Posted by Filiberto Boncompagni on 09-21-2003 05:13 AM:

What is Islamic Textile Art?

Dear All,

One of the subject of discussion in our Salon is that to

understand Islamic Art you have to understand Islam, on which I agree to some

extent.

However, I have a lot of doubts in putting tribal textiles of Muslim

countries in a broad category called "Islamic Textile Art"

(the use of

"tribal art" has no depreciatory meaning but it is only an indicative of the

textiles' origin - as Jon Thompson’s distinction between, TRIBAL, COTTAGE,

WORKSHOP and COURT textile production.)

I already expressed some thought

on this subject in the "POLITICS!" thread and I’m not going to repeat them.

I think it is better to pass here from theory to facts and I’ll present

some scans.

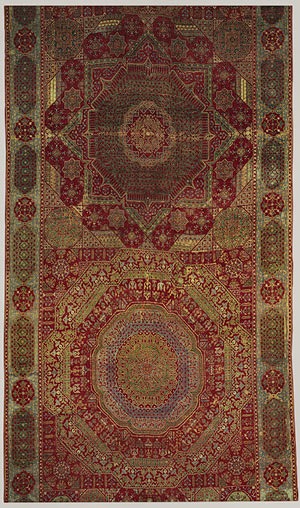

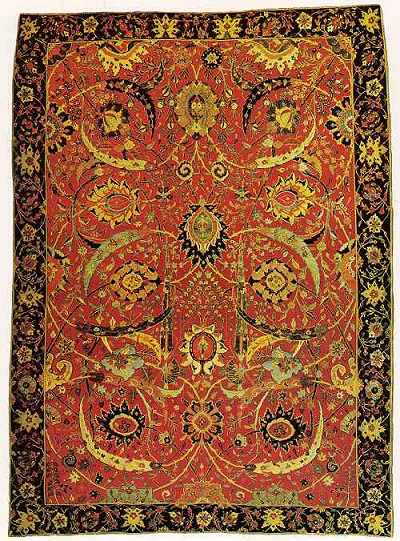

A Mamluk rug, the "Simonetti" Carpet, ca. 1500; attributed to

Egypt

courtesy of the Metropolitan museum:

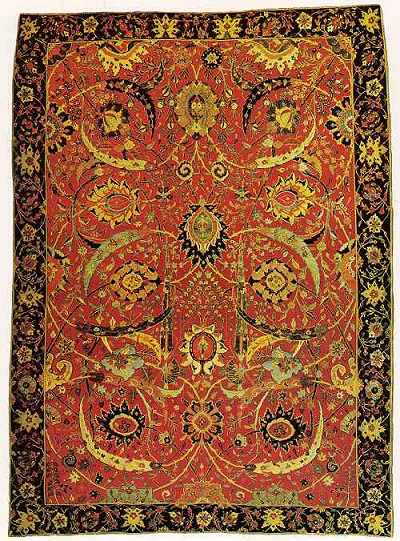

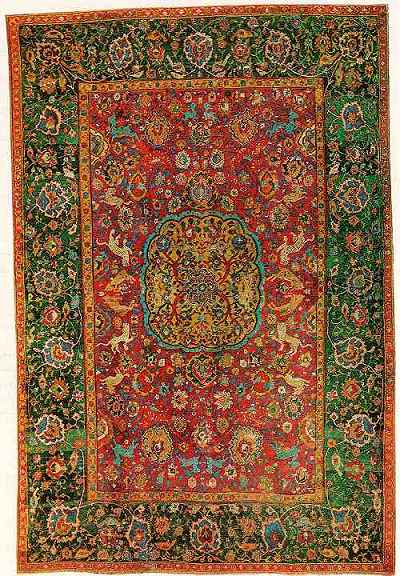

A Persian Shah Abbass design rug,

late 16th century, Corcoran Gallery of Art, Washington D.C.

