Posted by John_Lewis on 04-07-2005 12:42 AM:

Some questions on Turkmen Prototype

The hypothesis is surely incapable of being proved or disproved?

We

know so little about Turkmen weaving that the only evidence we have as to

whether the chicken or the egg came first is the evidence of available pieces.

Scientists are allowed theories (as are rug enthusiasts) but there must be -

eventually - evidence to support those theories, otherwise we must discard them,

or hold them as beliefs (e.g. Christian creation). So, here are some questions

that can be used to help test the hypothesis. I pose them because I do not know

the answers.

1 What is the age of the earliest known Turkmen pile pieces?

(1600?)

2 What is the age of the earliest known not-piled pieces - call

them kelim for simplicity? (i.e. are there any earlier than 1 above?)

3

What is the age of the earliest known non-Turkmen kelim?

4 What are the

"survivability rates" i.e. how MANY 1600/1700/1800 Turkmen pile pieces are there

around today (the members of this forum should be able to make educated guesses

- produce a histogram)

5 Ditto the survivability rates for non-piled

Turkmen pieces.

6 How does the "survivability rate" compare with other

weaving cultures.

7 Is there any support for the hypothesis from

"predictive archeology"

When we have answers to these questions we still

will not "know", but I suspect the quantitative data (even though they are

guesstimates) will not provide any evidence to support the

hypothesis.

regards

Posted by Steve Price on 04-07-2005 11:42 AM:

Hi John

Thanks for your very thoughtful, and thought provoking,

questions. I will try to get us started:

1 What is the age of the

earliest known Turkmen pile pieces? (1600?)

There is a Tekke juval (pile

face) that has been carbon-14 dated to 1650. Some people believe this to be a

reliable result, others (including me, which isn't proof of anything) reject it

for a number of reasons.

2 What is the age of the earliest known

not-piled pieces - call them kelim for simplicity? (i.e. are there any earlier

than 1 above?)

I assume that you refer specifically to Turkmen. Most

people don't even try to make date attributions of Turkmen flatweaves beyond

noting the presence or absence of dyes that are obviously synthetic. For that

reason, I don't think there is a meaningful answer to this question.

3 What is the age of the earliest known non-Turkmen

kelim?

There are very old flatweaves from Andean caves, frozen for many

centuries. I don't recall the estimated ages, but I think you're really looking

for central and western Asian examples anyway. There are carbonized fragments of

what appear to be tapestry woven fabrics in central Turkey (Catal Huyuk) dated

to about 7,000 BC. The Victoria and Albert Museum (London) has a kilim fragment

estimated to date to about 700 AD, and I believe that this is the oldest known

example.

4 What are the "survivability rates" i.e. how MANY

1600/1700/1800 Turkmen pile pieces are there around today (the members of this

forum should be able to make educated guesses - produce a histogram).

It

seems self-evident that the extant Turkmen pieces include large numbers of

recent weavings, progressively smaller numbers as we go back in time, eventually

reaching the point from which there are none left. Putting numbers on the

various time points is hardly more than guesswork, since there are no reasonably

reliable criteria by which date attributions earlier than, say, 1800 can be made

for Turkmen weavings (at least, in my opinion). Some authors are pretty

aggressive about date attribution, and Siawasch Azadi attributes about 10% of

the pieces in WIE BLUMEN IN DER WUSTE as pre-1800.

5 Ditto the

survivability rates for non-piled Turkmen pieces.

See the answer to

question number 2 for why I think this one is

unanswerable.

Regards

Steve Price

Posted by John Lewis on 04-07-2005 06:30 PM:

Is it really that difficult?

I like to keep things simple, so if a reputable laboratory Carbon dates a rug

to around 1650, I can accept that, since C-14 dating is a fairly reliable

technique in that range.

I agree that dating Turkmen pieces before 1800

is difficult but you can probably get some consensus around bands i.e. before

1800, 18Q1, Q2, Q3, Q4, 1900 and later. I don't think anyone believes that

Turkmen did not start pile weaving until 1800 (do they?), so the deduction is

that there is a high degree of Turkmen design integrity between 1650 and 1800.

Turkmen were weaving pile pieces in that period - but they just did not change

much. I know that some Turkmen experts believe they can date pieces to a much

finer granularity (they have tried to sell them to me as such), but the above

will do for us mere mortals and for the purposes of the thought

experiment.

So, how many Turkmen kelim pieces have the forum members seen

that you would place before 1850? (bearing in mind that the design features

should not be discernable in contemporaneous pile weavings). I suspect not many.

Personally, I have seen none - I would certainly like to see any examples that

anyone has.

There are a LOT of kelim pieces dated to before 1850 from

other weaving cultures (at least I remember seing an article in Hali with a

number of early datings).

So, (jumping ahead), why are there so few pre

1850 Turkmen kelims - why is their survivability rate so low in comparison with

other weaving cultures?

Here is another hypothesis, Turkmen used simple

(quick) weaving for utilitarian items, and reserved pile (slow) weaving for

"special" items. There is no temporal link between kelim and pile

motifs.

This is also incapable of being proved or disproved, is therefore

a belief, and equally valid.

regards

Posted by David R.E. Hunt on 04-07-2005 09:57 PM:

John, Steve, All

First, thanks Steve for the detailed response. Sorry

for taking a while to get back, am suddenly quite busy.

Permanence of

design of the palas is the

primary, distinguishing characteristic of the

class.

The evidence from symmetry is obvious in my opinion, and singular.

You are not in the least bit interested or curious

as to why so many of

these palas were made and why they are so similar?

Besides you

state

"Turkmen used simple (quick) weaving for utilitarian items, and

reserved pile (slow) weaving for "special" items."

There are numerous

examples of these palas bags made

with silk.

You have been disproven all

ready

My "theory" would

not discount that this relationship

of symmetry,between palas and pile, could

lie in a third

weaving medium, say silk or damask loom.

In short I do

believe there is much circumstantiaal

evidence,and much real, tangible

evidence of a relationship.

Check the Archtype/prototype thread for an

article

by Marla Mallett regarding Archtypes and technique generated

designs.

On one hand you state their utilitarian pedigree, and on the

other are

non plused by a lack, percieved or real, of elderly

pieces?

I have heard this term earlier, "predictive archaeology",

and

take it to mean speculation? Both R.J. Howe And

Ali R. Tuna have offered some

speculation upon the

subject of Turkmen pile weave having designs

generated by slit weave and Zili weave respectively,

but I don't believe

this to be anathama to my premise, for pileweave

designs could be and were

borrowed from other weave

techniques. They could well constitue important

contributions to the

repetoir of an experienced weaver, several varieties

used in a single weaving.

Given pile weave versatility, this would be

expected.

I

would consider the introduction of foreign weave techniques

evidenced as such

by this palas with the zili border,

as constituting a seperate branch of the

typology "tree"

if you will, and evidence of a degree of seperation from

the

primary border format, with it's double kochak medallion.

The elems, with the

respective flatweave/blue lines of the former and

"proto medallions" of the

latter might also represent differing classes as well.

An overall red or

blue/green tonality might also constitute

two groups respectively, evidence

of varying tribal

affiliation?

While much is infered, much real

evidence exists in

this huge body of woven product so uniform and

so

constant, even more so than Turkmen pile weaving itself,

in all it's

constancy and uniformity.

