Posted by David R.E. Hunt on 12-20-2005 11:40 PM:

How Do I Love Thee, Let Me Count The Colors...

Greetings Everyone

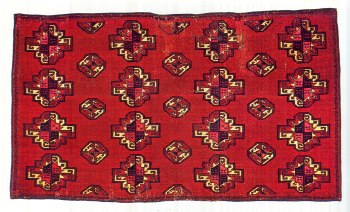

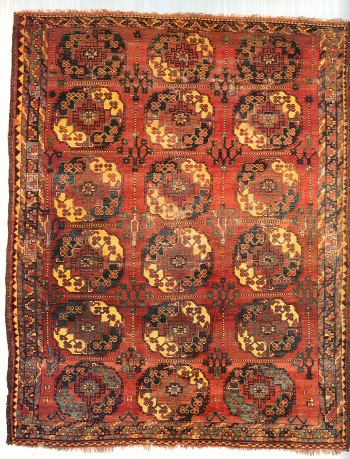

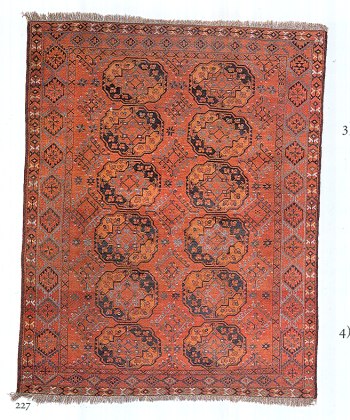

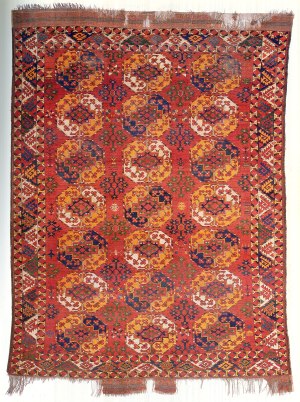

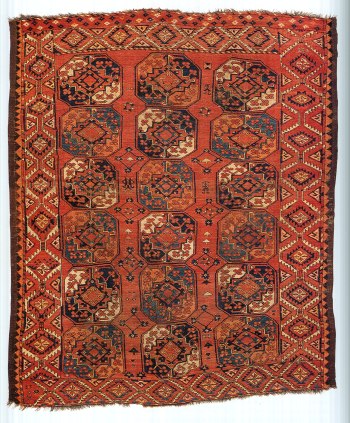

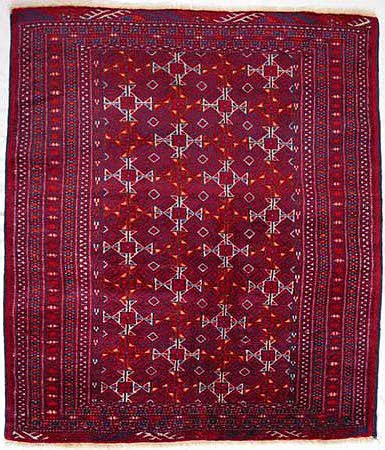

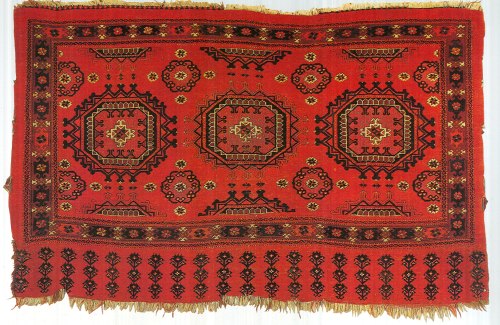

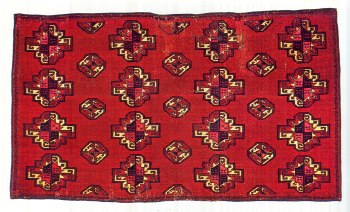

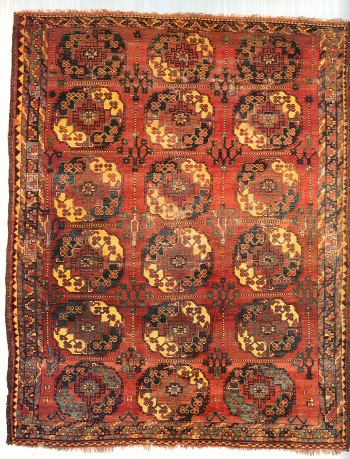

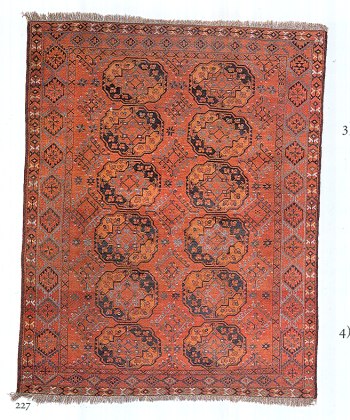

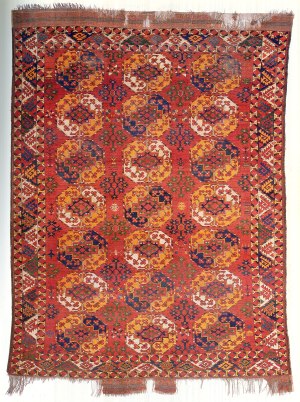

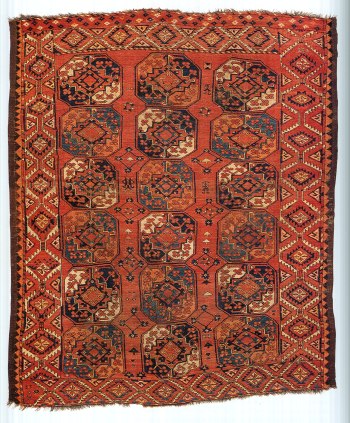

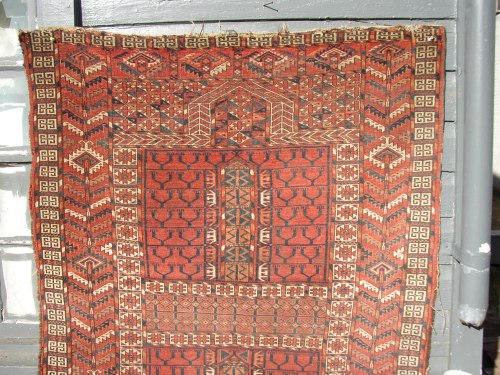

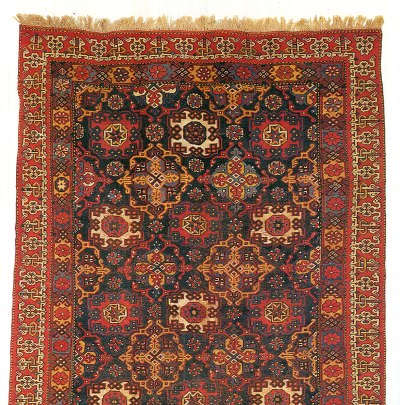

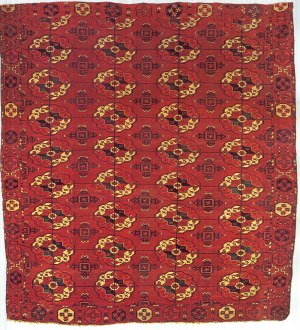

I have recently purchased this antique Ersari juval.

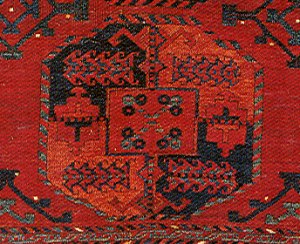

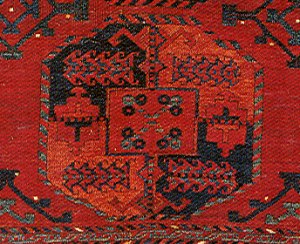

At 34"x50" it is large, and sports a 3x4 layout of huge archtypal major guls

(the first depicted below is 9" wide and 7" tall) and this triangle variant

of a chemche. Real simple kochak border with two barber pole guards. Doesn't

come much simpler than this. The detail of the drawing is superb, I do believe,

and with three blues, an interesting green, red, yellow, brown, ivory and apricot,

quite a range of colors. Thick, dark coarse warps, two shots of weft, 8h. x12

v. open right, flat on the back with no ridges, almost like a Tekke, and a low

pile which is glossy and colors of depth which really respond to light. An interesting

object all around, even smells good.

