Posted by David R. E. Hunt on 09-06-2003 09:54 PM:

Religion: Quintessential Expression of Intellectual Creativity

Salam Halikum-Thank you so much, Muhammad and Nasima, for you informative,

challenging, and provocative salon. I confess myself being nonplussed at the

assertion, as stated some time in the past here on Turkotek, something to the

equivalent of "although made by Islamic people, in Islamic regions of the world,

and during Islamic times, the kelim weavings of the middle east do not

constitute Islamic art". I for one hold that as a general rule "a rose is a rose

is a rose", a Venn diagram being no requisite in this case.

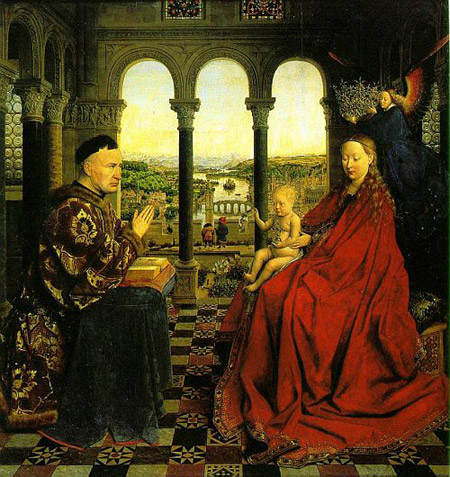

Art has always

been intimately associated with religion and belief systems, from the Cro-

magnon caves at Lascaux, to the Venus of Willendorf, on beyond to the votives of

Ur and this magnificent Madonna by Jan Van Eyck, by either representation or

symbolism.

I

think religion is the very essence of human creativity, an order from chaos,

inspired by the divine or otherwise, is the highest form of intellectual

creativity, and beyond any doubt, represent the greatest artistic, literary and

intellectual achievements of man. Without the requisite knowledge of

Christianity, the symbolic significance of those acts performed by the beings in

Van Eyck's Madonna are lost, and this magnificent work of art is greatly

diminished. Art is both a representational and intellectual process, and while

the analogy may not be perfect, the same is true of Islamic carpets.

Yella-

Dave

Posted by R. John Howe on 09-07-2003 08:05 AM:

Hi Dave -

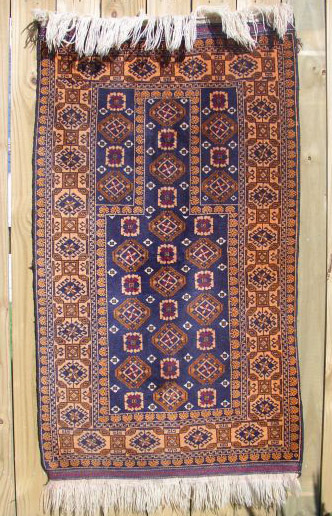

I take no particular issue with your notion that rugs and

textiles may be instances of "art," but many of us are entirely comfortable with

the alternative notion that they may only reach the level of "craft."

And

while lots of art is representational, lots of it is not. As I think you know,

there is an extensive and well-developed sector of Islamic art that is merely

geometric, without any intent to represent anything.

Regards,

R.

John Howe

Posted by Steve Price on 09-07-2003 08:09 AM:

Hi David

I think we tend to forget that "art for art's sake" is a

pretty recent invention. Nearly all forms of artistic expression were part of

religious or other practical considerations until, perhaps, 500 to 700 years

ago, and my guess is that if anybody took the time to generate the statistics on

it (after defining the term "art", of course), a substantial percentage still

is. And any attempt to understand a work of art without knowing something of the

cultural background of the creator will almost surely fail.

I was struck

by the star motif on the floor (or floor covering) in that painting. It should

ring lots of bells in the minds of ruggies.

Regards,

Steve

Price

Posted by R. John Howe on 09-07-2003 08:50 AM:

About the star on the floor:

It appears to be a mosaic and if this is

an Italian floor it might even be plausibly a Roman one. The sort of thing that

Islamic designers might later have picked up and "made their

own."

Regards,

R. John Howe

Posted by David R.E. Hunt on 09-07-2003 01:24 PM:

Commerce and the Silk Road

Dear John, Steve, and All- True, the tilework may be reminiscent of both

carprt designs and roman tiles, yet don't forget that so often the limitations

of the medium dictate design- I think of greater import to our discussion are

those fabrics composing the garments of the Chancellor and Madonna. Note

especially the floral device gracing the sleve of the chancellor's frock and the

border of Mariam's robe- Dave

P.S. Historically embarrasing comments have

been deleted by the author

Posted by Muhammad Thompson on 09-07-2003 03:21 PM:

wa alaikum assalam

Thank you for you contributions, Dave and others.

Understanding the process whereby we come to understand, appreciate and

value art - or, at least, think we do - is one of the reasons for writing such

articles. We note that muslims do not generally contribute to the discussion of

their own textile art and yet this ought to be an area where mutual

understanding (east/west, muslim/christian/jew) is possible ..........

difficult, yes, but possible nevertheless.

Without actually being a

muslim, how can you appreciate muslim art? If you are an unapologetic,

ethnocentric collector is their any point in trying to understand the art with

different eyes? You love it as a craft, as a token of a quite different society

which delights your eyes and senses by its qualities and associations; would it

be fruitful for you to understand better the religion from which it emerged? Is

it possible to understand sufficiently, short of becoming a muslim? If you live

in a society which considers religion to be only slightly more enlightened than

superstition, how realistic might such an undertaking be for you?

Not

easy questions but there are a number of reasons I think the answer to those

questions ought to be positive: the state of the world requires us all to

attempt mutual understanding; if you delight in the differences offered by a

society you ought to be as scientific as you can in understanding those

differences.

The actual situation leads us to think that the trade in

these rugs is founded upon misunderstandings: both sides are intent upon only

taking from the exchange what they value most. In another strand, Steve suggests

interviewing the weavers about the reasons for anomalies. We understand this

hypothesis about the reason for anomalies has been around for some time and yet

the simple tests have not been carried out. It really ought not be necessary for

us to pack a bag, catch a plane and pilot a questionnaire to put this hypothesis

to the test. We ought to be in the position where rug makers, sellers and buyers

are talking freely and openly. We do not seem to be in that position. Shouldn't

that change?

