by Steve Price

When someone mentions the words, Turkmen textiles, we immediately think of the pile weavings for which the Turkmen are so well known. Despite the many Salons and discussions about Turkmen textiles on this site, I don't recall any that focus on their remarkable embroidered textiles except for one brief discussion of Turkmen embroidered hats. This month, I would like to draw attention to them for their aesthetic qualities as well as for the interesting questions that they raise about designs and motifs used on Turkmen products.

The uses of Turkmen flatweaves and pile weaving are very different than those of their embroideries. The woven objects include rugs, bags of various sizes and proportions, trappings for animals and tents. The embroideries, for the most part, are used only as articles of clothing and containers for special objects. Except for asmalyks, trappings for camels in wedding processions, there is almost no overlap in the uses to which pile weaving and embroidered objects are put by the Turkmen. This is not too surprising. The dichotomy seems mostly to be related to the wear and tear an object is likely to have to endure. Turkmen pile weaves are pretty rugged, embroideries are delicate.

There are some other differences as well. The iconography of Turkmen weavings is not usually rich in easily recognized objects like humans, animals, flowers, trees, etc.. The motifs are, for the most part, probably not representational. If they are representational, they are usually so highly stylized as to make identifying the objects they depict a matter of guesswork. I should point out that my opinion on this matter is not universal. There are Turkmen collectors who believe that there are identifiable elephants, birds, sailboats, weapons, horses, and other natural and man made objects within Turkmen pile textiles, especially in the negative spaces. The motifs in many Turkmen embroideries are usually rather easily recognized, and, for the most part, are floral.

With this as preamble, let's look at some examples.

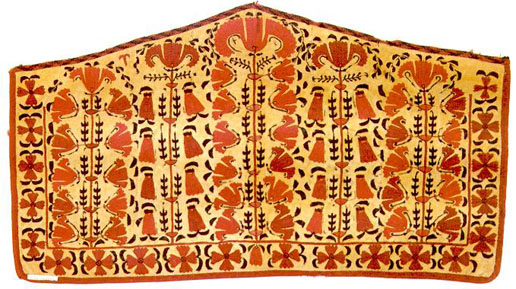

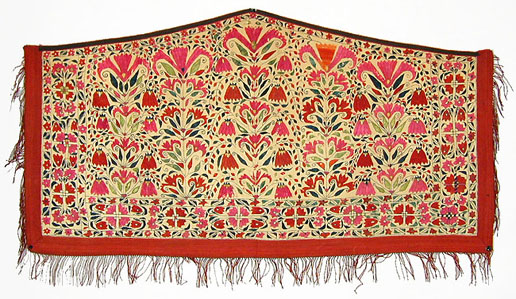

Let's start with embroidered asmalyks. I think these are among the most interesting of the Turkmen embroidered textiles because they have a counterpart in the world of Turkmen pile weavings. Unlike Turkmen pile asmalyks, which (with a few exceptions) do not include realistic elements as motifs, the embroidered examples are decorated with very obvious, even realistic, flowers. Here are a three examples, attributed to the Tekke. They present very different approaches to what is basically the same representational motif vocabulary.

A third major category of Turkmen embroidery is the chyrpy. This is a mantle, approximately in the form of a coat with nonfunctional sleeves, worn by women on special occasions. They were made in several background colors - black, red, green, white and yellow. It is generally believed that the colors signal the age and/or marital status of the wearer, although I don't know how firm the evidence for this is. They are embroidered in silk on silk backgrounds, and although the general style of embroidery is similar on different specimens, the density of embroidery varies widely. Here are some examples.

The extensions on the false sleeves and the "bridge" that connects them are not original, and have obvious synthetic dyes.

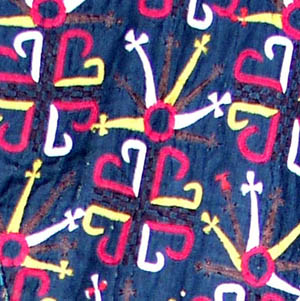

Finally, here is a silk-on-silk embroidered koran bag for which I have special affection.

It is among the few pieces that I acquired in the Covered Bazaar in Istanbul, and, most remarkable for that venue, the price was very reasonable. I think it is beautiful, and I especially like the little triangular embroidered piece that is concealed except when the bag is open. But it also gives me pleasure for a reason that is out of the usual range. Bear with me for a moment. Saul Barodofsky is a dear friend, and has been for some years. He is a dealer, as many of your know, but is also a collector. His practice as a collector is not to engage in commerce on the genres that he collects. One of those is koran bags. He has a collection that was exhibited at ICOC in Philadelphia, so some of you have seen part of it. Over the years, he has steadfastly refused to sell me any koran bag. So, when I bought this one, I brought it straight to his shop to show him one that I owned and that he could not buy from me.

Well, we've had a chance to look at some Turkmen embroidery. They're beautiful, of course, but they also raise some questions that I find interesting. Here are some to help us get started.

1. On what basis can we make tribal attributions of Turkmen embroideries? Palette is sometimes helpful, but not always. The ground cloth on which they are embroidered, for instance, was probably almost never woven or dyed by the Turkmen themselves, and their colors may have simply been whatever the opportunity of the moment offered. Yet, the marketplace attributions seem very confident.

2. What significance, if any, does the varying density of embroidery carry in Turkmen work? In pile weavings, we generally associate uncluttered, spacious fields with greater age. Is this likely to also hold true for embroidery? On what is this opinion based?

3. Why are motifs so seldom representational on pile weaves and so often representional on embroideries? Is it because embroidery patterns and designs can be drawn on the background fabric in advance? Were there special artisans who did this phase of the production of embroideries, as there were in the Uzbek urban centers that produced suzani?