Part 2:

In Oriental Rugs and Textiles

by R. John Howe

A second use of complementary color seems to me to be less successful.

The

purple-gold-red combination doesn’t work for me in this detail of a

large kilim attributed to southwest Anatolia.

So far we’ve dealt with:

Color harmony

Analogous colors

Complementary colors

It should be clear now

that there is a relationship between analogous vs. complementary colors

and what we call “contrast.”

Color “contrast” is a visual effect that is

the result of where colors are on the color wheel.

Analogous colors have lower contrast with one another.

Complementary colors have higher contrast with one another.

Compare the various color combinations above with regard to contrast and notice how analogous colors and complementary colors operate with regard to it when placed side by side.

Proportion and Dominance

The color with the largest proportional area is the “dominant” color (often the ground color).

Smaller areas are “subdominant” colors.

“Accent” colors (which we have mentioned more than once above) are those with a small relative area, but offer a contrast because of a variation in hue, intensity, or saturation.

Weavers often use a dominant color to hold the overall visual effect of a weaving together. The Kazak piece below, despite often having deeply saturated colors used in sharply contrasting ways, also uses a dominant color to maintain the visual whole.

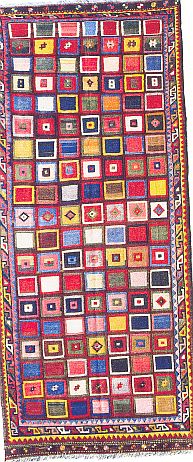

Here is a colorful piece that seems to me more fragmentary-looking because no particular color seems dominant.

Although dominant colors often work to hold a piece together visually, subordinate colors can have more effect than one might think. It sometimes takes only a little variation in a subordinate color to product fairly dramatic effects in a weaving.

The rug below is a small Ersari. It uses a strong, but subordinate, yellow to dramatic effect. But notice that while the rug is still held visually together by the dominant reds of its ground color, one of the first things noticed is its overall chaotic appearance.

In addition, the use of the dominant red in both the field and as the ground color for the main border (which does contain some substantial devices of a different scale and color from those used in the field) prevents the main border from performing its framing function in a satisfactory way. It is interesting how great the effects of these two color usages are in this rug.

Oddly, I do not personally find this piece unattractive. Its very chaos is what has tempted me to have it copied so that I could look at its design often.

We have mentioned Accent colors previously – usually high contrast colors. They

have the effect of making our eyes jump around on a work of art rather

than of responding to the whole.

The accent white in this Karachopf Kazak works to move our eye, not just to the center of this piece, but to its four corners.

Accent effects – An accent effect can also be produced by changing either the actual “texture” of a weaving or its apparent texture. Mixed technique pieces often use both changes in color and texture to produce accent effects.

Bakhtiari bags such as the one above are famous for using mixed techniques to produce accent effects.

Color theory suggests that the deep blue field should be experienced as receding in perspective. The minor red borders should occupy a middling distance and the white ground border should appear closest to us. Do these colors produce these effects for you?

An interesting elaboration of this phenomenon is that since the medallion devices on the white ground border are darker than it is, they should in theory be seen to “punch holes” in it and to move to more distant levels. What do you think?

Here is a Caucasian piece with a white ground and darker borders. Does the white ground of the field seem closer?

This piece also lets us compare how the same colors look against lighter and darker grounds.

Here is a more complex instance of colors effect on dimensionality. The piece below is a Senneh kilim with a niche design.

Color theory posits that we should experience the dark ground of the field under the mirhab as furthest from us and the white ground of the field above the niche form as closest to us, with the red of the borders in a middling distance. Does this happen for you?

Looking closer, such effects should even be visible in the color effects used for the boteh devices.

First, the botehs in the dark part of the field should appear to float on it, while the devices in the white ground areas should be experienced as being at levels beneath that ground. And looking at the botehs in the area under the niche form, the white edges should look closest, while the green and red areas at a middling distance and the dark ground (within the botehs) furthest. Looking at the edge of the niche form in the close-up, one should experience the green-red border as moving above the dark field but beneath the adjoining white field with the dark outlining on this border serving as a kind of etching of it. Do all of these theoretical effects of color use in this piece produce the predicted visual experiences as you look at it?