We sometimes get insights into art from unexpected sources.

I found Martin Ling's book on the Algerian Sufi, Shaykh Al Alawi, helped me

understand the religious life of north African muslim (men). There is obviously

a strong tradition amongst the men described here, of withdrawing from society

and contemplating. The women do not get the luxury of withdrawal but weavers

could be doing something equivalent. Our opinion is that the possibility of this

intellectual and religious activity amongst the women weavers, is not often

entertained by the rug literature. Perhaps this failure is as much the

responsibility of muslims and kilim manufacturers as the rug collectors.

But the most powerful insight comes from living with these textiles and

looking at them. Certainly, many are just rugs but the more time you spend with

some good pieces the more intriguing becomes the question, "Who was it that made

this? What was their purpose and their inspiration?"

Posted by Steve Price on 09-07-2003 08:21 PM:

Hi Muhammad

Your very thoughtful post summarizes nicely why I was so

enthusiastic about the prospect of your hosting a Salon. Turkotek is essentially

a community drawn together by an interest in an art form (and it's OK with me if

it's called a craft, not an art) that is predominantly Islamic. Yet, our

community includes very few contributors from the Islamic part of the world and

Nasima is only the third Muslim woman to ever appear on our boards (if my memory

is correct; even if my memory is incorrect, I'm sure it's a very small number).

Now, I understand, as I know you and Nasima do, that you don't speak for

all Muslims any more than I speak for all Americans. Islam, like any other major

religion, comes in many flavors. But all points of view contribute to our

understanding, and the Islamic have the potential of contributing more to it

than that of any others.

Regards,

Steve Price

Posted by Filiberto Boncompagni on 09-08-2003 05:25 AM:

Dear all,

About the van Eyck painting, I saw last year on a French TV

channel an excellent documentary on it.

The camera zoomed on the painting and

the commentator discussed the various ostensible aspects of elements and details

(which were remarkably "detailed" for a picture of 66X62 cm) and their possible

symbolic meanings.

I almost forgot the commentary - and the symbolic meanings

- but I still enjoy the artwork.

That makes me wonder…

1 - even if

you belong to the same culture that produced an artifact, this doesn’t mean

necessarily that you are much better equipped for enjoying and understanding it

than somebody else from a different culture.

2 - Art as we consider it

today is a universal language. It has different levels of meanings that are

cultural related and not always recoverable. OK, the more one understands those

levels the more he can appreciate the whole, but there is always a universal

"upper" level that can be understood by everybody. That’s why, I guess, it’s

called Art.

No polemics here, just food for thought.

About the

"Roman" floor…

Even if the painting appears to be of a real space and place,

the composition is "fictional" - or at least this is what my book says - and I

think I remember from the TV documentary.

The architecture of the room is

Romanic with Gothic elements and the landscape is inspired by the Flanders

region.

Curiously, the same book says on the Islamic Art: "One can say

that Islam did not inspire a religious art - but only an art that risked to be

unreligious."

Not willing to re-read the book,  it seems to me that this provocative

sentence is given

it seems to me that this provocative

sentence is given

by the fact that - in contrast with preexisting cultures -

Islam prohibited (almost, there are always exceptions) the representations of

living beings. This limited the use of visual arts such as painting, mosaic and

sculpture and gave prominence to architecture.

What is peculiar of

Islamic Visual art, though, was the way it developed a new treatment of

Architectural surfaces: carving, or painted ceramic tiles, with highly geometric

decorations, sinuous/floral decorations (the Arabesque) and the use of

Calligraphy for decorative purposes. This "new look" was also used not ONLY for

architecture but also for objects of everyday use, like pottery, ceramics,

furniture, textiles and metalwork. This imparted also a distinctive ABSTRACT

character to Islamic Art.

Regards,

Filiberto

Posted by Filiberto Boncompagni on 09-08-2003 05:48 AM:

What I wrote above doesn’t mean that I disagree with the need to "us all to

attempt mutual understanding", on the contrary!

Posted by David R.E. Hunt on 09-14-2003 07:07 AM:

Perspective

Filberto,Muhammed, and All-

Perception is selective and learned. Take a

Pigmy from a congo to the plains, and he will exclaim at the minature Wildebeast

before him- he lacks the ability to interpret depth at this range. Infants of a

certain age have no depth perception, and those few blind who have their vision

restored, at first find the visual data incomprehensible. Rods,cones, cranial

nerve and cerebral cortex all, we are hard wired for perception, but the

interpretation of data is selective and learned. As such are religous symbolism

in art

Aside from a most general introduction to the work and it's

celebration as a masterpiece in the study

of perspective, I've not been

exposed to a critical analysis of Van Eyck's Madonna, and hence

must

formulate my own opinion of it's content.

Superficially, it could

represent nothing more than mother and son visiting a patrician husband

and

father at the office, but the Chancellor's garb, that jewel encrusted

Faberge rattle clutching babe, possessed of the contenance of a sixty year old,

to say nothing of the gesticlating right hand and eccleastical crown conveying

cherub hovering over Mary's head ,say otherwise.

It would seem that the

Chancellor, in recognition of his piety and good works on behalf of the church

or community, is personally recieving a visit from the holiest of holy's and the

Virgin. This painting is rich with religous symbolism, some quite obvious and

some more subtle, but I think it fair to say that much of the symbolic import

would be lost upon someone without considerable knowledge of

Christianity.

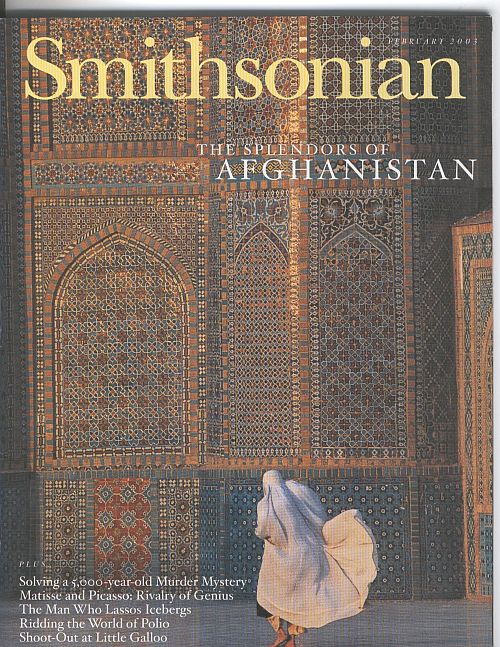

The symbolic content of Islamic art is notable not so much for

it's content as for it's omission.

