how anyone worked out the process,

hundreds of years before any real chemistry was understood. Can you

imagine someone saying "There's a nice bit of grey rock. Let's roast it

for nine months and piss on it and see what happens." |