Turkmen weaving are the product of a singular

time

and singular peolpes, and those distinguishing

characteristics of

their weaving are as singular.

In concluding, John states

that

"There is no temporal link between kelim and pile motifs.

This is

also incapable of being proved or disproved, is therefore a belief, and equally

valid."

While we are all entitled to our opinions, I honestly

believe

there to a temporal link between pile and flatweave, possibly

an

important link. Johns conclusions, I believe, are based upon a class

of

speculative and unsubstantiated assumptions regarding

the palas. My

observations are of a real and naturally

defined class of weaving and it's

relations to others,

and while the understanding of these relationships may

be

imperfect, there is more to them than assumption.

While I cannot

discount it completely, I find John's

argument

unconvincing.

Dave

Posted by John Lewis on 04-08-2005 07:02 AM:

English politeness

David,

I was very politely (the English way) making the point that you

have offered no proof of your hypothesis and that until you do, that is all it

is.

Furthermore, I was making the point that anyone (even someone as

uneducated as I am) can dream-up hypotheses, but it doesn't mean they have any

value. Like yours, they may be merely beliefs.

To give your hypothesis

more weight you need to

1 Show early examples of Turkmen non-pile

weavings. It would be nice to see a date estimate for each of them.

2

Show examples (plural) of later pile weavings that show the same non-pile design

elements (and where earlier pile examples do not exist).

If you can do

that (and you have not done so to date), then your hypothesis has some value (it

COULD be correct). If not, then it is merely a belief.

My scepticism

stems from not having seen many early Turkmen non-pile pieces, and from finding

alternative hypotheses for the origin of Turkmen design motifs far more

convincing (but also merely hypotheses).

I do not regard myself as an

expert in rugs, but I know scientific rigour when I see it, and I am not seeing

it.

Einstein believed that "God does not play dice", but scientific

rigour shows that he seems to.

regards

Posted by Steve Price on 04-08-2005 08:17 AM:

Hi John

You raise two basic issues here:

1. You are not

convinced that flatweaves were made by Turkmen more than, perhaps 100 or 150

years ago. I'm not either, for the same reasons.

2. You take the position

that hypotheses without a lot of evidence behind them are of no value. I

disagree, and will devote the rest of this post to my reasons.

A

hypothesis is simply a straw man - an idea or a speculation. It is tested by

framing questions that lead to observations which will either contradict or be

consistent with it. When it passes a number of tests, we feel more comfortable

about the likelihood that it is correct. When if fails some, we reject it. But

usually, the failed tests lead to refinements in our thinking - better (or, at

least, alternative) hypotheses. That is, hypotheses are not useless by virtue of

being incorrect or speculative, they are the road to progress. Proof, in

principle, is unattainable. In scientific terms, failure to disprove by many

independent means is as close to proof as you can get.

A hypothesis is

useless if it is of such a nature that it is impossible to make an observation

that would be inconsistent with it, even in principle. In the peculiar world of

scientific truth, such a hypothesis is regarded as incorrect. An example is that

the explanation for some phenomenon is that it is a miracle. By definition, a

miracle is outside of natural law, so it cannot be put to a test by any means

within natural law. The formal scientific position, for that reason, is that it

is never acceptable as a useful hypothesis and is never acceptable as a correct

explanation. There are other problems with accepting it within the method of

truth testing that we refer to as science, but that takes us further afield than

we need to go here.

To return to Dave's hypothesis, it is useful

precisely because it is possible to frame questions (like the ones you raised)

that bear on the probability that it is correct.

Regards

Steve

Price

Posted by John Lewis on 04-08-2005 03:58 PM:

So you agree with me?

Hi Steve,

You seem to be agreeing with me about the lack of Turkmen

flatweaves before 1850. I do not know whether it is because they never wove them

(decorative ones - they clearly wove non-decorative ones) or because they wove

them but few have survived (seems unlikely). Are we in a minority of 2 or do

other people out there have evidence of early Turkmen flatweaves? Perhaps a

collector has cornered the market?

Yes, hypotheses have uses, but an

hypothesis that has little evidence to support it does not have much use. It is

the responsibility of the person putting the hypothesis forward to ensure it is

reasonable. That is why I am asking to see some evidence and look forward to

seeing the answers to my questions.

There are quite a lot of hypotheses

about Turkmen weavings, some have merit, some probably don't and we need to sort

the wheat from the chaff.

I realise that studying rugs is not a

scientific discipline, and never will be, but surely your forum expects some

degree of rigour.

regards

Posted by Steve Price on 04-08-2005 04:19 PM:

Hi John

Dave presents several hypotheses:

1. The designs on

Turkmen palas are technique-generated (in the sense that Marla Mallett means,

for example).

2. The designs on Turkmen palas are the ancestors of some

motifs on Turkmen pile weavings.

The second hypothesis has another

embedded within it - that the palas designs arose before those on the pile

weavings did.

I know of no examples of Turkmen palas that predate 1850.

This does not help hypothesis number 2, although (as you note) it doesn't

destroy it altogether. But it does suggest an alternative - that the motifs on

the pile weaves are the ancestors of those on the palas. That, in turn, bears on

hypothesis number 1.

I don't think Dave's hypotheses, in their original

form, are unreasonable. They are subject to various kinds of tests and the

outcomes of those tests suggest alternative hypotheses. That is, even if they

turn out to be incorrect, they advance our thinking and force us to re-examine

some of our beliefs. Most hypotheses are incorrect, although it takes longer to

discover that with some than with others. Newton's laws of motion progressed all

the way from half-baked idea to hypothesis to theory to law before it was

discovered that they were not quite correct.

Turkotek isn't a

professional organization, it's a discussion forum through which enthusiastic

amateurs can extend their understanding and sharpen up their partially baked

ideas by subjecting them to public scrutiny.

You have to kiss a lot of

frogs before you find Prince Charming.

Regards

Steve Price

Posted by John Lewis on 04-08-2005 06:16 PM:

Stoned Frogs

Hi Steve,

You must have some English blood in you because to say "This

does not help hypothesis number 2" is called English understatement.

It

does not make Myra Mallet's assertion incorrect though (and I am not addressing

that); that stands by itself, but it goes to the heart of David's

hypothesis.

I have another hypothesis. That the Turkmen weavers were

stoned a lot of the time. I jest not - there is evidence for this one

1 I

have lined up several of my old (18Q2 and earlier) chuvals after having smoked a

joint and there is no doubt that dimensionality (see Jim Allen's articles)

increases. They "wave in the wind". (OK - not "evidence" but observable - from a

particular frame of reference)

2 There is evidence that Turkmen did

partake.

3 Many Turkmen pieces contain silly "mistakes" that no careful

(not stoned) weaver would make.

4 Turkmen women laugh a lot and are very

forward (contemporary writings).

Also, put yourself in their position. if

you were stuck in the middle of nowhere with a bunch of children, had to weave

for 4 hours a day, and your husband stank - you would probably want to smoke (or

eat brownies)! (situational analysis)

As for "predictive archeology"

testing some old unwashed chuvals for cannaboids might be

instructive.

Please do not respond to my hypothesis in this thread

because it will deflect from the main discussion, but I do believe it is at

least as worthy of a Salon. Perhaps we should get a "lock in" at the Hali fair

one evening and conduct an experiment?