The prohibition of representative art has

resulted in the development and variation of geometric design and use of color

being refined to a high level, especially in textile and ornamental tile

work.

While some criticism to the effect of Islamic art being mere

ornamentation may be in order,at least from the western perspective of what

constitutes art, I believe that the overall affect of the package, if you will,

with the hypnotically patterned tiles,the rich and varied colors, the

embellishment of portals, in combination with an arry of carpets presents a

kalaeidoscopic, almost hallucinogenic and visually stunning experience. The

gothic cathedral, for all it's graceful arches, proportions, and the flying

buttress, is puritanically bland in comparison to the riotous colors of the

mosque, with it's tiled dome,stalactite ceiling, and everywhere the glitter of

gold. Heaven on Earth. - Dave

Posted by Vincent Keers on 09-15-2003 11:32 AM:

Dear religious maniacs,

Most religious "art" is made to please the

crowd. Whatever "Sold" the religion, was made. So, to think, religion created

Art is shortsighted. 99% of the crowd couldn't read or write. So religion needed

cartoons. Religion oppressed the Artist.

I don't like The Madonna by Jan van

Eyck.

It's a constructed caboodle to please the crowd of those days.

If

you forget all the Christian stuff, it's a mediocre painting. But, van Eyck had

to eat.

(Alltough I like the velvety mantle as craft)

So, religion is

a disturbing vibration that disturbes an honest judgement of art.

It's

pathetic that people are allowed to tell the atheist, like me, they do not

understand

bla, bla bla, bla,

bla.

..............................................................

..............................................................

..............................................................

..............................................................

Best

regards,

Vincent

Posted by Steve Price on 09-15-2003 01:19 PM:

Hi Vincent

You wrote, Most religious "art" is made to please the

crowd.

True, but the same is true for most other art as well. Van Eyck

isn't the only artist that had to eat. Religion didn't create art, but it did

(does) provide outlet for artistic expression, often very deeply felt.

I'm puzzled - how do you see religion as disturbing honest judgments of

art? To take the van Eyck painting as an example, whether it is great art is

unimportant in the context of our discussion, but knowing something about

Christianity is essential to understanding the artist's message in it. That is,

religion not only provided the outlet for van Eyck's artistic effort, it

provided the inspiration and is crucial to understanding the painting.

I

don't think anyone has forced anything on atheists. You and I and everyone else

here are perfectly free to believe in no God, one God, or many Gods. We are free

to assign whatever attributes make sense to us to the God (or Gods) in which we

believe if we have such a belief. I'm sure your understanding of the van Eyck

would diminish if your atheism were accompanied by ignorance of Christianity; it

looks to me like your knowledge of Christianity has a great deal to do with your

reaction to the painting.

I think it's important to separate the

questions of whether you must be a Christian to understand the painting, and

whether you must know something about Christianity to understand the painting.

They are related, but not the same thing.

I don't think you have to be a

Muslim to understand the work of Muslim artisans, but it helps a lot to know

something about the culture and traditions of the creator of a work and, if

he/she was Muslim, that was probably a pretty important element in his culture

and tradition. Do you disagree?

Regards,

Steve Price

Posted by Vincent Keers on 09-15-2003 07:55 PM:

Hi Steve,

No, most Art isn't made to please the crowd. It is made,

created and maybe the message is picked up. If so, the artist is a famous

artist. If not, the artist is an artist.

Religion, or whatever glorious

supernatural fairytail that gets the crowd in one direction, corrupts the

artist. And if not, inquisition will.

quote:

it looks to me like your knowledge of Christianity has a great deal to do with

your reaction to the painting.

Yes.

quote:

I don't think you have to be a Muslim to understand the work of Muslim

artisans, but it helps a lot to know something about the culture and

traditions of the creator of a work and, if he/she was Muslim, that was

probably a pretty important element in his culture and tradition.

Yes, I agree. But if this gathering of "wisdom" only sheds a

light on one side of the story, it fails to do so.

What I miss is some kind

of contemplation.

And I miss Nasima.

Best regards,

Vincent

Posted by Steve Price on 09-15-2003 08:48 PM:

Hi Vincent

I don't have any hard data on the subject, but if an artist

has to eat, he has to generate work that appeals to buyers. After he becomes

famous, people will come to him under his terms. I suspect that the percentage

of artists who achieve that stature is pretty small.

Nearly all African

tribal art was made to meet the needs of religious ritual except for that made

for prestige display or sale to tourists. In that case, the corrupting influence

was separation from the religious objective. Tribal textiles Asia have strong

religious roots in their iconography, and we generally think of the weavers'

loss of the meaning of those roots as degeneration.

Do you think the art

in European cathedrals or the works of Michaelangelo would have been created in

the absence of church patronage? I don't. Inquisition hasn't been a pressure on

anyone for centuries - why raise it as a significant factor in the way artists

work?

To shorten a long story, I don't understand your contention that

religion corrupts the artist. In fact, it appears to me that until fairly

recently (say, the past 600 years or so), most art - good, bad or indifferent -

was made for religion-related use, and a significant percentage still is.

Can you be more specific in arguing your side of this? Just announcing

it as something you consider to be true is not terribly compelling, but maybe

you've thought of some relevant things that I

haven't.

Regards,

Steve Price

Posted by Tim Adam on 09-16-2003 08:32 AM:

Hi Steve and Vincent,

I think there are two sides to the Christian

church's involvement in the arts. On the one side the church spent (other

peoples') money on commissioning art work. Because of this a lot of art was

produced - not only paintings and sculptures, but music too! - that might never

have been produced otherwise. And this is to the great benefit of our

generation, because we did not have to pay for it.

