The Salon du Tapis d'Orient is a moderated discussion group in the manner of the 19th century salon devoted to oriental rugs and textiles and all aspects of their appreciation. Please include your full name and e-mail address in your posting.

Islamic Textile Art and how it is Misunderstood in the West - Our Personal Views

by Muhammad Thompson & Nasima Begum

Summary: Islamic art in general is poorly understood and the appreciation of Islamic, Moroccan textiles is a case in point. Western markets seem more prepared to recognise the pre-Islamic and pagan origins of kilims than they do the influence of Islam; this anthropological approach misconstrues the art as backward rather than progressive. Reference is made to a number of misconceptions in the literature - barakha, jinn, alms and marriage dowries - and an Islamic interpretation offered to assist readers in developing a truer appreciation of these textiles, which deserve a place in any comprehensive account of 20th century art.

Western attitudes towards Islamic art are often based upon misconceptions, and muslims may have done little to dispel these. While the west spurns the religion it places high value upon its artefacts. But knowing little of the religion the West buys both the rugs and the stories spun about them. Many prayer rugs in the oriental rug market are unlikely to have been intended for prayer and some have been manufactured (even by non-muslims) to exploit the western notions and markets for “the muslim prayer rug” (discussed in more detail in a recent Salon).

There is a tendency among oriental rug collectors and writers to view these textiles as tribal and primitive as opposed to decorative/aesthetic and meditative; to look to the Amazigh (Berbers) as a pastoral people rather than as amongst the builders of the high art of Marrakech, the Alhambra and Muslim Spain. This western view is condescending at best.

This is not to say that the lives led by makers of these rugs aren't both tribal and pastoral. And Morocco, as well as other countries where kilims are still made, is today less developed than the countries where these textiles command high prices.

But the Moroccan women who have made these kilims suffer no deficit in imagination or religious devotion and we might get more in our appreciation of their work if we credit them with more than just a tribal re-working of ancient symbols. To get the most from these rugs, we might concede that their makers are capable of a high level of abstract and devotional thought.

In their otherwise excellent description of kilims (2) and those who make them, Hull & Luczyc-Wyhowska (1993) fall into this trap on occasion:

“The Berbers are one of the few remaining animistic cultures in all Africa, and while Islam prohibits representational motifs, the Berber universe - a realm dominated by the forces of the sun, moon, stars, plants and animals - forms part of their artistic vocabulary.” (page 61)

Delacroix observed Moroccan people and came to a quite different conclusion

in the nineteenth century - “They are closer to nature in a thousand

ways, their dress, the form of their shoes. And so beauty has a share in

everything they make. As for us in our corsets, our tight shoes, our ridiculous

pinching shoes, we are pitiful."

African or Oriental?

Within the western market for oriental carpets, Moroccan rugs are apparently not valued in the same way as work from Turkey, Iran and Afghanistan. Hull & Luczyc-Wyhowska consider Moroccan textiles to be “less significant” - a statement that would appear to warrant some explanation. Perhaps their designs are less floral and organic than their eastern counterparts; they are more African and consequently less “antique”; they then fit more comfortably into the idea that African art is somehow more pagan, more functional, more backward looking than its Middle Eastern and European equivalents. At the beginning of the twenty-first century, our eyes educated by Gaugin, Matisse, Delacroix and Picasso, we ought to be in a better position to view the arts of the world with a less orientalist or anthropological caste.

But it upsets the historical narrative if we must acknowledge that the European Renaissance would not have been possible without the high art, science and learning passed to it by the Muslim libraries of Toledo and Baghdad; that the renaissance would have been less likely had the rulers of Europe succeeded in obliterating the Muslim heritage.

This ambivalence was and is evident in the western appreciation of the Alhambra as a “pleasure palace”. To the minds of westerners it was inconceivable that the splendour of these courtyards could serve any religious purpose. If Washington Irving can be said to have played an important role in preserving the Alhambra it was done by titillating the readers imagination with stories of luxury and passion.

But many among the millions of people who visit this remarkable Palace, easily understand the purpose of those Muslims and return to their own small gardens inspired to create in them the small haven of peace and contemplation which the Alhambra so wonderfully achieves.

