by R. John Howe

I have never been taken with “Transylvanian” rugs. That’s partly because I didn’t really know

the sorts of pieces that are included, but also because the examples, so

designated, that I have encountered were often uninspiring.

So I went to ICOC XI not disposed to interest in any of the

activities offered that had a “Transylvanian” label. But on one of the early evenings Dennis Marquand reported that he

and his wife had been to a reception at the Sabanci Museum and that the

“Transylvanian” exhibition there was superb. So we paid the 20 YTL for the water-side taxi ride and went.

The exhibition entitled “In Praise of God: Anatolian Rugs in

Transylvanian Churches 1500 - 1750” was, technically, not an ICOC XI event, but

was scheduled to coincide with the days of that conference.

The Sabanci Museum, approached up a steep footpath, provides glimpses of a modern, functional design.

It is situated on a hillside above the Bosphorus.

When we arrived it became apparent (I didn’t read my conference literature closely enough) that there were in fact two textile exhibitions on offer. The “Transylvanian” material was in an upper gallery, with Robert Chenciner’s original Kaitag embroidery exhibition reassembled on a lower floor. We will deal here only with the former.

I have mined what follows mostly from the full-color,

paperback catalog for this exhibition.

It contains not just the exhibition rugs, but a series of articles that

“walk around” some of the relevant literature and issues rather broadly. It is sometimes difficult to keep straight,

as one consults the several articles in this catalog, when the exhibition is

being referred to and when related subjects (sometimes with distant rugs) are

being discussed. I am not a student of

this group of rugs and so invite corrections of what I indicate below. My intent is merely to share some of this

fine exhibition with you.

It appears that a precipitating event for the

“Transylvanian” exhibition was the recent (simultaneous?) publication of a

“new, expanded English-language edition” of Stephan Ionescu’s “Antique Ottoman

Rugs in Transylvania.” It also seems

important that Michael Franses expressed interest in this exhibition and worked

closely on it.

Now, in truth, some of what was in this exhibition has been

treated previously by Hortz Nitz in a recent Turkotek min-salon in which he was

able to effect the participation of Stephan Ionescu himself.

http://www.turkotek.com/mini_salon_00016/salon.html

I have, for that reason, “walked around” some, of what I think were the better pieces in the Sabanci exhibition, that Horst has already shown you from the earlier one in Germany.

The catalog for the Sabanci Museum exhibition includes 37 pile rugs, two Ottoman kilims, seven scholarly articles, heavily footnoted at the end, and a 17-page bibliography.

There is for each rug in the exhibition an attribution, an

estimated date, a size, a provenance, the basic materials of construction, an

indication of its current location, and an associated paragraph that talks

about it. There is no detailed technical

analysis of the pieces in the exhibition.

There are a great many additional images, mostly in full-color, that pepper the articles. If you are even slightly interested in this material, this is a catalog worth having. The ISBN number is 978-975-8362-73-8, Istanbul, 2007.

So, with apologies to Horst for some undoubted redundancy,

what are “Transylvanian” rugs and why should they attract our attention?

Well, first they are defined as a group of rugs woven in

western Anatolia in the 16th, 17th and first half of the

18th centuries. Although

there are definite design subgroups (the catalog says that all of the rugs

presented are “prayer” designs, and there ARE many single and double “niche”

examples), the designs included are far more varied than I had previously

imagined.

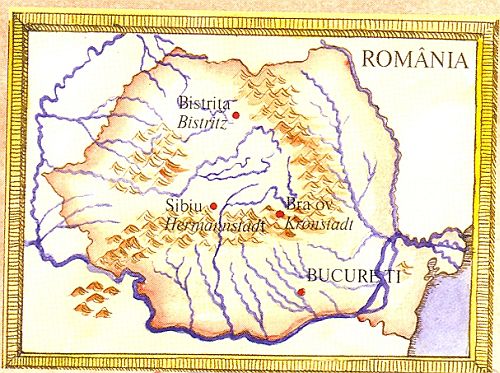

Second, they are a group of rugs woven in Islamic Anatolia,

but bought in, or taken to, a number of places in Eastern European countries,

notably to the “Transylvanian” area of Romania, to decorate evangelical

Protestant churches there, usually of severe Lutheran persuasion.

