Posted by R. John Howe on 10-15-2003 07:35 AM:

Chilkat Distributed Abstraction Evaluated

Dear folks –

The Chilkat practice of using “distributed abstraction”

in their designs is interesting. Steve Price pointed out early that it would

seem to be a rather sophisticated species of abstraction. This made me wonder

what other legitimate evaluative statements might be made about it. Is the

distributed abstraction of the Chilkat’s a demonstrably “good” species of

abstraction, in some sense, or can it be critiqued?

I ran into a web site

that talked about “modeling” and in it, there was a quoted sentence from

Picasso:

“Art is the lie that helps us see the truth.”

This led me

to the notion that perhaps one way to evaluate various sorts of abstraction

might be to ask what purposes do they seem to be aimed at and then to examine

how successful they seem in achieving these purposes.

Samuel

characterized the move to distributed abstraction one primarily motivate to

“fill the space.” But I wonder whether there might not be more to it than this.

(What Chilkat “truths,” for example, might the move to distributed abstraction

seem to reveal or to more effectively accentuate? What advantage might there be

in displaying two mouths in the abstracted design of a creature with only

one?)

What objectives do you think the Chilkat dancing blanket designers

might have had when they moved to distributed abstraction and how successful to

you think they are in achieving them?

What are some other noteworthy

instances of distributed abstraction in the world of art and how do they

compare?

Regards,

R. John Howe

Posted by R. John Howe on 10-15-2003 08:19 PM:

Dear folks -

Come, now. There must be opinions, perhaps even informed

ones, about the Chilkat entry into the field of abstraction in art.

Could

it be that the opening up of the animal might in part be intended to show a

greater proportion, on a flat surface, of a figure that occurs in life in the

round? This seems to me less likely. Parts are repeated in the abstraction, but

it does not seem to work noticeably to let us see some part of the "back" of an

animal that is "facing" us.

Or, to take up a critical question, are the

designs on the Chilkat dancing blankets "intelligible?"

One notion of

"intelligible" might be do they successfully communicate a discernible

something? Maybe not, if they are/were ambiguous, not only to the scholars, but

to the Chilkats.

Another notion of "intelligibility" might be, do/did

they call up a particular human response (to someone in the Chilkat culture)

with some reliability? These designs would clearly succeed in this latter

function if they are of animals in a "crest" relationship with the makers' tribe

or clan, but it would seem that a realistic rendition would accomplish this just

as readily. It is hard to see how the particular species of abstraction the

Chilkats adopted might improve the design's ability to serve such a

function.

There must be a number of similar

questions.

Regards,

R. John Howe

Posted by Sue Zimmerman on 10-16-2003 12:45 AM:

Hi John,

For distributed abstraction and calculus even, the Vedas are

the place to go. I can't sing in Sanskrit via computer though, so I guess, as a

concrete example, that's out. But you know those Arabic numerals in rugs? The

Arabs called them "Al - Arqan -Al - Hindu" which means Indian figures. They

should know, they were the translators. The Indos of the Indo-Europeans were

heirs of someone else too, I guess. So, anyway, the closest I can get to another

example of distributed abstraction in art, without making people faint, is Mayan

hieroglyphics. Sue

Posted by R. John Howe on 10-16-2003 09:21 AM:

Dear folks -

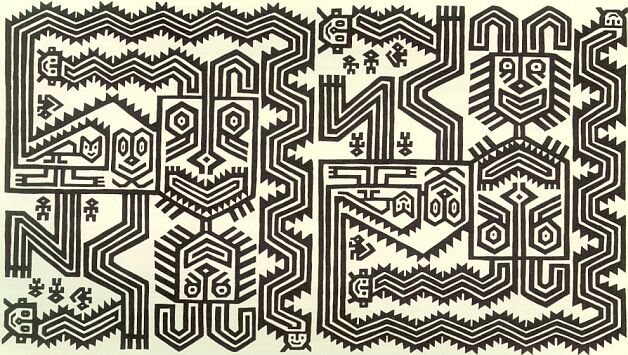

I tried to follow Sue Zimmerman's suggestion that Mayan

hierolyphics might be an analog of the distributed abstractions of the

Chilkats.

The Mayan hierorglyphics are abstracted designs and could be

seen to resemble Chilkat devices.

Looking for some to show you I found,

oddly, that some of the sites the provide the most accessible images are some

that are basically interested in selling you T-shirts.

Nevertheless,

learning can occur in odd places so here are a couple of links to explore.

(Often the hieroglyphics are presented in entire pages that make the devices

seem too small to examine, but usually if you click on the lower right corner of

such a page, a red squarish shape will usually appear. This, when clicked, in

turn produces a larger readable image of the page.)

http://www.halfmoon.org/syllabary.html

Look around a

bit in the sub-links in the site above.

http://www.geocities.com/mayanglyphs/mayan.htm

Although

the Mayan hieroglyphics are clearly abstractions it is not clear to me how they

might be seen as an instance of "distributed" abstraction. Their elements are in

fact those of a written language, something the Chilkats are reputed not to have

had.

So while I admire Sue's imaginative suggestion, the Mayan

hierographic systems seem to me distinctive from the Chilkat

abstractions.

Regards,

R. John Howe

Posted by R. John Howe on 10-16-2003 01:57 PM:

Dear folks -

We could also attempt to evaluate given Chilkat dancing

blanket designs on more familiar aesthetic grounds.