Islamic art is a Trojan horse in the midst of western society, it is neutralised by regular and ritualistic assaults upon the ideas behind it; we are allowed to appreciate the decoration of the Alhambra (with verses from the Qu’ran) but our guides do not trouble us with the meanings of these words and allow us instead, flights of fancy.

And whilst the renaissance is partly seen as a triumph of reason over religion, how can Europeans accept that the fruits of Islamic learning were obtained by a totally different path or that the Christian churches were in some way regressive whereas Islamic society nurtured the intellect?

The western historical narrative rests upon the idea that progress comes from a separation of Church and State and from this will follow democracy, freedom of the individual, freedom of speech, primacy of law and science ... in this view, (as recently expressed by Sr. Berlusconi), Islam cannot be right because it is medieval in its insistence upon the unity of state and religion.

When we look at these textiles we must resist any temptation to look down upon the society which produced them and put aside a purely western interpretation of history. Instead of idealising pastoral societies we can examine and learn the values of these communities through their art and religion.

The Qur’an, sura 16 (ayat 80),

The Bee

bismillahir rahmanir rahim

It is Allah Who made your habitations

Homes of rest and quiet

For you; and made for you,

Out of the skins of animals,

Tents for dwellings, which

Ye find so light and handy

When ye travel and when

Ye stop in your travels,

And out of their wool,

And their soft fibres

Between wool and hair,

And their hair, rich stuff

And articles of convenience

To serve you for a time.

A personal view

We travelled to Morocco after visiting the Alhambra and the imagery of those courtyards, the endless decoration of its high walls, the way the buildings hover between the sky above and the pools of water at your feet, how gardens have been calmly laid out and tended inside the building whilst beyond their walls the ragged slopes are of wildest nature, the jewel-like construction of ceilings, domes and walls and then from a window your eye is drawn toward the Sierra Nevada mountains laced with snow and sun...... it is a Qur’anic recitation in stone, with the same images of paradise being evoked to allow meditation upon the next life.

The Qur’an

sura 88, (ayats 8 -16)

The Overwhelming Event

bismillahir rahmanir rahim

Other faces that Day

Will be joyful,

Pleased with their Striving,

In a Garden on high,

Where they shall hear

No word of vanity:

Therein will be a bubbling spring:

Therein will be couches

Of dignity, raised on high,

Goblets placed (ready),

And Cushions set in rows,

And rich carpets

All spread out.

As muslims we were naturally interested in the people who had built the Alhambra - where they had come from, where they went - and we travelled into Morocco wanting to know more. When we started buying Moroccan hanbels, a dealer in Saharan Amzrou asked us what it was we were looking for in a kilim. He had not been to the Alhambra but we tried to describe the impression it had made on us and how we looked for some of these qualities in the kilims: restrained use of colour, energetic design embellished with fine decoration.

We travelled northwards along the Draa Valley and crossed the High Atlas to Marrakech just as two months earlier we had driven up to Granada nestling in the plains of the high, snow-capped Sierra Nevada. The forebears of those who had once ruled Spain, made Marrakech their capital and built there in the style of al Andalus using Andalucian craftsmen. If our education in kilims began in Saharan Amzrou, (where the quality of the kilims are judged in part by the tightness of the weave so as to exclude sand passing through), it was rounded off in Meknes and nearby Azrou when we started to see Zaiane and Beni M'Gild hanbels.

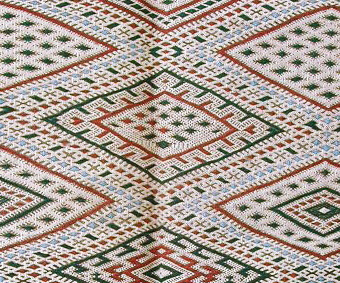

There is a freedom of expression and a boldness of design in some of them which is emphasised by the many irregularities found in the working patterns. Reduced to its most fundamental, you might say all Moroccan kilims are a variation on the diamond motif, and these Zaiane pieces testify to this. Yet they are not boring, rigid, repetitions on one theme. The motifs do break out of the rugs two dimensions and offer a new perspective for the eye; a glimpse of a space outside this world.

