Posted by R. John Howe on 09-07-2003 10:44 PM:

Baker on The Islamic Context of Moroccan Weaving

Dear folks –

I have looked a bit today into Patricia Baker’s book on

“Islamic Textiles.” Baker is clearly a westerner and it may be that like a

patient in a Freudian therapy session will unavoidably get it wrong, perhaps

only providing additional instances of the original complaint of western

misunderstanding. But in some circles, her work is admired.

Since our

task here is to better understand how Moroccan Muslims might have undertaken

their weavings in part as an expression of their religious beliefs, it seemed to

me that it might be useful to know (since there are many faces of Islam) what

specific species of it likely provided/provides such context. And if we could

detect some of the applicable rules, that would be even better.

Here are

a few quotes from Baker’s text:

“For guidance a Muslim will turn to the

Quran and then to the collection of the Prophet’s pronouncements (“hadith,”

generally translated as “Traditions). The “hadith” was gathered and verified

during the ninth century, and it is a responsibility of the “ulama” (Muslim

theologians, jurists and teachers) to advise and adjudicate on the sometimes

seemingly conflicting sayings. In the Sunni community there are four schools of

legal interpretation: the Hanbali (prevalent in Saudi Arabia), the Maliki

(Africa and South-East Asia), the Shafii (Eygpt and Syria) and Hanafi (Turkey

and Central Asia).”

This would seem to suggest that in a discussion of

Moroccan textiles, it is the Maliki school of Islamic legal interpretation that

is most relevant.

Next, Baker on some general Islamic history:

“On

the Prophet’s sudden death in AD 632, one of his close companions was elected by

the elders to act as caliph (khalifa: deputy) to lead the community, and this

procedure was followed thre more times…The selection of “Ali” the cousin and

son-in-law of the Prophet, as the fourth caliph in AD 656, was disputed by the

governor of Syria, Muawiya of the Umayyad family. On Ali’s assassination in 661

he assumed the caliph…These events marked a break in the Muslim community, with

the supporters of Ali (shiat Ali: the party of Ali) on one side and those who

accepted Muawiya as caliph on the other…Those Muslims who accepted Umayyad rule

maintained that the prophetic succession ended with Mohammed…Under the Umayyads

(661-750) these boundaries (ed. Syria, Eygpt, Iran and Iraq were already Muslim

beforehand) were pushed forward along the North African coastline and deep into

the Iberian peninsula.”

So the Moroccans are Sunni Muslims of the Maliki

school of interpretation.

Baker on seeming implications for Muslims that

might bear on weaving:

“Every aspect of a Muslim’s life is theoretically

governed or guided by divine law, the “Sharia,” and thus there is advice

relating to dress, fabric and colour as well as guidelines on the issue of

figural representation…Sunnit hadith generally holds that all figural

representations, human and animal are proscribed…Whether woven textiles are

included in the proscription has been debated by the ulama through the

centuries…”

Here is Baker on some Sunni rules concerning

fabrics:

Silk: “…theologians preferred to wear other fabrics. Silk may be

employed for men’s wear, but the amount and positioning depend on the school of

law concerned…All four schools agree that silk mixtures (that is, silk warp and

another yarn as weft) may be worn in battle, and indeed Maliki scholars allow

such fabrics at all times. Three rulings advise against sitting or leaning on

silk covers, but…Hanafi interpretations permit the practice.”

Baker on

Sunni rules concerning color:

“…White is considered in Islamic law as

most fitting for Mulim men…, it is the color for the Hajj and Muslim burial

attire, except for those killed in battle who may be buried as they fell…”

Green is the colour “associated with angels and gardens of Paradise…with

the descendants of the Prophet…” and “as the colour of Islam.”

“Attitudes could and did change over time. In his youth the Prophet

Mohammed has liked red but later he denounced it as Satan’s colour, although his

wife Aisha continued to wear it. In the later medieval Islamic world red was

linked with Mars, the planet of war, blood, passion and love and in both Seljuk

and Ottoman convention it was the bridal colour, however in Mamluk Eygpt it was

required dress for prostitutes.”

