Posted by Filiberto Boncompagni on 06-03-2006 11:18 AM:

Avar connection?

Hi Horst,

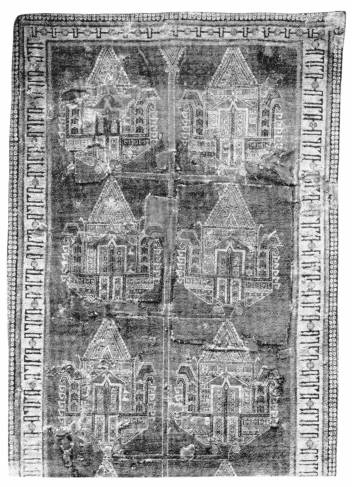

You say that you did not see any design related to the Sinagogue Rug among Avar

rugs.

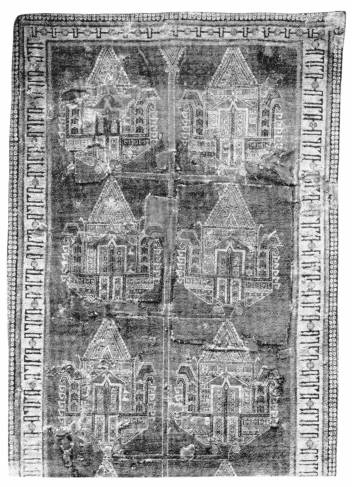

I wonder if you are aware of this kind of design in what are commonly believed

to be Avar Kilims:

I copied also the Synagogue Rug for better comparison.

Notice that, in my opinion, a possible “Avar connection” doesn’t exclude at

all the plausibility of your theory.

Regards,

Filiberto

Posted by Horst Nitz on 06-03-2006 05:13 PM:

Hello Filiberto,

it seems, the Ark motive has meandered throughout the eastern Trans-Caucasus

and can be held responsible for many floral and some zoomorphic motives, such

as in the “Avar”-Kelims you are showing us. The echo is very faint though in

this particular case. I doubt, very many would have seen a connection between

those kelims and what Doris Eder / Ian Bennett hold to be an “Avar Throne” before

this Salon – both authors evidently had the pile rugs (“Tachte Shirvan”) in

mind, not the kelims, whose motive is obviously floral and much conventionalised.

In my personal “nomenclature” this would suggest they are a later form - art

historically, not age-wise, although the latter might also be correct.

There exists a substantial number of fine Daghestan rugs, especially in the

group with a lace design, with the late floral form of the Ark, some dating

to early 19th century. The “Avar”- Kelims, if this is what they are, may have

been modelled on those. They appear to be the interpretation, not the original.

Many rugs with a lace design (not all though), this seems worth mentioning,

display the Ark turned 180°, thus the gable motive (those “beagle-ears”) becoming

the leaves flanking the upright pod or blossom. A particularly pretty rug demonstrating

the principle (without a lace in this particular case) is plate 388, a white

18th century Kuba-Seichur in the Eder / Bennett book which I trust you have

on your shelf (have a look at some of those red blossom motives). Does it dawn

on you? We are looking at something that could be called a late Shield-Rug -

possibly with an interpretation of the Ark in the middle of it!

Looking at the "modern" blossom-like Torah Shrine motive on the Synagogue Carpet

("modern" from a 15th century perspectice) and visually blending it with the

ancient "ark"- motive of plate 09 and 10, I can see much of what makes those

16th century shield carpets, the pronounced gable or fork in the "ark"- motive

transferring into the protective palmettes.

Regards,

Horst

Posted by Filiberto Boncompagni on 06-04-2006 06:03 AM:

Hi Horst,

About Avar Kilims being interpretations of motifs from knotted rugs, I have

a few doubts and caveats.

First, the weavers in the highlands of Daghestan weren’t exposed to commercialization

like in other parts of Caucasus, while they had a long tradition of producing

their “davaghins” (or “dums” for the Kumyks) - i.e. the long kilims posted above

- for their own use.

For this reasons it’s more likely that they used their traditional patterns.

These kilims can be quite old too, given the habit of hanging them to the walls

of the highlanders' houses.

I met in person a “davaghin”, one of those with Fachralo-like medallions, it

was dated 1863 and in very good conditions for its age. It was presented in

a Show and Tell thread last year, together with a bunch of similar examples

(showing also the same age) found on the Web. Were the medallions copied from

a Fachralo or it was the other way around? 1863 was rather a pre-commercial

period for the Caucasus or am I wrong?