In this, these carpets approach the true purpose of Islamic art: like the Alhambra, they offer the beholder a way of contemplating the greatness of Allah. Islamic art needs to be non-figurative and it is most often employed in decoration, playing with geometric figures capable of endless extension to suggest realities beyond the earthly.

Anomalies in kilims

One of the questions we always posed to rug sellers was: how do mistakes arise in a kilim? You can find many examples where the pattern has been broken in such a deliberate way that it cannot be a mistake. “Only their maker knows this”, was the common reply. One seller in Meknes however, believed that the weavers, devout Muslim women, would not be so arrogant as to even attempt a “perfect kilim” since such perfection belonged only to Allah. Consequently, they would deliberately break the kilim’s patterning as a mark of their humility. This suggests the kind of devotional and contemplative energy which can underlie a kilims’ manufacture and design.

“’ atomism’ .... is the notion that all things, living or not, are made up of combinations of exactly identical atoms. The composition of atoms into “things” it is argued, is a divine prerogative, but artists or artisans, who must not compete with God, are allowed to organize these atoms in any arbitrary way they wish. Thus the free and imaginative variations of Islamic ornament or unusual combinations of motifs were seen as reflections of a philosophical doctrine on the nature of reality.” (O. Grabar) (3).

Westerners including Muslims in the west, are sometimes likely to misrepresent art of this kind - valuing the rug for the integrity of its manufacture or the use of ancient symbols to articulate a pattern. The Moroccan rug sellers are well aware of this bias in their western customers and are only too happy to describe the meaning of certain symbols within the rugs design. We are happily led on ...

We think there are good reasons not to subscribe to this anthropological approach - we doubt that the makers of the kilims any more than the western buyer, actually believes in the efficacy of these symbols, they have instead found in these geometries a rich vein for their imaginations as well as a means of restating their identity. In the better pieces they are looking forward rather than backward, to the next life described in the Qur’an.

That is why we have sought to persuade people to look at some of these kilims as if they were paintings or sculpture rather than tribal weavings. They won early admiration from Delacroix, Gaugin and Matisse and are valued in the American markets more than in Europe perhaps because of their painterly qualities and America’s delight in abstract art. Typical of the American market is a readiness to judge kilim designs and colouring in the same way as the other visual, fine arts and the modern, abstract art traditions of America provide them with ready benchmarks for the Moroccan textiles. Two landmark exhibitions of Moroccan textiles have been staged by the Indianapolis and Washington museums.

Some Examples of Anomalies

We can detect many different types of anomaly - some of these may even be the real thing - mistakes! But many appear quite deliberate breaks in a pattern or convention.

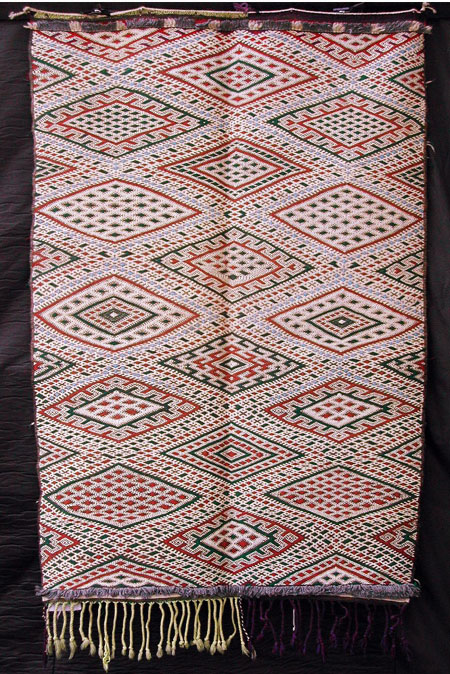

The central field and the border seem to be competing in places for the upper

hand in this Beni M'Gild rug. This kind of looseness or freedom

in execution of the design, may represent one type of anomaly. It makes

the viewer's eye and brain work. It is almost a device to suggest

that the real

design does extend beyond the convention of the border. The rug might

be likened to a sketch or a study - but in this case the masterpeice is

never attempted nor is it attainable in this life. The design inspired

in this

weaver is a hint of the inconceiveable beauty of the next world and she

makes

no attempt to constrain the pattern or make the rug appear too self-contained

or self-sufficient.