The other side is that

the church, as most commissioners of art I guess, had a very clear idea about

what they wanted to get done. The church determined the motive, and only the

execution was left to the 'artist'. So, the artist was not an artist in the

modern sense. He was more like a laborer (Handwerker). In order to survive, he

had to do what the church told him to do, whether he liked it or

not.

Take the Van Eyck painting for example. Absolutely fantastic in

terms of execution. And the motive? A man kneeling in front of a beautiful woman

with an ugly child on her lap. The woman looks at the child, the child looks at

the man, and the man looks at the woman. What a ridiculous scene. But the

execution is so perfect that we can easily overlook the motive and still call it

art.

To the extent that the church forces an artist to do something that

he or she would otherwise not do, I think it is fair to say that the church

corrupts the artist. The church stifles the artist's creativity. This is bad for

everybody except for the church. Think about the great paintings Van Eyck could

have produced, had he not been forced to waste his time with ridiculous

Christian motives!

And what does all this have to do with

rugs?

Tim

Posted by Steve Price on 09-16-2003 10:52 AM:

Hi Tim

Let's start with what any of this has to do with rugs. The

topic for the month opened as western misunderstanding of Islamic art (yes, I

paraphrased it, but I think the meaning is the same as in the original). So the

relationship of religion to art was there from the start.

You are

correct, of course, that the role of the church (like the role of any other

patron) in the art it supported has elements of a mixed blessing. I don't know

the history of van Eyck's relation to the church, but I assume that he was

commissioned to do the painting rather than forced to do so at knifepoint. The

artists I know are happy to take commissions within certain limits, so I suspect

that the limits put upon him by the commission were acceptable to him. Maybe not

- someone who knows the history might be able to clarify this.

Unless the

church gave him money that they stole or embezzled, it wasn't "other peoples'

money". Once someone gave it to them, it was theirs. Everyone working in the

public sector is paid with "other peoples' money", some of it given grudgingly

and under threat of imprisonment for failure to do so.

You say, To

the extent that the church forces an artist to do something that he or she would

otherwise not do, I think it is fair to say that the church corrupts the

artist. I think this position is unassailable. We could also say, to the

extent that the church makes it possible for the artist to do what he or she

could otherwise not do, the church supports art. There are, as you point out,

two edges to this sword. Could van Eyck have produced a corpus of outstanding

art in the absence of church support? We'll probably never know.

I also

think it would be considerate to many of our readers if we avoid attaching

adjectives like "ridiculous" to their deepest beliefs; the word struck me as

unnecessary to the argument anyway.

Finally, I point out that many

collectors value central and western Asian arts, especially the tribal arts and

crafts, largely because of the religious and cultural content. Just as we can

conjecture about what van Eyck might have done if he wasn't part of a particular

Christian group, we might wonder what some Salor woman might have done with her

talent if it wasn't constrained by the limits imposed by her culture and

religion. We might, but to what end?

Regards,

Steve Price

Posted by Vincent Keers on 09-16-2003 11:53 AM:

Hi Steve,

The distinction between applied art and art.

I say:

Religious art is applied art.

Culture and habits created religion.

So we

can study the culture and habits in a certain society and the religion it

constructed. But I do not have to study the religion. What I do want to

investigate is: What result that manufactured religion had on the people in that

specific culture. Negative and positive.

quote:

Do you think the art in European cathedrals or the works of Michaelangelo

would have been created in the absence of church patronage?

Maybe better? But the Church was where the money was.

quote:

Inquisition hasn't been a pressure on anyone for centuries - why raise it as a

significant factor in the way artists work?

Try to write a book about the culture that manufactured modern

Islam.

quote:

(say, the past 600 years or so), most art - good, bad or indifferent - was

made for religion-related use, and a significant percentage still is.

Yes. So it is applied art.

And this is 2003. So why do I

have to study Islam in a way it is presented by our host? I'm happy I survived

my Christian upbringing.

And because religion is false, how can it create

beauty? Art=Creation of beauty.

Michaelangelo created beauty. Religion

didn't. Did he create religious beauty?

Maybe he did and maybe he

didn't.

I don't know. Do I have to know?

Time out........

Best

regards,

Vincent

Posted by Steve Price on 09-16-2003 12:28 PM:

Hi Vincent

I agree that religious art is a form of applied art. So is

nearly all textile art (at least, textiles within the usual range of interest to

most of our readers), but I've not heard it disparaged for that

reason.

Your definition of art (creation of beauty) is only one of many

definitions, and probably not the one that would rise to the top of most

peoples' lists. Is Munck's "Silent Scream" beautiful? Is it art? How about

Picasso's "Guernica"?

You are under no obligation to study Islam in the

way our hosts presented it, or to agree with anything they say (or with anything

I say!). We aren't obliged to accept their point of view, although I do feel

obliged to treat it (and them) with respect.

Regards

Steve

Price

Posted by Filiberto Boncompagni on 09-16-2003 12:58 PM:

Hey Vincent,

Did you really mean "Culture and habits created

religion".

I thought it was

the other way around.

And what about Zoroaster, Buddha, Jesus and Mohammed?

Regards,

Filiberto

Posted by Sue Zimmerman on 09-16-2003 03:11 PM:

Hi Steve,

As an artist I don't think you have any idea of how

offensive you take on artists strikes me. With a little shuffling around, what

follows may be the only way I can show you what you sound like to me. Bear with

me, please. You have gone out of your way to defend others from what you believe

to be assaults on their deeply held beliefs. I would like the opportunity to

defend mine from you. Please do not quote me out of context as the following is

only for demonstration purposes.

I have no hard data on it but even

priests have to eat. Many believe there is an active religious inquisition

pressuring people right now -- a corrupting influence separating pure religion

from religion for profit. This religion has lost its roots and its work appears

degenerate. All can see what it has done to the food chain, the soil, the water,

and the air. None can flee. This religion, the most powerful one of our

civilization, is science. As the rock band the Who sang, "Meet the old boss,

same as the old boss". Sue

Posted by Steve Price on 09-16-2003 03:25 PM:

Hi Sue

I had no intention of offending you (or any other artist), and

would like to correct whatever I said if it was, indeed, wrong, or to apologize

publicly if it was thoughtlessly worded.

I've read your message several

times, and can't figure out what you're trying to say beyond the fact that you

are offended by something I wrote and clearly consider "science" to be the

source of some serious problems. Can I ask you to be more

direct?

Thanks,

Steve Price

Posted by Sue Zimmerman on 09-16-2003 04:18 PM:

Typo correction, sorry, the Who sang "Meet the new boss, same as the old

boss". Sue

Posted by Steve Price on 09-16-2003 04:59 PM:

Hi Sue

Forgive my density, but I still don't get the point of the post

you just corrected. Please be very direct about what you have to

say.

Thanks

Steve Price

Posted by Sue Zimmeman on 09-16-2003 05:19 PM:

Hi Steve,

I don't know how to be more direct. I don't ever know what

you are reading that I have written. I say "people" you say I say "tribeswomen".

I say "court" you say you guess I mean "urban centers" . I say to be

ethnocentric is absurd you say I am ethnocentric and imply I believe history and

science was invented in the West. These are just off the top of my head things

from the last day or two. Now this. I don't know what I can do to make sure

whatever else I say is not misunderstood by you, not that I'm blaming you for

this, but I don't have the strength left to define every single word I say or

look up and rewrite in quotes what I'm referring to in this thread, which is

pretty much everything you have said about artists. Unless some trouble shooter

comes to my aid I guess you are going to have to remain puzzled. I don't think

you will mind that too much anyway. Maybe I'm wrong. Sue

Posted by Steve Price on 09-16-2003 05:57 PM:

Hi Sue

I'm trying to stay with you on this. Let's start

here:

[QUOTE]Originally posted by Sue Zimmeman

I say "people"

you say I say "tribeswomen". I say "court" you say you guess I mean "urban

centers".

Just to keep it in front of us, here's the text (yours)

from which I made those leaps: Odd bedfellows? Do you feel the same way about

the weavings made by court trained "tribal/nomadic" people who have left court

to resume weaving back home when their work is exhibited alongside the weavings

of those who never left? My presumption, based on the general focus of what

gets discussed on this site, is that the tribal/nomadic people to whom you refer

were western or central Asian. You explicitly state that they were weavers in

their tribal community. That makes them women, although I frankly don't

understand why it's offensive for me to call them that. Can you expand a little

on this? You say that they were court trained, but, after being court trained,

left court to resume weaving back home. If "court" isn't some urban center, what

or where is it? Again, can you explain why you are offended as an artist by my

guessing that 'court" is urban (as opposed to nomadic)? Is it complete

insensitivity on my part to be unable to see the offense in that? Give me the

benefit of assuming that it is ignorance, and educate me on

this.

Originally posted by Sue Zimmeman

I say to be

ethnocentric is absurd you say I am ethnocentric and imply I believe history and

science was invented in the West. I don't recall saying any of that, nor did

I find it when I looked. The closest thing to it that I could find was my

response to this statement of yours in another thread:

To be ethnocentric,

if history and science are to be believed at all, is absurd.

Here's what

appears to be the section of my response to which you refer:

I happen to

come from more or less the same culture as you do, so I think history and

science are pretty useful things to know. But there are cultures that reject

science (religious fundamentalists, for instance) and history has many versions

(ask any feminist). That is to say, your statement is ethnocentric - it implies

that our culture is superior to some others by the value it places on history

and science.

Notice, please, that I did not say or imply that history or

science were invented in the west. I said that our culture values them, which is

reflected in your own statement (citing science and history as the evidence for

what you were saying). I pointed out that this is not universal for all

cultures, and that citing science and history as convincing evidence is a

roundabout way of expressing confidence in the superiority (at least in this

respect) of ours to theirs. I specifically mentioned one group that rejects

science and another that takes a jaded view of what we call history.

And, once again, would you tell me how this offends you as an artist?

And, can you be more specific about what elements of "just about everything I've

said about artists" in this thread are offensive to you, as an artist?

Thanks,

Steve Price

Posted by Vincent Keers on 09-16-2003 08:12 PM:

Hi Filiberto,

Do you really think religion created culture?

Without

religion, no culture?

Hi Steve,

Now you do it again.

Comparing

art and applied art. Like our hosts do.

quote:

The topic for the month opened as western misunderstanding of Islamic art

I do not think the western world (in general) misunderstands

Islamic art. It is less appreciated in the western world like most applied art

is less appreciated in the western world.

But, people that claim they are

unique in understanding Islamic applied art, do not understand the real western

society and its Art. They see Mac Donalds, Coca Cola, Levi's, Mercedes, A soup

can etc.

Think that's what I say.

So, why didn't I?

Maybe because it

doesn't feel right to say this.

Time out.....

Best

regards,

Vincent

ps. Silent scream. Beautiful ugly.

Beautiful war.

Yes, i think that's beautiful Art. Don't you?

Posted by Tim Adam on 09-16-2003 08:25 PM:

Apologies if I offended anybody with my description of the Van Eyck painting.

You are right, Steve, the

word 'ridiculous' wasn't really necessary. I'll try to choose my words more

carefully next time.

You are right, Steve, the

word 'ridiculous' wasn't really necessary. I'll try to choose my words more

carefully next time.

Art could not survive without its sponsors, and the

church has been one of the greatest sponsors of course. Even though this sounds

pretty positive, it's not all that rosy. First, the church used its power to

tell people what to do (think) and what not to do (think). This applied to

artists as well as to everybody else. Imagine Van Eyck had painted the pope as

he is seduced by the devil. Unthinkable. This problem has passed in the

meantime, because the church no longer wields the powers it once

had.

Second, to create art works of monumental proportions a lot of money

had to be amassed. Think about the wealth necessary to build the palaces and

cathedrals in Europe, the pyramids, the Taj Mahal, the Ardabil carpet, that we

admire nowadays so much. Where did this wealth come from? Did the people give it

freely? Did the masses not mind living in poverty so that the church and others

could build themselves palaces? I don't think so.

It's a big dilemma that

the greatest pieces of art can usually only be afforded/commissioned by a small

elite, and that the elite usually gets its wealth from the masses. There are

exceptions, but I think those are rare. Without expropriation there would be

much less art around.