Third, surprisingly few rugs similar to those in this

“Transylvanian” group, remain today in Turkey.

There are also relatively few in “western” museum collections. So, in a sense, one has to “go” to Transylvania

(and to some Eastern European museums) to see goodly numbers of them.

Part of the task of the catalog is to explain why these some

of these indications are so.

From about the 13th century, Venetian traders had

taken rugs made in western Turkey to Italy and many examples appear in Italian

paintings. But when the Ottomans

consolidated their control over Romania and other Easter European territories

land routes became a second possibility. Despite a degree of remoteness, behind mountain ranges,

the “Transylvanian” area of Romania was placed so that it

was in the path of some of the land trade routes that developed. So rugs made in western Turkey flowed

through Transylvania together with lots of other trade goods.

One of the articles in the catalog highlights Transylvania’s

traditional ethnic diversity, religious toleration and an apparent cultural

sophistication. Reflective of, and

contributing to, the first two factors above was an active recruiting of

European immigrants, in the 12th century, which was answered by

German Protestant Lutherans who called themselves “Saxons.” (It is primarily these Saxon Lutherans who

bought the “Transylvanian” rugs.) A further

factor was the license granted to Transylvanians, after the Ottomans were their

masters, to establish their own political institutions, a remarkably liberal

arrangement, but one that worked to permit the continuation of local tendencies

toward religious and cultural tolerance.

And two economic patterns exposed Transylvanians early to a wide variety

of good from other countries and cultures.

First, Transylvania guilds often defined their clienteles broadly, and

sent their apprentices to other countries and cultures to learn their skills. And Transylvanian cities began as early as

the 14th century granting exclusive trading rights for particular

goods to particular foreign traders. Transylvanians saw and had access to a wide variety of foreign goods.

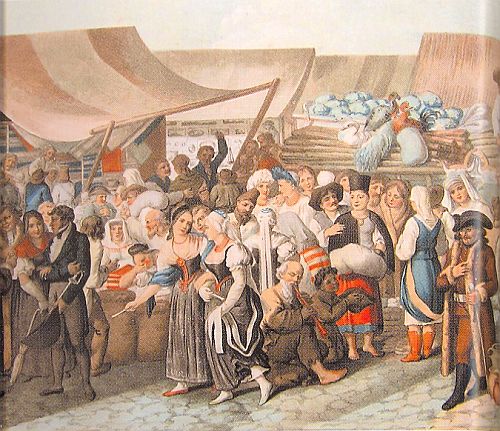

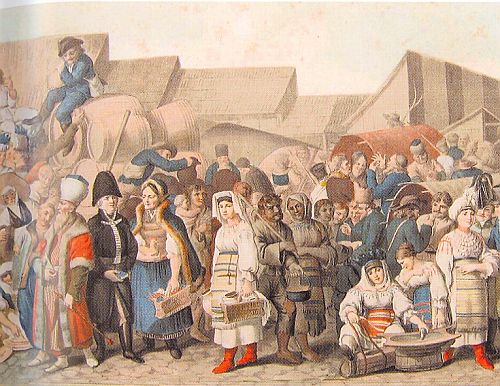

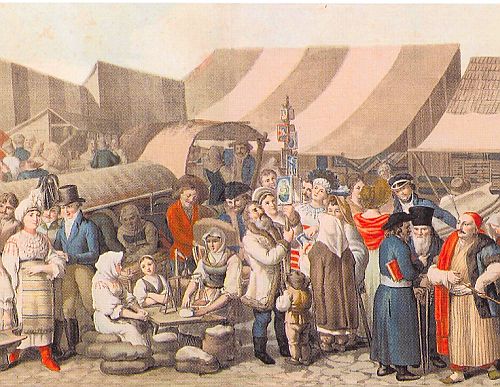

As one entered this exhibition there was an impressive

effort to show graphically, this cultural diversity. A long 19th century mural was reproduced, seemingly

oversized that showed a Transylvanian market scene. Here, immediately below, I have inserted an initial image of this

long mural which is necessarily reduced in size, but I have followed it with a

series of larger detailed images that move from right to left. Look especially at the diversity of costume

which I think the artist uses to suggest a culturally diverse market and

society.