I suspect this is on the further end of the age spectrum for an Ersari, and

the colors are great (I think?). The deep red, couple shades of blue, the green

and yellow, all textbook older Ersari characteristics, if memory serves. And

especially this apricot color seen in the guls.There is a strong green component

in this light blue, it's almost a bluegreen.You really have to see this chuval

in person to appreciate it, the scale of the design,the depth of the colors.

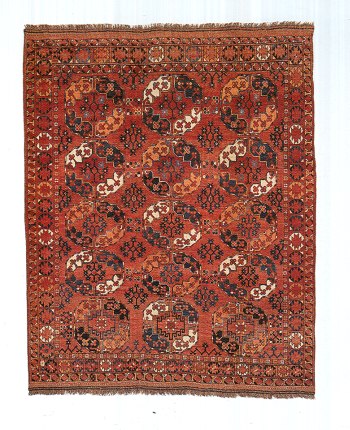

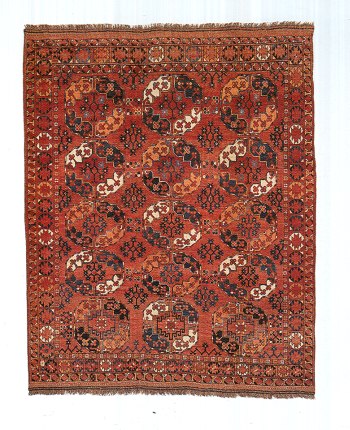

The difference you see in the two full images is entirely a consequence of the

amount of light . In normal indoor lighting the field is a deep mahogany color,

but bring it into bright light and it becomes this supersaturated red.

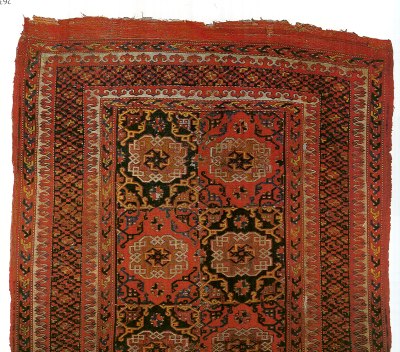

This bagface demonstrates some interesting qualities color wise, and I invite

everyone to utilize some of these precepts of color harmony to better understand

color use in this weaving.

Dave

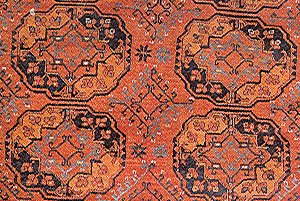

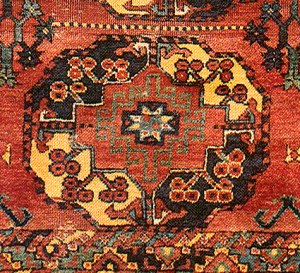

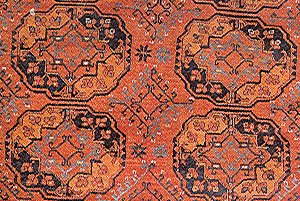

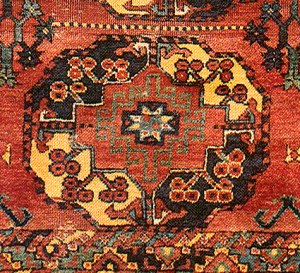

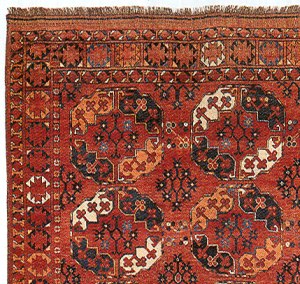

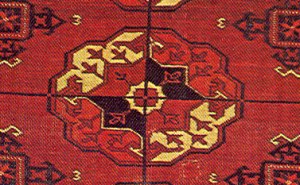

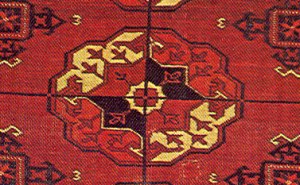

Here is the 9" x 7" archtypal gul. The guls vary much in size and proportion

on this bagface.

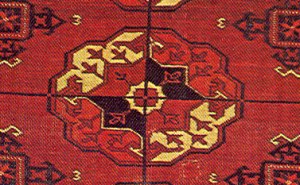

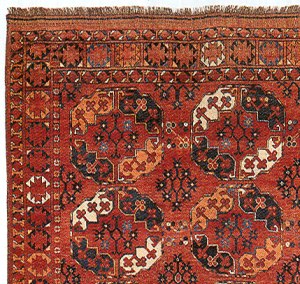

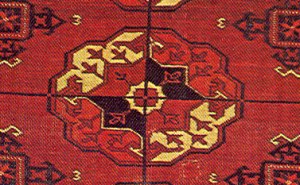

I especially like the detailed use of color in this chemche.

This wonky drawing is endearing.

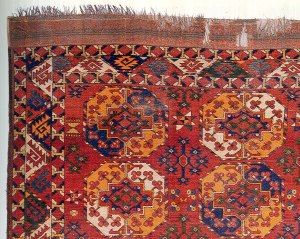

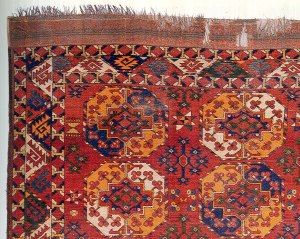

Simple border sequence and this green, both at once.

Interesting Elem in this further image.

Posted by R. John Howe on 12-23-2005 05:59 AM:

Hi David -

No one is acknowledging your piece, so let me do so.

As I said on the side, I think this is a good find, the sort of piece that I

often buy myself. Older, but with some condition problems.

You mention the large size and it is surprising how large Ersari chuvals sometimes

are.

It appears to have the more "Caucasian-like" colors that both Ersaris and Yomuts

can exhibit. The "robbin egg blue" is especially prominent and attractive.

The drawing seems traditional to me (I personally like to see "hooks" rather

than "flags" among the devices used in internal drawing of the major guls, although

Pinner and Elena said to me once that "hooks" are not an age indicator. I had

though they might be, since hooks are more complex and seem a prime candidate

for simplification, and flag usages seem to be one of the latter.).

I also think the large devices in the elem are attractive and can't remember

seeing them before (there are some Yomut chuval skirts that have four rather

massive devices like this).

I think this piece a worthy addition to your collection.

Regards,

R. John Howe

Posted by David R.E. Hunt on 12-24-2005 01:47 PM:

Hi John

Thanks for the kind words. As I assume is rather obvious, I am fond of this

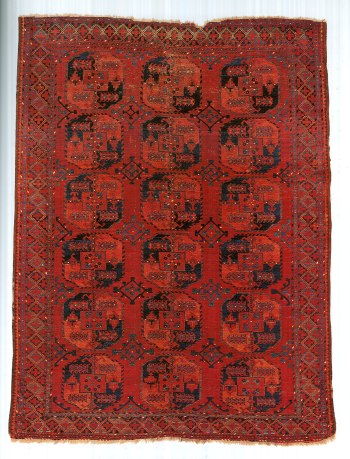

bagface. Makes a nice counterpoint to my modern Ersari

chuval .

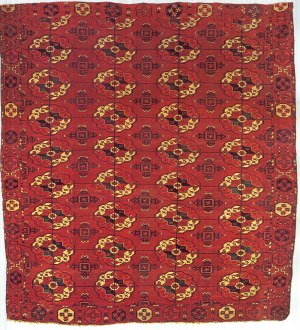

As I had noted above, this antique bagface seems to have most of the distinguishing

characteristics of early Ersari weaving. Another characteristic, as I failed

to note above, is the prominence of white in the palette.