“According to Sunni hadith yellow was

worn by non-Muslims in the Phophet’s lifetime, and so along with blue, red and

black it was occasionally stipulated for outdoor dress for non-Muslims

(dhimmis). In eighth century Islamic society yellow signified a hedonistic

lifestyle, but 700 years later the wearing of yellow shoes was a privilege

bestowed on certain Ottoman court officials.”

“The idea of conducting

official business and receiving guests in curtained and draped surroundings

quickly percolated through Islamic society…North African sillks were also

popular.”

Apparent Islamic influence on motifs in fabrics:

“An

eleventh century silk made into a chasuble for the Quintanaortuna church, near

Burgos in Spain, develops the theme of connecting roundels containing heraldic

quadrupeds. Its inscription probably refers to “Ali, the Almoravid ruler of

North Africa and Iberia from 1106 to 1142.”

That’s what Baker’s book

seems to have that bears potentially on this salon.

Does it add anything

or add up to anything? Well, we at least know the specific school of Islamic

interpretation among the Sunnis that seems most relevant to Moroccan weaving,

but beyond that, I don’t know.

Regards,

R. John Howe

Posted by R. John Howe on 09-07-2003 11:28 PM:

Dear folks -

Here is one additional snippet from Patricia Baker's book

"Islamic Textiles." This one make no claim to apply specifically to Moroccan

textiles.

"Under Islamic law spinners and weavers were classed alongside

money-changers, tanners (and thus presumably some dyers), gold and silversmiths,

singers and dancers: that is, their trade placed them in some ethical dilemma,

say, exposure to ritually polluting stuffs [for example, the use of urine in

tanning and the preparation of "asb" (ikat) fabrics.] Conversely, the

occupations of bleaching, tailoring and dealing in linen stuffs were highly

commended by medieval Islamic philosophers. It is said that Khadija, the first

wife of the Prophet, was a linen merchant.

It was understood that certain

crafts required a greater level of skill than others. A block-printer was

apprenticed for four years whereas a medieval trainee weaver was bound for four

months."

I am not sure what to conclude from this but it appears that

weaving, in this comparison, was a less valued occupation in the Islamic ranking

of commendable and less commendable jobs.

Regards,

R. John

Howe

Posted by Filiberto Boncompagni on 09-08-2003 03:46 AM:

Thank you John for this contribution.

I have an article, "Textiles and

Colours in Islamic World" by Mandana Barkeshli, curator of textiles at "The

Islamic Art Museum Malaysia" in Kuala Lumpur.

The passage on colors is

very similar to Baker’s words - I guess one quoted the other.

Here’s some

more:

"Black became the identifying colour of the Abbasid dynasty, with

the Abbasids known in Byzantium and China as "black-robed ones". Sunni

theologians continue to wear black on formal occasions, while in the Shi'i

Islamic world, black, the colour of mourning and retribution, is also considered

powerful protection against the evil eye. This is a shared trait with turquoise

blue, which since the 14th century, has been a mourning colour in Central

Asia."

The following is also of interest, not for the understanding of

Moroccan textiles but for general knowledge:

"Besides considerations of

utility and availability of raw materials, people also derived regional or

national identity from their most characteristic textiles. Different regions

were known for their particular textile contributions. In Egypt, during the

Fatimid rule, silk tapestry bands with gold thread were introduced to the weave

of their already renowned linens. The finest silks of the Islamic world were

produced during the 9th-10th century in the Bukhara region of Uzbekistan, with

the production of the Zandanachi cloth, which originated from the village of

Zandana, and was developed for European export.

From the 10th to the 11th

century, the most significant centres of silk production was Iran, with silk

also produced in Baghdad, Egypt and Muslim Spain.

Despite Byzantine shipping

blockades, the silks quickly spread to Europe and eventually had a profound

influence on Byzantine, Sicilian and Italian weavers and

embroideries".

More on cross-cultural influences:

"The most

significant influences of Western textiles and dress in the Islamic world

occurred during the Ottoman reign (14th-18th century). Contemporary Italian

patterned fabrics were immensely popular, with thousands of ducats spent on

purchasing luxury fabrics from the Italian states, from as early as the reign of

Mehmed II (1451-81 AD). Imperial robes were tailored from 16th century Italian

velvets and silks, while others employed Italian-style motifs and patterns.