As Paul Ramsey wrote in his article in Hali 89, 1996 “The Dragon Dums of Daghestan”:

Daghestan dums are weaving of highly local, regional character, as evidenced

by their apparently unique structure and distinctive palette.

…

Other types of Daghestan kilims furnish further evidence of influence from classical

carpets, but it remains unclear exactly how these influences – and specifically

the dragon designs – were transmitted from urban workshops to the villages of

the northeastern Caucasus.

Regards,

Filiberto

Posted by Horst Nitz on 06-07-2006 05:14 AM:

Hi Filiberto

This is an Avar felt from a Würzburg/Germany gallery website:

Additional information is: Northern Caucasus, ca. 1900.

The combination of red and blue and an otherwise limited pallette seems to be

typical for Avar rugs; now we are discussing them it comes back to me that the

one I had seen about half a year ago on ebay, also displayed the same limited

range.

Regards,

Horst

Posted by Filiberto Boncompagni on 06-07-2006 06:47 AM:

Hi Horst,

That image is really familiar. It was already posted in an archived discussion:

Avar/Daghestani Felt Rugs.

Read that discussion please. Taking into account the felts from Daghestan is

going to complicate further the matter. I would opt for considering them only

as a collateral source of design, though.

Regards,

Filiberto

Posted by Filiberto Boncompagni on 06-10-2006 06:36 AM:

Hi Horst,

quote:

I would accept it as an interpretation of the ark design. It's an interesting

one, also drawing from the Avar kelim design apparently.

…

Has a date been given?

As the post with the picture in question has been transferred to the “Shield”

thread,

I copy it again here, otherwise your remarks quoted above don’t make sense:

This is a scan from Chirkov “Daghestan Decorative Art” 1971, page 257:

The rug is said to be “Lezgian work, 19th century.”

Now, about your comment

quote:

The combination of red and blue and an otherwise limited pallette seems to be

typical for Avar rugs

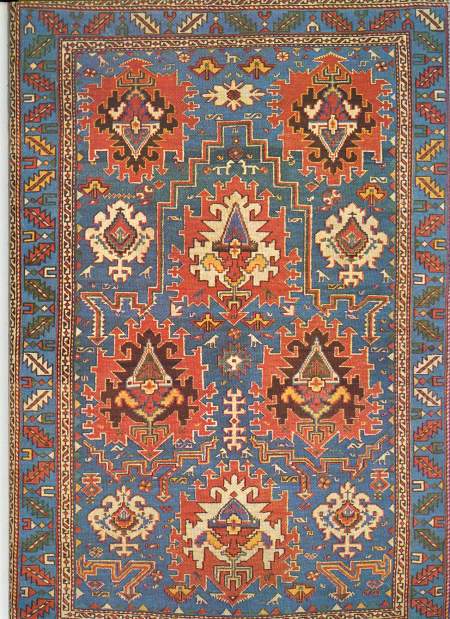

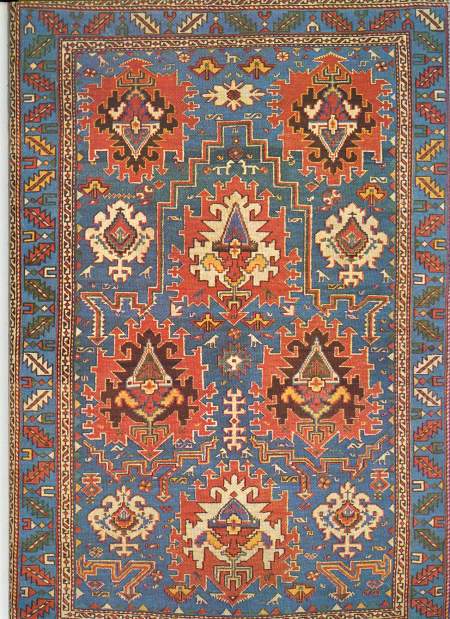

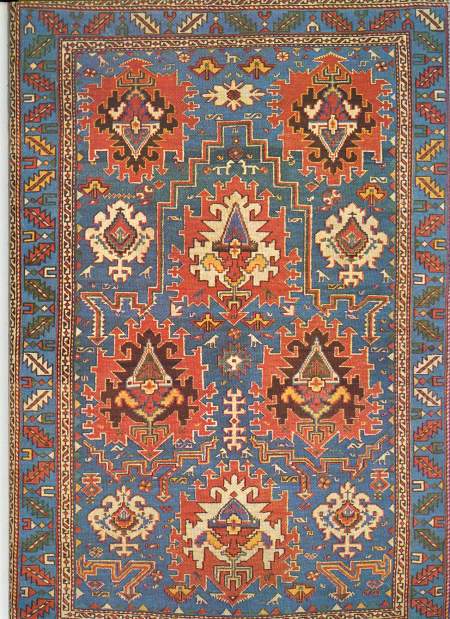

I agree, especially if we consider this Avar rug:

The oddity of this pile rug is that it seems clearly inspired from a felt rug

but not in a direct way. I mean the rounded design of the felt could be quite

easily been rendered in the pile technique. Why the weaver translated it in such

an angular form? The only explanation I can offer is that the design was first

transferred on a flatweave. The limits of that technique obliged the pattern to

become angular, and only then was re-copied on a piled rug.

For flatweave I don’t mean only Kilim.

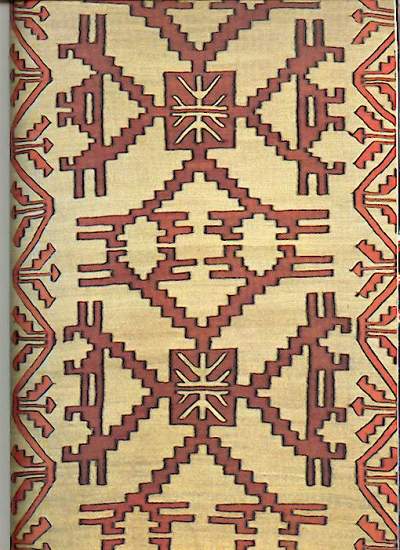

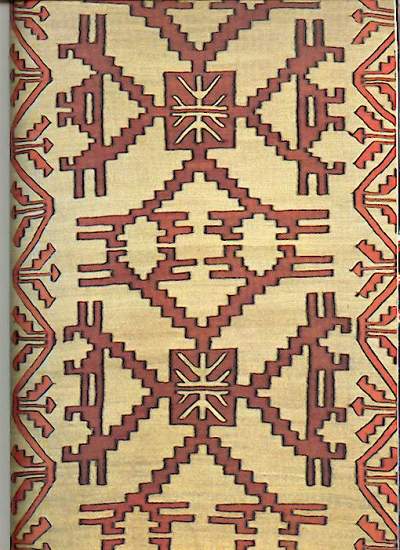

This is a “chibta” i.e. a mat made with wool on sedge fibers - from D. Tchirkov’s

“Daghestan decorative art”:

There are four examples in Chirkov’s book, all of Avar make. (The book presents

is also an example of felt similar to the one above, but with blue design on red

background, also of Avar make).

Here there’s another chibta I met in person last year:

Notice the similarities between the borders on the chibtas and the minor

borders on the first and third kilim at the beginning of this thread.

Let’s go back to this Lesghi rug:

Chirkov makes an interesting observation about this design: “The napped carpet

technique reflected ornamental motifs closed to the “many-necked” Avar davaghins”

The “many-necked house” is the most known motif in the repertory of Avars and

Kumyks (it has to be said that both used to weave the same kind of kilims, so

we should refer to them as Avar-Kumik, albeit Peter F. Stone prefers Kumik-Avar

– anyway, for practicality I’ll stick to Avar only).

I’m going to borrow from Marla Mallett’s website, in particular from the article

Tracking the Archetipe - Technique-Generated Designs and their Mutant

Offspring

A couple of images with her comment:

The Avar kilim at the right

and the Avar knotted carpet below

both have kilim features; both also have knotted carpet characteristics. So which

is closest to the original form? Although both are dramatic pieces, the kilim

exemplifies an unnatural, contrived tapestry expression. It is primarily linear

and vertical in its patterning, with multiple rows of endless tiny crenellations.

In my opinion, the general character of these pieces evolved in knotted pile.

The kilim is a copy of a knotted-pile carpet rendition of a kilim design.

I draw your attention to the motif of the knotted-pile rug. Isn’t that a stepped

roof or gable? The “necks” looks suspiciously like birds too.