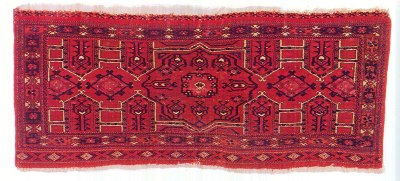

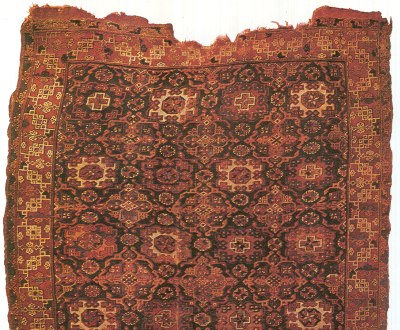

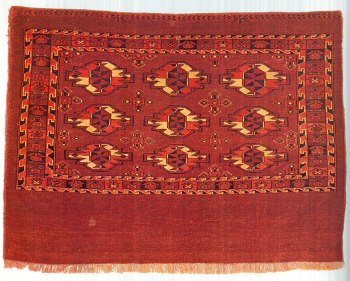

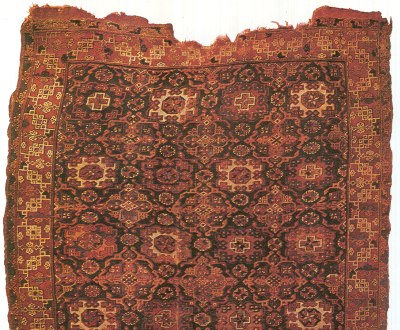

It strikes as a different approach to design than the following,

from your Salon regarding Dennis Dodd's

"Rug Morning" here on Turkotek.

This particular incarnation seems more at Salor than Ersari, compared to their

traditional gul pieces (and especially mine above ).

Any possibility that what we see going on here could be an early attempt to

trade upon the elan of Salor weaving? Barring (or inclusive) of this, representative

of an urban design pool? Some suggest a dichotomy of the Ersari design pool,

consisting of a more western, gul based repetoir and an Eastern, more urban

and Asiatic component.

Follow this link to a previous discussion of design motives in Middle Amu

Darya weaving here on Turkotek.

Your reference to caucasian weaving is interesting, especially in light of what

Eiland has to say concerning the seeming ethnic composition of the Turkmen in

"A complete Guide;

"There are Yomut and Goklan of northeastern Iran who strongly resemble the Kazakhs

of Central Asia. The Salors have a more "Asian" look, giving them an appearence

that more resembles the Uzbekis. The Tekke of Ashkhabad and Merv, however,look

far more Iranian than central Asian."

This elem, with it's four large kochak/lattice devices is for me a high point

in this weaving. In this respect it is unusual, but more at interesting than

odd.

This bagface is difficult (at least for me  ) to photograph, making it challenging to convey the qualities of the colors.

The richness and variability, in accordance to the amount of light, is especially

interesting. Mahogany, Terra cotta, and Tomato are all accurate description

of the ground color under various light conditions. I believe this chuval does

achieve what the color theorists characterize as color harmony, as it can be

argued to demonstrate:

) to photograph, making it challenging to convey the qualities of the colors.

The richness and variability, in accordance to the amount of light, is especially

interesting. Mahogany, Terra cotta, and Tomato are all accurate description

of the ground color under various light conditions. I believe this chuval does

achieve what the color theorists characterize as color harmony, as it can be

argued to demonstrate:

A dynamic balance

Visual interest

A sense of order

The red ground counterpoints the sense of motion conveyed by the real physical

movment, as we fix upon the different colors and elements of the composition,taking

them in. The contrasts in the colors, some of them striking, as in the ivory

and this almost electric blue, is counterbalance by the close filial relationship

between the colors. For all it's apparent complexity, the palette consists of

three representatives of primary blue, one each of the red and yellow primary,

and two tertiaries. Hence the palette relies heavily upon analogous and complimentary

colors. Note the color use in the following chemche gul,

and the positions of the respective colors on the color wheel.

And as for a sense of order, the Turkmen gul format, with it's repetative use

of color in it's borders and guls, is a sense of order of the highest, well,

order.

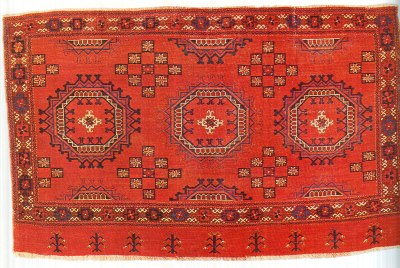

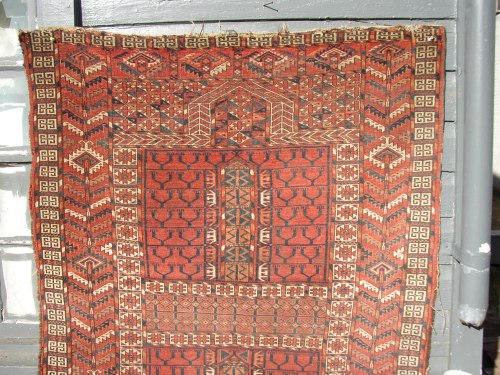

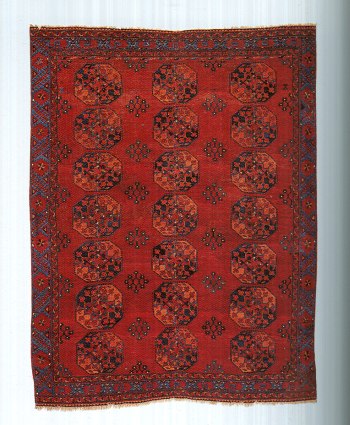

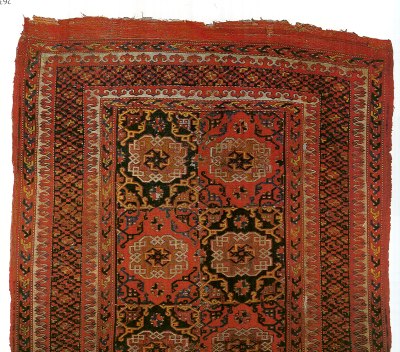

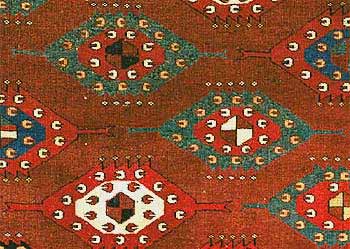

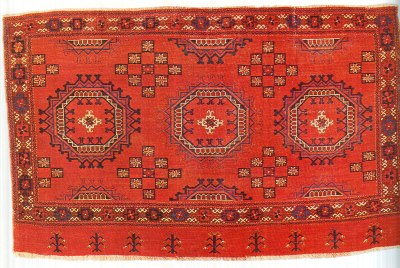

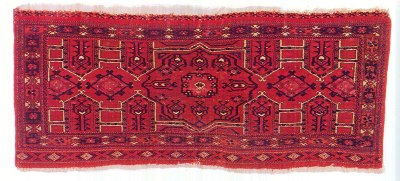

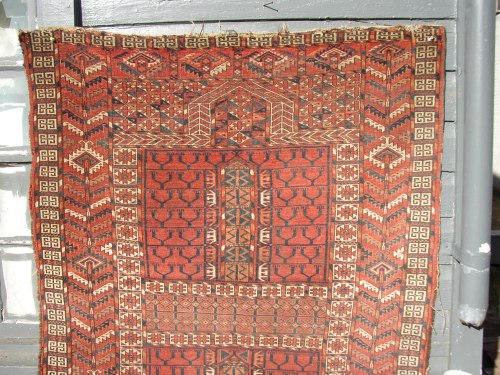

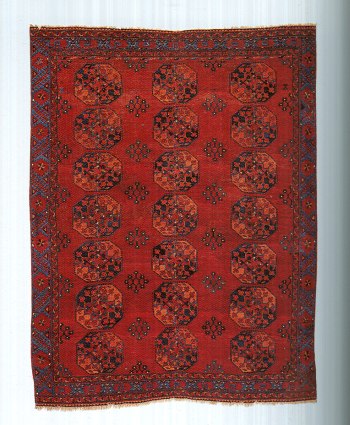

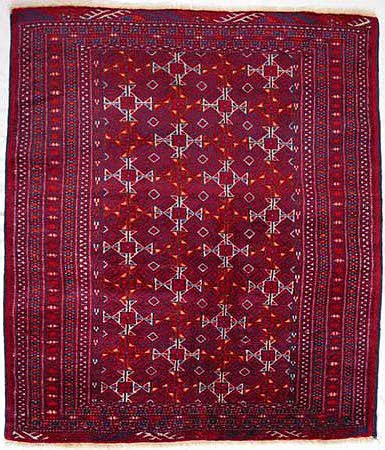

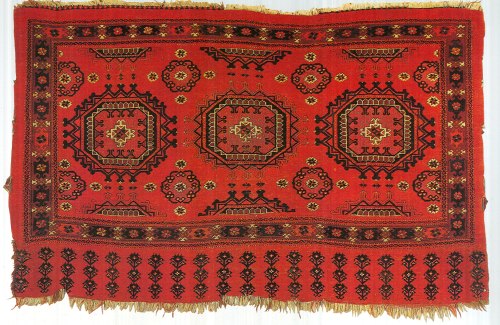

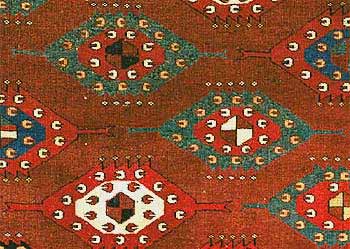

I picked up this Kirghiz bagface (30" x 41") with the guli gul and kochack border,

dice border and what could be a precursor this stepped "ribbon" border, so often

seen in Ersari and Saryk ( I think?) work. Seems some authors are of the opinion

that Kirghiz weaving is a recent occurence, relative to that of the Turkmen.