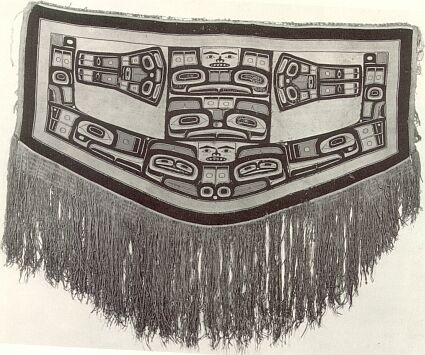

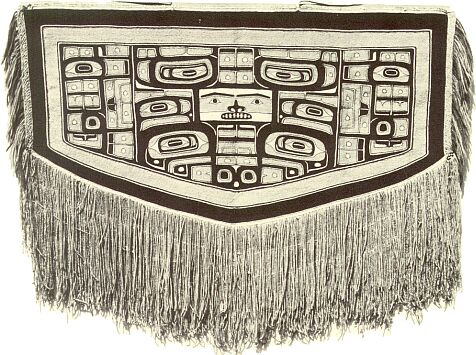

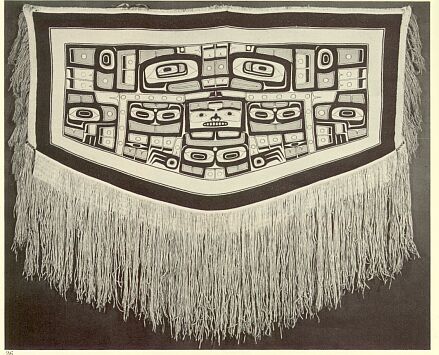

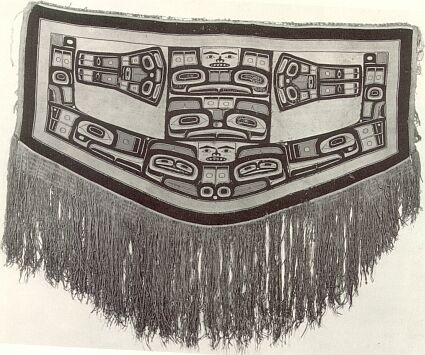

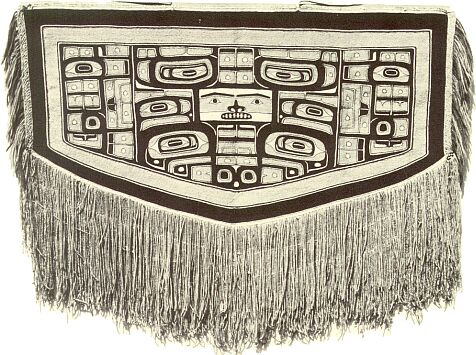

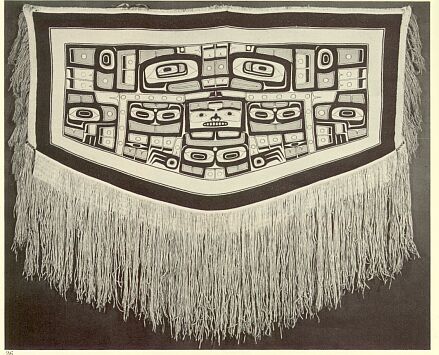

Here are three black

and white images of such blankets:

How would you rank these three

Chilkat blanket designs in aesthetic terms and why?

Regards,

R.

John Howe

Posted by Filiberto Boncompagni on 10-17-2003 04:57 AM:

Hi John,

How would I rank these three Chilkat blanket designs in

aesthetic terms?

Very low.

Why?

Because I don’t like them.

Why?

I don’t know, they simply don’t turn me on.

One of the reasons could be

the relative lack of colors.

So, I tried a little experimental

coloring:

It looks a little better but I still don’t like it.

I

DEFINITELY prefer the Turkmen Asmalyks.

Because I like them. Why? I don’t

know. Perhaps I have to read again Christopher Alexander’s theory on "a set of

tools to judge beauty". But I never found it very

convincing…

Regards,

Filiberto

Posted by R. John Howe on 10-17-2003 05:42 AM:

Hi Filiberto -

Your reaction is very interesting. Chilkat dancing

blankets seem here to command generally very positive reactions from those who

collect in other areas. I'm not sure why that is. Perhaps in part because totem

poles and their designs (which are also of the "formline" variety) are likely a

part of the early education of most U.S. students.

I was in conversation

with a TM board member the other night at a TM reception, marking their current

work with and exhibitions Navajo weavings and some quilts attributed to

African-Amercians. This board member and his wife are long-time collectors of

African art and he has a large collection of Caucasian flatweaves. They also own

several Navajo blankets. When I mentioned the Chilkat dancing blanket, his eyes

lit up and he confessed that they had wanted to own one for some time.

I

think the boldness of their graphics is what many here find appealing. I don't

think it depends much on color, although the colors used do add to their

attractiveness for me.

But I'm very glad that you said out loud that they

do not speak to you.

By the way, you likely know, but your suspicion that

Christopher Alexander's book on aesthetics (using Turkish village rugs as his

focus) would likely not help much, is probably correct. We tried to apply him

with some expert assistance in Salon 11.

http://www.turkotek.com/salon_00011/salon.html

The

results did not encourage us that Mr. Alexander's formalism might be a source of

help. In fact, if he is right, we would all have similar reactions to the

Chilkat dancing blanket, since he holds that our aesthetic evaluations are

essentially "hard-wired."

I am hoping that I can find a few to take on my

comparative task above, despite the fact that it is "buried" in a thread that

not everyone will be encouraged to look at again.

Regards,

R. John

Howe

Posted by Steve Price on 10-17-2003 06:01 AM:

Hi John and Filiberto

I like the Chilkat textiles a lot, although I

agree with Filiberto that the color makes them much more attractive. I'm not

sure that the appeal they have for me is aesthetic - that is, I don't think I'd

describe them as beautiful per se. I find them extremely interesting, and

I find myself looking for all the body parts and how they relate in the pieces.

That is, their appeal is more intellectual than emotional for me.

I don't

know that I've ever seen one at close range, and scale makes a lot of difference

in how something affects me (and probably other people, too). I can tell that

the Salor trapping in Mackie and Thompson's book is clearly very beautiful just

from the picture in the book. But seeing it in the wool at the Textile Museum

(I've seen it twice, now) has taken my breath away each time. Its scale is

extraordinary, and this adds greatly to its impact.

Of the three images

you posted in this thread, I tend to prefer the third. I think it's the

orderliness in the arrangement of the field. I dislike the first one because it

doesn't fit my prejudice of what it should be. I expect a Mercator projection of

an animal; that one looks like a partially disassembled totem pole. For all I

know, someone who collects these things and knows a little about them could

educate me and change my preferences completely, though. My first few rugs were

modern formal workshop Persian carpets, and I thought they were about as good as

such things could get.

Regards,

Steve Price

Posted by R. John Howe on 10-18-2003 05:54 AM:

Dear Steve and all -

Here is a little more information about the three

Chilkat blankets above that might help in our evaluations of them.

The

first is likely the oldest, having been collected by a named person in 1932. It

is said to have a "raven" design.

The second piece was also collected by

a named person, and is estimated to have been woven in 1900. This design is also

seen to be either of a "hawk" or "raven" variety.

No estimated weaving

date is given for the third blanket, but it is of the "paneled distribution"

variety of abstraction that seems to have characterized the most fully

"developed" (I know that word is objectionable) stage of Chilkat design

progression that seems to have its acme sometime in the 19th century. Emmons

describes it as a "diving whale" rendition.

I am also interested in

Steve's suggestion that the appeal that the Chilkat dancing blanket designs have

for him is that they are "interesting" in a way that he feels falls outside the

world of "aesthetics." I cannot, of course, question his experience, but

"interest" would not seem, necessarily, to bar the possibility that the interest

had an aesthetic character. I wonder how he detects that his particular interest

is without an aesthetic dimension.

Regards,

R. John Howe

Posted by Steve Price on 10-18-2003 07:55 AM:

Hi John

Interesting and beautiful are not mutually exclusive. The

first seems to me to be an intellectual response, the second an emotional one.

