by Walter Davison

I want to start with an admission that I am no expert in the area of Southeast Asian weavings, but as I look at the subject, it is becoming more and more fascinating for me. I would share with you some of what I am learning. I may very well make some errors in this presentation, so if there are among you some who have expertise with this type of weaving, I ask for your patience but still hope you will correct me if you see something out of place.

Modern northern Thailand is an area with a long history of textile development by numerous ethnic groups, primarily the Tai and sub-groupings of the Tai. Where the Tai originally came from has not been definitively established, but the common belief among the Thai people today is that they first migrated to the area from southern China as early as the 1st century. The Tai have occupied what is now part of south China, Burma, Thailand, Laos, and Cambodia for hundreds of years, and in all of these areas distinct weaving patterns have been developed.

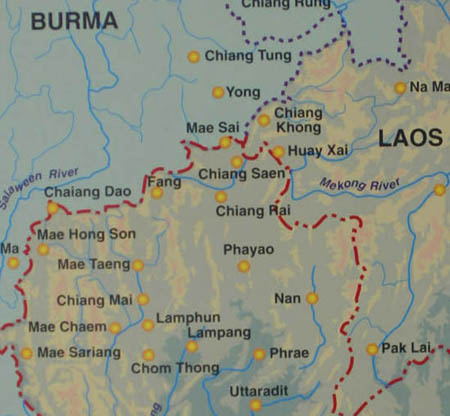

There is a particularly rich ethnic diversity in weaving cultures centered around Chiang Mai in the northern part of Thailand (see maps). Chiang Mai, now the second largest city in Thailand, was the main city of a kingdom of city states called Lan Na, founded in the mid 13th century and encompassing what is now northern Thailand and western Laos. Lan Na (or Lanna) was integrated with the kingdom of Siam in 1892.

Both the French and British had interests in this area at that time, and integration was part of the answer to those threats. Siam was renamed the Kingdom of Thailand in 1939, and since then all its citizens are referred to as Thai. It should be noted that Thailand is the only country in the region that escaped western colonization. The maps were derived from Susan Conway’s book, Silken Threads Lacquer Thrones: Lan Na Court Textiles, River Books, 2002.

The area that used to be Lan Na is historically rich in weaving cultures, with both hill tribe people and valley settlements, and is still so today. This is where the various Tai groups, Tai Khoen, Tai Lue, Tai Yai, and Tai Yuan peoples live. The Tai Lao and their various sub-groupings in eastern Laos and in northeastern Thailand have different weaving patterns and designs from these northern Tai.

The variety of the both the weaving styles and patterns in Thailand is such that it would be easy to be overcome by the complexity of the subject. Rather than attempt to describe a large area, I thought it would be more instructive to focus primarily on just one small weaving area and try to describe whatever I could about that. The focus of this presentation, then, will be on Mae Chaem weavings. While visiting Chiang Mai, we took a trip to the Mae Chaem district and into a very small town named Mae Chaem, two to three hours by mountain roads southwest, where people of Tai Yuan descent live. The women weave their pieces with the back side of the cloth facing them. A woman demonstrated the process for us.

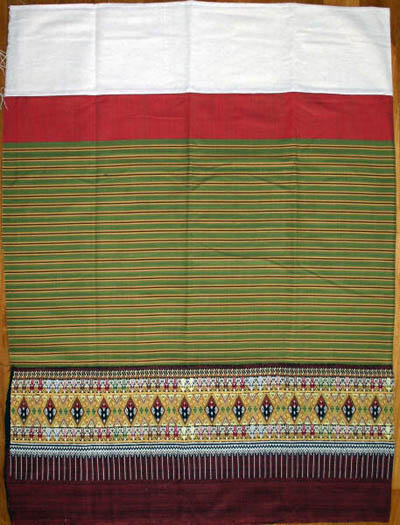

The particular aspect of weaving this area is famous for is the piece called

a “teen chok,” a decorated hem border with a discontinuous supplementary-weft

pattern which is attached to the bottom part of the central panel of a wrap

around skirt called a “phasin.”” The phasin skirts are often

made in four sections or bands; the top waist band of undyed cotton which

is attached to a second band of red or brownish cotton, a wider central panel

often made of silk (or cotton) which in the northern areas typically has horizontal

stripes, and a bottom panel or hem that reaches to the ankles. The bottom

panel of the phasins from Mae Chaem, the “teen chok” where “teen”

denotes a bottom hem usually, but not necessarily, made of any of several

dark colors, and “chok” (or “jok”) which refers to

a discontinuous supplementary weft pattern weaving, and it is this part that

is so distinctive in the Mae Chaem work as well as in other pieces from the

Lan Na area. The chok is woven in either cotton or silk and can be quite complex

and colorful. Here are close-ups of work at the loom followed by a photo of

a Mae Chaem phasin that I bought.

The last picture above is a newly made Mae Chaem all cotton phasin in traditional format. Only half of the piece is shown here. Unfolded, it is 60” wide and 40” high. It has three parts: the top undyed cotton is sewn to the central section whose top is red with the main section of green, yellow, and black stripes. The teen chok is sewn onto the bottom of the central panel.