The Eilands, in their latest edition of The Complete Guide, view them as being

a potential, elder repository of Turkmen carpet designs.

Could these simularities be further manifestations of the Eastern vs Western

dichotomy mentioned above?

Happy Holidays and a Great New Year,

Dave

Posted by Ashok_Patel on 12-30-2005 07:58 AM:

Mr. Dave,

When you write on this discission, "This particular incarnation seems more at

Salor than Ersari, compared to their traditional gul pieces (and especially

mine above )" what do you mean. Where are your comparative salors and what about

these, especially your bedding sack face makes you say salor. This I do not

see. I will be gone for a few days I am taking my wife home to Morocco since

her brother was in an accident. I will try to read the internet from there but

I have no laptop. Maybe I find cyber cafe. Maybe you can give me book name to

see Salor that look like Ersari when I come back. When I think salor I think

of bloomed mader red not browny madder red.

Posted by David R.E. Hunt on 12-31-2005 01:54 PM:

Hi Ashok

It's a reference to the border sequence and it's composition, among others.

I had specifically stated "compared to their traditional gul pieces" as a reference

to design.

Dave

Posted by R. John Howe on 01-04-2006 06:16 AM:

Hi David -

I have to admit I'm not seeing the Salor similarity you mention either. In fact,

the main border on your piece is one area in which it seems to me there are

signs of conventionalization. This border appears in Tekke pieces, in the Saryk

you show here and in Ersaris, as well as in the non-Turkmen Central Asian piece

you also provide. Versions of it appear in some Salor pieces as well (I am looking

at Plates 2 and 5 in Jourdan) but Salor main borders are more often diamond

shaped devices.

Ersari weavings may often not need the support of comparison with the august

Salors. Marla Mallett has said somewhere that as she has examined a great many

Turkmen pieces in recent years, she has found that the oldest instance of a

number devices seems to occur in Ersari pieces. She speculates that Ersari design

may in some instances have served as a kind of source for other Turkmen weavers.

Regards,

R. John Howe

Posted by Ashok_Patel on 01-04-2006 11:44 AM:

Mr. R.,

Very interesting. Did not the Ersari Saltuq rule the Salor but the Salor never

ruled the Saltuq. All Turkmen were ruled by the Ersari except maybe the Yomud.

Who is this Mallet who knows so much?

Posted by Steve Price on 01-04-2006 12:29 PM:

Hi Ashok

Marla Mallett is the author of "Woven Structures", an excellent book about,

well, about woven structures. She's also got a nice website, with loads of information

on it, at http://www.marlamallett.com/

Regards

Steve Price

Posted by David R.E. Hunt on 01-04-2006 09:37 PM:

East vs West, Continued...

Hi John

The similarites I mention are only superficial, just the internal drawing or

"instrumentation" of the archtypal guls and the kochak variant of the border,

as in Plate 6 from T.M's "Turkmen" below.

Plate 6, mid 19th cent. Salor Tribe

Don't get me wrong, I dont really understand the process by which these come

to look so much alike. But Thompson has some ideas, as from "Turkmen", pg. 67,

below.

"The oldest weavings of each tribe frequently provide suprisingly clear evidence

of an early relationship between them in terms of their designs. The further

back we look the more comon ground

we find, which points to a common ancestry for many Turkmen designs. As the

awareness of Turkmen weavings has grown and previously unknown old rugs becomw

available for study, similarities between the tribes emerge that are not evident

in later examples.This suggests that some designs have originated

from a common ancestor at some time in the distant past and that these designs

have undergone successive modifications in the hands of different tribes. The

various forms of the quartered-lobed-gul suggests an early relationship between

the Salor,Saryk,Tekke,Ersari, and possibly Arabatchi.

The exact nature of the relationship is not clear. It could be one of geographical

proximity, military alliance, cultural affinity or, as the legendary history

of the tribes would suggest, an origional tribal unity, later subdivided".

Well and good, but for a moment let's go back to plate 6 above, of which Thompson

states

"The design of this bag is interesting for the comparison it provides with literally

hundereds of bags with nine guls made by various tribes, particularly the Yomut,

and with the bag in the following plate which has the same design but in a different

arrangement. The term "archtypal gul" has been coined

for this design so as to avoid a simplistic mistake of calling it by a tribal

name. Every Turkmen tribe uses a form of this design somewhere in it's weaving.

There are so many variations that it is impossible to say what form is ancestral

to annother They must all be derived from a common prototype which has undergone

various modifications over a long period of time in many different hands".

Plate 7, late 18th cent. Salor Tribe

So here we have two formats of gul layout ,the 3x3 and a 4x4.

Let's assume we are moving west and look at a pair of Yomud chuvals, also from

"Turkmen"and as discribed by Thompson.

"Two main streams of design can be detected. The first consists of ancient designs

shared by other Turkmen tribes. This stream is represented by carpets with the

archtypal gul, the dyrnak gul, and the octagonal gul with four pair of animals

the Tauk Noska design. The second stream consists of designs incorporated from

outside sources and changed gradually in conformity with the prevailing Turkmen

style".

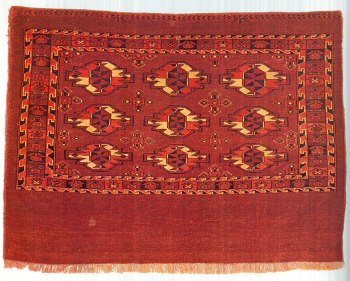

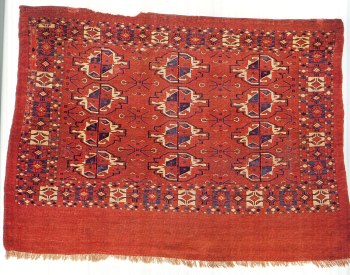

"The bag in plate 70 displays an arrangement of three rows of three archtypical

guls. It has no back, but unlike many old bags, retains it's origional width,

including the areas of solid color at both sides beyond the main border. This

empty space is important to the visual effect of the design as a whole".

PLate 70, Early 19th cent. Yomud Tribe

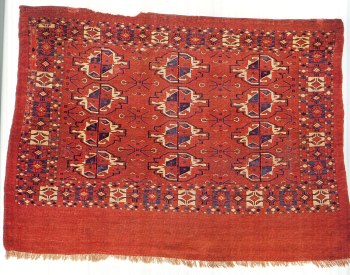

"Another variation of the archtypal gul is seen in a Yomit bag where three rows

of four guls occupy the field which is proportionately larger than the previous

example. Another version of the Chemche gul is used for the secondary

ornament. The main border and guard striopes are sometimes found in Tekke weaving".

Plate 71, Early 19th cent. Yomud Tribe

Now compare Plate 71, 70 to the Ersari in Question.

I'll come back and try to make sense of this soon.

Dave

Posted by David R.E. Hunt on 01-07-2006 08:30 PM:

East vs West, Continued...

Hi John

Let's step back from the three archtypal guls and their internal drawing for

a while (will come back to these later), and broaden the scope of the discussion.

Let's start with the Kirghiz bagface mentioned above.

This is really an interesting artifact (and apparently rare, as suggested by

Eiland in "Complete Guide"), with it's coarse weave and expansive scale of design,

the size of the guls on the bagface approximating that on gulli gul main carpets

of the Ersari. Of special note, this diamond shaped "shield" within the gulli-guls

is about the size of a Tekke main carpet gul, and seems to beckon innovation

of design. I suspect it has yielded much.