Reciprocally, Ottoman textiles had an influence on the design of various Italian

textiles. The ogee lattice and meandering stem motifs, as well as certain floral

motifs, such as the carnation, pomegranate and tulip, were incorporated into

designs of textiles from Lucca and Florence, the great centers of silk

production in Italy."

Regards,

Filiberto

Posted by Muhammad Thompson on 09-08-2003 06:39 PM:

Thanks John, we have not come across Baker's text and will try and read it.

There are some very useful sections of the hadith for those interested

in Islamic textiles and muslim tastes and mores - but perhaps we should say a

little about what the hadith are, or at least suggest people read about the

hadith and Islamic scholarship before diving into the texts themselves, (The

Broken Chain by A A Malik, 2001 might be of interest).

The traditions of

The Prophet Muhammad, the hadith, are collections of the things said and done by

the Prophet as these have been related by his contemporaries and passed down

from one scholar to the next. They are very important Islamic texts and allow

muslims to follow The Prophet's example in all, important respects. Knowledge of

and application of these precedents - which can have a legal status in Islam -

is the work of scholars; we are not scholars.

The hadith are now

published in four main collections. Imam Al-Bukhari's collection includes the

Book of Dress (volume 7, chapter 72) which includes many of the events in the

Prophet's life which resulted in the colour preferences and attitudes towards

pattern and picture which your extracts from Baker refer to.

Within this

chapter you will also find the incidents which provide the foundation for the

prohibition of pictures. The makers of pictures will receive the severest

punishment on the Day of Judgement. The Prophet refused to enter houses or use

garments or furnishings which were decorated by images of creatures. When The

Prophet prayed he disliked patterned clothes and materials to be in view since

they were a distraction.

TurkoTek contributore will notice straight away

that muslims have often not, in their architecture and arts generally, always

followed this lead and the use of pictures or statues of animals is quite

common. But our interest here is more confined to the arts of the Moroccan

muslims, and even more particularly to the Berbers or Amazigh tribes which have

produced kilims throughout north Africa.

I think there are many

different kinds of muslim in Morocco - there is the distinction drawn between

Moroccan Arabs and Berbers which has had a huge social and historical impact;

the majority are probably sunni muslim in outlook; the sufi saints and the

Berber muslim leaders have played important historical roles. We have suggested

elsewhere that Martin Ling's book on the Algerian Sufi (sufism = Islamic

mysticism) Shaykh Al Alawi is an interesting view into the religious lives of

muslim men in north Africa.

The history of the Berbers written by

Michael Brett and Elizabeth Fentress, (The Berbers, (Blackwell, 1997) is also an

interesting guide to this people united by a common language, which spans north

Africa and the Sahara. (So, "Moroccan carpets" is another label of convenience

since the Berbers who are responsible for most of their production, are spread

thoughout the Maghreb.)

Posted by R. John Howe on 09-08-2003 07:09 PM:

Mr. Thompson -

Patricia Baker's book is likely out of print but easy

to obtain on sources like the Advanced Book Exchange.

http://dogbert.abebooks.com/servlet/BookSearch

Here is

link to a specific copy in the U.S. (I don't know where you are.)

http://dogbert.abebooks.com/servlet/BookDetailsPL?bi=30350501

Regards,

R.

John Howe

Posted by Filiberto Boncompagni on 09-09-2003 05:24 AM:

MORE RESOURCES

Dear All,

This morning I casually discovered this website:

http://www.islamicart.com/

Interesting if you look for

resources on Islamic Art but you are not willing to buy a book.

Of particular interest are the link

to Islamic Architecture (that takes you to some decorative arts too):

http://www.islamicart.com/main/architecture/index.html

and

the one on Arabic Calligraphy:

http://www.islamicart.com/main/calligraphy/intro.html

The

site contains also general and historical information on Islam.

I was

really surprised by the examples of "Kufi" calligraphy in this page:

http://www.islamicart.com/main/calligraphy/styles/kufi.html

They

look so much like decorations that I would have never suspected they are

actually words. One never stops learning…

Regards,

Filiberto

Posted by Steve Price on 09-16-2003 01:19 PM:

Hi People

Muhammad and I have had some fairly pointed exchanges by

e-mail in the past few days, and he has objected to my saying that he asserted

that Islam includes "a strict prohibition on the depiction of the human". He

used this as an example of how his statements have been distorted by me and

others.