However, back to the main topic, I

am open-minded and my comments should be taken in the spirit in which they are

intended (wanting to move rug scholarship forward but essentially realising that

it is not important); it is just that a little bit of evidence to support

David's hypothesis would be nice.

regards

Posted by Steve Price on 04-09-2005 06:34 AM:

Hi John

Actually, when I said that not having any early specimens

didn't help Dave's hypothesis, that was what I meant. There are, as you

recognized, several alternative explanations for their absence. These

include

1. there never were any (which would be fatal to hypothesis number

2);

2. there were some, but they are gone because collectors didn't want them

and Turkmen didn't value them;

3. there are some now, but we don't know how

to identify them.

There are other kinds of Turkmen things that don't seem

to include early examples, and we might look to those for guidance.

1. Prayer

rugs: Except for the Beshir group, few - maybe none - predate the mid-19th

century. Given the popularity of prayer rugs among 18th and 19th century

Europeans, and the fairly gentle use to which prayer rugs are subjected, it

seems very likely that early examples made by Turkmen other than those settled

in cities never existed.

2. Khorjin: If made they would have been subjected

to harsh conditions, so the absence of early examples may not mean that there

never were any. There are specimens from every major Turkmen group except the

Salor, so if we believe that they were not produced until, say, 1875 or so by

any Turkmen, we are forced to hypothesize that every Turkmen group began weaving

them more or less simultaneously. I find this difficult to accept.

Back

to Turkmen palas. Why don't we have a bunch of early 19th century (and older)

specimens? I don't think there's an answer that jumps out and makes every

alternative go away, and the fact that we might not recognize one if we saw it

is a serious problem.

I find Dave's observation of what appears to be a

relationship between certain motifs on Turkmen pile weaves and the designs on

Turkmen palas to be interesting and worth thinking about.

Regards

Steve Price

Posted by John Lewis on 04-09-2005 02:01 PM:

Whilst we are waiting

Hi Steve,

Whilst we are waiting for David to reply with some evidence

to support his hypothesis - as an aside, you say “Turkotek isn't a professional

organization, it's a discussion forum through which enthusiastic amateurs can

extend their understanding and sharpen up their partially baked ideas by

subjecting them to public scrutiny.”

That sounds good – there is always

room for enthusiastic amateurs – Einstein was a Patent agent. So who are “the

professionals” that we should look to for guidance on Turkmen weaving? Is it the

dealers – Jim Allen, Jack Cassin, Michael Craycraft, David Rueben etc.?

Who?

I am a collector; I have never sold a piece in my life. I would like

to “sit at the feet” of real Turkmen experts and learn. In the meantime I am

reading as widely as I can and looking at a lot of pieces.

I note that

some mathematical/scientific techniques have been brought to bear (Jim Allen on

the dimensionality of guls) and I have seen the word “symmetry” used in the

Turkotek forum. Was this meant in the mathematical context (Point Groups)? I

have never seen an early (before 1850) Turkmen piece that exhibits symmetry.

Individual design elements possess symmetry, but never the entire piece. Not one

single piece in my collection exhibits even C2 symmetry. Does the forum have any

mathematicians or symmetry experts who have undertaken a formal study of

symmetry (or lack of it) in early Turkmen pieces?

I know that Islam

prohibits perfection, but from everything I have read, I cannot find any

evidence that the nomadic Turkmen were very Islamic (on the contrary). In the UK

less than one person in 60 goes to church on a Sunday – I suspect Turkmen

Islamic observance was even less. Shamanism seems most prevalent. This would

explain the absence of prayer rugs.

You are the moderator and I do not

want to deflect this thread from its main discussion. I suspect the above must

have been raised before so I am wading through your archives, but any pointers

would be welcome.

regards

Posted by Steve Price on 04-09-2005 04:04 PM:

Hi John

All the points you raise are well within the range of

digressions we normally encounter. That's part of what makes discussion

interesting.

Who are the professionals in the world of rugs? Academic

professionals would be people on museum staffs, in university departments of art

history, Islamic studies, anthropology, etc. Some of them participate from time

to time (Peter Andrews comes to mind as an example of a card-carrying academic

expert on Turkmen who sometimes shares his expertise with us). Many dealers and

collectors have acquired significant levels of expertise in specific areas. Some

have made contributions to our understanding, some have contributed useful

hypotheses (useful in the sense that they can be tested and refined). Many, in

my opinion, have created more heat than light.

This isn't to say that a

community like this one lacks expertise. The participants include experts in

areas that can be brought to bear on questions related to rugs. If you browse

our archived discussions and essays, you'll find input from weavers, artists,

musicians, composers, professional dyers, rug repair people, museum

professionals, scientists of every stripe, mathematicians, and on and on and on.

Some of the discussions bear characteristics of sound interdisciplinary research

efforts.

Carol Bier, at times in collaboration with Wendel Swan, has

presented some thoughts on symmetry, although I don't believe she has addressed

the matter in Turkmen weavings.

Regards

Steve Price

Posted by Tim Adam on 04-10-2005 12:54 AM:

Hi John,

I very much appreciate your thoughtful posts in this thread.

After reading Marla Mallet's discussion on design origin, I think the idea that

certain design elements on Turkmen palas are technique-related, and that they

have been copied onto pile pieces is entirely believable. After all, they are

really Marla's hypotheses, and we are just trying to apply her ideas to Turkman

palas and pile weavings.

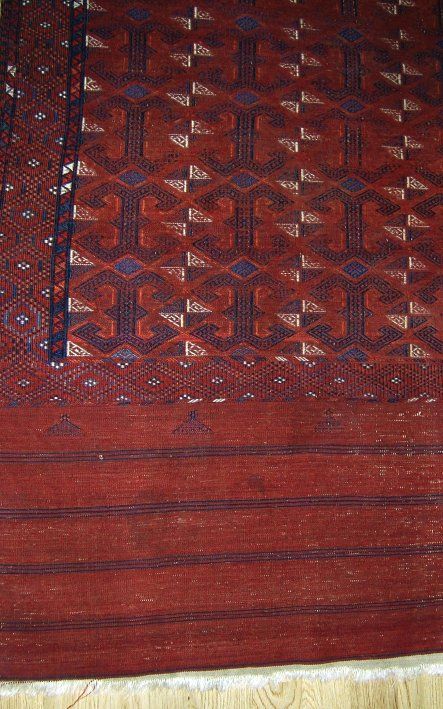

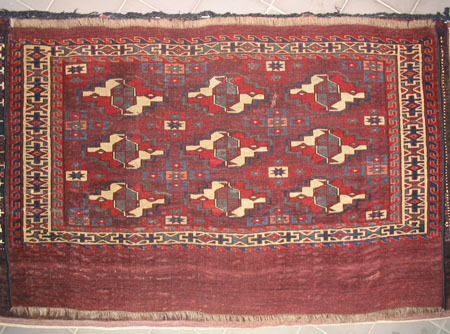

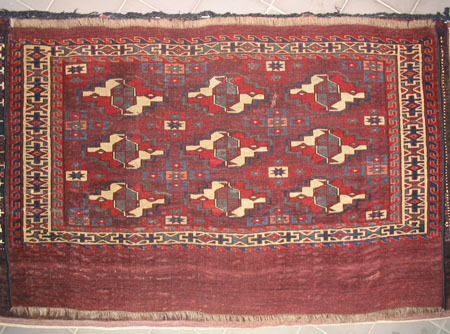

The pieces that have been posted so far, which

I find most convincing in displaying a relation to flatweaves, are the

following.

I think the

significance of the first piece lies in the pattern of the interior of the

double kotchak motive. This sort of pattern is, I believe, technique-induced,

but not necessary for pile weavings. The same applies to the border of the Salor

torba, which mimics a zili technique, as pointed out by Ali in a different

thread.

The idea that palas designs arose before those on pile weavings

is essentially not testable in my

opinion.

Regards,

Tim

P.S.: I love your “stoned weaver”

hypothesis.

Posted by Tim Adam on 04-10-2005 01:04 AM:

Symmetry

John,

There is an interesting web page by mathematicians on design

symmetries in rugs.

http://mathforum.org/geometry/rugs/

You wrote, "I

have never seen an early (before 1850) Turkmen piece that exhibits symmetry."

How strictly do you mean that? For example, if the undecorated elem of a torba

is a bit longer than the top of the piece, does that already break the symmetry

that you are talking about? What if the corner resolutions of the border is not

perfect? If those are ok, I could show a piece that has 'perfect'

symmetry.

Tim

Posted by Steve Price on 04-10-2005 07:41 AM:

Hi Tim

The website you linked is the symmetry paper written by Carol

Bier. Although I didn't remember Turkmen textiles being addressed specifically,

she uses them for a number of examples.

I don't know how far I'd take

John Lewis's statement about older Turkmen things being invariably asymmetric,

but my impression is that they are usually asymmetric in more obvious ways than

younger ones are. Pentagonal Yomud asmalyks with lattice fields are good

examples, since their apices are more or less dead center. Older ones seem

invariably to have the lattice off center; younger ones seem always to have it

centered.

Regards,

Steve Price

Posted by John Lewis on 04-10-2005 09:08 AM:

comments on pieces and symmetry

Hi Tim,

You say "The idea that palas designs arose before those on

pile weavings is essentially not testable in my opinion."

I agree 100%.

For David's hypothesis to have some credibility then the non-woven pieces need

to have some age. The first piece you show looks modern (after 1900?). The

second piece - the kedjebe - is a pile piece with woven elem and does not, I

think, add much support to the argument - it certainly is not a prototype of a

pile woven gul format.

I am not saying early pieces do not have

symmetry, just I have not seen any - and I am not being too strict i.e. exact

dimensions. It doesn't mean they do not exist - though sometimes one needs to

look at a piece for quite a long time before some of the features "grab you". I

have a few rugs hanging around my sitting room and noticed a feature I had not

spotted before on one only the other day.

regards

Posted by Steve Price on 04-10-2005 09:39 AM:

Hi John

Having some very old palas specimens would surely strengthen

the hypothesis that some gul motifs evolved from palas designs, and would

eliminate it if we knew that the reason we have no early palas is that there

never were any. We don't know that, though.

I'm skeptical about the

likelihood that palas design is an ancestor of pile motifs, but their familial

relationship is striking. My inclination is to think that they both derive from

a common ancestral pool, that pool being

technique-driven.

Regards

Steve Price

Posted by Tim Adam on 04-10-2005 11:12 AM:

Hi John,

I think I wasn't clear in my previous post, or I completely

misunderstand Marla's explanation of design transmission.

The point is (I

think) that the particular way the double kotchak motive of the first piece is

done - the dots that fill out the kotchak - suggests a brocade origin, because

if you do a double kotchak as a brocade, you have to fill the positive space

with something, otherwise it won't be good. If the pile piece is say 1900, then

the inference is that in 1900 the weaver copied this kotchak from a Palas for

example.

The Zili style border of the Salor Torba is the same. Since it

is much older, we can infer that flatweaves have been around much

longer.

So, if we believe in Marla's hypothesis, we need look at the

oldest possible pile pieces for evidence of designs that may have a flatweave

origin. That could gives us clues about since when flatweaves have been

around.

All this does not say anything about the origin of the kotchak

motive itself, or any of the guls that Dave mentioned in his

salon.

Regards,

Tim

Posted by Tim Adam on 04-10-2005 11:14 AM:

John,

Regarding symmetry, what do you think of the following

piece?

Tim

Posted by Louis Dubreuil on 04-10-2005 12:15 PM:

Early turkmen flat weavings ?

Bonjour à tous

In his book"treasures of the black tent" Brian Mac

Donald describes (page 18) the dowry work of the turkmen girls in XIX° century.

In this listing there is neither kordjins (double saddle bags) nor palas. We

find : ghali, dip ghali, engsi, kapunuk, germetch, twelve mafrash and torbas,

two large cuvals, two uk bash, two asmalyks, three ak yup (tent band), and one

namad (felt rug). There is also no prayer rug (joy namaz) in this list.

I do

not know the origin of this list and at what tribe it is associated (maybe

tekke, as it was the well known tribe).

There is no palas in this list.

Remeber that the word palas has a signification of low value textile.

The

use of palas is an everyday use on the yurt ground. This fact can easily explain

that those items are periodically replaced and that there are no antique

examples left. I suppose also there are no namad left from XIX° c. It is the

same think with the special carpets made to be disposed arround the fireplace

(ok shash bashi), there are very few of this type of rugs in the

collections.

The list above is the "dowry list". Items made for this

purpose are generally verywell made and are used to the yurt embellishment.

Those items are well protected and generally well stored and not daily used.

This is the reason why we can find very old examples of those dowry items,

especially of the more precious and easily "storable", like torbas or asmalyks.

I think it is the same phenomenon than for the silk ikat dresses of uzbekistan.

We have very old examples of them because these dresses were preciously stored

in family chests for generations.

We have questions about turkmen

kordjins. No antique examples known. But do we have antique examples (earlier

XIX°) of kordjins made by any other tribe? Kordjins, contrary to dowry chuvals

or torbas, were everyday-use items and the turn-over must be very fast. When we

consider yomut chuvals, for exemple, we have piled ones that can be very old,

and flat woven that seem to be more recent. I think this is why piled ones are

more priced (by family and, after by the market) and more cautiously stored than

flat woven ones that are daily used for heavy duty works. We have the same

phenomenon with ak yup : piled ones are very well preserved, flatwoven ones,

when they are antiques are always fragmented.

For the same reasons I

think that the design of the flat wowen turkmen items are more archaic and more

stable because they are not dowry items. When a young girl makes her dowry work

she had to prove her technical and artistic skill, whithin the standards of the

design's tribe, but with a little possibility for the better to make certain

evolutions of the design and to follow the fashion. This evolutive process has

increased whith the opening of the tribes to the market in the middle of the XIX

century.

For utilitary items as palas or flatwoven bags the making has to

follow two principles : being less time, and less wool consuming than piled

weavings, being consistent with the standards of the tribe (use of ancient

apotropaïc designs in order to protect the goods and the family). In this type

of work there is no place and no reason for improvisation : they are not made

for pleasure but just for necessity. This is why we find in utilitary items more

archaic features than in dowry items. And why those designs are shared by

severals peoples (with a old common origin) spread over a large territory

(anatolia, turkestan). This is why we can find for example, the same design in

neolitic artifacts and on contemporary weavings in the High Atals

area.

To resume : we have two process in making woven artifacts. A

conservative process for utilitary less time/wool consuming items (kilim, zili,

soumak, plain wave) whitch have the tendancy to "fossilize" the design that

remains mostly archaic and that we can find with very little variations amongst

lots of peoples of the same old origin.

An evolutive process for dowry items

: designs can evolve quite fast and designs can diverge and become different

from ancient prototypes. In this case each tribe (or each family) each

design.

There are certainly the same "root" designs shared by flatwoven

and piled items but there has been sometime an old divergence (like between

chimpanzes and us) that has made them now quite different.

Louis

Dubreuil

Posted by John Lewis on 04-10-2005 02:04 PM:

Symmetry of Yomud Chuval

Hi Tim,

There is no C2 symmetry in the piece.

The borders have

one set of symmetries and the main field another.

There are a few "Stoned

weaver" mistakes in the borders that break it - but lets ignore

those.

However, the most intersting (to me) break in symmetry cannot

easily be seen in the piece - that needs you to measure the height of the guls.

In a piece of such small size - the height of the guls (the dimensonality that

Jim Allen has measured).

What is your date estimate?

regards

Posted by Filiberto Boncompagni on 04-10-2005 02:37 PM:

Hi Louis,

Interesting observations. I had a look at the catalog of the

exhibition “ Carpets of Central Asian Nomads – from the collection of the

Russian Museum of Ethnography, St. Petersburg” organized in Genoa in 1993.

It shows a lot of utilitarian items, but few flatweaves: a wedding curtain,

a koshma (felt floor cover) and a rather perishable eshyk-tysh

(reed door hanging). No palas.

quote:

Remember that the word palas has a signification of low value textile.

Well, “palas” is a term I always found associated with

Caucasian flatwaves. Perhaps it’s an Armenian word, I’m not sure about it. Does

Parvis Tanavoli's book say anything about the etymology of “palas”?

I’m

wondering if the reason why there are not old palas could be that the production

of palas is quite recent. One proof could be that Turkmen had no name for it and

had to borrow it from another location/language.

This doesn’t explain the

absence of other kinds of old flatweaves,

anyway.

Regards,

Filiberto

Posted by John_Lewis on 04-10-2005 03:01 PM:

Comments on posts

Hi,

Steve says, "My inclination is to think that they both derive from

a common ancestral pool, that pool being technique-driven."

Louis makes a

similar comment "There are certainly the same "root" designs shared by flatwoven

and piled items but there has been sometime an old divergence (like between

chimpanzes and us) that has made them now quite different."

That may be,

but if you both belive that you contradict David's hypothesis which is that the

guls are DERIVED from the palas designs.

I have three comments

1 I

suspect the ancestral pool of designs is not "technique driven" the designs are

designs - period. They just happen to be implemented in an available technique

(and the technique causes them to diverge).

2 Kelims were used in lots of

other cultures as floor coverings yet lots of examples of old ones from other

cultures exist. I am not making an hypothesis, merely commenting that it seems

strange.

3 Taking a comment from Tim. The design on the Salor kedjebe

could be from earlier Salor pieces - there are two in the Sotheby catalogue of

the Thompson sale and several more are referenced. There is no evidence they

derived from palas (is there?)

regards

Posted by Steve Price on 04-10-2005 04:02 PM:

Hi John

I do not believe that it is likely that guls derived from

palas designs - I thought I made that fairly clear several times, but I guess I

didn't. I do think that the ease with which one can modify one to get the other

suggests a common ancestor for both, which is also how I interpret Louis'

comment.

Many of the surviving very old kilims were floor coverings in

mosques, where they were not exposed to much light and never subjected to the

kind of foot traffic that might be expected in a yurt. Couple this to the

disinterest collectors have long maintained in Turkmen palas, and I'm left not

terribly bothered by the fact that there are lots of very old kilims, and not

many very old palas.

You raise the hypothesis that dimensionality in

Turkmen weavings is correlated with age. I don't want to revisit that topic in

much detail, but the total amount of evidence supporting it is a mathematical

measure of dimensionality in two juvals that had both been dated by C-14. Even

if you believe that C-14 is useful for this purpose (I don't think it is, but

that isn't important), the two pieces are not significantly different in age in

the statistical sense - the mean age estimates differ but there is a reasonable

likelihood that the one with the "younger" date is actually older. Furthermore,

no conclusions are possible from comparisons involving only two samples.

Regards

Steve Price

Posted by John Lewis on 04-10-2005 05:19 PM:

Dimensionality

Hi Steve,

It is OK, I understood you the first time - (that YOU don't

believe guls are derived from palas designs) - but it is David's hypothesis, so

I am awaiting his response.

I read Jim Allen's paper on dimensionality. I

do not know whether "dimensionality" increases with age - but I have observed

that very old (18Q2 and earlier) yomud chuvals tend to have a variation in gul

height which creates (especially when viewed when stoned), a 3 dimensional

effect - they "wave in the wind". (Please, dear reader, do not try this at home

without medical permission, or if you do, it is entirely at your own risk). It

seems you have previously had a discussion on this topic and I only raised it in

response to the symmetry question. The height difference does not seem to be

accidental or due to poor weaving technique.

regards

Posted by Steve Price on 04-10-2005 06:00 PM:

Hi John

As you noticed, although I don't think it likely that palas

designs were the ancestors of Turkmen guls, I do think that it is likely that

they share a common ancestor. This is something that I would describe as a

worthwhile result of examining the original hypothesis. Replacing one hypothesis

with another in the face of evidence or argument is pretty much how science

works and makes progress. The important question is not who believes it (that

is, it matters not one whit whether Dave does or I do or you do), but where it

leads.

My take on the matter is this: there is nearly nothing written

about Turkmen palas, especially about the origins of their designs. By

introducing the subject with some provocative ideas, Dave has gotten the subject

off square one with an observation that I believe is novel. It is potentially

important, and I'm neither shocked nor surprised to find that the hypothesis

that he based on that observation is weaker following discussion and is being

replaced by a better one. That isn't failure, it's success.

When you are

stoned you can clearly see a three dimensional effect in gul height of Turkmen

pile weavings? This doesn't even rise to the level of anecdotal evidence. How

about some data, like the relative dimensions of each row of guls in a

substantial number of pieces selected by some randomized procedure, with

reasonably well documented ages?

Regards

Steve Price

Posted by John Lewis on 04-10-2005 07:42 PM:

Last post

Hi Steve,

In replacing David’s hypothesis with one of your own, I

assume that you are willing to defend it? Personally, I do not agree with your

hypothesis either but that is not for this thread.

As I said earlier, if

one is putting forward a hypothesis, there has to be some evidence to support

it. What evidence is there that palas designs and guls share a common ancestry

(Are you using guls as in David Rueben’s gols and guls) or to mean the main

ornament?

As for the observations about dimensionality - this is not a

new idea, it was proposed by Jim Allen. The differing height of guls is clearly

visible in my own collection. If, (to get an adequate sample size) the Turkotek

participants measure the gul height on old (18Q2 and earlier) Yomud chuvals they

will (I am sure) find differences between the rows. Later chuvals are more

consistent. The observation that this 3D effect is enhanced when stoned is

simply an observation, my own – from an observer in a different frame of

reference!

Whether the dimensionality increases with increasing age is

moot.

regards

Posted by Steve Price on 04-10-2005 08:45 PM:

Hi John

Dave's illustrations of how little it takes to transform some

Turkmen pile motifs to (or from) some palas designs suggests that they are

related. Some possible relationships include the one Dave proposed - that the

palas designs are the ancestors of those pile motifs. Another is that the pile

motifs are the ancestors of the palas designs (I believe Vincent Keers

introduced that one), about which I'd feel better if there was a way to be

reasonably certain that the palas is a recent development. The third is that

both have a common ancestor. That's all the support that I have for my

suspicion, but I do think the matter is worth thought about how it could be

pursued when time permits and suffices for purposes of putting it into a

conversation (which is really all this is).

There is no argument from me

about whether guls have different heights in different rows on the same juval.

But the question here is not whether the guls vary in height, but whether the

varying gul dimensions represent perspective. You seem pretty convinced that

this is the case. The hypothesis that it represents dimensionality is subject to

a very simple test. If it does, then the guls in a random sample of juvals

should decrease in height as we go from the ones nearest the elem to those

furthest from the elem. That is, the second rows should be statistically

significantly shorter than the lowest; the upper rows should be statistically

significantly shortest of all. Your second hypothesis is that this is more

common in older specimens, younger ones having guls of more nearly uniform

size.

Testing both of these would take a little labor, but the

methodology is simple. Books, magazines, auction catalogs with a number of

photos of Turkmen juvals are all anyone needs in order to gather the data. For

simplicity, it could be assumed that the published age attributions are

accurate. This would be far more rigorous than anecdotal evidence. Why not

examine the foundation on which your hypotheses rest? You can test it in the

comfort of your library.

Jim Allen's article proposing that early Turkmen

weaving included perspective (HALI, Number 55, p. 98) differs from the one you

base on observations of your juvals. He noted that the upper and lower ends of

minor guls were of different width in old Turkmen juvals, which he interpreted

as meaning that they should be seen as "tilted", rather than as objects lying

flat on the field.

Regards

Steve Price

Posted by Tim Adam on 04-10-2005 11:24 PM:

Hi Steve,

I think no one is saying that Dave's proposals and the

discussion it caused isn't useful. I get regularly shot down when I present my

own research. If I'd take that criticism on my work personally, I'd long have

ended in depression.

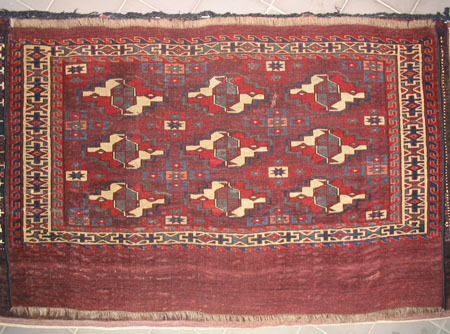

Back to symmetry. For my chuval

the gul hights (in cm) are as

follows:

8.7 8.9 9

8.0 8.3 8.3

8.0 8.3 8

What can I conclude

from that?

In terms of age, the chuval was described as early 19th

century. That seems believable to me. Would you have a different

opinion?

Regards,

Tim

Posted by Steve Price on 04-10-2005 11:49 PM:

Hi Tim

I may be misunderstanding what John Lewis has in mind, but my

interpretation of his repeated calls for Dave to defend his hypothesis sound

pretty negative to my ears. Like you, I'm very much accustomed to the notion of

hypotheses being straw men that can promote the formation of alternatives as

they are proven incorrect rather than as fortresses to be defended from critics.

It's a rare hypothesis that remains intact for very long.

Your

chuval:

1. Early 19th century is plausible, although my opinion (expressed

often around here) is that there really is no way to make reliable age

attributions going back much before about 1900. I guess what that means is that

early 19th century is plausible to me, so is mid-19th century. Either way, I

think it's really a good looking piece.

2. What can you conclude from the

heights of the guls on one chuval? I guess it would be safe to conclude that

guls can differ in height on the same chuval. Not exactly groundshaking news,

though, is it?

Regards

Steve Price

Posted by John Lewis on 04-11-2005 05:56 AM:

Hi,

I thought David’s hypothesis was very weak, but then Steve

modified it without David’s consent – hence my insistence that it should be

David who should defend it. That is not being negative, that is being polite –

indeed I think you owe David an apology.

There is nothing wrong with

putting forward a hypothesis, but there should be some intellectual rigour, some

evidence to support it, either that or it should be phrased differently i.e.

let’s see if we can find evidence for…..

Dimensionality is for Jim Allen

to take forward, my comment was concerned with the pieces in my collection.

These clearly exhibit the difference in height of guls in different rows (3cm in

some cases) and the observation that this makes them “wave in the wind” when

viewed whilst stoned is purely that, an observation.

regards

Posted by Steve Price on 04-11-2005 08:01 AM:

Hi John

I don't know why you think my tossing out a half-baked notion

as an alternative to Dave's original one should require Dave's consent or why

you think you have the authority to insist that Dave defend his.

1. Anyone,

including me, is welcome to toss out things that occur to him as freely as he

would in a street conversation. This is not parliament, and Dave's hypothesis

was not a motion to be considered and voted upon. If it was, his permission

would be needed if someone wants to amend it.

2. Dave is free to attempt to

defend his position, to leave it right where it is, or even to leave town for

awhile and be out of contact with this forum. Neither you, I, nor anyone else

has the authority to tell him that he must defend it. The repeated expressions

of impatience with the fact that he hasn't done in response to you imply an

authority relationship between you and him similar to the one I have with my

kid. I doubt that Dave sees you as an authority figure in his personal chain of

command, and I am aware of no reason why he should.

Dimensionality, as

proposed by Jim Allen in HALI, was an attempt to explain his observation about

the properties of minor guls in very old chuvals. Dimensionality, as introduced

here by you, is based on varying sizes of guls that you observe in your personal

collection. The two are related only by the word "dimensionality" - they are not

attempts to explain the same thing. If you prefer not to apply anything more

rigorous to explain your observation than that they "wave in the wind" when you

are intoxicated, that's your privilege. I cannot help noticing that this is a

very different standard than the one you apply to others, but that, too, is your

privilege.

Regards

Steve Price

Posted by Tim Adam on 04-11-2005 09:04 AM:

Hi guys! Stay cool.

John: What do you think of the gul ratios of my chuval? Can anything be

inferred from that?

Steve: I partially agree with you. I think late 19th

century pieces are not that difficult to distinguish from earlier pieces. But

the distinction beween early and mid 19th century pieces is more difficult.

Often I think people simply equate quality with age - the better a piece, the

older. Even if this is wrong, I find it quite useful, because it quantifies how

people evaluate the quality of a particular piece.

Tim

Posted by John Lewis on 04-11-2005 05:47 PM:

Hi Tim,

I think yours is a nice piece and certainly in the first half

of the 19th century. By itself, nothing can be deduced from the gul heights but

if gul heights were measured over a lot of pieces then I am fairly sure there

would be a statistically significant correlation demonstrating the

“dimensionality” proposed by Jim Allen. Whether dimensionality increases over

time i.e. earlier pieces have more dimensionality is moot. I have seen the

dimensionality effect on 50+ pieces.

Beauty is in the eye of the beholder

– but in Turkmen work, I generally find the earlier pieces more

pleasing

Steve – You accuse me of being “pretty negative”. I am content

to wait for David to present his case; I am not “insisting” that he does, merely

pointing out that it is not polite for the moderator to modify his hypothesis.

Posted by Vincent Keers on 04-11-2005 07:44 PM:

Hi,

The different heights in the guls are caused between the tension

in warps and the straight (if natural depression is the case) wefts, the more

the knotting process comes to and end.

At the beginning (at the bottom) all

warps are free and can go up and down easy. In the end all the straight wefts

have eaten warplength (pushing the warps a bit out of position). Most chuvals

are made on a horizontal loom. So the warplenght is fixed. Now, most think that

in the end the wefts can be beaten down harder so the patterns will compress.

This isn't the case. If the warps are stressed/tight (because of the fixed

length), the warps will push up the wefts so the pattern will

elongate.

Nothing can be done if the chuval is made under poor, nomadic

conditions.

If the chuval is made on a rollerbeem with looped, continuous

warps, so the same chuval can be made 4 or 6 times, it's another

story.

Best regards,

Vincent

PS. Elena says in a book: Palace

gelim = Big carpet.

Palace/Palas isn't Turkmen.

So it must be English. In

a Palace you need big carpets. The British Empire had it's years in

Afghanistan.

Posted by Jerry Silverman on 04-11-2005 07:50 PM:

To any and all,

Are there ANY Turkmen chuvals with more than one gul

that DON'T have differences in the dimensions of those guls - from column to

column and/or from row to row?

Please feel free to submit examples. And

explanations.

Cordially,

-Jerry-

Posted by David R.E. Hunt on 04-12-2005 12:05 AM:

Here's The Ammo, Now Shoot Me...

Greetings All

Sorry to have been absent so long, had quite the weekend

and am still recovering. So busy.

First, thanks Steve for coming to my

defense in my absence Will get

to John's characterization of my photo essay in a moment, but for now would like

to comment on a post by Louis.

Will get

to John's characterization of my photo essay in a moment, but for now would like

to comment on a post by Louis.

Louis states

'The use of palas is

an everyday use on the yurt ground. This fact can easily explain that those

items are periodically replaced and that there are no antique examples

left.'

Is this a perfect example of what I think constitutes the type of

evidence, if properly documented ,that we need to assemble when attempting to

better understand the palas. But the key term here is documented, as this is the

type of verified evidence we need in order to determine, given that we will

eventually be able to, the answer to this riddle which states "Is the palas a

modern convention, or does it possess a history which could qualify it as

primordial of age/symmetry and hence a pile weave Archtype or Prototype?" Given

that little published material regarding this palas is out there,we will have to

scrape together what meager evidence is available, in the form of personal

observations, and be satisfied for now with the conclusions this will allow us

to draw.

John, you have made some eleven postings to this thread, and

during this entire period you have not produced one piece of documented evidence

as of above, and simultaneously entertain a serious discussion of the subject of

my photo essay? I find that ludicrous, especially in light the subject matter of

your commentary. I don't understand your emotional investment.

I thought

the photo essay, more literature than science, clearly an invitation to an open

discussion of the subject matter, yet given the venue in which it is posted ,I

am not surprised that some have taken a more literal interpretation. We would do

well to return to the task of submitting evidence for OUR assertions and

observations, hopefully resulting in a better understanding of the subject at

hand, this Turkmen palas.

Dave

Posted by Tim Adam on 04-12-2005 02:15 AM:

Hi guys!

I sincerely hope this won't develop into a food fight. Let's

get back to the issues.

As far as I can tell there are two main

issues.

1. Since when has the palas been around?

2. Can we find

evidence of design transfer from palas to other weavings?

Unfortunately,

we are lacking direct evidence of really old palas. However, given that many

Turkmen designs can be traced back to Turkish origins, and flatweaves are very

common in Turkey, I find it highly implausible to assume that palas simply

dropped out of the sky sometime in the 19th century. It's already more likely

that palas were pieces of everyday use, and not much treasured. Therefore not

preserved.

To get some indirect evidence on whether palas existed in much

earlier times, I find Marla Mallett's hypothesis on design transfer quite

useful, and I don't understand why this is not discussed here in more depth. If

I understand Marla correctly, we would need to identify specific

technique-related designs of the palas, and then locate old pieces that could

have plausibly copied from palas designs. This would provide some indication

that palas have been around at the time the older piece was made.

And

guys, if you think this is stupid, just say so. I won't take it personal.

I will just

Regards,

Tim

Posted by David R.E. Hunt on 04-12-2005 08:25 AM:

Hi Tim

Yes, back to the issue at hand.

In the first instance, I

have seen an old palas in the trade, which was described as being really old and

hence very rare. It was large, tightly woven,and had subtle color variations of

blue and green. It was quite impressive, and there seemed little doubt that it

was old. The dealer, broken english and all, also had on his walls one of the

best persian tribal rugs I have ever seen in the retail market, so I was

inclined to find him credible

Now Tim, you state

To get some

indirect evidence on whether palas existed in much earlier times, I find Marla

Mallett's hypothesis on design transfer quite useful, and I don't understand why

this is not discussed here in more depth. If I understand Marla correctly, we

would need to identify specific technique-related designs of the palas, and then

locate old pieces that could have plausibly copied from palas designs. This

would provide some indication that palas have been around at the time the older

piece was made.

There also exists a kindered weaving of Turkish Yoruk

origin, which are reputed to be of some age, as discussed on the"Hatch" Gul= Kochak thread. How are these related? This

subject in itself could constitute a whole salon.

This subject has been

breached in a seperate thread titled Archtype=Prototype, which was started in

order to stimulate just such a discussion. Marla Mallett's essay is self

explanatory, and I for one don't know enough about weave structure to further

develop it's application to our subject. Besides, you would need study specimens

to dissect, ect.

No Tim, this is a good idea. In general it is a good idea to assemble

your data before you analize it and draw your conclusion

In general it is a good idea to assemble

your data before you analize it and draw your conclusion A principle which seems to evade some

people

A principle which seems to evade some

people

Dave

Posted by Tim Adam on 04-12-2005 09:49 AM:

Hi Dave,

The problem with the Yoruk weaving in the hatch gul thread is

that it is also a brocade. So, we can't reasonably infer that it has been copied

from a palas. Worse even, the existence of the Yoruk piece draws the whole idea

into question. Suppose we did find a Turkmen pile weaving with a palas design.

It could simply be a copy of the Yoruk brocade rather than of a Turkmen palas.

So, we are back at square one.

Nevertheless, I think it might be

revealing to locate Turkmen pile pieces with evidence of flatweave

designs.

Regards,

Tim

Posted by Filiberto Boncompagni on 04-12-2005 10:32 AM:

Hi Dave.

Perhaps I’m following this discussion rather distractedly,

and getting a bit lost.

Do you mind if I resume it a little?

If Steve

is correct, your points are:

1. The designs on Turkmen palas are

technique-generated (in the sense that Marla Mallett means, for

example).

2. The designs on Turkmen palas are the ancestors of some

motifs on Turkmen pile weavings.

I agree with point #1.

By the way,

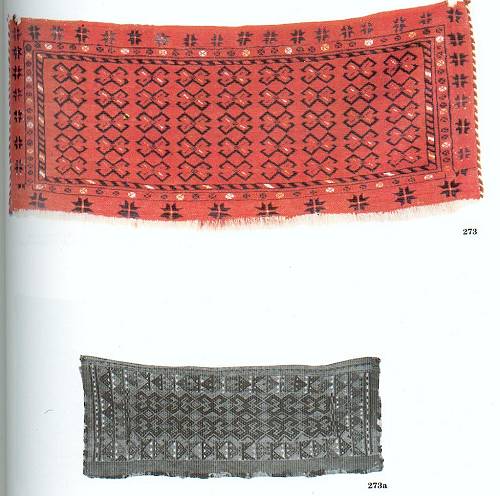

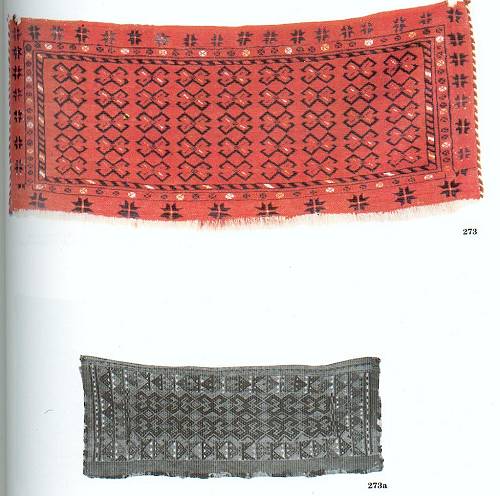

you are not the first. See Jourdan’s “Turkoman”, plates 273 and

273a:

The author compares these two torbas of the Ersari group and

suggests that the motif in the piled one is derived by the flat-woven specimen

(273a). Unfortunately the age of 273a is not specified, while 273 is said to be

last quarter of 19th C.

I disagree with point #2 because I’m convinced

that the “palas” format is of relatively recent and “settled” production:

not only the “palas” are not mentioned in early documentation (see what Louis

wrote in the first page of this thread) and do not have a specific Turkoman

name…

BUT they are also too huge to be woven on nomadic

looms!

“Palas” are probably city products inspired from smaller

flatweaves, like 273a and other bags already presented in the

discussions.

Regards,

Filiberto

Posted by Filiberto Boncompagni on 04-12-2005 10:42 AM:

Hi Dave,

OK, I made a mess (I told you I was following distractly).

2. The

designs on Turkmen palas are the ancestors of some motifs on Turkmen pile

weavings.

I agree on this too. It’s the “palas” format that is

recent, not the design.

Regards,

Filiberto

Posted by Steve Price on 04-12-2005 11:09 AM:

Hi Filiberto

Dave prepared this Salon in order to generate discussion

of his observation that there is a remarkable relationship between palas designs

and some motifs on Turkmen pile pieces. He offered a possible explanation - that

the palas designs were the ancestors of those motifs, the designs themselves

having arisen through technique-driven forces.

Whether this explanation

is correct or incorrect, the observation remains. Unless the relationship is

coincidence, which I think is extremely unlikely, there is some historical

explanation.

Louis Dubreuil and I both mentioned an alternative to Dave's

(I think Louis said it first, but am too lazy to check, so let's assign credit

to him if it flies, blame to me if it sinks) - that the palas designs and the

related motifs on pile pieces descend from a common ancestral pool. This would

account for their relationship, and at the same time accommodates Marla

Mallett's "structure sometimes leads to design" line of thinking.

How do

you (and anyone else) see this suggestion?

Regards

Steve

Price

Posted by Filiberto Boncompagni on 04-12-2005 11:57 AM:

Hi Steve,

I always thought that Marla’s theory on “design following

structure” is faultless.

Also Louis sounds correct: In this type of

work there is no place and no reason for improvisation : they are not made for

pleasure but just for necessity. This is why we find in utilitary items more

archaic features than in dowry items. And why those designs are shared by

severals peoples (with a old common origin) spread over a large territory

(anatolia, turkestan).

So, even if there aren’t ancient surviving

Turkoman flatweaves, it all seems reasonable enough.

Pity there is no

actual evidence. Without it, the discussion remains purely

academic.

Regards,

Filiberto

Posted by Steve Price on 04-12-2005 12:32 PM:

Hi Filiberto

One of the useful things that happens from time to time

on open forums like this is that people find and report evidence from unexpected

sources once an issue is brought to their attention. Illustrations in very old

manuscripts and drawings, cave paintings, accounts of travelers, etc., often

include relevant things that some readers know about and bring to the

table.

Regards

Steve Price

Posted by David R.E. Hunt on 04-14-2005 10:32 PM:

Kalter on Culture

Hello All

Sorry to have been away folks. Just a few quick

comments.

Tim, while I of course don't understand the exact relationship,

it seems to me that these Yoruk and palas could have a common origin. I would

think that their both being of brocade would indicate a greater degree of

relation, and not lesser. They are quite similar, but I don't know, I have not

done a comparison myself. Something to look into.

Steve said,

"the

palas designs and the related motifs on pile pieces descend from a common

ancestral pool. This would account for their relationship, and at the same time

accommodates Marla Mallett's "structure sometimes leads to design" line of

thinking."

I didn't say it better myself

Filiberto, words do confuse us

some times. I wouldn't doubt that the palas format, or even this particular

breed of weaving technique, could be the provenance of settled people. The

Turkmen could (did?) have adopted this technique from their setteled neighbors.

This might explain the mongol origin of this technique, as suggested by the

photo of the madrassa of Ulug Beg in my salon

Find below some quotes from

Johannes Kalter's " Arts and Crafts of Turkestan".

Culturally- with

regard to the development of architecture,poetry, the arts of the book and

painting, and also for the so-called decorative arts- the importance of the

Timurid period cannot be overestimated. Forms and ornaments which appeared in

their characteristic shape for the first time in the Timurid period have

dominated the traditions of the arts and crafts untill well into our

century.(Kalter, pg.39)

Due to the political decay of Turkestan and it's

shift from the centre of a huge world empire in the 14th century to an isolated

peripheral situation, late medieval cultural traditions survived untill our own

time. This makes the study of the recent cultures of Turkestan so fertil, but at

the same time so difficult; they can only be understood from a historical point

of view.(Kalter, pg.41)

Items which can be proved to be older than 100 to

150 years are extremely rare.(Kalter,pg.26)

The cultivation of cotton,

which had origionally been imported from India,had a centuries old tradition,

too. Cotton growing and sericulture (silkworms) were the foundation on which the

flourishing textile workshops in the towns of Turkestan depended. Cotton has

been an important export article since before the Russian conquest. As early as

1880, the long-fibered American cotton-plant was introduced by the Russians and

areas of cotton cultivation were considerably enlarged. A great number of

irrigation projects, particularlly those carried out after 1920, aimed at the

extension of cotton growing. Today, two thirds of the Soviet Union's cotton

harvest is gathered in the Republic of Uzbekistan. Cotton growing in Turkestan

made possible the rise of Russian textile manufacture. As early as the last

decades of the 19th century, cheap Russian cotton printed fabrics were beginning

to supplant the products of the traditional Turkestan textile workshops more and

more, bringing them almost to a standstill, except for the production of ikat

materials with very simple decoration. (Kalter, pg.16)

Dave

Posted by Unregistered on 04-23-2005 02:07 PM:

Isn't anyone going to ask John Lewis to post an image of a 2nd quarter 18th

century yomud chuval?

Posted by Steve Price on 04-23-2005 02:19 PM:

Hi

I think you just did.

Would you be good enough to send me

your name so I can add it to your message?

Thanks,

Steve

Price

A principle which seems to evade some

people

A principle which seems to evade some

people