You could sew four of these Kirghiz bagfaces together and almost have a main

carpet. At 30" x 41 it's a few inches shy of the 32 1/4" x 52 1/2" demonstrated

by the turret gul Salor chuval in "Turkmen's" Plate 8 (below).

Notice the kochak border, and especially the turrets, common to both the Salor

and the Kirghiz; in the Kirghiz the turrets are suggested as the minor gul,

and it's placement contiguous with the gulli-guls.

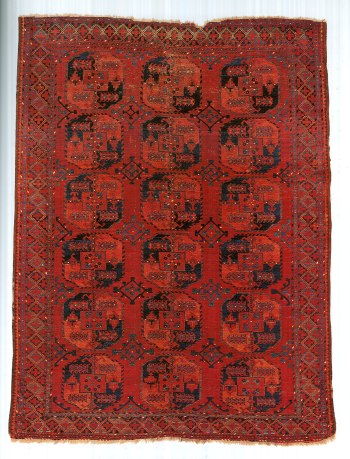

The "Ersari" main carpet from T.M."s "Turkmen", Plate 85, is accompanied by

the following caption

"The carpet in Plate 85 has large, closely spaced guls, an arrangement which

conforms to an archaic tradition preserved most noticeably in Ersari weavings.

The grid lines joining the secondary ornaments is unusual and may be the vestige

of an earlier layout. The huge guls are uneven in shape and size, giving the

carpet an early primative look. The colors, wide coarse side finishes, light

colored wefts, and crude workmanship provoke the question of exact Tribal origin.

At first glance it looks Ersari, it certainly has an Ersari design, but the

overall style is close

to a group of colorful, rough-and-ready weavings often considered products of

non-Turkmen weavers".

Notice the memling guls at the center of the "shield" device in the gulli-guls.

And compare it to the drawing of the shield region of the archtypal gul from

Thompson, Salor plate 6.

We see this same element here, to the left and right of the central medallion

in this Salor piece,

from "Turkmen" plate 9.

It is not by coincidence that this central medallion is of an octalinear configuration,

as in the minor guls of the following Ersari main carpet, plate 58 from "Black

Desert and Red".

Here the main guls are of a more rectalinear geometry, and the minor gul of

the octalinear.

Thus we have two basic variations upon geometric design progression, rectalinear

and octalinear, and representing the formentioned west/east dichotomy.

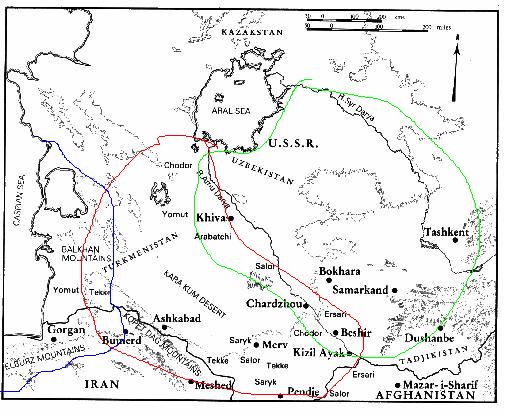

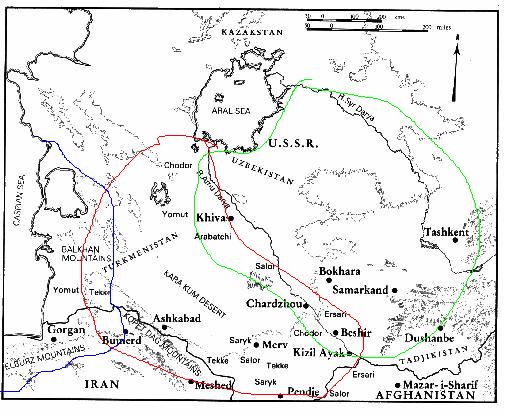

Iv'e indicated below just a rough approximation of the forces which have molded

Turkmen design repetoir, the blue line those of the Caspian region and as manifested

in the early palmette style drawing of the Ballard Yomud in the Met. To the

east, in green we have Uzbek and other central asian denizens which make this

area home and who have lived in close proximity to each other for centuries.

And in the center the Turkmen where they have resided for some time as well.

In a detail from an Ersari main carpet in Eiland's "Complete Guide", we see

this eastern, octalinear motif. Notice that the interior "shield" of these Ersari

gulli-guls approximate delineation of the archtypal gul.

Thus is the geometric relationship between the gulli-gul of the Ersari, it's

compatriots the Turkmen main carpet guls such as the Tekke, and the archtypal

gul ,which share this octalinear geometry. Of the interior drawing of the above

mentioned Yomud archtypal guls from plates 70 and 71, we see a more rectalinear

orientation.

Dave

Posted by David R.E. Hunt on 01-14-2006 10:50 AM:

East vs West, Part III

Hi John

You had stated above that

"Marla Mallett has said somewhere that as she has examined a great many Turkmen

pieces in recent years, she has found that the oldest instance of a number devices

seems to occur in Ersari pieces. She speculates that Ersari design may in some

instances have served as a kind of source for other Turkmen weavers"

and I think this fits well into the discussion of this eastern vs. western,

octalinear vs. rectalinear dicotomy. Find below a Tekke engsi which demonstrates

this more western rectalinear drawing. (Follow this link to a discussion of

the similarity this engsi design bears to traditional Persian flat weaves or

zilus )

and compare it to the internal drawing of these two guls

I would suggest of these two that the internal drawing of this second Yomud

gul from Thompson plate 70 better represents the western style, with it's simple

"banner" as opposed to the more octalinear "bracket". Yet the "twelve triangle"

design is the same in both.

Maybe this map, from "Between Black Desert and Red" can aid us in understanding

what was going on with these carpet designs.

Notice how all of the population centers ring the edge of the Kara Kum Desert,

and imagine the forces exerted if a fundamental shift in the flow of trade,

to and from the west toward the Caspian, or the reverse, toward Bukhara and

Samarkand, took place.

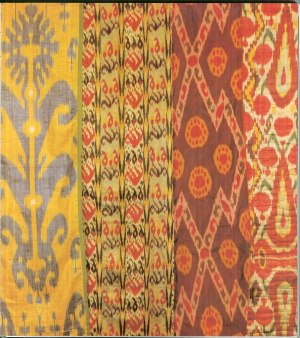

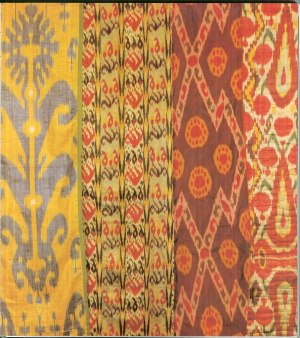

Interesting that Ikat patterns are found abundantly in both Yomud and Ersari

weaving, yet for some reason seem to prevail later in the designs of the Ersari,

Ikat designs being more prevalent in the Yomud during an earlier period(?).

If we are correct in assuming that the Ikat source lies in the east, this would

suggest the yomud were familiar with Ikat and that they traded with the eastern

cities of Turkestan. Perhaps these tendencies, rectalinear vs octalinear, are

more a consequence of geographic isolation due to shifts in trade routes, population

decline, supply/demand, spread of arid regions, ect..

Dave

Posted by James Blanchard on 01-15-2006 07:43 AM:

Hi David,

Interesting thoughts, though I am not sure how one could substantiate theories

of design "migration" definitively. Still, I think you have highlighted some

important differences within broad design categories.

I don't know very much about Yomud designs during various epochs. Here is a

Yomud rug listed as c. 1900 shown on Barry O'Connell's "spongobongo" website.

Is this an example of Yomud ikat design? Does this represent early or late Yomud

weaving?

James.

Posted by David R.E. Hunt on 01-15-2006 11:36 AM:

hi James

You had stated that

"I am not sure how one could substantiate theories of design "migration" definitively"

and I agree. I also don't know how to definitively substantiate the Theory of

Evolution, yet it seems a fairly sound proposition.

You could probably construct an analogy of gene pools and design pools, isolation

of traits, isolation of motifs, ect., and while it may not constitute a "definative

substantiation" it seems a valid model with which to examine a natural phenomena.

You gotta go with what youv'e got.

I suspect that your rug draws for it's design from a couple of sources, as with

much Turkmen weaving, including flatweaves, feltwork, possibly ikats, and both

a rectalinear and an octalinear design progression. All are just clusters of

characteristics, which seem to express an affinity for an approximate, gross

geographic distribution of designs and techniques. Is there also a temporal

dimension?

