Hi Rich,

Given our current muddle in

trying to sort out what rugdom did/does/should mean by Yuruk, it seems

useful to try to reconstruct a bit of the genealogy of the discourse on

Yuruk rugs.

While Mumford gets it right that the Yuruk are

specifically

Turkic “mountaineers”, his description of their rugs

certainly sounds like those we associate with their Kurdish neighbors,

down to their brown wool warps, “fierce-looking” knotted braids, “peculiar

softness” and lack of symmetry.

G. Griffen Lewis (1913 ) also

lists Yuruk rugs separately from Kurdish (“Mosul”) ones. He cites their

braided warp ends, brown wool warp and, like Mumford, notes that the sides

are often overcast with colored yarns. As to palette, Lewis says that

“brilliant dark colors” prevail, particularly browns and blues. For Mosul

rugs (produced by Kurds around Lake Van) the description is very similar

with a listing of “usually dark, rich blues, yellows, greens, reds and

browns” as the predominant colors.

Here’s the Yuruk from

Lewis:

Hawley (1913),

describes Yuruks as “tribes of Turkoman descent.” He calls their rugs

“entirely distinct” from those woven by any other group in Asia Minor. He

likens them to Kazaks as “in them will be recognized the same long nap,

the same massing of color, the same profusion of latch-hooks, and other

simple designs.” He also mentions that they have adopted some forms from

“the Kurdish tribes to the east.” He may here be referring to Yuruk pile

weavers in central Anatolia. When it comes to describing the rugs woven by

the “Kurds of Asiatic Turkey”, he writes that “brown is very largely used.

There are also dark reds and blues brightened by dashes of white and

yellow. Their “long nap and long shaggy fringe…give these pieces a

semi-barbaric appearance.”

While all three authors clearly believe

there is a recognizable distinction between Turkic Yuruk and Anatolian

Kurdish rugs, it is difficult to get from their descriptions of what those

distinctions consist. In addition, there is no indication of the

geographical location of the Yuruk groups they describe. It is unclear if

any of these Yuruk pile rugs were being produced in eastern Anatolia and

not further west by the Yuncu, Yaghcibedir, or other western Anatolian

Yuruk groups.

Iten-Maritz’s description of the Yuruk

contributes an almost comic note to the confusion by stating “their

carpets do have one feature in common-they all bear the mark of

independence.” This manifests itself in “a rather imprecise, highly

original design,” While Iten-Maritz indicates that Yuruk rugs take on the

character of the locations in which they graze their sheep or reside

during the winter, all of the hyphenated Yuruk types he illustrates are in

either western or central Anatolia. The one possibly useful indicator for

trying to differentiate the pile weavings of Yuruks in eastern Anatolia is

his statement that “the stepped mihrab is common to Yuruks of every

region.” (note the stepped mihrab in picture # 5 in the salon). He

includes one eastern Anatolian rug of this type.

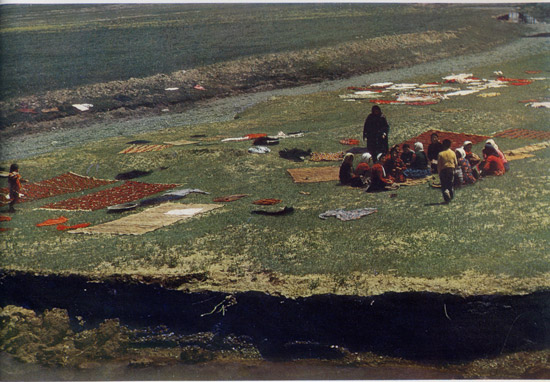

Here's a scene

from Iten-Maritz of Yuruks washing rugs. I can't tell if there are any

pile rugs among them.

Finally there is

Jacobsen (1962) who identifies Yuruk rugs as coming from eastern Turkey

adjacent to Persia. He states that after 1915, Yuruks were only being

produced “in scatter sizes.” He includes a black and white photo of a

“typical non-prayer Yuruk” whose field is a “slight magenta-like red. The

designs are ivory, green salmon and plum.” Writing about the confusion of

Yuruk with Kurdish rugs in 1988, Eagleton says that "dealers in Turkey

have no problem separating the weavings of one group from the other."

Unfortunately, he gives us no guidance on how they make the

distinction.

Here’s Jacobsen’s Yuruk:

And, for a contemporary

touch, here’s a rug listed as Yuruk that was up for auction yesterday in

London:

Joel Greifinger