The border in this Beni M'Gild kilim is again where the weavers work becomes irregular, ambiguous. The rug is composed of three areas which are separated by thin bands as can be seen. There has been no attempt to bring the pattern to a timely conclusion at the boundary between two areas. Instead, the impression is created that the pattern continues - what we are seeing is just a snatch of the larger, more beautiful jewelled field which the weaver has glimpsed.

This fine Zaiane hanbel has an anomaly at its very centre. This piece

has been very carefully constructed and the design rules followed with

only one

exception: the colouring and the number of design

elements in the central diamond. This type of anomaly is not usually noticed

by the eye; it is not a feature of the work as it is in the Beni M'Gild

rug discussed above. It is a relatively small and deliberate sign that

the work

is an imperfect rendering. It might be the type of anomaly which could

be used in a commissioned work where the weaver is anxious of being criticised

(or worse) for a mistake.

In this Ait Ouaouzguite rug the pattern from one field has been allowed to wander into its neighbour. It is a much more noticeable defect in the kilim's design than that above. It is difficult to believe that this might be a mistake on the part of the weaver.

Good and Evil in Islam

Unfortunately, much of the literature describing the manufacture and history of kilims contains misconceptions of Islam or, worse still, ascribes their production and design to the pagan beliefs which the weavers and their communities gave up when they became Muslims thirteen centuries ago. In fact the “oriental carpets” which western markets prize so highly are the products of the Islamic Empire. Western writers on the subject seem to believe that the artefacts which they value so highly were made despite Islam and betray their maker's more ancient and pagan outlook; they rarely attribute to Islam a motivating force in the design and manufacture of kilims.

Thus, one website (http://www.kenzi.com), after providing a lengthy analysis of the ancient and pagan meanings of motifs found in Berber kilims, only finishes by saying: “Islam's influence on the Moroccan aesthetic was not merely one of constraint, rather one of celebration and devotion. Artisanal objects are created as an act of worship and tribute to God through the devotional work of a believer. In fact, the very act of decoration is considered a meditative practice bringing the artist ever closer to oneness with God.”

It is impossible to know whether the ancient symbols which are said to be found in the kilim still carry the meanings which have been ascribed to them. It does seem clear that nearly all kilim makers have wholeheartedly adopted Islam and that this most pure, monotheistic religion would have removed or diminished any belief in the efficacy of the symbols.

But if we can knock down one quaint and condescending notion of these peoples, another is thrown up in its place: this time the Muslims’ notions of baraka (from the Arabic for blessing) and jinn (from the Arabic for spirit people, both good and bad) are misrepresented so that they appear fertile superstitions inspiring the production of kilim makers rather than respectable, theological concepts from the mainstream of Islam.

These were ideas expounded by Westermarck in 1926 (“Ritual and Belief in Morocco”, referred to at pages 144-5 of “The Fabric of Moroccan Life”) (4) and demand revision if we are to approach a true understanding of the artistic and religious motivation for these flatweaves.

Barakha can be translated as God’s blessing; it is outside the power of the weaver or other Muslim to give any article this blessing - that is the prerogative of Allah alone. What is within the weaver’s power is to approach their work with a purity of intention and with the hope that their work will be blessed and bring rewards to its maker, its owner or the wider community. Islam stresses the importance of intention in all actions; it teaches that actions are rewarded according to their intentions. Thus, if a weaver intends to earn money by her work she will only receive a reward from Allah according to this intention. But if the intention is to earn money in order to sustain her family, this is considered more noble. Among the most noble of intentions is that of solely seeking the pleasure of Allah - by acts of worship which can include any approved action done for the sake of Allah. This is why Muslims begin most if not all activities with the basmillah - bismillahir rahmanir rahim, (In the name of Allah, the Compassionate, the Merciful). They seek to transform their whole life into an act of worship in which all activities are undertaken for God. This is achieved by acquiring knowledge of the religion and acting according to its strictures on all matters to do with daily life.