Will be back with more soon.

Dave

Posted by David R.E. Hunt on 01-15-2006 03:13 PM:

Central Asian Gulli-Guls

Hi John, James

The following are various incarnations of the Gulli-Gul found in Central Asia

Kirghiz napramach; Kirghiz Gulli-Gul from bagface above;

Karakalpak/Uzbek, from "Black Desert" plate 77; Non-Turkmen, from "Turkmen"

plate 85;

an early Ersari main carpet from "Black Desert" plate 55; an Ersari from "Carpet

Magic" page 37,

an Ersari with the Temirjin gol;

and it's counterpart in a Saryk carpet fragment; "Turkmen" plate 16;

the Salor Gulli-gul; and of course the Tekke.

Interesting, the similarities in construction and drawing found between the

chuval guls above and the Tekke main gul. Could the ubiquitous and stable natures

of these three motives be a function of a kindered history and association?

And of the balance of the Gulli-guls, a more broadly based relationship?

Be sureto check out a thread here on Turkotek, Middle Amu

Darya Weaving, for other apparent examples of design transmission, and from

one medium to another. Scrool about half way down the page (it's a long thread)

to find the referenced material.

Dave

Posted by David R.E. Hunt on 01-19-2006 09:17 PM:

Temporal Dimensions...

Hi James, John

It is important to keep in mind a few basic principals inherent to the study

of Turkestan and in turn Turkmen weaving in general, as postulated by Kalter

in his "Arts And Crafts Of Turkestan".

1. Forms and ornaments which appeared in their characteristic shape for the

first time in the Timurid period have dominated the traditions of the arts and

crafts untill well into our century.(Kalter, pg.39)

2. Items which can be proved to be older than 100 to 150 years are extremely

rare.(Kalter,pg.26)

3. Late medieval cultural traditions have survived untill our own time. This

makes the study of the recent cultures of Turkestan so fertil, but at the same

time so difficult; they can only be understood from a historical point of view.(Kalter,

pg.41)

In short, the cultures of Turkestan have been static since the decay of the

Mongol empires, and it is possible that traditions such as the use of the Palas

as a floor covering and the influences of ikat weaving upon that of pile, may

date to this early period. There is practically no physical evidence, so that

which can be learned must proceed from correlation.

****************************************

A Brief History of Turkestan

Only in the 9th century did independant Islamic states emerge in Turkestan,

at first still formally dependant on the court of the (Arab) Caliph. The most

important of these states, culturally as well as economically, was the Samanid

Empire (874 - 999). The Samanid's capital was Bukhara, their most important

governor's seat was Nishapur.

As documented by tens of thousands of Samanid coins found in Scandanavia, but

also a few scattered ones in Central Europe, Samanid trade, passing via the

Volga basin, reached nearly the whole of europe. The list of export goods made

up by the Arab geographer Mukadasi in the 10th century (Brentjes 1976), is long

and impressive. His (incomplete) list comprises: rugs and prayer rugs from Bukhara

and Samarkand, fine cloths and weavings made from wool, cotton, and silk, soap,

makeup, consecration oil, bows that could only be bent by the strongest men,

swords, armour, stirrups,fittings, saddles,quivers, tents, rasins, sesame, nuts,

honey, sheep, cattle, horses and hawks, iron, sulfer, copper.(Kalter)

Formation of the Turkmen Nation

During the Mongol conquest of Central Asia in the thirteenth century, the Turkmen-Oghuz

of the steppe were pushed from the Syrdariya farther into the Garagum (Russian

spelling Kara Kum) Desert and along the Caspian Sea. Various components were

nominally subject to the Mongol domains in eastern Europe, Central Asia, and

Iran. Until the early sixteenth century, they were concentrated in four main

regions: along the southeastern coast of the Caspian Sea, on the Mangyshlak

Peninsula (on the northeastern Caspian coast), around the Balkan Mountains,

and along the Uzboy River running across north-central Turkmenistan. Many scholars

regard the fourteenth through the sixteenth centuries as the period of the reformulation

of the Turkmen into the tribal groups that exist today. Beginning in the sixteenth

century and continuing into the nineteenth century, large tribal conglomerates

and individual groups migrated east and southeast.

Historical sources indicate the existence of a large tribal union often referred

to as the Salor confederation in the Mangyshlak Peninsula and areas around the

Balkan Mountains. The Salor were one of the few original Oghuz tribes to survive

to modern times. In the late seventeenth century, the union dissolved and the

three senior tribes moved eastward and later southward. The Yomud split into

eastern and western groups, while the Teke moved into the Akhal region along

the Kopetdag Mountains and gradually into the Murgap River basin. The Salor

tribes migrated into the region near the Amu Darya delta in the oasis of Khorazm

south of the Aral Sea, the middle course of the Amu Darya southeast of the Aral

Sea, the Akhal oasis north of present-day Ashgabat and areas along the Kopetdag

bordering Iran, and the Murgap River in present-day southeast Turkmenistan.

Salor groups also live in Turkey, Afghanistan, Uzbekistan, and China.

Much of what we know about the Turkmen from the sixteenth to nineteenth centuries

comes from Uzbek and Persian chronicles that record Turkmen raids and involvement

in the political affairs of their sedentary neighbors. Beginning in the sixteenth

century, most of the Turkmen tribes were divided among two Uzbek principalities:

the Khanate (or amirate) of Khiva (centered along the lower Amu Darya in Khorazm)

and the Khanate of Bukhoro (Bukhara). Uzbek khans and princes of both khanates

customarily enlisted Turkmen military support in their intra- and inter-khanate

struggles and in campaigns against the Persians. Consequently, many Turkmen

tribes migrated closer to the urban centers of the khanates, which came to depend

heavily upon the Turkmen for their military forces. The height of Turkmen influence

in the affairs of their sedentary neighbors came in the eighteenth century,

when on several occasions (1743, 1767-70), the Yomud invaded and controlled

Khorazm. From 1855 to 1867, a series of Yomud rebellions again shook the area.

These hostilities and the punitive raids by Uzbek rulers resulted in the wide

dispersal of the eastern Yomud group. (Library of Congress Country Studies)

Textiles

"The cultivation of cotton, which had origionally been imported from India,had

a centuries old tradition, too. Cotton growing and sericulture (silkworms) were

the foundation on which the flourishing textile workshops in the towns of Turkestan

depended. Cotton has been an important export article since before the Russian

conquest. As early as 1880, the long-fibered American cotton-plant was introduced

by the Russians and areas of cotton cultivation were considerably enlarged.

A great number of irrigation projects, particularlly those carried out after

1920, aimed at the extension of cotton growing. Today, two thirds of the Soviet

Union's cotton harvest is gathered in the Republic of Uzbekistan. Cotton growing

in Turkestan made possible the rise of Russian textile manufacture. As early

as the last decades of the 19th century, cheap Russian cotton printed fabrics

were beginning to supplant the products of the traditional Turkestan textile

workshops more and more, bringing them almost to a standstill, except for the

production of ikat materials with very simple decoration. (Kalter, pg.16)".

Better represented in western collections is ikat, an outstanding product of

Turkestan textile handicrafts. This was put to a variety of uses in Turkestan

households as table cloths, niche curtains, tapestries, bedclothes, covers and

cushion covers.

"According to the literature, in Turkestan, silk and mixed silk/cotton fabrics

are called"abra" or "adra", in Afghanistan (according to Janata), generally

"pardah" (meaning a curtain)."and,

It's exremely varied patterns range from simple stripes to zigzag patterns through

curved lines, to hooks, "cloudband" and circular ornamentation, classic Islamic

motifs such as combinations of stars and crosses, reminescent of Seljuk tiling,

realistic and abstract human figures and trees of life. Despite the credible

work of the important reasearcher in the field of folk textiles, Alfred Buhler,

and an article by A. Janata published in 1978, this fascinating field has barely

been touched in my opinion. The authoritatitive monograph on central Asian ikat

still remains to be written. Buhler assumes- and this

assumption is supported by Janata- that ikat was already produced in Turkestan

in the 8th cent. A.D. The immense number and variety of patterns used in ikat

offer an as yet undeciphered pattern book on which the cultures with which Turkestan

had contact (China,Tibet,India ,Iran) may have left their mark. .

