The Salon du Tapis d'Orient is a moderated discussion group in the manner of the 19th century salon devoted to oriental rugs and textiles and all aspects of their appreciation. Please include your full name and e-mail address in your posting.

A Turkotek Digital Field Trip: The Victoria and Albert Museum (Part 3)

by Chuck Wagner

Two beautiful religious vestments are on display adjacent to the Persian carpets. The first is a red silk priest’s vestment, dated 1600-1650, silk pile, wool/metal thread. The silk pile is appears to be knotted in a style similar to that used in carpet construction. It is described as follows on the V&A website: “The famous 'Isfahan cope', an early 17th-century church vestment woven in Isfahan, probably at the expense of Shah 'Abbas the Great, for use in the services of a group of Armenian Christians. This celebrated object shows the figure of the crucified Christ on a ground of scarlet embroidered with the stylised flowers of long-established Islamic convention, attended by the Virgin and St John, while the angel Gabriel - a figure with distinctly Iranian features - hovers nearby. Originally semicircular, worn as a cape.”

Nearby, this Orthodox vestment is on display, described as lampas weave silk and dated 1650-1700, with some delightful pastel tones:

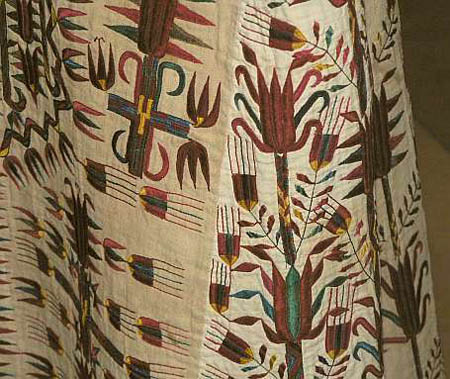

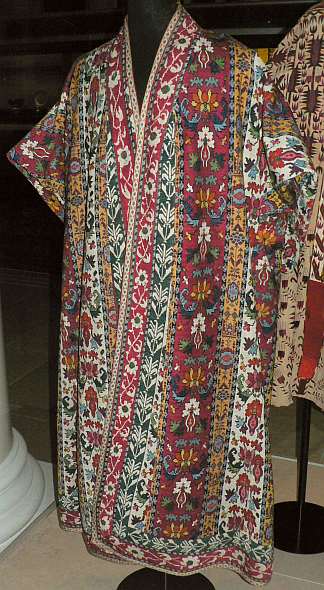

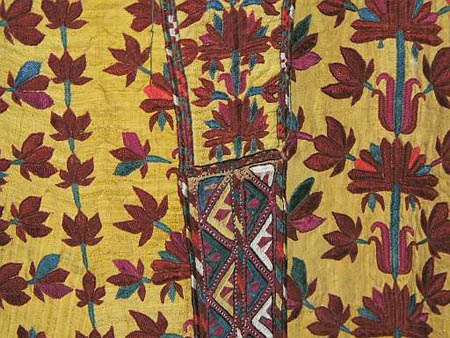

In the front left area of the gallery is a small case with several nice examples of Central Asian chyrpys and chapans, and is one of my favorite displays. The white chyrpy is dated 1900-1920; the embroidered cross-stitch chapan, 1850-1900; and the yellow chyrpy, about 1850.

The final piece in this article is from the South Asian (read: India) gallery, which is probably worthy of another salon all by itself. This is the Fremlin carpet, a Mughal carpet, the provenance of which is quite well documented. This image of the full piece is from the V&A website:

Some detail from the lower right side:

There is some interesting reading available on the V&A website:

“The Fremlin Carpet is among the most impressive of those many works in the Museum’s collection made by Indian craftsmen for members of the British trading and administrative community, particularly those working for the East India Company.”

“This stunning Mughal carpet is named after William Fremlin, an official of the East India Company who became president of the Council at Surat. He commissioned it during his service in India from 1626 to 1644. It is one of only three Mughal carpets with British coats of arms known to have survived: a second was commissioned in Lahore in 1631 for the Girdlers Company in London, and a third (known only by repute) was apparently commissioned by Sir Thomas Roe, James I’s ambassador to the Mughal court fron 1615 to 1619.”

”The design of the Fremlin carpet is based on a standard type of animal or ‘hunting’ carpet which derives from Persian prototypes, although it is unmistakably Indian in the drawing and colouring of its lifelike figures, flora, and scenes of fierce tigers attacking prey. The carpet would have been made to be spread over a table, which was the normal usage of carpets in England at that time, rather than on the floor as it would have been in India. Considered Spanish in 1882, this carpet was not alone in being misidentified at that time: Indian carpets were frequently called Persian, or at best labelled ‘Indo-Persian’ and considered a provincial offshoot of Persian carpet weaving, until they were studied in their own right in the twentieth century. (The Fremlin Carpet was bought in Paris in 1936.)”

”Controversy over the provenance and dating of Mughal carpets has arisen mainly through the lack of documented examples, which is why pieces such as the Fremlin Carpet, traceable to a certain owner at a fairly secure date, have become key objects in this field of study. Although it is known that fine carpets were being made in Agra and Lahore (both at times capitals of the Mughal Empire) since the late sixteenth century, there is very little evidence to link specific carpets to either centre. The link with Lahore for the Fremlin Carpet is based on the provenance of the related Girdlers Carpet and also on references to Lahore in the labels on contemporaneous Mughal carpets still in the palace at Jaipur. Although William Fremlin is known to have been stationed in Agra in 1630 and 1633, he is unlikely to have commissioned such a grand object for himself until after he attained the rank of president in 1637.”

I would recommend this venue to anyone traveling to London; the V&A is a visitor friendly facility with a marvelous variety of materials on exhibit, including many carpets and textiles not pictured here, and lots more. That said, one thing that struck me as a little odd is the complete lack of any tribal pieces on display in the Islamic gallery. So if you’re not interested in workshop carpets, you may want to moderate your expectations accordingly.

Some additional reading on the topic of 16th and 17th century Persian carpets can be found on the Turkotek site at: Classical 16th-17th Century Persian Rug Fragments at the TM