The Muslim’s conception of the jinn is defined by the Qur’an - it is not a pagan superstition but part of the Muslim’s belief. The Qur’an describes the two races that Allah created - man and jinn. Like mankind, the jinn can be good or bad. The jinn are made from fire where man is made from clay and Satan - the fallen angel, Iblis - is one of the jinn who refused to obey his creator and vowed to tempt mankind away from the true purpose. The Qur’an describes how Iblis tempted Adam and Eve and how many jinn seek the destruction of man’s soul. It is usual for the Muslim to begin any action with the basmillah and it’s counterpart - seeking refuge in Allah from Satan; all prayers and recitations of the Qur’an, begin with these two utterances and it is highly likely that they would also be on the lips of a weaver each time she started at the loom to focus her intentions.

Thus, the notions of barakha and jinn are elements of the Muslim conception of good and bad, purity and evil, beauty and ugliness ... and they are found in all things. Even the best things can become sources of evil - for example, family life if it results in making too high demands upon the individual can be destructive; a parent’s love for a child can be too compelling; the Muslim must balance all the different aspects of life to succeed and the life of Muhammad, the Messenger of Allah, is the best illustration of this.

This is why the “mistakes” we see in kilims have significance: were the kilim-maker to become too proud of her own skill, to seek perfection in her work and too great importance upon her own abilities and creations, this would place her in danger. To be an act of devotion her work needs to show humility, an acknowledgement that her skill is given by God, her materials and leisure provided by God ... any beauty which she creates from her labours is a small light from Allah, a hint of the unlimited beauty created by Allah in the next world.

Marriage Dowries and Alms

Hull and Luczyc-Wyhowska's description of these Muslim communities are sympathetic and we would only wish to pick up on a couple of comments which may mislead.

They say kilim manufacture is an important aspect of “alms giving” (when they speak of the kilim being given as a gift to the mosque). These alms (or zakat, one of the five pillars of Islam), are the Muslim tax upon all wealth. Zakat is given to the poor - but is sometimes given to the mosque to distribute amongst those in most need. It may be that mosques have come to own these kilims because they have been donated as gifts to the mosque or because the kilim has been given as zakat in lieu of cash (i.e., that the mosque should cash in the kilim in order to provide alms but that this might not be done immediately) - the kilims therefore fulfilled the requirement of a savings and banking system in these communities. This secondary purpose of a good kilim is still encountered in Morocco today - a fine rug is better than money in the bank: you get enjoyment from it and its value may appreciate without penalty (interest earned from savings is forbidden in Islam - it is considered little better than usury).

But these kilims would also be wonderful advertisements of their giver’s skills and generousity. We can imagine that a family in search of a good wife for their son might use the qualities of a kilim as one means of assessing their maker’s virtues. An array of kilims on a mosque floor would then take on a quite different significance. If this were the case, we might imagine that the maker would be more strongly motivated by a self-expression than the ancestral symbolism which provides the vocabulary of her art. Certainly H&W overestimate the value of the kilim as a dowry since in Islam the dowry is given by the man to the woman (in order to underwrite a degree of independence for the woman once married).

Is there any evidence that Amazigh communities have not followed this part of the shariah (Islamic law)?

Berber Tribes and the Role of Women

The concept of a “tribe” in the western mind, is dominated by ideas of a clearly defined group and region. In kilims we look for a common vocabulary of symbols which define the tribe almost as if we hope the textile can be read like a book to tell a story of pre-history. But the reality for these Berber tribes, seems to be quite different.

Berber tribes are segmentary....... “By this is meant a principle of symmetry in which a Berber ‘tribe’ splits into sub-groups, which are in turn divided into further sub-groups, down to the very small faction of the agnatic nuclear family. All that effectively defines any such tribe as an actual social unit is the belief in a common ancestor, whatever the actual genetic reality might be. Indeed, many segmentary tribes derive from more heterogenous groups or clans, whose union is based on the fact that they simply occupy the same piece of territory. Thus the idea of a tribe is a very fluid one, and a ‘tribal’ name may in fact apply to anything from a group of two or three clans to a huge group occupying a vast territory.” (p. 234, The Berbers, Brett & Fentress)

“ ... Berber women play a relatively important role in their communities, and have far more influence in decisions at all levels than the standard view suggests.” (p. 231, The Berbers, Brett & Fentress)

In the Moroccan textile literature there are possibly more equivocal attributions of rugs to tribes than there are unequivocal. In Morocco there is also room for dispute: what is a Beni M'Gild textile in Azrou that becomes the work of the Zaiane, 90 kilometres away in Khemmiset? To what extent can intermarriage account for this readiness to adopt the styles of another tribe? Could these weavers be as plagiaristic and referential in their designs as western artists? Whilst the weaver may be a member of her tribe, her work need not be tribal in any introverted sense we may tend to lend that term.

