Michael Wendorf’s post in the “resources” thread is very useful. It appeared as I was composing something on how felts are made. The summary Michael provides from the “Nomads of Eurasia” volume contains a great deal of information related to this thread I’m starting here. I have recopied it into this post for convenience. Here is most of it again:

"There were several ways to make patterned felts." The following are excerpts from the discussion that follows:

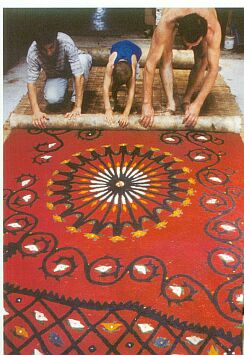

1. The rolled pattern technique known to Turkmen, semi-nomadic Uzbek, Kirghiz, Kazakh and Karakalpak peoples. The Turkmen laid out a pattern of colored wool and added several layers of undyed wool which served as a background. Kazakh and Kirghiz women used thin or lightly rolled colored felt for pattern and laid it on a semi prepared base. In both techniques hot water was poured over the wool mat, and the mat was rolled up into a bolt, which was rolled back and forth on the ground for several hours to compress the wool.

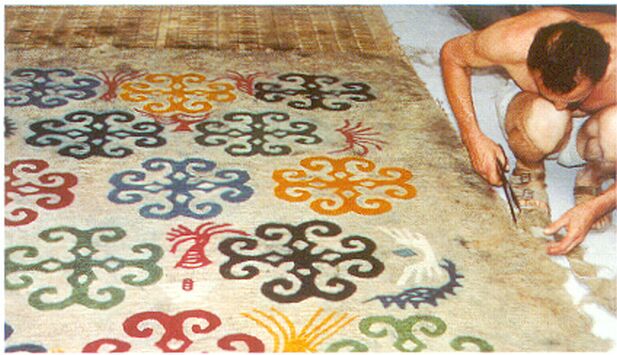

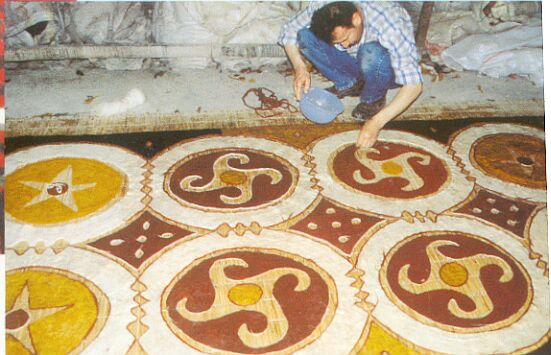

2. Mosaic technique, known only to the Kazakh, Kirghiz and seminomadic Uzbeks. Patterns were cut from two pieces of felt of different colors and the pieces were then sewn together, the piece of one color served as background and the other, the foreground. Colored cord that emphasized the ornamental outlines was sewn on top of the seam joining the background to the foreground. The patterned felt derived from this process was superimposed on a felt piece of coarser wool, and the two pieces were quilted together along the outlines of the design.

3. Techniques of applique, quilting on felt and patterns applied in colored cord. These techniques were used almost exclusively by Kazakhs and Kirghiz.”

As it happens I also have this volume and have scanned some of the photos that Michael mentions and will present them below.

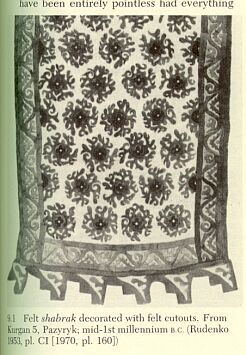

It is interesting to conjecture when the conditions needed for the production of felt first existed. One needs a lot of wool, so the mere presence of sheep would not be sufficient, the first felts likely had to await the development of a more substantial and less “kempy” coat. Barber says that the first well-documented item of felt is from the early Bronze age. She says lots of felts begin to appear about 700 B.C. Here is a felt found at Pazyryk.

(Notice the caption indicates that this is of the “applique” variety mentioned in Michael Wendorf’s post.)

Second, there are instances in nature that could suggest felt to humans. A number of animals cough up hair balls, periodically, which would give evidence of the matting capabilities of wool.

Further, any attempt to wash sheep’s wool (to clean it for example) is likely to result in some “felting” and the conditions under which felting would occur would be readily discovered. One of the first things books on washing sheep’s wool caution against is pouring water on wool when you wash it. To avoid felting one puts the wool in a colander-type pan and immerses it in water. So the most instinctive washing move would produce felt in wool.

Barber also indicates that felts can be “…divided into two types: fiber felts, which are made directly from loose fibers, and woven felts, in which the fibers are spun and woven first and the resulting cloth is then subjected to a felting process.” The “boiled wool” winter caps and gloves that one encounters in mail order catalogs are of this latter type.

I was puzzled initially by Ms. Raissnia’s indication in the initial salon essay that the wool used in felting is “spun.” I think she refers to the wool used to make the designs only. It seems to me that the wool used to make the subsequent layers of felt which is literally “sprinkled” on top of the design lawyer is not spun.

It is also interesting to see that various methods are used to provide the “rolling, rerolling, kneading, beating,” and other ways of subjecting the wools to “friction and pressure” for a number of hours.

Barber says in her “The Mummies of Urumchi” book that “To make a felt as a nomad does, you scatter wool cleaned and fluffed-up all over a mat in an even layer, sprinkle the wool with whey or hot water, roll up the mat with the damp wool in it, an tie the bundle to the back of your horse so as to mash and knead as you ride all day. At night you unroll it, sprinkle it down again, reroll it the other way, tie it to the horse for another day’s punishment. Soon the wool has matted as thoroughly as you please. You can decorate it by placing tufts of colored wool (or bits of colored felt) in a pattern on top of the layer, then mash it some more. The whey and the hot water cause the scales on the surface of the wool fibers to stick up rather than lie down, promoting the tangling that mats the fibers. As such they have the opposite effect from “conditioners” that many women today put on their hair to decrease tangles. Sheep’s wool is virtually the only natural fabric that will tangle so inextricably.”