The word "ikat" originated in indonesia. This method of fabric dyeing, like

batik, is a so called "resist" or "reserve" technique, and was developed to

a high degree of perfection there. According to the literature, in Turkestan,

silk and mixed silk/cotton fabrics are called"abra" or "adra", in Afghanistan

(according to Janata), generally "pardah" (meaning a curtain).

To make ikat, the yarn is stretched on the loom. The work is described by Janata

as follows: "In the present case, the threads of the warp are dyed before weaving

by tying them together in bundles according to the desired pattern. A material

of several colors requires several binding and dyeing processes. Since it is

impossible to tie the bundles so tightly that sharp outlines are produced, ikat

weaves can be recognized by the way the colored sections flow in the direction

of the patterned threads. One ikat weave requires the services of nine specialists,

from spinning the silk yarn to weaving. In other places, for simpler products,

fewer sufficed. It is not yet clear who made the ikat fabrics. The repeated

expressed theory that it was made by Jews has not been substantiated. Janata's

conclusion that they were made by Tadzhiks (Arab ethnics) is the most probable,

especially since all the data relating to what craftsmen belonged to which ethnic

groups, indicate most of the craftsmen practising technically sophisticated

crafts were in fact Tadzhiks.

The importance of ikat in urban culture has been described by D. Dupaigne as

follows: Ikat fabrics are luxuries given as gifts of honour at weddings and

other important occasions. The wealth of a landlord or merchant is indicated

by the richness or newness of his garb. The patterns change anually with the

fashion."

P.S. I should note that a recent publication on the subject of ikat, Kate Fitz

Gibbon and Andrew Hale, Ikat: Splendid Silks of Central Asia: the Guido Goldman

Collection (Lawrence King Publishing in Association with Alan Marcuson Publishing,

1999)

***********************************

The following is from a Salon here on Turkotek, The Turkmen

Brocaded Palas as Pile Woven Gul Format Prototype

More Palas

Pictures supplies some interesting comparisons.

Brocade Based Patterns in Turkmen Weaving

Pile woven examples of Palas brocade patterns seem to be straight forward enough,

and there seems to be a high correlation of design elements between the two

groups. Given the propensity for weavers to imitate tile work and engraved patterns,

and in turn for there to be numerous examples of tile and stone engraving imitating

carpet, it seems matter of course that pile floor coverings would imitate the

patterns of brocaded floor coverings as in the palas. That the palas repesents,

as Mr.Slattery contended in the most important "More Palas Pictures" thread

of this salon, "clearly the most basic type of floor covering to be found in

this part of Central Asia" , and in keeping with Kalter's principal #3 above,

which would assert that the palas has been as such since the late middle ages,

further the plausibility that Turkmen gul patterns and symmetry mimic brocaded

Palas patterns and symmetry.

Ikat Weave, from a thread in the above Salon "The Lattice"

It seems that a large number of Turkmen weavings fall into this class, weavings

possessed of patterns and designs which mimic the patterns of ikat cloth, which

itself is so important in this part of the world and which has an extensive

history of production in the Turkmen regions.The size of this class of weavings

speaks much of the importance of ikat, so esteemed and imitated.

The similareties between the two, Ikat and pilework, are many, but this discussion

will center upon two characteristics or qualities of construction and design,

those of warp based design and the symmetry of design.

It is entirely of coincidence that both the ikat and the pile woven rug should

both be of a warp based design structure, in which the design is applied to

the warps by way of dying sections of the warp in ikat, and by attaching dyed

knots of wool to the warp strands in the pile weave. However, it is no coincidence

that the patterns of the two fabrics share the same symmetry, for this characteristic

of being a warp based design both expedites the borrowing of designs and symmetry

and encourage the transaction, by way of simplifying of the process by which

patterns can be transcribed from one medium to the other.

The symmetry of design, between ikat and the pile woven gul format, is perhaps

even better demonstrated by considering the process by which the design is layed

out upon the ikat warps by a technique of halving and folding the warps upon

themselves in order to form a repeating pattern. The following simple demonstration

will clairify this process.

Take an 8 x 11 sheet of standard paper and folds it in half along it's length.

Then fold it again lengthwise. Take the resulting narrow strip and fold it in

half along its narrowest boundry, then fold the resulting rectangle again, across

it's shortest dimension. Now crease the paper heavily upon the edges, and then

unfold it to reveal the perfectly symmetrical grid. The grid which shares the

symmetry of the Turkmen gul format design. Simplicity in itself, this temporal

exercise in design symmetry. Follow this link to another previous discussion

of the ikat/gul

format relationship here on Turkotek.

If you are really a glutton for punishment, check out my other excruciating

Salon, containing some pertinant information regarding Arab cultural inflluences,Streams of

Influence: Motives and Origins of Moroccan Carpet Design.

Dave

Posted by David R.E. Hunt on 01-22-2006 11:25 PM:

East vs. West, Part IV

Hi John, James

Let's return to this east-west dichotomy once again. I had stated above that

"Interesting that Ikat patterns are found abundantly in both Yomud and Ersari

weaving, yet for some reason seem to prevail later in the designs of the Ersari,

Ikat designs being more prevalent in the Yomud during an earlier period(?).

If we are correct in assuming that the Ikat source lies in the east, this would

suggest the yomud were familiar with Ikat and that they traded with the eastern

cities of Turkestan. Perhaps these tendencies, rectalinear vs octalinear, are

more a consequence of geographic isolation due to shifts in trade routes, population

decline, supply/demand, spread of arid regions, ect.."

and seem to have found some correlation in Elena Tsareva's discussion of the

S.M. Dudin collection at Oriental Rug Review

as follows:

Dudin could not study Yomud carpet weaving at this place at the time of the

year. He arrived as the tribe was migrating to summer pastures, and there was

no opportunity to follow them. The only source of rugs were the bazaars of Samarkand

and Merv, neither very rich in Yomud production. So Dudin's impressions of this

group is illustrated only by what was available in the Ferghana Valley.

"Yomud carpets are rarely met at the markets in comparison to Merv or Akhal

Tekkes; most are small pieces, often camel trappings for weddings, asmalyks,

mafrashes, ensis, kapunuks and lastly the runners, yolami.

"In coloring, mainly by common tint and decoration, all articles usually called

Yomud can be divided into several groups. They include products of the Goklan,

Chodor, Ogurjali and so on, and undoubtedly it would be possible to find distinctive

features at least for the most typical objects of these groups if there were

a richer variety of material, at least partly more or less correctly dated."

These two citations from Dudin's article are evidence of the state of knowledge

of Yomud carpet weaving at the eve of the century. Dudin, like most scholars,

could not visit the Yomuds, had no real information on the nature of their weaving,

nor their trade contacts with Iran and the Caucasus. In reality the Yomuds produced

a great number of carpets, mostly in large dimension, for sale. But their markets

were not Samarkand or Bukhara, but the trade centers of the Caucasus and Transcaucasus.

It is known, for example, that it was a question of prestige for Azerbaijanis

to have Turkoman -- or as they were called "velvet" -- carpets in the dowry.

There was some speculation above for the prospect of

"constructing an analogy of gene pools and design pools, isolation of traits,

isolation of motifs, ect., and while it may not constitute a "definative substantiation"

it seems a valid model with which to examine a natural phenomena. You gotta

go with what youv'e got"

and it seems that someone has taken this idea one step further. In their

Investigating cultural evolution through biological phylogenetic

analyses of Turkmen textiles , published in the Journal of Anthropological

Archaeology, Jamshid Tehrani and Mark Collard attempt a statistical analysis

of the frequency of expression, distribution, and filial relationships of design

motives in Turkmen weaving. The following is a sample,

"In contrast to the ethnohistorical evidence, the other two lines of evidence

support the hypothesis of relationships suggested by the textile data. One line

of evidence is the clan names used by the tribes. According to wood (1973),

the Ersari, Saryk, and Salor clan names are derived from an exclusively Oghuz

lexicon, whereas the Tekke and the Yomut clan names include Persian influences.

Moreover, the Ersari, Salor, and Saryk have a number of Oghuz clan names in

common that they do not share with the Tekke or Yomut. Thus, the clan names

support the hypothesis of relationships derived from the textile data, since

they also suggest the Ersari, Salor, and Saryk are more closely related to one

another than any of them is to the Tekke or Yomut. The other line of evidence

that supports the textile data-derived hypothesis of relationships is the geographic

distribution of tribes. As shown in Fig.1, the Ersari, Salor, and Saryk lived

close to the oasisi at Sarakhs and Bokhara, while the Tekke and Yomut lived

in Khorassan. Given the fact that there is a strong statistical tendancy for

territorial groups to coincide with descent groups (Irons,1974), this distribution

supports the suggestion that the Ersari, Salor, and Saryk are more closely related

to one another than any of them is to the Tekke or the Yomut"

of what can be found in this trove of information on Turkmen weaving. While

anyone short of an anthropologist will find much here impenetrable (myself included),

it's interesting, especially in relation to the subject at hand.