Most worthwhile things have elements of both, but in varying proportions.

To go back to the TM Salor trapping, for instance, I find it both

extremely interesting and extraordinarily beautiful. The Chilkat blankets don't

hit me as terribly beautiful, but I find them very interesting. That is, I find

myself mentally playing with their content, rearranging elements in my mind,

fitting things together various ways to try to make sense of them. Their appeal

to me is more nearly akin to that of a well written book (Michener's The

Source comes to mind for its remarkable composition) than to that of, say,

Richard Farber's wonderful ballet score, Five and a Half.

Regards,

Steve Price

Posted by R. John Howe on 10-18-2003 08:03 AM:

Hi Steve -

Michener writes well?!?!?! My God!

Regards,

R. John Howe

Posted by Steve Price on 10-18-2003 08:53 AM:

Hi John

He's probably the most widely read 20th century American

author, which makes me suspect that he does something right. But I used the word

"composition" intending it to mean the way the book is structured rather than as

a comment on his command of written English (which I also think is excellent,

that just wasn't what I was talking about).

Regards,

Steve

Price

Posted by R. John Howe on 10-18-2003 02:59 PM:

Hi Steve -

I didn't mean to gasp. I was just momentarily distracted by

an unexpected example.

Michener did sell a lot of books. And he is

reputed to have done a bit of research. A bit formulaic (is that a word?) for my

taste.

Back to the rugs.

Yes, I see your distinction. You can

admire aspects of craft without experiencing much

beauty.

Regards,

R. John Howe

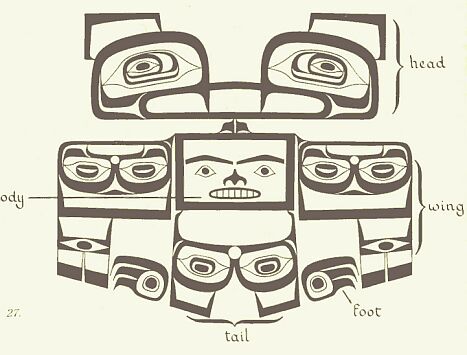

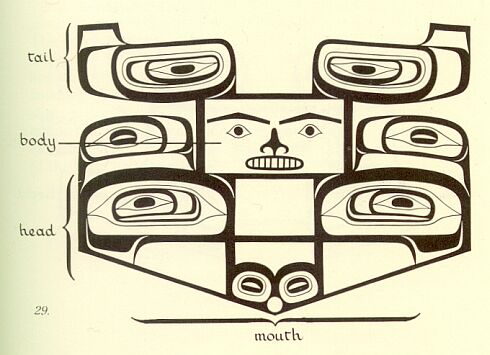

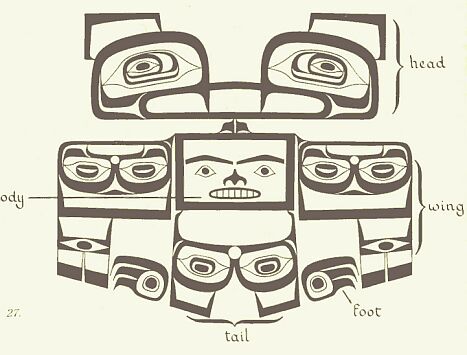

Posted by R. John Howe on 10-19-2003 05:44 AM:

Dear folks -

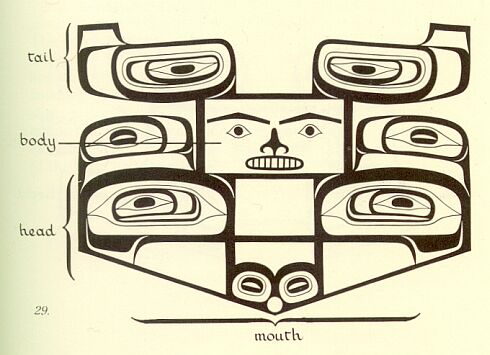

It may help in our evaluation of the designs on Chilkat

dancing blankets to have a couple of concrete maps that indicate which aspect of

a given design represents what.

Here are two examples from Samuel. In

each case I will give you first an overall image of the entire blanket, followed

by a labeled analysis of part of the designs on it.

This design is said by Emmons

to represent a "diving whale." . Here is how the various parts of it are

labeled.

Some of this labeling is not unexpected, but notice that what

we might ordinarily see as a "face" in the center is interpreted as the "body"

of the animal. And the "head" and "mouth" are seen to be represented by the area

of design in the pointed bottom. And there are "tail-like" features in the

designs labled "tail" but there are also things that look very much like "eyes."

We might not be able to guess, without expert assistance, which part of this

design represents what part of the animal or how the animal is oriented in this

abstraction.

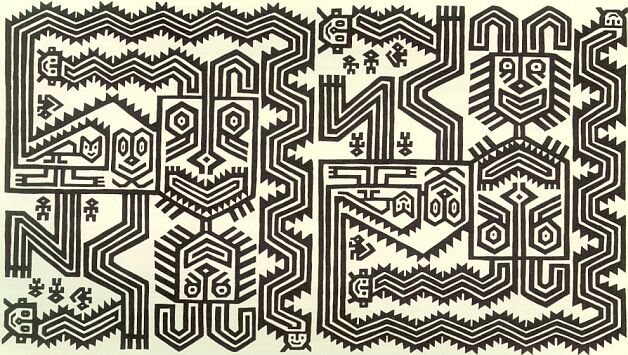

What the second design below represents is in dispute

between two scholars. "Emmons say it represents a "sea bear. Boas calls it a

standing eagle."

Here is a labeled interpretation of it.

The "body" is still what seems

like a "face." but now the "head" is seen to be at the top and the "tail" and

the "feet" at the bottom.

It is not entirely clear to me from Samuel's

treatment whether these labels are those of the scholars alone or whether they

are at least in part shared by the Chilkats themselves.

Perhaps these

labeled interpretations may help us decide about the character and quality of

Chilkat abstraction.

Regards,

R. John Howe

Posted by Steve Price on 10-19-2003 07:48 AM:

Hi John

I am relieved to see that people who write about Chilkat

motifs are just as likely to disagree on interpretation as are people who write

about textiles and about African sculpture and masks. My impression in the

latter two fields is that much of the mischief arises from marketplace hype -

vendors telling the buyers some romantic story that makes a piece more

attractive to the buyer. The fairy tale then just gets embedded by repetition. I

suspect the same is true for American Indian art.

Regards,

Steve

Price

Posted by R. John Howe on 10-19-2003 09:15 AM:

Steve -

There are fables that apparently go with most of the Chilkat

dancing blanket designs. They are usually about how the tribe established a

"crest" relationship with a given animal.

I have spared you from

these.......so far.