Could this design be a derivative (and duplicated-mirrored) version of the Synagogue

blossom? Perhaps a different version of the “shields” shown by the first three

kilims of this thread?

Visually, this could be the path to the “many-necked house”:

Regards,

Filiberto

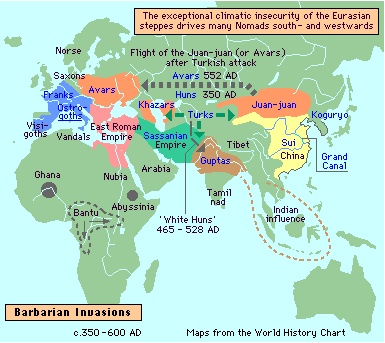

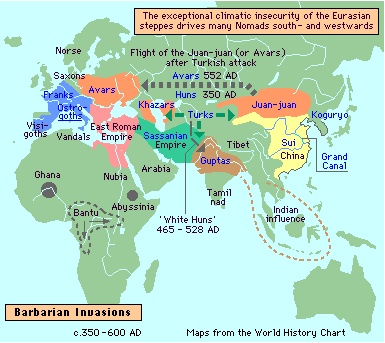

Posted by Horst Nitz on 06-19-2006 06:35 AM:

Hi Filiberto,

as a context information, the following (links) may be useful.

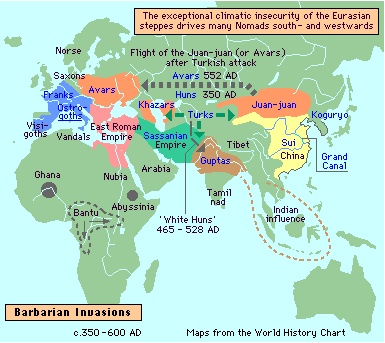

A v a r s (known as Obri in Rus’ chronicles and Abaroi or Varchonitai in Byzantine

sources). A large union of Turkic tribes. The Avars appeared in the steppes

west of the Caspian Sea in the middle of the 6th century AD. After moving westward

through the territories of today's Ukraine, they stopped for a time in the region

north of the Black Sea. Here they persuaded the Alans and Ugrians to join their

alliance. In the 560s on their way to the middle Danube River the Avars and

their allies invaded the territory of the Antes. The Avars conquered and brought

into their alliance a number of Slavic tribes. At the end of the 560s they established

a khaganate on the middle Danube with a capital in Pannonia. From there the

Avars made successful raids on the Slavs, Franks, Lombards, and Byzantium. As

a result they controlled the territories from the Elbe River to Transcaucasia

and from the Don River to the Adriatic Sea. The empire, however, lacked any

organic political or economic unity, and when the Avars suffered a crushing

defeat at Constantinople in 626, a series of revolts began among the subjugated

tribes. The most important uprising—the uprising of the western Slavs—was led

by Samo, and resulted in the founding of a Slavic state on the territory of

present-day Czech Republic and Slovakia. The rise of the Bulgarian Kingdom in

680 and the victory of Charlemagne in 797 put an end to the Avar empire.

(from Encyclopedia Ukrainia)

(image of the moves of the “old” Avar from http://www.hyperhistory.com/)

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Caucasian_Avars

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Eurasian_Avars

Whether present day Caucasian Avar are divided from the “old” Avar by time or

language or genes or all of it, their felt coverings unmistakably seem to breath

the memory of the steppes and pastures of central Asia (of all the rugs I know,

they resemble most closely some of the nomadic kelims from the Baliksehir and

the Antalya regions in Turkey by colour schema and general appearance - but

please, let's not discuss this here and now). They seem to be an authentic ‘weave’.

The Avar kelims on the other hand seem to recrute from several sources: colour

schema from the felts, some design pattern like those rather awkward looking

‘fish-spears’ stylised almost beyond recognition also from the felts (please

notice what lovely ranks and blossoms they still are on those felts); highly

stylised blossoms (if that is what they are) possibly derived from Daghestan

area pile rugs that utilized a floral rendering of the ark (often turned 180°)

as a field motive; shield motive from anywhere, it apparently being one of the

most widely distributed kelim motives in the eastern Caucasus and across the

southern border (possibly related to one of the main motives in those dragon

carpets). Besides aesthetic wants, those blossoms faintly resemble the ark motive

in the Synagogue carpet, be it chance or not. A religious significance in it

seems unlikely, the Avar being Sunnite Muslim.