Tim

Posted by Steve Price on 09-16-2003 09:09 PM:

Hi Vincent

I guess I consider "applied art" to be legitimate art. If

it isn't, then utilitarian textiles can't be art either, and I think the best of

them are.

Your opinion is that the western world, in general, does

understand Islamic art. Muhammad and Nasima clearly think differently about

that, as evidenced by the title of their Salon. Is difference of opinion a bad

thing to have crop up in a discussion forum? I don't think so. I think it's

healthy, ultimately educational, and sharpens all of our thinking.

I

wouldn't call "Silent Scream" or "Guernica" beautiful, at least not in the

conventional sense of the word. I do think they are great art. The phrases,

"beautiful ugly" and "beautiful war" are oxymorons. They make no more sense to

me than, say, "illiterate literate" or "gentle violence".

Regards,

Steve Price

Posted by Sue Zimerman on 09-17-2003 12:32 AM:

Hi Steve,

It might be too big a leap to assume that tribal weavers

were always woman no matter how many times it is said by however many people. I

have no problem with you calling women women. I mind that you imply that I agree

with you that tribal weavers were always women. That gives the impression that

the weavers I was referring to were women. The likelihood of tribal women going

off to court to weave seems more unlikely, to me, than men weaving. But more

important than my minding your misunderstanding of what I say is it's

significance as an example of how assumptions can lead to totally erroneous

translations even between people of similar cultures, when one assumes too much.

Transcultural mistakes of this nature can have dire consequences, if you care to

think about it.

I have not said that you implied that history or science

was invented in the West. I do not think the East values history or science any

less than the West does. All cultures are a mixed bag. I don't believe I was

saying in a round about way that our culture is superior to theirs.

The

history I was thinking of was both ours and theirs. The US is not the first

"melting pot". I can give tribal and other cultural examples if you don't know

about them -- bona fide primary source examples.

The science I was

thinking of is not western or eastern either. No matter which part of the

scientific elephant is touched by our blind fingers, the genetic, the

linguistic, the structural, the leitmotif of it's systemic organization, etc.,

one thing is innately clear, we are related to each other. Ethnocentricity is

absurd. It is unbefitting a custodial species. Rise above it.

Craftsmen

carry on traditions. Artists, unwittingly, are the founders of traditions while

they are on their way to something else. If you can understand this you can

understand why I feel offended. If you can't, let's drop the subject and move

on. Sue

Posted by Filiberto Boncompagni on 09-17-2003 02:04 AM:

Hi Vincent,

Do I really think "religion created culture?

Without

religion, no culture?"

Well, considering that religion is one of the first manifestations of

culture, historically speaking, yes.

Try to think about Ancient Egypt.

Remove religion from their culture.

No pyramids, no Sphinx, no Karnak temple,

no Valley of the Kings and related mummies - just to name a few examples - all

forms of art/culture correlated with religion.

And, by the same logic,

what about Athens without the Parthenon? And so on, one can go like this for

every culture.

But you did not answer to my question:

If religion is

created by culture and habits, what about Zoroaster, Buddha, Jesus and Mohammed?

I can throw in also Abraham, Confucius and - why not? - S. Paul, Martin Luther

and Calvin. All men that either CREATED religions or had a huge impact on

them.

Best regards,

Filiberto

Posted by Stephen Louw on 09-17-2003 05:00 AM:

Sue --

I am not sure if I understand what you are trying to say in

your various posts, or the reasons for your dispute with Steve. Howevor, I think

it is fair comment to suggest that weavers were mostly women: designers, dye

masters, etc. predominantly men. And it is fair comment to suggest that whilst

the court probably did interact with and help support male designers and male

heads of weaving workshops, the weavers in these workshops were woman. That was

certainly the case with Akhbar (see Daniel Walker's Flowers Underfoot). Also,

see Leonard Helfgott's splendid sociological study of so-called "tribal" weaving

in 19th century Persia, Ties That Bind.

Stephen

Posted by Vincent Keers on 09-17-2003 09:22 AM:

Hi Filiberto,

Egypt?

First there was the Nile.

So people

gathered.

This gathering had 1 binding factor.

Food production. This is

culture. People had to work together, specialize etc.

When all bellies where

filled, the first binding factor gets less. So they gathered the production and

stored it. This created a central power. How could this centralized power

survive when the harvest was less? By making this power supreme. God on

earth.

This worked ok but had one minor point. A god on earth gets killed

sometimes. So this created instability.

Some people learn. So next time God

stays out of harms way and sends only messengers.

In the end you said it

yourself. All those men "created" religions.

The most beautiful example is

Buddha.

His culture was one big feast within a culture of poverty. Without

this setting, no Buddha. No religion.

Best regards,

Vincent

Posted by Filiberto Boncompagni on 09-17-2003 09:54 AM:

If you say

so...

If you say

so...

Buddhistically

Filiberto

Posted by Vincent Keers on 09-17-2003 11:33 AM:

quote:

But you did not answer to my question:

Well, I gave it a try.

So I was only trying to be

civilized.

Something wrong with that?

Best regards,

Vincent

Posted by Filiberto Boncompagni on 09-17-2003 12:08 PM:

Something wrong?

Absolutely not!

Where did you get that

impression?

Filiberto

Posted by Vincent Keers on 09-17-2003 01:33 PM:

Hi Filiberto,

ok.

I'm wrong.

Sorry.

Best

regards,

Vincent

Posted by Filiberto Boncompagni on 09-17-2003 02:06 PM:

OK Vincent,

I forgive you.

This time.

Best

Regards,

Filiberto

Posted by Vincent Keers on 09-17-2003 08:53 PM:

You make me  ,

Filiberto.

,

Filiberto.

By the way. Because we are having this very deep discussion,

about culture, religion, Islamic art etc. and I sincerely appriciate your

contribution and because you seem to belong to the incrowd, can you tell me

where Nasima is? I've read some lines from Mohamad, but he's the male, I

think.

Doesn't Nasima have a line or two.

If not...why use her

name?

Think it was Steve that said: Maybe we can learn something by

discussing what they think and what others think.

I'll try to tell what I've

learned so far:

This salon clearly underlines the basic western idea that

woman, under Islamic rule, can't speak for themselves.

Some other frustrating

things.

Next salon should be:

Clitoris and how it is misunderstood in

the Islamic world. I will be the host and a few girls. But I will do most of the

talking!

And quote some Happy Hooker pages.

Best

regards,

Vincent

Posted by Steve Price on 09-17-2003 09:14 PM:

Hi Vincent

Muhammad and Nasima are in London, near enough for you to

visit them. I'm pretty sure London is not under Islamic rule. I believe they are

husband and wife, but I'm not certain of that; they are definitely business

partners.

Her name appears on the Salon essay, so I assume that she

co-authored it. I attach no significance to the fact that the posts come under

Muhammad's name, and your presumption that it means that she is subservient

could be off by a mile. She may dictate the text to him for posting, for all you

or I know.

Regards,

Steve Price

Posted by Filiberto Boncompagni on 09-18-2003 01:30 AM:

Well Vincent,

I must admit that I share your thoughts about Nasima.

Regards,

Filiberto

Posted by Filiberto Boncompagni on 09-18-2003 08:44 AM:

Dear all,

I followed the discussion on this thread rather

distractedly, but re-reading it I think I should post some more comments,

especially now that that spirits had calmed down.

About church and

artists:

Van Eyck’s painting is titled "The Virgin of Chancellor Rolin":

it was likely to be a work commissioned by the Chancellor rather than by the

church.

A quick search:

http://www.kfki.hu/~arthp/html/e/eyck_van/jan/index.html

confirmed

that Nicolas Rolin, Chancellor of Burgundy and Brabant commissioned it. So, this

is a portrait, not a work for a church.

Jan van Eyck was recorded in 1422

as the varlet de chambre et peintre ("honorary equerry and painter") of

John of Bavaria, count of Holland.. In 1425

he was summoned to Lille to serve

Philip the Good, duke of Burgundy, the most powerful ruler and foremost patron

of the arts in Flanders. Jan became a close member of the duke's court and

undertook several secret missions for him. He remained in the duke's employ

until his death.

Jan was famous for having perfected the newly developed

technique of oil painting. His naturalistic panel paintings, mostly portraits

and religious subjects, made extensive use of disguised religious

symbols.

In relation with this last point, I don’t think that he was

"oppressed" by the church.

Like any other artists, ancient and modern,

specialized in portraits, he painted what he was asked to paint by his clients.

And when the church commissioned him some work with religious subjects, he was

happy to oblige. I think that his position at the Duke’s court made him quite

free from any obligations to the church. May I also suggest that he believed in

what he painted?

Tim Adam wrote:

"The church determined the

motive, and only the execution was left to the 'artist'. So, the artist was not

an artist in the modern sense. He was more like a laborer (Handwerker). In order

to survive, he had to do what the church told him to do, whether he liked it or

not."

Do I risk a tautology if I say that artists in modern sense exist

only since modern time?

Before that the artists were considered nothing else

than "deluxe" artisans. They didn’t make paintings - or sculptures - on their

own in the hope to sell them later but they worked on commission and they found

perfectly normal to paint what they were asked.

Again, the modern Artist

(with capital A) is a recent invention of our western culture. I’m not aware of

how the artists were considered under different cultures (say, Indian, Chinese,

Japanese) but I rather guess that it was no much different by our view in old

times, i.e. like artisans. They probably had to work on commission too and do

what the customer (secular or religious) required.

Best

regards,

Filiberto

Posted by Tim Adam on 09-18-2003 08:05 PM:

Dear Filiberto,

I think in other cultures artists were also considered

artisans. For example, in China there was the imperial workshop. Only the best

of the best would be admitted to this workshop. Imperial artisans were quite

privileged I think. The same probably applies to Van Eyck and others the Church

dealt with. But I think there were also lots of other artisans/commissioners of

art, that did not comply with the church's way of thinking. Those people didn't

live as long as others. The church did not tolerate creativity that was outside

its dogma.

Although the church was a great sponsor of some

artists/artisans, I think it had a devastating effect on others. This is why I

have a hard time accepting that the church had an overall positive affect on the

arts.

Regards,

Tim

Posted by Steve Price on 09-18-2003 09:13 PM:

Hi Tim

I think we can take it as a given that there would have been

some dominant religion, and that religion would have had profound influence on

the people, including the artists. I'm unaware of any culture on the planet that

didn't have religion - even the officially atheistic USSR substituted an

ideology for more traditional theology, but in a real sense, that was a

religion, too.

The question is whether, on balance, the church

(and we're talking Medieval Europe, so it must be the Roman Catholic church) was

good or bad for art and artists. I think the question needs to be framed within

the context of the possible alternatives. Would some other religious framework

(within the range of those that were possible in Europe at the time - no fair

using, say, Unitarianism as an alternative) have been better or worse? I don't

know the answer, by the way.

Regards,

Steve Price

Posted by Filiberto Boncompagni on 09-19-2003 04:09 AM:

Dear Tim,

I have the impression you have an axe to grind with the

Church and now I find myself in the uncomfortable position to defend her (it?).

I say uncomfortable

because I am agnostic and anticlerical, you know…

Let’s try to repeat what Steve

wrote above but with different words:

You say "But I think there were

also lots of other artisans/commissioners of art, that did not comply with the

church's way of thinking. Those people didn't live as long as others. The church

did not tolerate creativity that was outside its dogma."

I do not think that

free thinkers were the norm, in the past. They are a rather recent phenomenon,

like the "Modern Artists".

In the past artists conformed to the current

ideology just like anybody else. ("Current ideology" being the religion of

Ancient Egypt, Buddhism, Greco-Roman paganism, Christianity, whatever.)

So,

they most likely were believers and they worked inside the frame of that

believing.

Consequently I ‘m reluctant to think that the Church starved

rebellious artist while it promoted more conformist ones - because they weren’t

rebellious artists!

Anyway, I don’t think it was worse than other religious

powers in other times and other countries.

And, uh, I guess that the

Imperial Artisans in China had artistic rules to follow as well…

Best

regards,

Filiberto

Posted by Stephen Louw on 09-19-2003 04:14 AM:

Steve

My (avowedly atheist) view is that history tells us very clearly

that the Church, or any form of state patronage, is bad for art. At the least,

its bad for an art form deemed to be expressive and interpretive, as opposed to,

simply, an art form that reflects dominant symbolic systems, ideas,

etc.

But it’s not religion per se, but, rather, the way in which it helps

structure thought and actions. Think of Weber's study of religion and modernity:

the Protestant ethic is seen as inherently innovative, in that it pitted the

lone individual against a hostile world, and compelled the individual to seek to

master and transform that world so as to overcome evil. In Weber, this is seen

as supportive of a particular type of capitalism, but it feeds equally into his

studies of music and other art forms.

In my view, the question is the

relationship between different religions and the state. In, especially, the

Calvinist strand of Christianity, the individual is not only allowed to but

encouraged to develop herself as a creative entity, independently of state

power. In other religious orders, Islam in this case, no distinction is or can

be made between the world of the personal and the world of the political: the

Caliphate implies an integration of both, and those not living in the Caliphate

are compelled to struggle for such an integration.

Of course, the real

world, the world in which our weavers lived, was seldom the world of High Islam,

but, rather, a world in which local spirit and animist beliefs existed side by

side with (often non-literate) variations of Islam. Thus the multiple influences

in much of the so-called "tribal" carpet genre we love so much.

Just a

few thoughts

Stephen

__________________

Stephen

Louw

Posted by Filiberto Boncompagni on 09-19-2003 05:51 AM:

Hi Stephen,

Glad you included state patronage with Church. I suggest

we substitute both terms with "power patronage" - power meaning religious,

political or financial.

Again, when you say that any form of Church or state

patronage is bad for art, you reason in term of Modern Art, where the Modern

Artist is allowed TOTAL freedom and creativity.

- Note: True,

Protestantism encouraged this kind of individualism - which was already there

thanks to the Renaissance. Think to Michelangelo, already a modern Artist - with

a big "A": big enough to defy the Catholic Church and impose the representation

of NUDE bodies on the Sistine Chapel ceiling. (Admittedly, most of the nudity

was covered with new painting after Michelangelo’s death, but now after the

restoration one can see it again.)

Now, is power patronage bad for

art?

Excluding primitive and tribal culture, most of Art on this planet

WAS and still IS (think to modern architecture) due to power patronage.

Open

a book of World History of Art…

So, what do we do, we dismiss Ninive and

Persepolis sculptures, Tutankhamon’s treasure, Aztec buildings, the Angkor Vat,

Michelangelo’s "Last Judgement" as a lesser art because they were

commissioned?

Best regards,

Filiberto

Posted by Tim Adam on 09-19-2003 08:17 AM:

Dear Filiberto,

Earlier on it was mentioned that religion is the

highest form of creativity and represents the greatest artistic achievement of

man. I could not disagree more with such a statement. In my view religion tries

to impose a particular set of beliefs and behavior upon people. It offers a

usually quite rigid framework, and does not allow people to deviate from that or

question it. If they do, they get into trouble. This is why I think religion and

creativity are really at opposite ends of a spectrum. Creativity causes change.

Religion tries to preserve a status-quo.

There are, of course, a lot of

creative people within the church who demand change. But I feel the church tries

very hard to prevent that from happening. Sometimes it (she?) fails and change

does take place, but sometimes she is successful. Then certain fractions within

the church break away and form their own church.

What you wrote about the

Sistine Chapel ceiling is a great example. The church was weak relative to

Michelangelo at the time, but when he was gone they could again do, as they

deemed best.

The biggest plus of the church’s involvement in the arts

that I can see is that the church has spent a lot of money on it. And I would

not go so far and say that commissioned art is necessarily less worthy because

it was commissioned. Otherwise, the church’s impact was probably more negative

than positive, at least during the Middle Ages. Now the Church is more benign,

of course.

Anyhow, let's talk about rugs!

Regards,

Tim

Posted by Stephen Louw on 09-19-2003 12:10 PM:

Hi Filiberto

I think you slightly misunderstand me -- I am speaking of

art that seeks critically to interpret the social universe, as oppose to art

that seeks faithfully to reproduce a defined aesthetic or religio-political

order. Much of what might be (following Gellner) described as High Islamic art

would fall into the latter.

I suspect that art develops in periods or

contexts when it engages with a critical order. And I am also of the view that

most if not all religious orders inhibit the capacity of people to engage in

critical reflection. This is particularly the case in secular resistant

faiths.

Thus I disagree with your comment that "Excluding primitive and

tribal culture, most of Art on this planet WAS and still IS (think to modern

architecture) due to power patronage."

Leaving aside my concerns with

your terms, "primitive and tribal cultures" -- that’s an ethnocentric world

view, if ever there was one -- my point is not to deny that power patronage

favours some artistic endeavours (which is obvious) but, rather, to suggest that

certain forms of religious power and certain symbolic conceptions of the world

inhibit the development of a CRITICAL, REFLECTIVE art

from.

Regards

Stephen

__________________

Stephen

Louw

Posted by Filiberto Boncompagni on 09-19-2003 01:09 PM:

Hi Steven,

"Primitive and tribal culture" must be intended here as

opposed to more complex and sophisticated ones.

I do not think that the

paintings in the Lascaux caves or the wall paintings of aboriginal Australia

were commissioned by some sponsor. Do you?

It is only when the society

becomes more complex with separation and specialization of tasks that it was

possible the appearance of the artisans or artists - i.e. persons specialized in

the production of certain types of object and the appearance of the customers

who could afford to buy those artifacts.

Is this ethnocentrism?

I

have no idea of who Gellner is, but I will be grateful if you could explain in

practice what is "art that seeks critically to interpret the social

universe".

When I say in practice I mean a concrete example: a painting, a

sculpture, a building.

Thanks,

Filiberto

it seems to me that this provocative

sentence is given

it seems to me that this provocative

sentence is given

You are right, Steve, the

word 'ridiculous' wasn't really necessary. I'll try to choose my words more

carefully next time.

You are right, Steve, the

word 'ridiculous' wasn't really necessary. I'll try to choose my words more

carefully next time.

,

Filiberto.

,

Filiberto.