But the ones I have encountered seem less likely

market driven than does the average rug story we hear about

nowadays.

Regards,

R. John Howe

Posted by Sue Zimmerman on 10-19-2003 10:19 PM:

I might be a bit more inclined to read books by experts if their labeled

interpretations matched up with what they wished to interpret. None of these

elements in the the drawings match up with those in the photos. For me that's a

hard thing to get by. Sue

Posted by Steve Price on 10-20-2003 05:43 AM:

Hi Sue

I have the same problem with these. For a brief moment I

thought I had solved the puzzle. If you look at the "face" that's labeled "body"

in the first one (the "diving whale"), you can see that the nose could easily be

read as a whale. Sadly, the piece that is interpreted as either a standing eagle

or a bear has the same design element for a "nose".

Regards,

Steve

Price

Posted by Sue Zimmerman on 10-20-2003 11:42 AM:

Hi John and Steve,

The corpus of prehistoric knowledge was mostly

conveyed by song and dance. One of the reasons archaic visually depicted

languages remain virtually undeciphered is that the minute variations within the

individual hieroglyph's "cells", which are visually depicted memory devises,

despite having great significance, have been "deciphered" out of the equation.

What remain is classified into letters and syllables used to construct written

texts, etc.

In the US, at least, we have a now trite expression "Don't

give me a song and dance" which is used derogatorily to mean "get to the point"

or "say it in plain English". In the West, at least, we want, generally, to be

spared the song and dance. We have scholars and experts to present ancient

knowledge to us in a more palatable form. Well, you get what you pay for so we

are left with the song and dance without the song and dance.

In order not

to "throw the baby out with the bathwater", (to use another now trite but easily

digested saying), a different approach is necessary. I have taken a different

approach. In order to adequately convey it, and to clarify why Mayan

hieroglyphics and the symbols in Chilkat dance blankets are analogous in their

use of "distributive abstraction", two questions must be answered with a "yes".

These are the questions. Do you really want to know? Do you want my song

and dance in your Salon? Sue

Posted by R. John Howe on 10-20-2003 03:32 PM:

Steve and Sue -

My own reactions are not much different from yours,

BUT in the second labeled drawing above, it seems to me (once the

interpretations of "tail" and "feet" have been given) that one can discern

"claw-like" forms in the second one that are not unlike either bird or bear feet

and the "tail" area does have a rectangular area that could be seen to be shaped

roughly like some bird tails. What is confusing to me (and the "face" drawing is

beyond me as a "body") is that there usually seems to be an "eye" form nearby

each design segement and it is often larger than the part of the design that

seems to be most representational.

Sue -

About your two questions.

Sure, if your analysis doesn't take us too far afield. I'll license myself here

to say so, if I think that occurs.

Regards,

R. John Howe

Posted by R. John Howe on 10-20-2003 09:23 PM:

Dear folks -

Wendel Swan has written me on the side, suggesting that

perhaps it would also be useful to look at some designs on Pre-Columbian tunics

and mantles from Peru.

He suggests that it might be even more appropriate

to compare the Chilkat designs with others in the Americas than it would be to

contrast them with those on the Turkmen asmalyk.

I looked around the

internet a bit and here are some sites that show a variety of ancient Peruvian

designs.

http://www.somtexart.ch/gallery/precolumbian1.htm

http://www.textilearts.com/precolumbian/

http://www.butterfields.com/areas/ethnographic/7437e/Pre-Columbian3.htm

http://exchanges.state.gov/culprop/peimage.html#textiles

http://www.textile-art.com/feath1.html

http://www.precolumbianart4sale.com/inv.asp?Category=TEXTILES&PageNo=1

http://www.culturalexpeditions.com/history_peru_textiles.html

http://www.wfu.edu/wfunews/2003/031703t.html

I will

leave to others the possible identification of similarities with aspects of

Chilkat design, but I did not encounter, I think, any that seem to me to be of

the "distributed" variety.

I am hoping that Wendel will share his

observation directly with us here.

Regards,

R. John Howe

Posted by Sue Zimmerman on 10-22-2003 01:22 AM:

Hi,

Long ago, it is said, some people had ancestors who lived in a

very damp place where it rained all the time. Their bones never had a chance to

dry out so they had really big problems with joint pains. They found that

dancing helped their health. They developed medical treatments which

incorporated different movements and breathing techniques, etc., one of which

was called "bonemarrow/brain washing", which made them feel better. They

designed different styles based mainly on their observations of various animals,

to help with various energy flow problems. One amongst these was called "Tu Go

Naxin". "Naxein" is what the Chilkat's call their dance blankets.

The

Chilkat dance blankets display what is being called "distributed abstraction"

because they are Qigong medical diagrams charting the metabolic pathways of Qi

energy. Untill quite resently the finer points of Qigong were not made public

and were passed down, generation to generation, secretly.

The Mayans, I

have found, had their version, too. Theirs is probably closer to the source

though because it is much more sophisticated in that it includes histology, zoom

in and zoom out views, and where exactly in the brain such things as speech and

hearing are processed. I know this because once I figured out the system I was

able to find the same stuff in modern medical books. I'm betting it is pre-Mayan

but I have more work to do on this before I know that.

I could explain

more but it would be a very technical technical workshop and exactly the sort of

thing which might be thought too far afield. I think it is interesting though.

Sue

Posted by Stephen Louw on 10-22-2003 04:23 AM:

Dear Sue

I am interested in your statement that the Chilkat dance

blankets include "Qigong medical diagrams charting the metabolic pathways of Qi

energy".

To the simple minded, like myself, this begs more questions

than it answers. What evidence, for a start, can we base this observation on? Is

this simply the fact that people previously committed to secretly passing down

this ancient wisdom have decided to break ranks and share this insight with the

general public? Or is there a more reliable basis for this atribution?

Posted by R. John Howe on 10-22-2003 04:24 AM:

Dear folks -

Sue Zimmerman suggests that the designs on Chilkat

dancing blankets may be in part a reflection of some traditional medical

practices that existed in both Chilkat society and in ancient ones in South

America.

A few years ago, the Sackler Museum here in Washington, D.C. had

an exhibition of Tibetan paintings of the human body, used in traditional

Tibetan medicine, that sound similar, to those Sue mentions above, if abstracted

quite differently. We have a daughter who is a nurse, but who has always been

attracted to naturalistic medicine and the pictures in the associated book were

so beautiful that we bought her one. I looked around the Sackler site to see if

I could find an example, but could only find the more geometric "mandala" figure

that is not a literal drawing of the human body.

But, as Sue says,

traditional societies had "pictures" of the various aspects of the body that

they used in their healing practices. The Tibetan traditional medicine above had

its counterparts in China and India, likely, in part, because of its Buddhist

character.