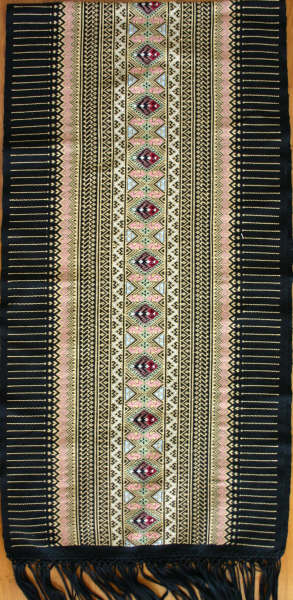

Here is a picture of a section of the Mae Chaem “teen chok” followed by close-ups of the front and back of the central medallion-like figure. This pattern is made by hand with the aid of a porcupine quill – the backside of the piece faces the weaver. (An aside: though documentation on Mae Chaem teen choks always refers to the use of porcupine quills for intricate work, one dealer I talked with in Bangkok told me that nowadays the weavers use tiny, and very sharp, bamboo fragments since porcupines are now scarce.) An almost identical Mae Chaem teen chok can be seen in Susan Conway’s text, Thai Textiles, British Museum Press, 1992, p. 136.

A closer view:

The backside in the first picture below is what the weaver sees as she does her work. The 2nd picture below is the same section of weaving as seen from the front side.

When I purchased the phasin above, I should have looked more carefully at what these two pictures show, that is, I should have done my homework better. The back side on a better quality piece would appear more like the front side than is the case in this example. I also bought another piece, a sampler of sixteen different teen chok patterns though not all the very best of quality, which does illustrate how the back as well as the front can have a more finished look. Two sets of pictures, front, then back, illustrate the kind of quality I should have been aware of when I purchased the complete phasin. Here’s the first set.

And here’s the second set.

In the second set of pictures, you may notice that it is hard to determine the front from the back. That’s what I should have been looking for when I bought the phasin.

This is a picture of an unfinished Mae Chaem teen chok.

Although the traditional Mae Chaem designs are being maintained, modern and attractive teen choks based on, but differing from, traditional patterns are also being produced. Below is a modern style Mae Chaem teen chok, all cotton. It’s folded so that only half of its longer measurement is shown. Its full dimensions are 17” by 68.” The fringe was added in case someone might want it as a scarf or long table covering. The colors are most true in the close-up picture. This teen chok, though still made completely on a hand operated loom and of good quality, does not have as much porcupine quill hand work.

Here are pictures of both the front and back of this modern style teen chok.

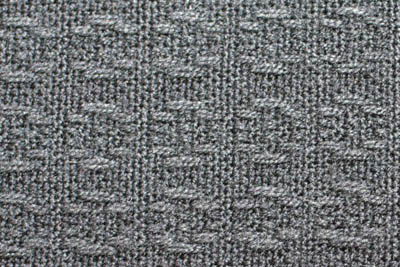

For contrast, I want to show two other phasins, one from Sukhothai with a striking black color, and a beautifully done phasin made by the Tai Khoen people who live north of Chiang Mai and in the Burmese Shan States. Sukhothai was the capital city of Siam from 1238 to 1360, and that kingdom marked the beginning of the Thai nation. It is located about 100 kilometers south of Uttaradit which is on the map above.

The Sukhothai phasin’s top panel is a very dark reddish brown while the central panel is an intricately patterned black cotton piece. The Sukhothai pattern in the central piece is made with rayon which keeps it from wrinkling. It’s 38” high, and its unfolded width is 64”. It does not have extra hand work as the Mae Chaem pieces do.

Below is a closer view of the teen chok on this piece.

The pattern in the central piece is hard to see since it is all black, but you can see it in bright light. In this close-up the black comes out as grey with the pattern visible.

The other impressive weaving is an all cotton Tai Khoen phasin, and

it’s about 50 years old according to a well-informed local collector.

The Tai Khoen people were settled in Chiang Tung in what is now Burma and

also in Chiang Saen, north of Chiang Mai near the city of Chiang Rai in Thailand.

Both these cities are on the above map. We found this piece for sale in a

night market fair in Chiang Mai. Again, it has three bands of cloth as in

the other phasins. A very similar Tai Khoen phasin with a satin hem is shown

in Susan Conway’s text, Silken Threads … on page 167.

She labels it as coming from Chiang Tung.

Here is a close-up of the central panel.

Lest some may think that textiles of this sort, though perhaps interesting and colorful items, are not actually worn today by modern, urban Thais, I can tell you that that idea would be mistaken. On an early evening excursion into the market place in Chiang Mai, we encountered this charming lady wearing a beautiful phasin covered in teen chok like weaving. She told us that she had special ordered it and that it took six months to complete.

I’ve been coming to Thailand for many years, and I had never paid any attention to these things, I am now sorry to say. It was partly because of Turkotek that my horizon has expanded a bit. It just goes to show you: older dogs really can learn new things. I hope you have enjoyed this short glance at this amazingly rich source of weaving.