One more instance of the way that weavers attempt to suggest dimensionality with color. The Moguls are famous for having used close colors next to one another without intervening outlining, what is called the “ton-sur-ton” usage. Here is a glorious Mogul rug.

Now I’ve gone on a bit here about color theory and color as we experience it in rugs and it’s clear that this is a subject that is nearly inexhaustible, although some readers may long since have become exhausted by my rather discursive treatment of it here.

So what should we do in this salon?

Well, we can offer examples of rugs and weavings that illustrate various aspects and uses of color.

We can debate whether color theory is, in fact, always borne out in our experience.

We can offer examples of color usage that seem to us to be less successful.

We can also talk about a number of aspects of the use of color that I have not really dealt with above. Here are a few possibilities (some of which Tom Xenakis dealt with in his talk):

Use of color to affect graphics – how color affects how we experience the graphic elements in a piece of art.

We could explore our views of “saturation” or “intensity” of color. We tend to respond positively to pure, intense color.

“Luminosity” is another term for characterizing “intensity” of color. In weavings this can be enhanced as “patina” emerges (a sheen that can develop as colored wool is polished with age and use). We could ask ourselves why patina is seen to be attractive on an oriental rug, but not on a pair of blue serge dress slacks. It’s just a “shiny-ness” after all.

We could also ask whether we are not sometimes inconsistent in admiring deeply saturated colors and then moving quickly to also compliment softer ones that have been “nicely modulated” by age.

There are symbolic uses of color – Color means different things in different cultures. Some of these symbolic meanings of color are interesting.

Colors have temperatures. Yellow, red are warm. Green, blue are cool. Are there things to notice about this dimension?

Collectors often refer to color palette, usually in the context of making attributions. Rugs from particular areas are often seen to have colors that comprise a typical palette. It is often argued that rugs not having this palette of colors are not likely to have been woven there. Do we know what we’re talking about when we make such assertions?

Tom pointed out that there is an “economics” of color. That is, some colors are more expensive to make. This is especially true of colors that require “double-dyeing.” “Double-dyed” colors include:

Green

Aubergine or purple

Orange (at least some)

These colors have traditionally been both difficult and expensive to make soundly. That likely accounts, in part, for some of their appeal to scholars and collectors.

Cochineal reds, while not double-dyed, have also been expensive to produce, as are the colors produced by the direct use of gold and silver in weavings.

And, of course, there’s lots of discussion in our world of colors and dyes:

Tom said that the “natural” dyes vs “synthetic dyes debate with regard to weavings is analogous to the “natural” paints vs acrylics in painting. Acrylics have some desirable features (e.g. fast drying) but we don’t know yet what pieces painted with acrylics will look like several hundred years hence. We do know that some natural paints have retained bright, strong colors for over 2,000 years.

We know that some early synthetic dyes faded and changed dramatically in relatively short time. We do not yet know what “chrome” dyes or even contemporary “natural” dyes with look like several hundred years from now, but we do know that the natural dyes in some 15th and 16th century Turkish and Persian rugs can exhibit colors with wonderful purity and saturation today.

Early synthetic dyes were often garish, lacked harmony and as they changed lost balance and affected the unity of the entire weaving.

The quality of wool seems important to intensity of color and the color of the structural materials may sometimes have some effects on the visible aspects of a weaving.

At the most obvious level, the warps of Senneh pieces with multicolor silk ones are used in part to enhance the visual experience with the rug. These warps are meant to be seen. It is also possible that the choice of foundation colors may sometimes be made by weavers either to avoid or to achieve certain other effects on the surface of the weaving itself. (It may be useful for a rug with a lot of white ground not to have warps or wefts with more definite colors.) Eiland reports that in some places the color of the wefts are varied to make it less likely as a rug wears that the structure will “show through.”

And there is also the chemical alteration of color after dyeing and weaving. Weavings can be both “bleached” and “painted” to produce particular color effects. (e.g., painted Sarouks). In general, bleached and painted rugs are not seen by collectors to have attractive colors.

Nowadays, since rug and textile repair has become more economic, color can also be altered during repair and restoration. This can lead to debates about the morality of some uses of color in such repair work.

So you can see the possibilities here are very broad indeed. This could be a salon that is accessible to most everyone, and that could be useful, as well as, enjoyable.

Let the “colorful” discussion begin. (My God! I just thought: I’m going to have to summarize this thing.

)

)Regards,

R. John Howe

Image Sources

(Number sequence has gaps; no rugs used are missing from this listing)

(You can discover the number of a given image in this essay by

putting you cursor on the image, left click, then right click and choose properties from the drop-down menu.)

Color 1a Detail of image in Color 1 above.

Color 2 Jon Thompson, “Oriental Carpets,” 1988, p. 7.

Color 3 Alastair Hull and Jose Luczyc-Wyhowska, “Kilim,” 1991, p. 193, Plate 148.

Color 4 Parviz Tanavoli, “Lion Rugs from Fars,” 1974, p. 49, Plate 23.

Color 5 Hallvard Kare Kuloy, “Tibetan Rugs,” 1982, p. 132, Plate 99.

Color 6 Ian Bennett and Aziz Bassoul, “Rugs of the Caucasus, 2003, Plate 79.

Color 7 Ulrich Schurmann, “Caucasian Rugs,” 1974, p. 137, Plate 40.

Color 8 Ulrich Schurmann, “Caucasian Rugs,” 1974, p. 75, Plate 10.

Color 9 Ulrich Schurmann, “Caucasian Rugs,” 1974, p. 241, Plate 87.

Color 10 John T. Wertime, “Sumak Bags of Northwest Persia, p. 151, Plate 87.

Color 11 Louise Mackie and Jon Thompson, “Turkmen,” 1980, p. 70, Plate 6.

Color 12 Elena Tzareva, “Rugs and Carpets from Central Asia,” 1984, p. 135, Plate 89.

Color 13 Parviz Tanavoli, “Persian Flatweaves,” 2002, p. 97, Plate 46.

Color 13a Detail of piece in Color 13 image above.

Color 14 Raoul Tschebull, “Kazak,” 1971, p. 41, Plate 11.

Color 15 Raoul Tschebull, “Kazak,” 1971, p. 85, Plate 33.

Color 16 Raoul Tschebull, “Kazak,” 1971, p. 99, Plate 40.

Color 17 Photo of a Flatwoven mafrash that Tom Xenakis showed in his TM rug morning.

Color 18 Photo of a Bakhtiari soufre that Tom Xenakis showed in his TM rug morning.

Color 18a Detail of image 18 above.

Color 18b Detail of image 18 above.

Color 22 Yanni Petsopoulos, “Kilims,” 1991, Plate 91.

Color 22a Detail of image 22 above.

Color 24 Yanni Petsopoulos, “Kilims,” 1991, Detail of Plate 35.

Color 26 Ralph Kaffel, “Caucasian Prayer Rugs,” 1998, page 113, Plate 60.

Color 26a Detail of rug in image Color 26 above.

Color 27 Parviz Tanavoli, “Persian Flatweaves,” 2002, p. 132, Plate 106.

Color 27a Detail of image 27 above.

Color 28 Parviz Tanavoli, “Persian Flatweaves,” 2002, p. 171, Plate 127.

Color 29 James Opie, “Tribal Rugs,” 1992, page 139, Plate 8.9.

Color 30 Parviz Tanavoli, “Persian Flatweaves,” 2002, p. 110, Plate 60.

Color 31 Ulrich Schurmann, “Caucasian Rugs,” 1974, p. 167, Plate 53.

Color 32 Daniel Walker, “Flowers Underfoot, 1997, p. 60, Fig. 54.

Color 32a Detail of image 32 above.

Color 33 Photo of a Kurdish rug with deep corrosion in blue areas that Tom Xenakis showed

during his TM rug morning.