by Horst Nitz

"When I was seventeen, it was a very good year", sung The Kingston Trio from the radio in the dashboard, and I wholeheartedly agreed. Now I was eighteen, and it was an even better year. The summer of 1966 saw me in a small band of friends roving the higher latitudes of Scandinavia in an old Volkswagen Beetle, enjoying life under the midnight sun and the company of nice Finnish girls. No thoughts of rugs at this time. But I had been working on it. The year before, in Belgrade, I had acquired my first kelim.

Back home Hannah Erdmann was

pulling loose ends together of unfinished works and was writing the

foreword to a posthumous publication of her husband Kurt Erdmann,

former director of the Islamic Arts Department at the "Dahlem Museum"

as it was called, in Berlin (West-). The book was published in the

autumn (Erdmann K, 1966, Siebenhundert Jahre Orientteppich,.

Busse Verlag, Herford; English Edition: 1970, Seven Hundred

Years of Oriental Carpets. Faber & Faber, London).

It includes a chapter in which Erdmann undertakes a survey of the stock

of oriental carpets in both Germanys that had survived WW II - not an

inappropriate undertaking although it being twenty years after the war

by now, considering that the Berlin Wall had been up only a few years,

and cold war was going through an especially frosty period, restricting

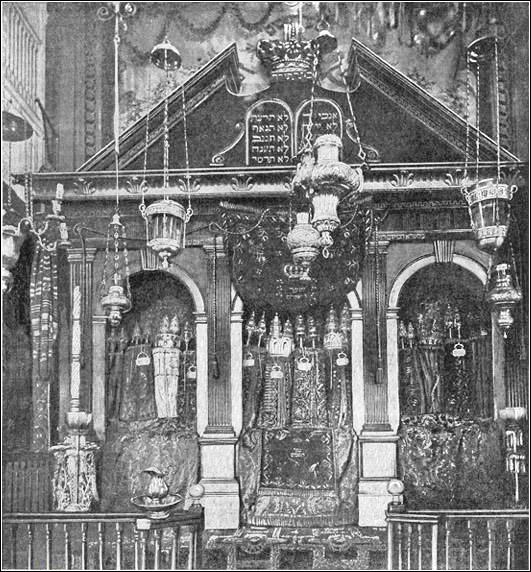

contact on most levels. One of the most outstanding pieces in this

survey was the so-called "Synagogue Rug" in the Pergamon Museum in the

East, being one of the oldest rugs in existence, being the oldest

Spanish rug, dating to the 14th century or earlier and being the one

and only known rug with a Torah Shrine motive. Before it was acquired

for the museum by its founder Wilhelm Bode in 1880, it allegedly was

kept in a Church in Tyrol/Austria. One wonders how it got there. A full

account of it has been given by Friedrich Sarre, former director of the

Islamic Art Department of the Berlin Museum (Sarre, F. &

Flemming, E., 1930, A Fourteenth-Century Spanish Synagogue Carpet. The

Burlington Magazine for Connoisseurs, Vol. 56, pp 89-95).

The rug is still there and open to visitors in the redecorated

exhibition rooms of the Pergamon Museum in Berlin, now hosting the

reunited collections of both former Islamic Arts Departments.

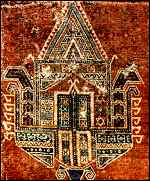

The design represents a tree, from which rather thin stem branches

spring off on either side, terminating in oversized blossoms, each

representing a Torah Shrine.

01 The "Synagogue" Carpet, 303 x 94 cm, upper

third

02 Detail

I quote from the early description by Wilhelm Bode in his "Handbook" (Bode, W., 1902, Vorderasiatische Knüpfteppiche, Leipzig). These (blossoms) are of a remarkable form. In the centre is a closed door surmounted by a pyramid; on either side is a hook-like leaf, much conventionalised, and angular in its outline; the interior of these figures is filled with a variety of small birds, stars, zigzag lines and similar ornamentation.” The border according to Sarre contains purely decorative Kufic characters meaningless in themselves. Bode refers to the peculiar method of knotting - unlike any other Oriental carpets - discussed in detail in the mentioned article by Sarre & Flemming and which gave rise to the term "Spanish Knot" (see below). In the form of the blossoms growing from the branches of the "Tree of Life", Sarre and Flemming perceive a decorative rendering of the Jewish "Ark of the Law": "The Aron-Ha-Kodesch", or holy shrine, which was (is) affixed to the chief wall of the synagogue, and contained (contains) the Rolls of the Law, enjoyed from remote antiquity the profoundest veneration. It always has the same form - a rectangular chest with double doors - each with four recessed panels - surmounted by a rectangular gable-end.

A full-size coloured image of

the rug is depicted as plate 91 in Felton, A., 1997, Jewish

Carpets, London.