As you can likely tell, my own exploration of the origins of

the Chilkat dancing blanket designs has been quite circumscribed, but I have not

detected any hint in any of the stories told about it in the literature what

would suggest that they were related to Chilkat medical practices in some way.

Instead the root story of the origin of the Chilkat formline weavings, seems to

actenuate famine (although the reference may only be to winter) and relief from

it, with the addition of what might be called, "the girl weaver gets a prince"

wrinkle, that also seems to suggest the origin of the giftgiving

potlatch.

Here is Samuel's rendition of how the Chilkat dancing apron

(notice not yet a "blanket") orginated. You can find variations in some of the

links I provided in the initial salon essay.

"On the banks of the Skeena

River in a Tsimshian village lived a widow with her young daughter. Although the

dark days were growing lighter, deep snow still blanketed the ground and gowned

the trees in ermine robes. The people and the animals were hungry, for the

season's stores were low and no food was to be found on the frozen

land.

"The fire in the center of a great chief's house burned slowly as

day by day the young girl sat, facing the painted screen in the rear of the

house. Beautifully carved and painted with a myriad of small figures, the screen

told of the greatness of her clan and of a time of leisure and plenty. Day after

day she gazed at the screen, mesmerized by the figures as they flickered in the

firelight. Day after day she suffered from the pain of her hunger. There came a

time when the figures on the great screen took possession of her, and forgetting

her hardships, she began to weave a waist robe filled with the forms in the

firelight.

"Slowly, the weaving grew; slowly, the snows melted. The

spirit of spring spread itself across the land, swelling small buds into

blossoms and broadening the bellies of women. Working the designs of her men

into soft wollen strands, the young woman wove, creating an apron of subtle

beauty. When the weaving was completed she attached it to a caribou hide and

added layers of leather fringe. While listening to the melting snow, she

carefully sewed puffin beaks, each with a tiny feather inside, in a flowing

curve beneath the weaving. To the tails of the bottom row of fringe, she sewed

clattering deer's hooves. The apron was finished. As she moved to wrap it

carefully in intestine cloth, the rattle of the beaks spoke of the melting snow

and of the summer that was soon to come.

"The summer did arrive, and with

it the son of the chief, seeking her hand in marriage. Greatly honored, she

presented the apron to his father. To validate the privilege of owning such a

beautiful garment, the chief gave a feast, sacrificing many slaves and dancing

in the apron. People marveled that such a masterpiece could be created in wool,

its fame spread throughout the land and commissions for similar garments came to

the woman. She and her mother shared the secrets of the weaving with the women

around them, and in this way the Tsimshian became renowned for their creation of

the exquisite Dancing Apron."

Notice that there is no mention in this

tale of any "crest" animal, nor is there any role of such an animal in bringing

spring. The designs already exist, so the relationship with any crest animal

pre-dates this story and the creation (in fable) of the first Dancing Apron.

Perhaps there is a medical implication in these designs, but it has not been

visible to me in my reading so far.

Regards,

R. John Howe

Posted by R. John Howe on 10-22-2003 04:47 AM:

Dear folks -

In considering Chilkat formline designs, in this thread,

it might be useful to be sure to read the analysis of it in this link that I

provided in the initial salon essay:

http://www.chiefseattle.com/books/art/analysis_of_form/analysis_of_form_sample.htm

Now

this is primarily a comparison of scholarly views, not necessarily those of the

Chilkats and related tribes themselves, but Emmons and others did do field work,

and so can often report what Chilkats did say their designs

represent.

Note in this respect, that there are indications in this link

that Emmons (and perhaps others) found contradictions between Chilkat

interpretations of particular the designs. If so, that would provide a basis for

one species of critique that I have suggested could be legitimate: that a given

species of abstaction was not successful in the sense that its ambiguity grew to

such an extent that its root meanings could no longer be reliably described by

the Chilkats themselves.

Regards,

R. John Howe

Posted by R. John Howe on 10-22-2003 04:58 AM:

Dear folks -

And here is a paragraph by Emmons on Chilkat design

explaining in part what various aspects repesent and answering to some extent

the question of "why are there seeming "eyes" everywhere in Chilkat

designs?

"...The patterns were a highly stylized form or art often

representing clan symbols and natural forms in an abstract geometric pattern.

Animals were portrayed as if sliced down the center and laid out flat. The small

circles are ball and socket joints. Eyes were often used as space fillers. The

men designed the pattern and painted the abstract figures on a wooden "pattern

board." As the blanket was bilateral, only half the pattern was painted in

life-size dimensions. The blanket pattern could be interpreted in a variety of

ways, however only the man who designed the blanket knew the true

legend."

Emmons' suggestion here that the small circles are ball and

socket joints is the closest indication I have found to Sue's suggestion which

also referred to "joints."

Regards,

R. John Howe

Posted by R. John Howe on 10-22-2003 06:18 PM:

Sue -

I put "naxein" into a Google search and got this at a couple of

sites:

"Beautiful Chilkat blankets are used as dance robes. The fringe

provides a wonderful visual effect as the dancer moves. (The Tlingit name for

the Chilkat blanket is Naxein, meaning "fringe about the body.)"

Your

original indication of this term seemed to relate it somehow to a health purpose

of some sort. Here are a couple of your sentences in that post:

"...They

designed different styles based mainly on their observations of various animals,

to help with various energy flow problems. One amongst these was called "Tu Go

Naxin". "Naxein" is what the Chilkat's call their dance blankets."

How

does one decide that a word that is indicated as referring merely to "fringe

about the body" has implications for some sort of therapuetic dancing? I'm

missing the connection in these seemingly similar words.

The Chilkats

certainly had theories about life and death and health and illness, but I've not

seen other suggestions that they are reflected in the Chilkat designs or in

Chilkat dancing.

Regards,

R. John Howe

Posted by Steve Price on 10-23-2003 06:46 AM:

Hi Sue,

I'm having lots of trouble sorting out what you're tryng to

say here. I'd be grateful to you if you will clarify it. Please use simple,

direct forms of expression.

quote:

Originally posted by Sue Zimmerman

Long ago, it is said, some people

had ancestors who lived in a very damp place where it rained all the time.

Their bones never had a chance to dry out so they had really big problems with

joint pains.

It may not be very important - some people do develop joint

discomfort in cold, damp weather - but your bones don't "dry out" under other

conditions. They're in an environment of constant, controlled humidity

regardless of weather.

quote:

They developed medical treatments which incorporated different

movements and breathing techniques, etc., ... They designed different styles

... to help with various energy flow problems. One amongst these was called

"Tu Go Naxin".

Am I correct in interpreting this as meaning that one of

their healing dances specifically involved wearing a dance blanket, and that

dance was called "Tu Go Naxin"? If I missed the point, please correct

me.

quote:

The Chilkat dance blankets ... are Qigong medical diagrams charting the

metabolic pathways of Qi energy.

Is there evidence that the Chilkat blankets are medical

diagrams, or is this something that you intuit on the basis of the fact that

their repertoire of uses includes at least one dance that is for healing? As a

side point, the notion of Qi energy is a peculiar one, certainly outside the

physical understanding of the concept of energy and outside the fundamental laws

describing the behavior of all forms of energy. Whatever it is (if real), and

whatever pathways it follows, they aren't metabolic pathways - that term has a

fairly specific meaning and is used to describe the steps in transformation of

one chemical species into another (glucose into carbon dioxide and water, for

instance; glucose into fat for another).

quote:

... Mayans ... is much more sophisticated in that it includes histology

...

You can't actually mean what this appears to say. Histology

is the microscopic study of tissues, and cannot exist in the absence of some

instrument that permits this to be visualized (like a microscope). Nothing like

this existed in the Americas. So, you must mean something else. What?

quote:

... and where exactly in the brain such things as speech and hearing

are processed.

Color me exremely skeptical about this statement. if

there's anything to it, it's simply astonishing.

quote:

I think it is interesting though. Sue

I agree.

Regards,

Steve Price

Posted by R. John Howe on 10-30-2003 03:46 PM:

Abstraction in Some Peruvian Designs (Long)

Dear folks –

Last weekend, I encountered a book in a local flea market

that let me explore somewhat further Wendel Swan’s indication that he thought he

had seen some ancient Peruvian designs that resembled those in the Chilkat

dancing blanket.

The book is “Ancient Peruvian Ceramics: The Nathan

Cummings Collection,” by Alan R. Sawyer. The book was published by The

Metropolitan Museum of Art in 1966. Because the book focuses almost entirely on

ceramics the arguments that can be made based on it must by analogy, although

the “South Coast” ceramics that seem to exhibit the most complex instances of

abstract design were often found in burial sites where textiles were also

discovered.

Before I begin with the designs I want to mention one other

cultural feature of the South Coast Peruvians: they bound the heads of women to

give their foreheads a sloping shape. Perhaps entirely by coincidence, the

Chilkats also practiced similar heading binding to achieve a similar

effect.

But to the ceramics. Peruvian ceramics are divided into those

made in North Coast areas and these are distinguished from those made on the

South Coast. The designs on the North Coast ceramics are quite realistic, while

those of the South Coast include complex abstraction. I am going to show you

several instances of the latter, referred to as “Paracas,” which is a peninsula,

and to give you the associated descriptions from Sawyer’s text.

(There

will be occasional references to the “Chavin” period or to “Chavinoid”

characteristics. These refer to an earlier period, the stylistic tendencies of

which continued to influence to some extent the ceramic designs of both the

Peruvian North Coast and South Coast.)

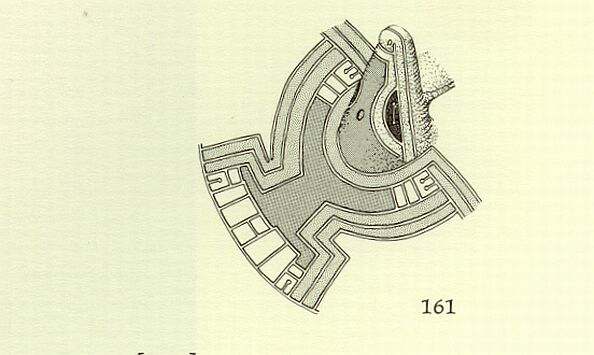

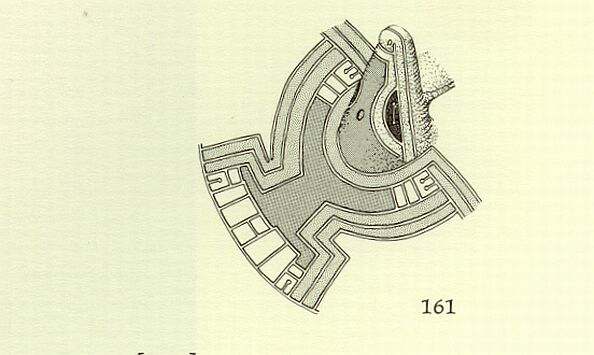

Sawyer indicates that this

design is from the border of a mantle. Here is his description of

it:

“…It bears the reverse-repeat of a complex monkey figure with long

serpentine tail and similar head ornament, each having saw-toothed edges and

ending with a trophy head like the one held in its hand. A larger trophy head is

pendant to the chin, and within the body is a cat or monkey figure, which in

turn contains a small feline. Small human, animal and bird figures are used as

background space fillers…”

This abstract design seems still to be one in

which the basic form of the “monkey” creature can be discerned but there are

lots of motifs placed about it in ways that violate realism considerably and

there are devices repeated and placed without regard to their anatomical

location in life.

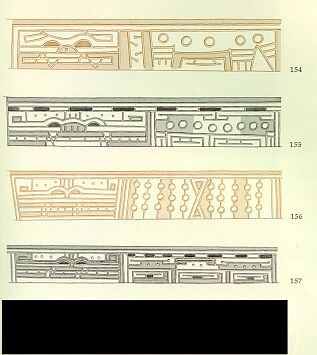

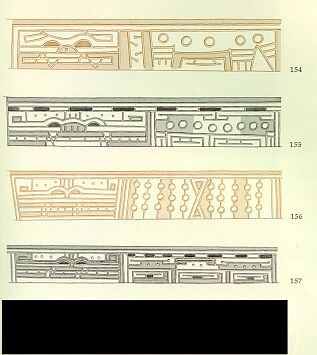

Here from a somewhat later period are some “feline”

designs (cats are big in these Peruvian ceramics) that show a progression in

abstraction.

Here is Sawyer’s description of this progression in a feline

figure:

“…The Phase One example (154) shows a simplified frontal mask

with emphasis on canine teeth. The body has a Chavinoid eye pattern between the

legs (resembling the position in modeled version) and a triangular

hat.

“The second-phase version (155) show a considerable advance over the

first. Both mask and the body are widened and more elaborate. Two Chavinoid eye

patterns now appear below the body, and the tail may be represented by the two

elements with curled ends above the back.

“Our third-phase example (156)

shows a variant in which the body panel is represented by pelt markings alone,

with the tail evidently represented by a conventionalized guilloche, shaped like

an hour glass, in the center. The nose has been eliminated and the canine teeth

reduced to parallel lines.

“The final Early Paracas phase is represented

by rendering in which both face and body elements are further attenuated and

abstracted (157). The body consists of three eye patterns with tail elements

above, but the paws on the legs have been eliminated.”

Now I don’t know

anything about these ceramics or their designs at all, but while the designs do

seem to feature a “Mondrian-like” paring down of elements and even their

omission sometimes, the figure still seems “readable.” Attenuation and

abstraction are considerable but there is not much actual displacement of body

parts a la the Chilkat distributed abstraction usages.

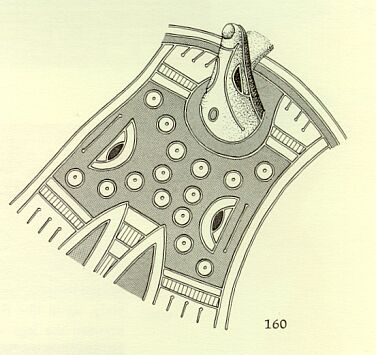

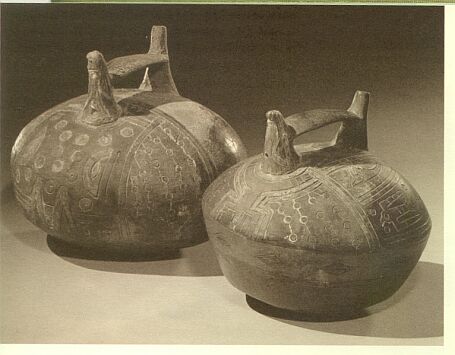

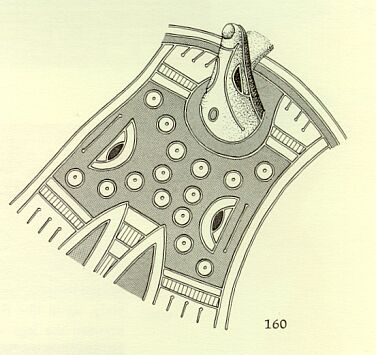

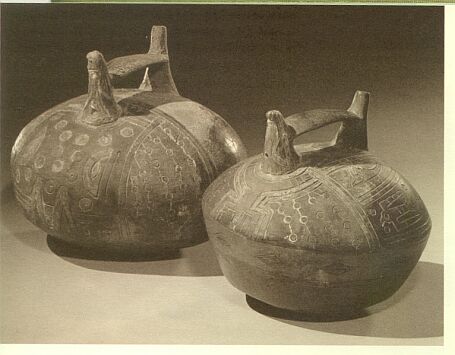

The next example

is from an even later date. It centers on a “fox” motif. It is one that does

have some aspects of Chilkat Dancing blanket graphic designs.

Here is Sawyer’s

description:

“…The blind spout is in the form of a long-snouted fox head,

and the figure is incised on the body of the vessel, spread out like a pelt

stretched for drying. The forelegs surround the head spout, while the hind legs

and the tail hang down the gambrel.”

Here is a second example of this

type.

I want

to be clear that these are designs on items of ceramic that have a 3-D form.

Here is how they occur on an actual item of Peruvian ceramic.

‘…On the earlier bottle there

are Chavinoid eye patters on each side of the pelt, give it the appearance of a

frontal fox mask, in which the tail element becomes the snout. The body in the

later version is constricted, but in both cases the modeled head makes

identification of the fox comparatively easy.”

And again, I am out of my

element daring to comment on these designs and on this commentary, but it seems

to me that there are potentially three features of Chilkat dancing blanket

designs in these two examples.

First, the animal has been divided, head

to tail, and opened up into halves. This is one of the major moves the Chilkat

artists made in their abstraction of their animal designs.

Second, we

seem to have “eye” forms in places where “eyes” do not ordinarily occur in

nature. And the fact that Sawyer provides a rationale for their meaning seems

not to touch at all their odd placement.

Third, it is not always clear

whether the design shows the animal in profile of head on. Multiple readings are

possible despite that rather unambiguous “head.”

So these two examples

do seem to have some features that resemble Chilkat usages.

By now, you

may be getting a bit weary of these sequences, but bear with me for one more.

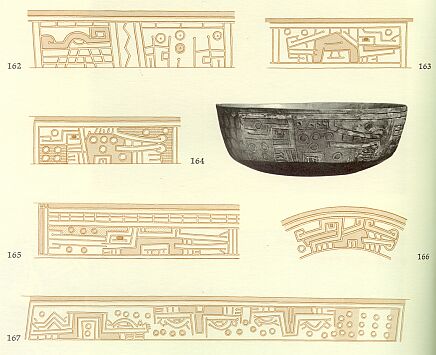

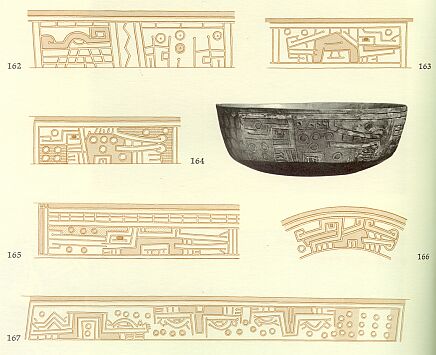

Here is another sequence of ceramic designs based on a fox motif.

Here, also, is Sawyer’s

interpretation of them.

“…The highly abstract profile is divided into

head and body panels, similar to feline motifs. The head is in profile…but

without the foreleg below the jaw. The nose, brow, and ear are unified into one

element. The body…has both circular pelt markings and eye patterns between the

legs---no doubt a deliberate endowment of the fox, with feline attributes, as we

have seen to be the case with the falcon and serpent designs.

“By the

beginning of the second phase of Early Paracas, the fox had undergone

considerable transformation (163). The two panels unite to form a single profile

figure and the foreleg reappears below the jaw, which now lacks teeth. The eye

of the head matches the Chavinoid eye beneath the body, and the foreleg is

balanced by a hind leg beneath a triangular tail. Pelt marks are used as space

fillers in the background.

“A variant of the third phase (164) displays a

tendency toward abstraction, though the relationship of the feet with the long

snout and tail is retained. Pelt marks appear both on the body and in the

background.

[ed. In] “The fourth phase of Early Paracas (165)…The fox is

elongated and compressed below a band of teeth motifs. The small pelt-marking

circles are restricted to the background above and below the long

snout.”

“…A more unusual fox motif …(167) is…decorated with motifs made

up of two half-fox figures, joined back to back and inverted to form a human

mask… Again we encounter the Paracas penchant for double meaning.”

OK,

what can we conclude, if anything, from these Peruvian examples?

It

appears that the designs on the Peruvian ceramics that indulge in the greatest

abstraction…that of the Paracas, of the South Coast, do have some features that

are similar to the abstraction deployed by the makers of the Chilkat dancing

blanket. Paracas ceramic designs are abstract, sometimes very abstract. Some

instances of them do divide the creature down the middle head to tail and open

out the two halves. There is also a frequent use of “eye-like” devices, and some

of these turn out to be actual eyes but others seem to be pelt marks. There seem

to be “eye” forms in places where neither actual eyes nor actual pelt marks

occur on the animal. There is apparent use of some small motifs as filler

devices unrelated to natural representation. Last, the designs in the Paracas

ceramics seem sometimes to be deliberately ambiguous. Sometimes animal parts are

shown in profile and at other times head on and some usages invite multiple

readings. These latter usages could be seen to be instances of “distributed

abstraction.”

But most of the tendencies of Paracas ceramic designers

seems less extreme than do those of the designers of the motifs on the Chilkat

dancing blankets that exhibit “distributed abstraction.” There seems not much

question, usually, about what animal is represented by a given Paracas

design.

I conclude that while the Paracas ceramic designs do exhibit some

features of “distributed abstaction,” they are quite distinct from, and a much

milder species of this sort of abstraction, than that which the Chilkat artists

practiced.

Regards,

R. John Howe

Posted by R. John Howe on 10-30-2003 08:41 PM:

Two Obscure Words

Dear folks –

It has been noted here, sometimes, that I am visibly

interested in obscure English words. And I plead guilty. It is one reason why I

read and reread Michael Innes’ murder mysteries. In each of his books, Innes

manages to slip a few words into the seeming ordinary parlance of his characters

that you and I have never heard anyone use in either our own or overheard

conversations.

This post is by way of acknowledging and clearing up two

potentially obscure words that occur in the post immediately above this one.

They are words that Mr. Sawyer, the author I have quoted there, has used, but

since I am the one who has put them in front of you, I bear some responsibility

for avoiding confusion about them.

The first word is “gambrel.” Sawyer

uses it in the paragraph below the image labeled “160” and I think he means it

to indicate “leg.” If that is so, I think he should have said so more

directly.

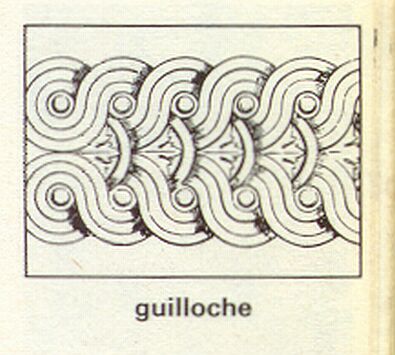

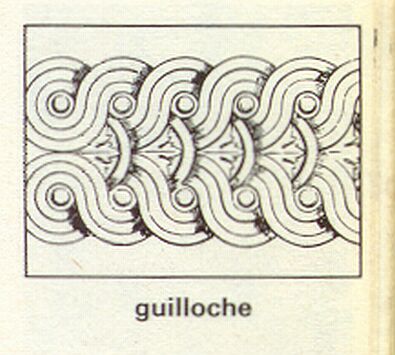

The second obscure word Sawyer has used is potentially more

interesting. It is the term “guilloche.” Sawyer uses this word in his

interpretation of image 156. My dictionary says that it is an architectural term

and refers to “…An ornamental border formed by two or more bands interlaced in

such a way as to repeat a design.” Here is an image of one example of a

guilloche:

I don’t recall off hand, a border pattern that exhibits these

precise features (Caucasian “butter churn” borders have this outline and are

composed of elements that fit into one another in similar ways) but perhaps

someone else will offer a closer example.

You are now equipped to reread

the post above more transparently than perhaps you did

initially.

Regards,

R. John Howe

Posted by Filiberto Boncompagni on 10-31-2003 04:02 AM:

Hi John,

It looks like there are similarities between those designs on

Peruvian ceramics and on Chilkat dancing blanket. Some common cultural roots

perhaps…

What about ancient Peruvian

textiles?

Regards,

Filiberto

Posted by R. John Howe on 10-31-2003 07:39 AM:

Hi Filiberto -

There are certainly books on early Peruvian textiles

but I don't own any, partly because I've always had trouble with fact that they

all come from burial sites and that seems like a species of "grave-robbing" to

me. Others obviously see that differently.

But to answer your question

directly, the ceramics Sawyer discusses in this book are mostly from large

burial sites in which (he says explicitly) there were also textiles. In fact the

first image in my post is from a "mantle" which is a kind of textile. I think

mantles were wore about the shoulders. So I tried to say (perhaps not clearly

enough) that I think that the designs on the ceramics are likely similar to

those on the textiles of these people.

Someone may have a book on

Pre-columbian textiles that would permit specific confirmation of that suspicion

but I don't.

Regards,

R. John Howe

Posted by Filiberto Boncompagni on 10-31-2003 08:11 AM:

Hi John,

I knew the first image was from a mantle, but, as you said,

it was only from the border of it.

What I’d like to know is if the same kind

of organization of space/design or "Distributed Abstraction" existed in the

"field" of Peruvian Textiles - especially mantles: Chilkat blankets were used as

short mantles after all.

I understand that you don’t have the answer to

that question, though. Maybe somebody else…

Regards,

Filiberto

Posted by R. John Howe on 10-31-2003 08:24 AM:

Filiberto -

I just did a quick Google search for "Peruvian textiles

Paracas" and got a few links that do show similar designs on the associated

textiles.

Here are a few of the links:

http://www.precolumbianart4sale.com/inv.asp?Category=TEXTILES&PageNo=1

http://www.culturalexpeditions.com/history_peru_textiles.html

http://www.barakatgallery.com/store/index.cfm/FuseAction/ItemDetails/UserID/0/CFID/467425/CFTOKEN/39580405/CategoryID/31/SubCategoryID/846/ItemID/6697.htm

http://www.locstore.com/pecabo.html

And here is a link

to a book that seems likely:

http://www.uiowa.edu/uiowapress/pauparart.htm

Regards,

R.

John Howe

Posted by R. John Howe on 10-31-2003 08:43 AM:

Filiberto -

Here is a link from a search on "Paracas mantles."

http://exchanges.state.gov/culprop/peru/textile/0000001e.htm

Note

that the text below describes the various designs. Some fields were apparently

plain but others were decorated.

Here's another:

http://www.artic.edu/artaccess/AA_Amerindian/pages/Amerind_9.shtml

Note

that many designs were embroideried rather than woven.

A few

more:

http://www.brooklynexpedition.org/latin/code/co_mantle_index.html

http://www.dallasmuseumofart.org/edu/teachingpackets/TP/ArtofAmericas/Artwork/AmerMantle.htm

http://www.picturesofrecord.com/south%20american.htm

http://www.turifax.com/photogal_prcas.html

There are

apparently quite a few images up on the internet. (Music on the last link is

just extra.  )

)

Regards,

R. John Howe

Posted by Filiberto Boncompagni on 10-31-2003 09:52 AM:

Thanks,

No, the designs on the mantles do not recall the Chilkat blankets

as the ceramics do.

I also had a look to the "small shoulder ponchos": same

conclusion.

Filiberto