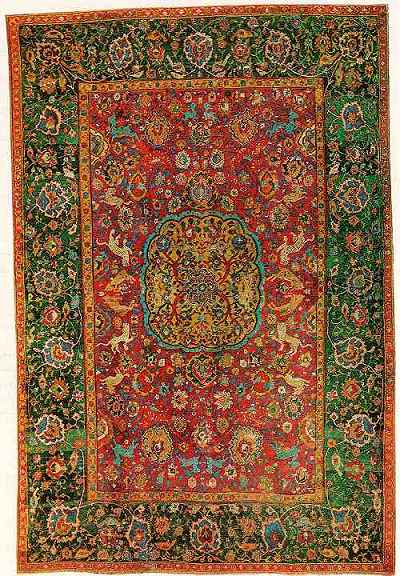

An old Persian rug, Floral and

Animal design, Juseph V. Mcmulllan collection, New York

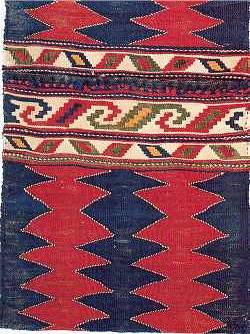

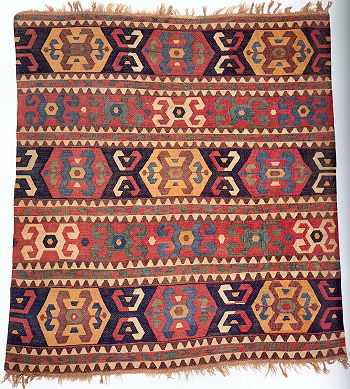

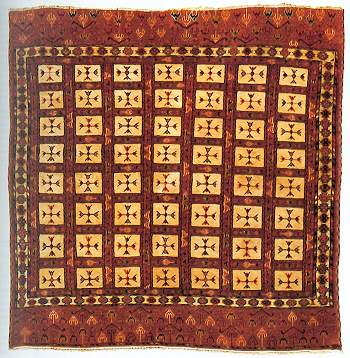

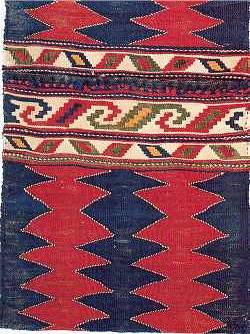

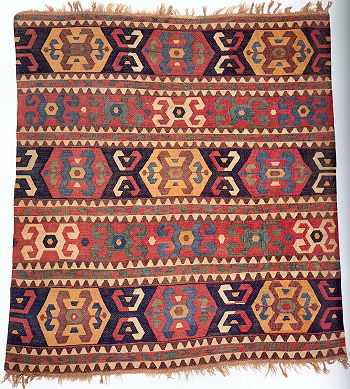

And these are 4 examples

of textile tribal or cottage art from Caucasus:

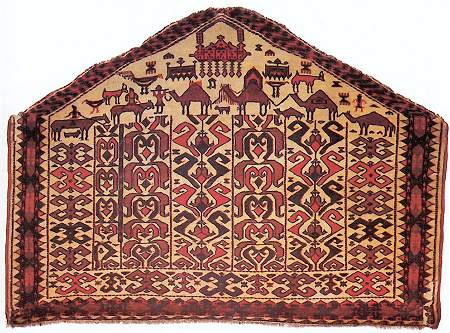

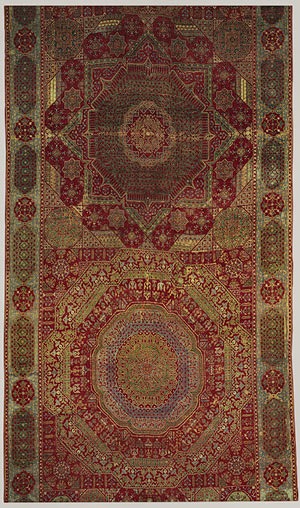

And 3 Turkoman:

What do you think about those

examples:

Do they all conform to Islamic art?

Do they all fit in the same

category of Islamic Textiles?

Best regards,

Filiberto

Posted by R. John Howe on 09-24-2003 05:00 AM:

Hi Filiberto -

It may be that you addition of the word "textile"

changes the basic shape of your question here but my own thinking is that Wendel

Swan's initial post in another thread, "What is Islamic Art?" answers your

question here about as well as it could be answered.

Is there something

here for you that moves beyond what Wendel has posted in that other

thread?

Regards,

R. John Howe

Posted by Filiberto Boncompagni on 09-24-2003 06:00 AM:

IT IS RIGHT TO CONSIDER TRIBAL ART OF ISLAMIC COUNTRIES AS

ISLAMIC?