The Lesghi rug plays in a different aesthetic league, it echoes the ark that

has been put onto or before a shield in this instance, also accommodating the

obligatory birds, all not unlike in the well known shield carpets.

Referring to the piled Avar rug you were saying: “I draw your attention to the

motif of the knotted-pile rug. Isn’t that a stepped roof or gable? The “necks”

looks suspiciously like birds too.”

It may have been a stepped roof or gable a long time ago; those ‘necks’ or ‘birds’

look as much like birds as they look in some Turkoman designs - to my shame

I have to admit, I was never able to decide whether I should think of that interpretation

as highly stylised or far-fetched.

Regards,

Horst

Posted by Filiberto Boncompagni on 06-19-2006 07:38 AM:

Hi Horst,

Quod erat demonstrandum is that design transfer doesn’t happens only

in a linear way but - and most often - from different sources and mediums.

The result is that we can find echoes of ancient motives (if I’m right about

the “many-necked house”) or more direct renditions in textiles of the same age

and almost of the same provenance.

Regards,

Filiberto

Posted by Filiberto Boncompagni on 06-19-2006 08:00 AM:

Another clue to the possibility that the “many-necked house” could be a rendition

of the “Synagogue blossom” is just semantic.

For a highlander, “many-necked house” could be an effective description of the

synagogue motif too, don’t you think?

Regards,

Filiberto

Posted by Horst Nitz on 06-19-2006 04:30 PM:

Hi Filiberto

I suppose one could call it a ’many-necked house’ if one includes the whole

of the blossom and not alone the ark motive in the perception. It is an odd

label though and I wonder where Tchirkov got this idea from, what house, who’s

necks? It can’t mean an apartment block with everybody peeping out of the open

window?

You are asking: “For a highlander, “many-necked house” could be an effective

description of the synagogue motif too, don’t you think?” This is the link to

the highest village in Azerbaidjanian Caucasus, perhaps they would know?

http://www.xinaliq.com/

Regards,

Horst

Posted by Filiberto Boncompagni on 06-20-2006 03:09 AM:

quote:

It is an odd label though and I wonder where Tchirkov got this idea from

I haven’t the slightest idea… Nor I know about Chirkov’s credentials and titles

(an art scholar? An ethnographer?) The book doesn’t say.

Unfortunately this is the only known source about Daghestan decorative art, as

far as I know.

Regards,

Filiberto

Posted by Unregistered on 07-02-2006 10:18 PM:

quote:

Originally posted by Horst Nitz

Hi Filiberto,

as a context information, the following (links) may be useful.

A v a r s (known as Obri in Rus’ chronicles and Abaroi or Varchonitai in Byzantine

sources). A large union of Turkic tribes. The Avars appeared in the steppes

west of the Caspian Sea in the middle of the 6th century AD. After moving westward

through the territories of today's Ukraine, they stopped for a time in the region

north of the Black Sea. Here they persuaded the Alans and Ugrians to join their

alliance. In the 560s on their way to the middle Danube River the Avars and

their allies invaded the territory of the Antes. The Avars conquered and brought

into their alliance a number of Slavic tribes. At the end of the 560s they established

a khaganate on the middle Danube with a capital in Pannonia. From there the

Avars made successful raids on the Slavs, Franks, Lombards, and Byzantium. As

a result they controlled the territories from the Elbe River to Transcaucasia

and from the Don River to the Adriatic Sea. The empire, however, lacked any

organic political or economic unity, and when the Avars suffered a crushing

defeat at Constantinople in 626, a series of revolts began among the subjugated

tribes. The most important uprising—the uprising of the western Slavs—was led

by Samo, and resulted in the founding of a Slavic state on the territory of

present-day Czech Republic and Slovakia. The rise of the Bulgarian Kingdom in

680 and the victory of Charlemagne in 797 put an end to the Avar empire.

(from Encyclopedia Ukrainia)

(image of the moves of the “old” Avar from http://www.hyperhistory.com/)

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Caucasian_Avars

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Eurasian_Avars

Whether present day Caucasian Avar are divided from the “old” Avar by time or

language or genes or all of it, their felt coverings unmistakably seem to breath

the memory of the steppes and pastures of central Asia (of all the rugs I know,

they resemble most closely some of the nomadic kelims from the Baliksehir and

the Antalya regions in Turkey by colour schema and general appearance - but

please, let's not discuss this here and now). They seem to be an authentic ‘weave’.