Notice in this description, the design is applied last, rather than first as Ms. Raissnia’s Persian felter does it.

In addition to tying an incipient felt behind you on a horse and riding for two days to give it the pummeling that produces more finished felt, there are several other methods used.

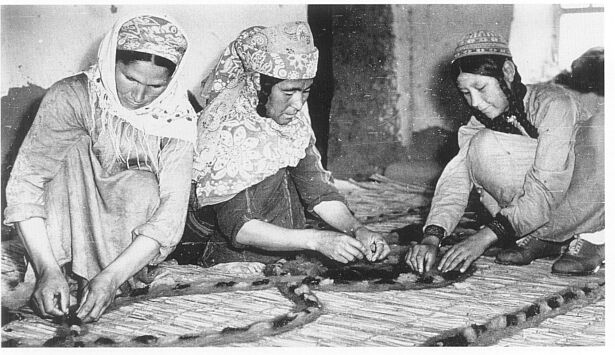

The one with which I was most familiar prior to seeing the video that Ms. Raissnia and her husband have produced, is that used frequently among Turkmen. Here from the “Nomads of Eurasia” volume are two photos of Turkmen women making felt.

The first shows them arranging the patterning layer on a mat (design first, and on bottom, like the Persian felter).

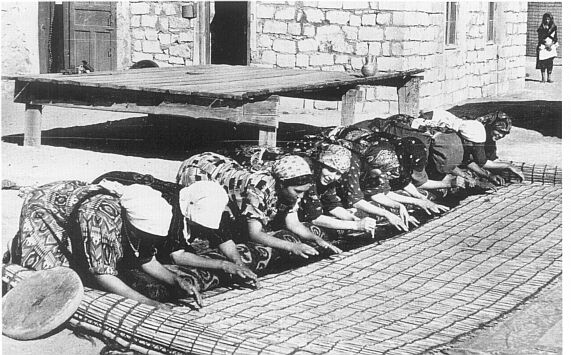

The photo below is of a number of Turkmen women on knees and forearms, kneading and rolling and rerolling a larger felt.

This method is the one that dominated my “picture” of felting before seeing the Persian felter at work in the video tape. A relatively large number of women working side by side in this posture.

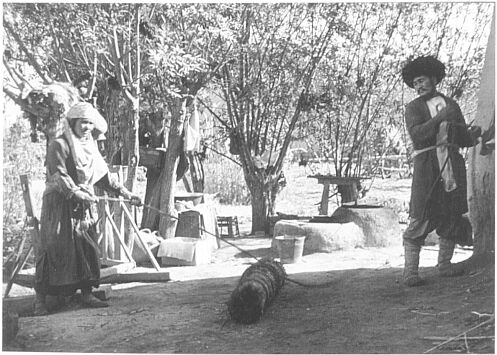

Here is a method that appears to require only two and a rope arrangement.

Apparently this man and woman can roll this piece of felt-in-the-making back and forth between them by pulling on the ropes.

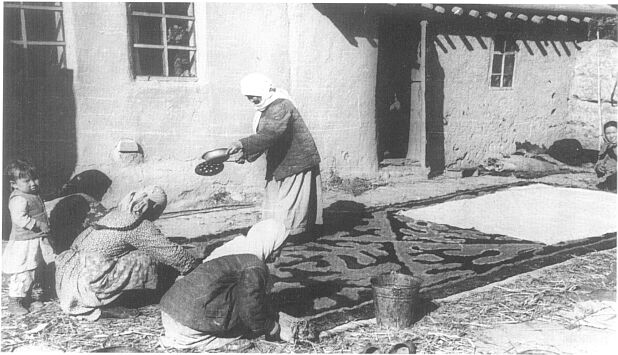

Here, below, is an image of four Kirghiz women making a felt piece. This appears to be of the applique variety.

I have also taken one image of the old felter at work from Ms. Raissnia’s initial salon essay for comparison and comment. I have lightened this image so that you can see the detail in it.

I am unsure of this gentleman’s age, but I’m guessing he’s at least in his 60s. He is in this photo, rolling and pummeling the felt he is making entirely by himself by “dancing” on it in his barefeet. He holds what appears to be a cane for support, but believe me, this man is in good physical shape. He does the rolling, balancing dance supported only slightly by this “cane” for what seems like a very long time in the video. His matter-of-fact skill and physical stamina are remarkable. To see him work alone like this violated seriously my previous pictures of how felting is done.

One further quote from Barber about felt:

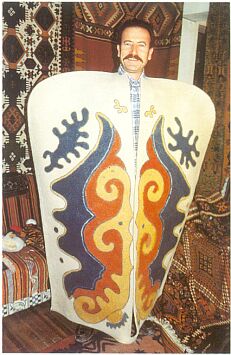

“Nomads use felt not just for its convenience of manufacture. More important, it can be made so dense as to be nearly impervious to wind and water, yet it is far lighter than other waterproof materials like wood and metal. The herders spread great sheets of felt over light frameworks to produce their famous round tents, or yurts…and they use it for flooring (rugs), bedding, luggage, saddle gear, hats, cloaks, and other clothing. They even use it to make dishes for solid foods and padded carrying cases for the china cups used to drink. Along with horse riding, felt made Eurasian nomadic way of life possible.”

Regards,

R. John Howe