Conclusion

Zaiane, all wool, 1.58 x 1 metres

Beni M'Gild, wool and cotton, 2.85 x 1.48 metres

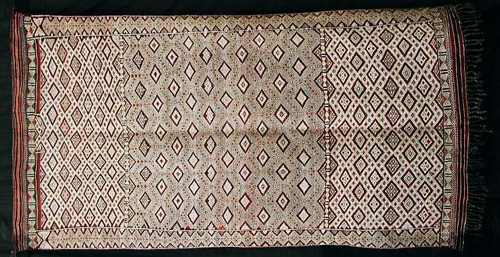

Beni M'Gild, wool and cotton, 3.75 x 1.67 metres

Look at the kilims (there are more at our website, Moroccan Hanbels) and make up your own mind.

Is this the work of women wishing to exploit a commercial opportunity?

Are they merely rehashing the geometries of their ancestors and some tribal

and pastoral history?

Are these God-fearing women using decoration as a medium for contemplation

of the divine attributes?

The chances are that you will be able to find in Moroccan kilims evidence of all of these traits of their makers. Some kilims are made in workshops with much more emphasis upon the value of commerce and wages than upon the religious views of the owner and the employee. Other kilims are truely unique and draw their inspiration from a tribal history and a most pure, monotheistic tradition.

Our contention is only that, at their very best, these textiles are very good Islamic art and that in order to appreciate this, the western eye needs to remove any sense of condescension for the religion or the society.

“ Islamic art is abstract, but also poetical and gracious; it is woven of soberness and splendour ... uniting the joyous profusion of vegetation with the abstract and pure vigour of crystals: a prayer niche adorned with arabesques holds something of a garden and something of a snowflake. This admixture of qualtities is already to be met with in the Q'uran where the geometry of the ideas is as it were hidden under the the blaze of the forms. Being, if one can so put it, haunted by unity, Islam has also an aspect of the simplicity of the desert, of whiteness and of austerity which, in its art, alternates with the crystalline joy of ornamentation.” Frithjof Schuon, (1969)

But if we have been critical of the West and the Oriental rug market for sometimes misrepresenting the art of Muslims, we are also in no doubt that the Muslim world is indebted to this market for preserving and nourishing this textile tradition.

We wonder how the market might further develop should western Muslims become significant patrons of this tradition? What if just a fraction of those Muslims who regularly pray upon, cheap factory produced prayer rugs, should instead buy a hand made kilim from North Africa, Afghanistan, Turkey and Iran? What better way to support these usually hard-pressed communities living in some of the most trouble-torn parts of the World?

References:

(2) Hull and Luczyc-Wyhowska, "Kilim: The Complete Guide" publ

1993 by Thames & Hudson

(3) Oleg Grabar in Islam Art & Architecture, edited by M Hattstein & P

Delius, publishers Konemann

(4) “The Fabric of Moroccan Life”, edited by N I Paydar & I

Grammet, published by the Indianapolis Museum of Art, 2002

(5) Brett & Fentress “The Berbers” (Blackwell Publishers,

1996)

(6) The Holy Qur'an translation and commentary by Abdullah Yusuf Ali

NOTES

Extracts from 'Kilim: the complete guide' by Hull and Luczyc-Wyhowska, 1993

The description of Hull and Luczyc-Wyhowska, 1993 (Kilim, Thames & Hudson) more fully recognises the role of Islam in the life of the kilim makers: “Almost all the weavers of the many and diverse tribes and groups featured in this book, are united by their Muslim faith. Although the flatweaving of rugs pre-dates the coming of Mohammed, the Islamic religion has given nomads and villagers a system of existence that, far from suppressing the believers’ artistry, has unleashed a flood of creativity in their arts and crafts ... The sophistication of the decorative arts of the Muslim world is reflected in the colours and the patterns of the kilims ... Yet most of the textiles ... are not commissioned by the wealthy court hierarchy ... On the contrary, they represent the work and wealth of communities living humble lives in harsh conditions.” (p. 8)

(p. 12) “The Islamic empires of the Seljuks, Ottomans, Safavids, Mamelukes and Berbers, were great patrons of the textile arts. These groups ruled the lands of the Mediterranean shores to Cathay between the seventh and eighteenth centuries and established a network of trade that extended from the Atlantic coast to the South China Sea; many of their enlightened rulers established workshops and gathered dyers and weavers from all over Asia to satisfy the affluent desires of the court and ruling elite. This thousand year period proved to be a golden era in the history of Islamic decorative textiles, during which time the weavers at their encampment and village looms were influenced by court fashions and were beholden to the demands of suzerainty from their rulers ...

“ As the wealthy townspeople of the Islamic empires sought out the finest textiles and weavers both within their own lands and abroad, the villagers and nomads continued to weave the traditional knotted and flatwoven rugs and trappings that provided both the essentials and the comforts for their basic existence. These peoples, particularly the nomads, had little else but the natural environment to provide them with all the elements necessary for weaving. Harvesting the wool and hair from their animals, synthesizing the dyes from whatever source was available and building the coarsely hewn looms from bushes and trees, the villagers and nomads have produced an astonishing array of rugs and trappings over the centuries. Kilims served as rugs, and the flatweave process facilitated the production of strong and colourful bags to contain personal possessions, straps to tie bags to the animals during migration, bands to secure the tents when erected and large sacks for the transportation of food and clothing. Tent walls for the division of men’s and women’s areas were also often made from kilims.

“Kilims were used as door flaps, covers for food preparation, eating cloths and prayer rugs. Guests would be treated to a fine array of the best flatweaves as a display of their host's status and hospitatility; as the main room of a Muslim house contains little in the way of furniture, the host or guest would sit or recline on the floor, resting against a balisht floor cushion or rolls of bedding. In the summer months rugs would be spread outside in a shaded yard or on the flat roofs of the houses in the evening, to provide a comfortable refuge from the heat. Much the same arrangement exists in the tents of the nomads, who keep kilims neatly in bags both to save space and for ease of transportation. As well as providing comfort, kilims, together with jewelry, clothing, tent furnishings and animal trappings, expressed the identity of the village or nomadic group and served, along with knotted rugs, precious metals and animals, as a form of family wealth. At a time of crisis or of need for a commodity that can neither be made nor gathered, any of these possessions could be bartered or exchanged for currency to use in the markets of the local market town.

“Most importantly, the production of kilims has remained an integral part of a young woman’s, and her family’s opportunity to improve their standing through marriage, for not only does her weaving provide a useful source of wealth for her husband and his group, but it has also always formed a major part of the bride’s dowry ....."

Extracts from Brett & Fentress, 1996 “The Berbers”, (Blackwell Publishers)

“..... much of the material culture has been created by women or is used principally by them.” (p. 241)

“Weaving is the women’s activity which carries the greatest symbolic importance, signifying both the prosperity of a house whose flocks have produced sufficient wool to mount the loom, and the skill and application of the women in it ...” the loom is usually found in the most important room of the house ... “The dominance of the central room thus signifies the dominance of women within the household.”

Brett and Fentress, quoting others, go further by suggesting that the strict separation of male and female roles can bring about an autonomous female culture - compare Berber and Arab communities completion of education (p. 242-245).

The visitor to Morocco, familiar with Muslim ways, is struck by the social role of women in town and country ... in the town a woman might greet you by shaking hands, in the country the women labour alongside the men, in the villages they fill the social roles of their menfolk who have travelled in search of work ... Their kilims reflect this vigourous role in society, these are often bold statements of their extrovert personality, evidence of their confidence in the important economic, cultural and artistic role that their weaving provides them in society.

Again, this is not an interpretation which western preconceptions of Islam will find easy - there has been a huge emphasis upon the role of Islam in subjugating women and scarcely any mention of its liberating role.