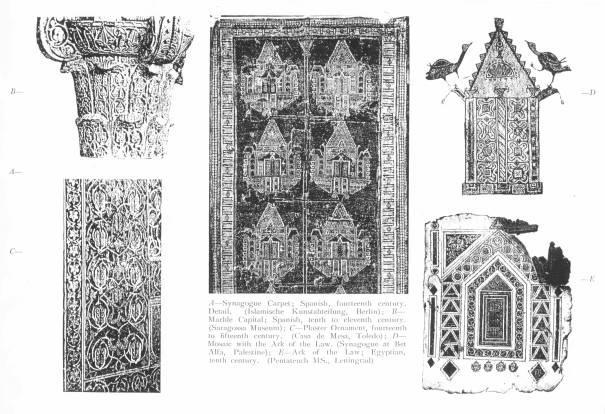

The authors support their interpretation by relating the design to

similar representations in architecture and decorative arts of the

period, as well as to historic predecessors: the decorative marble

slabs on the Great Mosque at Cordova (10th c.); a 10th or 11th century

capital in the museum in Saragossa (B); a stucco ornament from the Casa

de Mesa in Toledo, 14th or 15th c. (C); the mosaic pavement of the

ancient synagogue at Bet Alfa in Palestine (D); on a door-post in the

ruins of the synagogue at Tel Hûm, the ancient Capernaum; on

figured gilt-glasses of the first centuries of our era (F); a picture

of the Ark from a Pentateuch manuscript, presumably Egyptian of the

middle of the tenth century, preserved in the State Library at St.

Petersburg (E):

03

images of similar

designs A - E

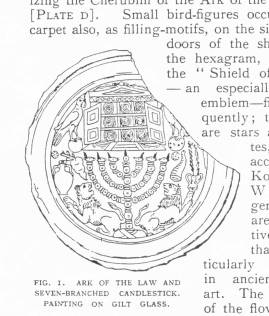

04 gilt glass F

A few amendments on the observations and conclusion by Bode and Sarre

seem appropriate.

It is a characteristic of the design of nearly all representations of

the shrine that usually two or even three pentagonal constructions are

boxed into one an other, as in the case of the carpet and the

Pentateuch. As said, the Torah Shrine invariably comes with a

pentagonal outline, many synagogues seem to have picked up this shape

and show a pentagonal facade themselves, in this way demonstrating the

principle. There also appears to be some confusion as to the

significance of the Torah Shrine vs. The Ark of the Law or Ark of

Covenant; the terms seem to be used interchangeably. The Torah Shrine

is the most sacred space in any synagogue up to the present day. In it

the Torah Rolls are kept from which members of the community read to

the assembly. Usually the Torah Rolls are concealed from view by

curtains. I don't know of any instance where a carpet has taken this

function. Neither do doors seem to be a regular feature. On the other

hand, not being a Jew myself, I have not seen many synagogues from the

inside. The Torah Shrine on the gilt glass, looking much like a mixture

of a cupboard and a temple, clearly contains objects that allow being

associated with Torah Rolls. However, there are no rolls on the other

images and, possibly, what looks like doors on them may really be

something quite different.

The gilt glass dates to the 1st century AD, which is quite early in

terms of the history of Torah Shrine as such. The representations on

the rug and the Pentateuch and the Bet Alfa mosaic appear to stand in a

much older tradition: that of the Ark of Covenant (5. Mos. 10, 1 ff).

It has been suggested that the Torah Shrine is not the direct successor

of the Ark of Covenant, after its disappearance from history in 6th

century BC, although containing the Torah Rolls in much the same way as

the stone tablets inscribed with the Ten Commandments were kept in the

Ark, but the successor of the Second Temple. This could be the

explanation for the "box principle" referred to before: in the

synagogue (outer pentagonal box or shell) the Torah Shrine (second

box/shell) modelled on the facade of the Temple (third box/shell), in

it a representation of the Ark with two stone tablets inscribed with

the Ten Commandments.

There may be another reading of the box principle. According to an

entry in www.JewishEncyclopedia.com

in the

Rabbinical literature it is

recorded "that Bezaeel made three arks which he put inside of one

another. The outside and inside ones were made of gold ... while

the middle one was of wood." This shows what it may have

looked

like in the fantasy of a later artist:

05 the Ark carried into the temple

(Wikipedia)

The following images show representations of the stone tablets in different contexts:

06

in

the Torah Shrine gable of an old synagogue, possibly Gibralter

07 on the facade of the Baroque

synagogue of Lesko (Poland)

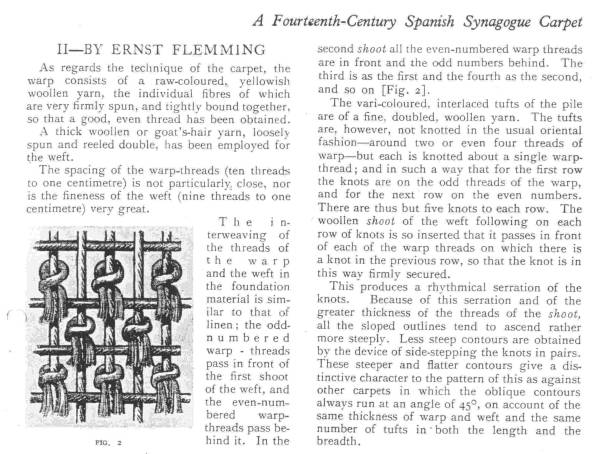

In the following part II of the

original article, Ernst Flemming discusses the peculiar technique in

which the carpet was being made (scan from the original article):

08 II Spanish Knot by Ernst Flemming

In the preparations for the "ORIENT" exhibition some years ago, the

carpet had undergone restoration. Like some other early carpets, i.e.

the "Ardabil" in the V & A (Victoria and Albert Museum) in

London, it had been assembled from fragments of the same rug. This and

other flaws had been put right in the course of restoration, slightly

altering the carpet's measures.