Here is an extract from Muhammad's earlier post in this

thread:

The traditions of The Prophet Muhammad, the hadith, are

collections of the things said and done by the Prophet ... passed down from one

scholar to the next. They are very important Islamic texts and allow muslims to

follow The Prophet's example in all, important respects. ... Imam Al-Bukhari's

collection includes ... the incidents which provide the foundation for the

prohibition of pictures. The makers of pictures will receive the severest

punishment on the Day of Judgement.

Muhammad is correct, this doesn't

say that depicting humans is "strictly prohibited." It only says that it is

prohibited and that those who violate the prohibition will receive the severest

punishment on the Day of Judgment. I stand corrected and hope that this clears

up any misunderstanding that I caused.

Regards,

Steve Price

Posted by Muhammad Thompson on 09-21-2003 01:06 AM:

correcting the correction

........ the substitution of "human" for "picture" is the non-trivial

distortion which I am sure Steve intended to bring to readers' attention in this

last post.

Posted by Stephen Louw on 09-21-2003 04:26 AM:

There is a useful article on Tasweer in Hali 116 (2001) by Richard Freeland.

Interestingly, Freeland points to the "aversion to images" in other religions

and their art forms, including early Buddist art, Christianity (especially the

iconoclasm movement of the 8th and 9th centuries) and Judaism (from which

concerns with pictorial representation stemmed originally).

Of interest

to our concerns, Freeland points out that "there is a noticeable distinction

between art in a religious setting and art in a secular or social environment.

Some hadiths [sayings of the Prophet] allow for the secular use of images, for

example the report that Mohammed objected to curtains decorated with living

things in the house but was satisfied when the curtains were cut up for cushion

covers. They were acceptable because of their different orientation as cushions

made them unlikely objects of prayer" (p.184).

Note, this does not imply

a strict distinction between secular and religious art – which is impossible –

but, rather, a comment on the usages to which beautifully decorated things and

art is put. It is only in extreme doctrinaire cases, which are the exception

rather than the rule, that all pictorial images are treated as idolatrous.

__________________

Stephen

Louw

Posted by Steve Price on 09-21-2003 08:00 AM:

Hi Muhammad

You are right. You never said depicting images of humans

is forbidden. You said making pictures are forbidden. It didn't say "strictly

forbidden", it said forbidden upon pain of the most severe punishment on the Day

of Judgment. I take this as meaning that it's forbidden to the maximal extent

that forbidding anything is possible. If "strictly forbidden" has to be stronger

than that, I can scarcely imagine what it might be.

I don't mean to be

picking nits, but I don't see anything in your text ( the one from which I

extracted a part to quote) that says it's OK to make pictures of humans. It's

customary (and logically impeccable) to extract specifics from general rules and

laws. That's the only practical way to have rules and laws. So if making

pictures is forbidden, making pictures of humans is forbidden. It seems to me

that to ignore this is a non-trivial distortion of what you

said.

Regards

Steve Price

Posted by R. John Howe on 09-23-2003 01:38 PM:

Dear folks -

Stephen Louw has suggested above that it might be the

"orientation" of a work of art with an image that made it acceptable or

unacceptable to some Muslim authorities.

The English student of such

things, whom I paraphrased in another thread, but whose book (which is here in

my apartment) I cannot find at the moment, suggested that it was also the "use"

to which the object so decorated was put. Again the chief concern seems to have

been to avoid infringing on God's creative function and idolatry. "Use" might

provide a clearer rule than would "orientation." (Stephen also used "use" in his

post but seemed to shift to "orientation" at its end.)

To take the

pillows example. It would be the fact that one would sit on them that would

suggest clearly that they were not intended as an item of devotion. Similarly,

this same authority argued that rugs with images hung on the walls was forbidden

but the same such rug might be permitted on the floor where it would be walked

on. Walking on things seems often in Islamic societies to entail denigration of

them. Note that some Iraqis displayed their disrespect, even possibly their

hatred of Sadam Hussein by striking his fallen statue with their shoes.

I

think it likely that Stephen is right about "orientation" but "use" seems even

clearer to me. Perhaps he agrees and there is no distinction intended in his

seeming distinction.

Regards,

R. John Howe

Posted by Steve Price on 09-23-2003 02:45 PM:

Hi John

The common conception among us westerners is that the Islamic

ban on images (albeit, not always followed) had to do with avoiding idolatry,

particularly if the images were of humans.

The passage Muhammad

presented above, part of which I quoted and which I think clearly includes

prohibition of images of humans, emphasizes a different reason - images are

distractions. Here's the relevant section from his post, which cites an

authoritative source:

The makers of pictures will receive the severest

punishment on the Day of Judgement. The Prophet refused to enter houses or use

garments or furnishings which were decorated by images of creatures. When The

Prophet prayed he disliked patterned clothes and materials to be in view since

they were a distraction.

My interpretation of this (correct?

incorrect?) is that images of creatures (humans and other members of the animal

kingdom) were prohibited. Patterns, on the other hand (and I presume that things

like stylized plants and vines are in this category), were permitted, although

the Prophet Mohammed disliked having them in view when he prayed because they

were a distraction.

My understanding of the basis for concealing women

behind their clothing and separating them from men in the mosques is that it is

also to minimize distractions. Women and men are separated in orthodox Jewish

synagogues, probably for the same reason (historically

speaking).

Regards,

Steve Price

Posted by Stephen Louw on 09-23-2003 05:46 PM:

Hi John and Steve,

Just to clarify, the term "orientation" is

Freeland's, not mine. Like John I prefer the term "use", although I don’t think

its that critical.

On Tasweer generally, I don’t know enough about Islam

to have a strong opinion about what it implies or prohibits. Certainly, the

hadiths are not clear or consistent, and, in any case, I am not sure how much

weight to attribute to these sayings as components of the Islamic

faith.

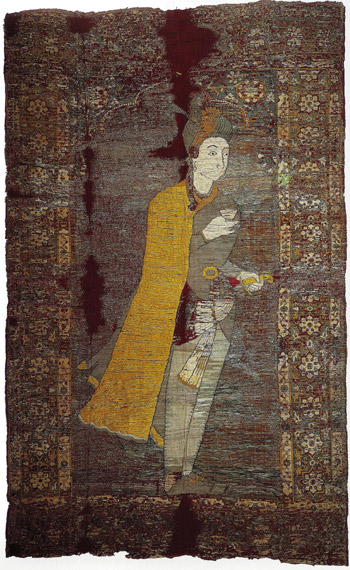

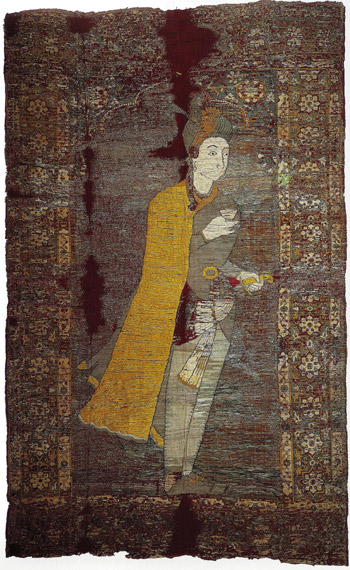

Some art that was clearly patronised by great Muslim leaders like

Akbar deliberately used human images: indeed, in one well-known carpet in the LA

County museum, this included an image of a courtier holding a wine glass (c.f.

Hali Annual 1994, p.78).

This latter practice (drinking wine) is clearly prohibited in

Islam, and drinking is not the subject of debate amongst Islamic scholars. Yet

Akbar chose to present this (or, at least, allowed his state-artists to do so)

as an image reflective of his court and its ethos. Indeed, he took wives from

other faiths to make a similar point about tolerance and religious

pluralism.

So I would caution about reading too much into the hadiths

about pictorial images cited by Muhammad. I don't think the issue of pictorial

representation is that clear at all and, as a political scientist, not a scholar

of religion, my suspicion is that the concern with pictorial representation is

an essentially modern concern, one strand among many within the pluralist

traditions of Islam that have been seized upon by anti-modernist Muslims, as

opposed to a clear and uncontroversial core doctrine. Much as wearing the veil

is an essentially modern response to the problems of the al jahili society [the

modern world that has lost its way], an attempt to re-affirm ones identity with

the (imaginary) world of the caliphate of old, where religious and social life

were (supposedly) integrated.