One seeming result of these forces is that wealthy

Transylvanian Protestants, remarkably open to cultural diversity, were exposed

to and bought Anatolian “prayer” rugs and gave them to their churches in

exactly the same way that Muslims did for their mosques (Martie Henze

discovered in Ethiopia that Protestant churches, there, were often the

recipients, on the same basis, of Anatolian kilims and that caches of them

remain there still).

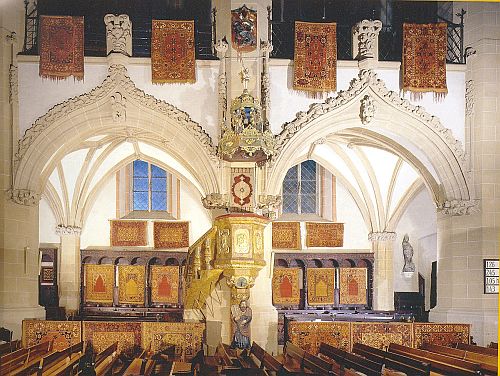

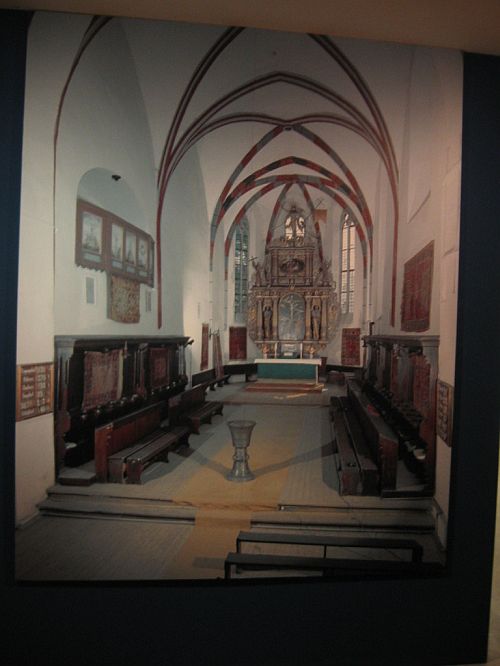

Here is an image of one such Transylvanian church. Notice that it is fortified an indicator

that all was not peaceful and quiet at the time it was built.

One difference seems to be that, in Islamic countries, rugs

donated to the mosques were usually placed on the floor. In Transylvanian churches, donated rugs

tended to be hung on the walls.

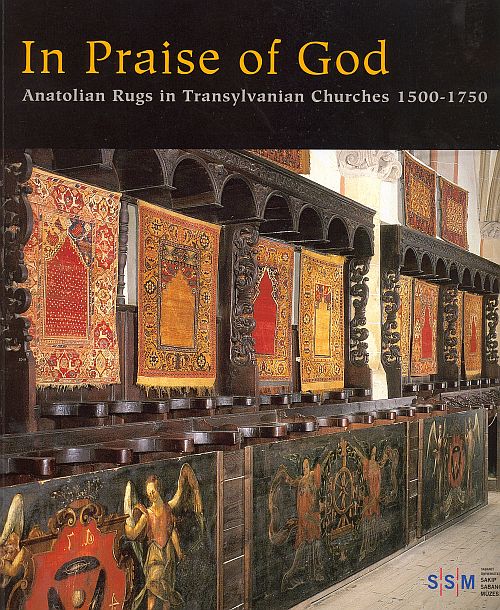

The catalog describes these Lutheran churches of Transylvania as severe, and suggests that these richly decorated and colorful Anatolian rugs were their only items of decoration. That may often have been the case, but notice in the catalog cover photo below, not just the rugs, but the extensive carvings and what seem to be colorfully painted panels.

One of the impressive things about this exhibition was that in one large gallery, the curators created an interior in simulation of those of these Transylvanian, Lutheran churches.

Details of this simulation included an announcing board displaying the numbers of the hymns to be sung during a particular service.

There are nearly 300, purchased and donated, Anatolian rugs

still hanging in these Transylvanian Lutheran churches.