The Avar kelims on the other hand seem to recrute from several sources: colour

schema from the felts, some design pattern like those rather awkward looking

‘fish-spears’ stylised almost beyond recognition also from the felts (please

notice what lovely ranks and blossoms they still are on those felts); highly

stylised blossoms (if that is what they are) possibly derived from Daghestan

area pile rugs that utilized a floral rendering of the ark (often turned 180°)

as a field motive; shield motive from anywhere, it apparently being one of the

most widely distributed kelim motives in the eastern Caucasus and across the

southern border (possibly related to one of the main motives in those dragon

carpets). Besides aesthetic wants, those blossoms faintly resemble the ark motive

in the Synagogue carpet, be it chance or not. A religious significance in it

seems unlikely, the Avar being Sunnite Muslim.

The Lesghi rug plays in a different aesthetic league, it echoes the ark that

has been put onto or before a shield in this instance, also accommodating the

obligatory birds, all not unlike in the well known shield carpets.

Referring to the piled Avar rug you were saying: “I draw your attention to the

motif of the knotted-pile rug. Isn’t that a stepped roof or gable? The “necks”

looks suspiciously like birds too.”

It may have been a stepped roof or gable a long time ago; those ‘necks’ or ‘birds’

look as much like birds as they look in some Turkoman designs - to my shame

I have to admit, I was never able to decide whether I should think of that interpretation

as highly stylised or far-fetched.

Regards,

Horst

What means SOR-RAB in Avaric language?

Posted by Horst Nitz on 07-04-2006 07:55 AM:

Hi Filiberto

This is my long overdue reply to your last post, I apologize.

Some time ago our national prince poet and great thinker Johann Wolfgang von

Goethe (1749-1832) found the following words to caution against liberal use

of categories and abstractions in literature: “Im Ganzen haltet Euch an Worte

- dann geht Ihr durch die sichere Pforte zum Tempel der Gewissheit ein (words

lead through a safer gate to certainty than abstractions and generalizations

do).” Could he have had rug terminology in mind? Building to readily on abstractions

and categories inherits the danger of creating a reality uncoupled with the

real world.

Such caution seems all the more warranted if there is uncertainty as to background

or context of those categories. Tschirkovs credentials would probably be the

highest within a Soviet academic context. However, as the book was published

in Moscow in 1971 it doubtlessly had to get approval by the state censor, ensuring

that everything was represented according to official doctrine. This limits

the conclusions that can be drawn from this and other publications at the time.

An example: In the early 19th century the incorporation of Dagestan & Azerbaijan

into Tsarist Russia meant that the Mountain Jews became Russian subjects. In

1830 a 30-year uprising against Russia headed by Shamil broke out in the highlands

of Dagestan. The rebels founded a fundamentalist Islamic theocracy, an Imamate.

All infidels, primarily Jews, had to adopt Islam or flee from the highland villages

to areas controlled by the Russian army. Their principal havens of refuge were

Derbent in Southern Dagestan along with Krasnaya Sloboda.

In the second 1/2 of the 19th Century migration increased. Mountain Jews moved

to centres they had never inhabited before. It was then, that Baku began to

grow along with other settlements founded by the Russian authorities. Civil

war stimulated further Jewish migration from the isolated and unsafe highland

villages. This migration of the Mountain Jews continued throughout the 20th

century. Once primarily involved in agriculture, they now live almost entirely

within the cities.

This is the kind of historical and political context information necessary to

evaluate assumptions by Soviet authors. They would have known about those circumstances

but usually have chosen or had to choose to leave them undisclosed.

It is a reasonable assumption that the ark went under the gable of those Daghestan

prayer rugs at the time of Shamil as a display of individual alliance with the

Islamic national resistance, also ensuring the own skin this way. Oldest rugs

of this type date to the early 19th century – coincidence?

Is this historical context considered in Tschirkows book?

Has anybody ever wondered why 180.000 Jews living at the doorstep of one of

the great Soviet rug scholars were never mentioned, or why Eiland & Eiland

in 'Oriental Carpets' were complaining bitterly about skewed representation

of their research on Armenian rugs (‘profound prejudice’ - Chapter 8, note 15,

p 359) ?

Regards,

Horst Nitz