Dave

Posted by David R.E. Hunt on 01-27-2006 08:39 PM:

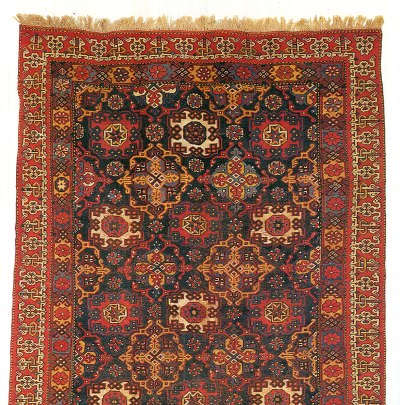

Cavalcade of Ersari Main Carpets

Hi John

Just some scans of Ersari Main carpets. These really are a cornucopia of Turkmen

design

Ersari, from "Carpet Magic" page 37.

Ersari, from "Between Black Desert and Red" plate 55.

Ersari, from "Between Black Desert and Red" plate 56.

Ersari, from "Between Black Desert and Red" plate 57.

Dave

Posted by David R.E. Hunt on 01-30-2006 10:00 AM:

East vs West Part V

Hi John, James

Let's take a look at what Richard E.

Wright has to say about this

engsi.

"Engsis have somewhat different sizes, bear an essentially uniform design, vary

in secondary and minor motifs, and reflect the properties (weave, yarn, color)

alleged (the underpinning links are quite shaky) to characterize the anything

but monolithic principal Turkmen confederations. That these groups employed

a common pattern fits well with their 17th century co-location on the Mangishlak

peninsula prior to having been pushed out by Kalmuks5 and scattered along the

Amu Daria river to the northeast as well as along the base of the Elbruz mountains

(Asgabad and beyond) to the southeast. (Figure 1) The pattern’s persistence

among these subsequently widely scattered and to some extent isolated clans

suggests that the design may be fundamental. There is some thought that it is

old;6 recent carbon dating studies underscore this possibility."

Of primary significance, this statement

"bear an essentially uniform design, vary in secondary and minor motifs, and

reflect the properties (weave, yarn, color) alleged (the underpinning links

are quite shaky) to characterize the anything but monolithic principal Turkmen

confederations"

for it suggests, that just as with these little triangles used as the structural

"building blocks" of rectalimear designs, the engsi format is used by both eastern

and western weavers, and in the case of the engsi, dates to the 17th century.

The significance of last image of a Tekke gul, which hasundergone little change

in the course of it's long history,lies not only in it's being rendered utilizing

these triangular, hence rectalinear building blocks, but especially for thefact

that this rectalinear method is used to realize an octalinear design. Consider

thefollowing

from the thread Hash

Gul Story here on Turkotek, and that notice how the rectalinear "triangle"

units are used to render the fundamentals of an octalinear pattern. I would

suggest that this Hash gul pattern is about as close as you can get to an archtypal

Turkmen design. Even the basic layout, with rows of guls and borders, is rectalinear

in nature.

Be back to finish this soon.

Dave

Posted by David R.E. Hunt on 01-30-2006 10:43 AM:

From the West...

Gantzhorn, ill. 365

Gantzhorn, ill. 367

Gantzhorn, ill. 378

Find above the primary suspect for early Turkmen carpets, produced during a

two hubndred year period spanning the 15th and 17 th centuries. How might these

and the following be related?

Gantzhorn ill.684

Dave

Posted by David R.E. Hunt on 01-30-2006 01:52 PM:

Rise and Fall of Textiles...

Hi John

In their phylogenic analysis above, Tehrani and Collard begin their introduction

by stating that

"The extent to which the evolution of culture is analogous to biological evolution

has been the subject of considerable debate in recent years, as has the corollary

issue of linking patterns in the ethnographic and archaeological records with

and linguistic data"

and conclude with the assertion that

"phylogenesis was the dominant process in the evolution of Turkmen carpet designs

prior to the annexation of their territories, accounting for 70% of the resemblances

among woven assemblages. The analyses also show that phylogenesis was the dominant

process after 1881, although ethnogenesis accounted for an additional 10% of

the resemblances among the assemblages. These results do not support the proposition

that ethnogenesis has always been a more significant process in cultural evolution

than phylogenesis".

Thus it seems fair to generalize that the Turkmen rather more adapt external

design to their own style or method of weaving, than internalize foreign designs

or methods.

Given that they are kindered entities, this dichotomy even extending to language,

( in which the Turkmen speak a West Turkic dialect, and the balance of Uzbek,

Kirghiz, ect., an East Turkestan dialect) is it fair to extropolate from the

Turkmen data that Kirghiz designs are rather more phylogenic than ethnogenic?

And if so, how do we explain the central relationship inherent in these two

primary designs?

Kirghis Gul

Tekke Gul

Yomud Gul

I suggest a model, common to the experiences of both people, Uzbek and Turk,

Eastern and western, and centered around the cities of Turkestan.

Ikat

Remember, that according to Khalter

"Bukhara and Samarkand were cities to equal other centres of the Islamic world

like Cairo, Baghdad, or Isfahan. They belonged to the most important cultural

centers of the Islamic World"

and,

"Due to the political decay of Turkestan and it's shift from the centre of a

huge world empire in the 14th century to an isolated peripheral situation, late

medieval cultural traditions survived untill our own time. This makes the study

of the recent cultures of Turkestan so fertil, but at the same time so difficult;

they can only be understood from a historical point of view",

also

"one has been accustomed to seeing Turkestan as a country on the periphery,

in a dead area of the worlds history. However, this is a late historical development.

During the longest period in it's history which we can consider Turkestan was

a country situated in the centre, a country that was traversed by peoples, merchants,

and armies. This undoubtedly brought a lot of unrest and suffering, but also

long periods of affluence and brilliant culture"

and I suspect this Tekke Guli gul to be a relic of this distant, textile based

culture in which ikat seems to have played a long and important role. With,

as discribed by Khalter,

"It's exremely varied patterns range from simple stripes to zigzag patterns

through curved lines, to hooks, "cloudband" and circular ornamentation, classic

Islamic motifs such as combinations of stars and crosses, reminescent of Seljuk

tiling, realistic and abstract human figures and trees of life"

is the Tekke Gulli gul as seen in the Tekke main carpet design,

an ikat pattern in the form of an arabesque?

Dave

Posted by David R.E. Hunt on 01-30-2006 02:49 PM:

Rectangles vs Octagons

Hi John

But what does all this tell us about this Ersari chuval?

The manner of the drawing,and especially the use of this "triangle" structure

in the chemche gul and elsewhere says to me either a more western geographic

origin, an earlier period of manufacture, or both, as we read from Thompson

above

"The oldest weavings of each tribe frequently provide suprisingly clear evidence

of an early relationship between them in terms of their designs. The further

back we look the more comon ground

we find, which points to a common ancestry for many Turkmen designs. As the

awareness of Turkmen weavings has grown and previously unknown old rugs becomw

available for study, similarities between the tribes emerge that are not evident

in later examples.This suggests that some designs have originated from a common

ancestor at some time in the distant past and that these designs have undergone

successive modifications in the hands of different tribes"

and the unusual devices of the elem say much the same as well. I suspect this

chuval to be an early example of Ersari weaving, based upon the information

I have at my disposal, but it's just an estimate.

Follow this link to a discussion of Ersari Chuvals by David Reuben

Dave

) to photograph, making it challenging to convey the qualities of the colors.

The richness and variability, in accordance to the amount of light, is especially

interesting. Mahogany, Terra cotta, and Tomato are all accurate description

of the ground color under various light conditions. I believe this chuval does

achieve what the color theorists characterize as color harmony, as it can be

argued to demonstrate:

) to photograph, making it challenging to convey the qualities of the colors.

The richness and variability, in accordance to the amount of light, is especially

interesting. Mahogany, Terra cotta, and Tomato are all accurate description

of the ground color under various light conditions. I believe this chuval does

achieve what the color theorists characterize as color harmony, as it can be

argued to demonstrate: