The Salon du Tapis d'Orient is a moderated discussion group in the manner of the 19th century salon devoted to oriental rugs and textiles and all aspects of their appreciation. Please include your full name and e-mail address in your posting.

Streams of Influence: Motives and Origins of Moroccan Carpet Design

by David R.E. Hunt

Moroccan carpets are somewhat unappreciated and perhaps misunderstood by many rug collectors, due to any number of factors, such as the ubiquity of blatant synthetic dyes, seeming rote and monotonous repetitive banded patterns, and misinterpretation of a weave which may seem loose and shabby in comparison to more traditional Middle Eastern work.

It does seem that a great percentage of Moroccan carpets are of the coarse weave and lurid dye variety, a quality which could be ascribed to Morocco's close proximity to the west, with its availability of inexpensive artificial dyes and perhaps even more importantly its being a major tourist destination with a virtual tidal wave of airport art quality weaving generated in pursuit of the souvenir trade.

But there are interesting, strikingly beautiful, authentic, and valuable weavings to be found among the everyday - and of course not everyday - yet just as with their Middle Eastern counterparts, it is a familiarity with designs, materials, techniques,and formats that allow one to distinguish the average from interesting and exemplary.

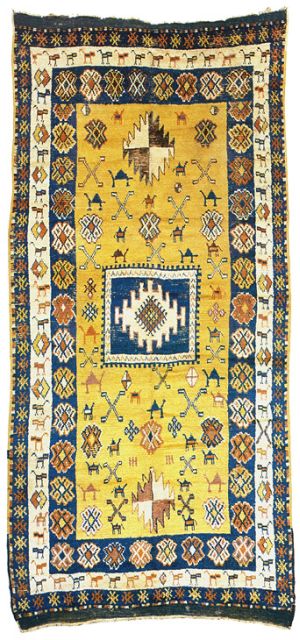

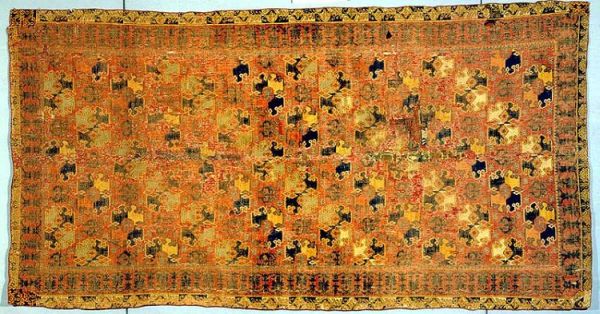

For example, this is a Moroccan rug from the Spring 2002 Rippon Boswell & Co. catalogue with an estimate of 12,500 Euros. Alan Marcuson, reviewing it on Cloudband, wrote: "I have to declare an interest here. I bought this rug in the early 90's; it cost $350 and paid for a lovely holiday. To this day it is still one of the oldest and most beautiful piled Moroccan rugs I know and it would be difficult to find another with such a good design, colors, and real age. There are very few Moroccan carpets which can be dated to the middle of the 19th century; I consider this to be one of the best Moroccan village rugs around."

I have seen numerous examples of this design in the High Atlas mountains, most with obviously synthetic dyes with faded tips. But there are a lot of carpets to sort through in this area, and you can spend numerous afternoons sifting through piles of weavings in search of that special piece. An advantage to buying in these more remote regions, aside from the obvious proximity to the actual production areas and hence a bounty of rural weaves, is the absence of those extortive high pressure sales tactics so prevalent in tourist areas.

This is not to say that museum quality Moroccan rugs lie around every corner. But good rugs are to be found, and those willing to spend the time and energy required to familiarize themselves with these Moroccans might be suprised at what they do find.

The purpose of this salon is not to aid in the identification of museum quality weaving, which would require a level of expertise beyond mine, but an attempt to introducethe weavings and people of Morocco or the Maghrib, as these people refer to this geographic region, and to visually explore some potential origins of the motives, designs and traditions represented in Moroccan rugs and Morocco.

As will be apparent, my life has become inextricably bound to Morocco, and this discussion represents an attempt to clairify my thoughts and organize this information into a coherent body. While I have some access to first hand and personal knowledge of this region, I am neither anthropologist nor historian, so this discourse will be general rather than technical, of impression and inquiry.

I will begin with a brief overview of the history of Morocco, with an emphasis placed upon the Muslim conversion and the introduction of Arabic culture. Next, a look at some examples of what appear to be Turkic influences in Morocco, followed by a brief survey of some of those Berber peoples who seem to have influenced the arts and architecture of the Maghrib.

The Arabs and Islam

The introduction of Islam and Arab culture figure prominently in the history of Morocco and continues to do so even now; we would be remiss to fail to address this most instrumental component of the history of the Maghreb and in turn most all the weaving cultures of the orient.

To better understand Islam is to understand its chief proponent, the Prophet Mohammed. Many of the customs and rituals of Islam are undoubtably those which the prophet, as an Arab Bedouin, practiced and were institutionalized by Islamic civilization. But of course truth is hardly ever so simple. All the peoples of this region of the world have had their cultures shaped by similar environmental challenges and a similar ecology, and as such some duplication is to be expected.

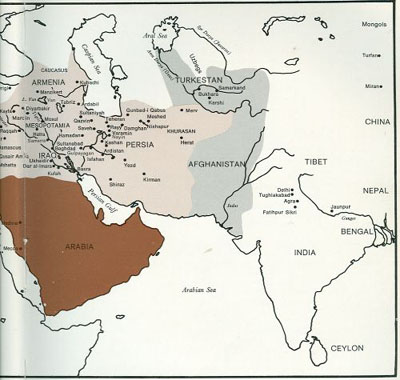

For the Maghrib, Arabic influence is fairly straightforward. Neither the Turkic nor the Mongol invasions reached the Maghrib, their conquests extending only as far as Algeria. This could prove to be of some consequenc to the design pool of Moroccan carpets. It follows that design influences found in Moroccan weaving are of trade, immigration, or emulation and not of conquest. The cultural streams of influence are perhaps less muddled than in other Islamic regions.

But most important, and perhaps more so here than the other regions of the Islamic world, it should be remembered that the spread of Islam represented much more of a religious enlightenment than a conquest. One of the most salient features of the spread of Islam lies in the fact that it was more a reaction to the chaotic and despotic character of pre-Islamic societies and, in turn, was a rebellion against the existing order rather than an Arabic conquest.

The Muslims were capable and moral leaders, they represented order and civility, and especially a degree of hierism which people found an appealing alternative to the prevailing orders. The Muslim conquest was more a matter of indigenous peoples rising up against despotic leaders under the tutelage of Muslim (Arab) leaders than an Arabic invasion.

The pre-Islamic civilizations of Morocco were usurped by Berber Muslims from Syria and Algeria, and not so much by Arab Muslims directly, yet the Berber conquerors brought the Arabic language, customs,and in turn civilization, from Arabia.

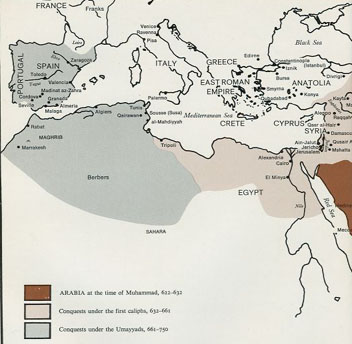

This map from the book, The Art of Islam, depicts the

spread of Islam and Arabic culture between the years of 622-750 AD.

We know that they brought their language and religion to these regions, but

what

of other customs?

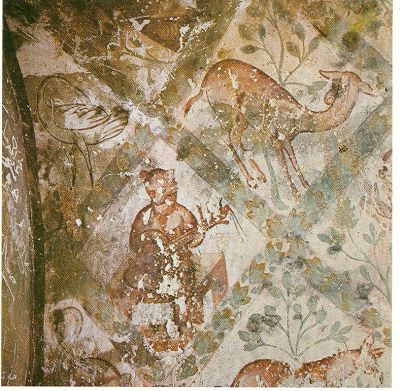

This detail of a fresco from the Qusair Amra in Jordan is reminescent of lattice and compartment designs found in carpets. And is that a fox seated on a chair playing a musical instrument?

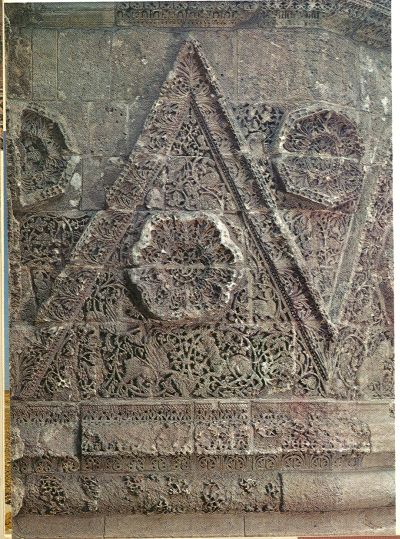

The Qusair Amra was built during the Umayyad period, as was this Mashatta palace (743-744 AD), whose limestone facade seems to have been executed in a style believed to be of Medditeranian origin and consisting of a zigzag frieze of upright and inverted triangles containing rosettes and acanthus leaves. This palace is unique in that it exhibits characterists of Roman, Sassanian, Byzantine and Mesopotamian architecture.

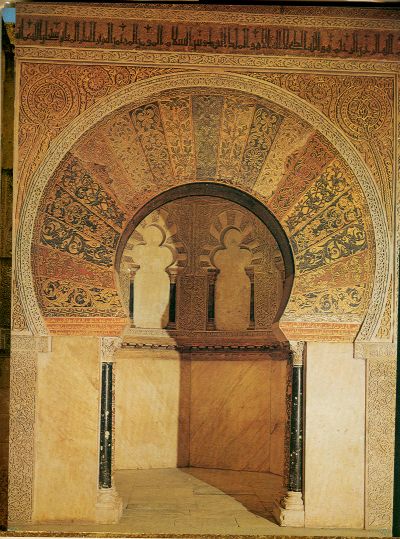

The greatest of the the Umayyad architects, Caliph al-Walid, whose empire extended from Transoxiana to Gibralter, constructed a Great Mosque in Damascus which in its time was a "wonder of the world". Its influence can be seen in the Great Mosque of Aleppo, which is practically a copy, in the mosque of Qasr al-Hair, and in the Great Mosque of Cordova, pictured here. This mosque seems of central importance to the artistic and cultural history of Morocco. The reddish orange color, seemingly derived from the color of henna and hence of much symbolic significance, is a constant in the arts of Morocco, as are the bands of geometric repeats, and, of course, the emphatic mihrab. And don't forget those paired rosettes above the windows on either side of the mihrab.

This Great Mosque of Cordova, the third largest mosque in Islam, begun in 785-786 AD and utilizing Byzantine artists brought in from Constantinople to perform much of the decorative work, is lavishly ornamented with gold and mosaic as in the mihrab pictured here.

Some will remember this rug from an archived post on Turkotek, discussing the Andalusian carpet exhibit at the Textile Musuem in Washington, D.C.. The stylised floral pattern of the outer border reminds of the decor of the mirab above - and they are both from Spain. As Dr. Du Ry states in The Art of Islam, "In the fifteenth century, carpets in the Mudejar style were made in which the surface was divided into diamond shapes, with octagonal 'Turkish' motifs appearing on a blue ground". Could this be a Mudejar carpet?

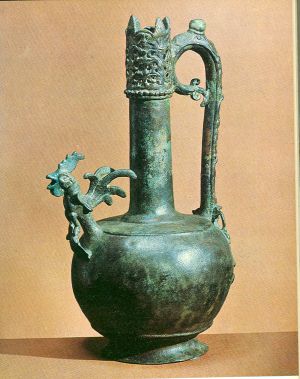

This 16" bronze ewer probably belonged to the last Umayyad Caliph, Marwan II, killed by the Abbasids while fleeing his capital in North Mesopotamia c.750. His death marked the end of the Umayyad period and the beginning of the Abbasid, a movement of the capital from Damascus to Baghdad, and an orientation more Asian than Medditeranian.

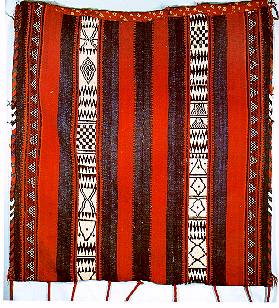

These photos of Arab bedouin weavers and weavings from Saudi Arabia may resemble those produced by Arabs in the past. I think it is safe to say that they suggest the weavings produced in much of the Islamic world today.

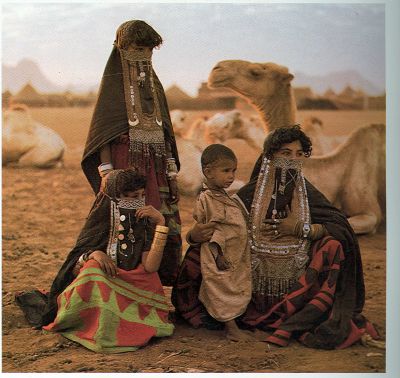

These women are members of the Rashida tribe from the horn of

Africa. Note the elaborate, minutely detailed ornamentation

which adorn the burqua or veil of these Muslim women, the consequence of closer

proximity to the centers of Arab culture.

These photos are of my wife during her employment in Saudi Arabia. She

was retained by the Royal family, hence the luxury

accommodations.