Hi John,

Well, perhaps a different title should have been more

appropriate.

Like: IT IS RIGHT TO CONSIDER TRIBAL ART OF ISLAMIC

COUNTRIES AS ISLAMIC?

What I had in mind is to discuss the fact that,

while the first three examples of court/workshop carpets are decidedly Islamic -

to me, at least - the other seven "tribal" examples are not so clearly

definable.

So the answer is: YES, the addition of the word "textile"

should changes the basic shape of my question from a more general context to the

particular "tribal textile" one.

Best regards,

Filiberto

Posted by Stephen Louw on 09-24-2003 08:24 AM:

Dear Filiberto

I agree with your suggestion that "while the first

three examples of court/workshop carpets are decidedly Islamic ... the other

seven 'tribal' examples are not so clearly definable."

However, I think

that part of the problem, and this stems in large measure from our hosts’

presentation, is the tautological manner in which “Islamic Art” is defined. It

is hardly likely -- in fact it defines the imagination -- that illiterate

village weavers understood the tenets and prohibitions within Islam in the same

way that literate city dwellers understood Islamic doctrine. To suppose that

only weavings created within the strict confines of the formal (High) Islam of

the city mosque can be regarded as “Islamic art” is both simplistic and

tautological.

Anthropological studies clearly suggest that at a localised

level people tended to interpret (their version of) Islam through the prism of

extant spirit beliefs and mysticism. This is clearly the case in both Suni and

Shi'a societies. It is only under conditions of modernity, and through

industrialisation, that local weavers and local religious leaders came into

contact with city dwellers and the religious leaders of the city (High Islam).

In Iran, this did not occur until the late nineteenth and early twentieth

centuries. I see no reason why this synthesis of religious beliefs should be

seen as any less Islamic, unless one starts from the judgemental position of the

urban scholar or religious devotee.

Perhaps the best textile

documentation of this interaction between localised spirit beliefs and Islam are

the carpets illustrated in Opie's "Tribal Rugs". In particular, his exploration

of the relationship between the (pre-Islamic) mythology of early Luri bronzes

and pictorial representation in Fars weavings is suggestive of just this. In my

view, it is highly unlikely that these weavers even knew what Tasweer was, and

to suppose – as has been suggested in some of the discussion in earlier threads

-- that their use of pictorial representation undermines their commitment to

Islam in any way is ridiculous.

So I agree with your observation re: the

latter seven (very beautiful) examples of "tribal" art that you have presented

for us.

__________________

Stephen

Louw

Posted by Filiberto Boncompagni on 09-24-2003 11:50 AM:

Dear Stephen,

Glad to hear that you agree with me. Beware, this is not

a comparison based on aesthetics.

I would be more cautious, though,

regarding your affirmation: "It is only under conditions of modernity, and

through industrialisation, that local weavers and local religious leaders came

into contact with city dwellers and the religious leaders of the city (High

Islam)."

I am convinced that those contacts were much more ancient and

frequent than we are inclined to think nowadays.

COMMERCE (besides

Plunder and War) was the main reason for those contacts, and it wasn’t only the

legendary trade on the Silk Road. There were also lesser trades between nomads

(or semi-nomads) and cities over the N. Africa and the M.E.

The article

"TRADE AND EXCHANGE OF NORTH AFRICAN TEXTILE ACCORDING TO EARLY DOCUMENTARY

EVIDENCES" on the "Berber (Amazigh) history and society" thread gives some

insights.

See also this page on Richard E. Wright website:

http://www.richardewright.com/9011_yazd.html

especially

with regard to the Shahsavan.

Now I have to explain in full the reasons

for my doubts in defining those 7 examples of tribal/cottage textiles as

Islamic.

Let us begin with the Caucasian examples.

They all are scans

from Wright & Wertime "Caucasian Carpets & Covers".

The first, from

page 71 is attributed as Azeri or Tat.

The second, from page 135 is

attributed as Azeri or Armenian.

The third, from page 139 is certainly an

Armenian saddle bag: there is an Armenian inscription on the other face (not

visible here because I cut it out from the picture).

The fourth, form page

141 is an "Armenian cover (or possibly Azeri)".

A few considerations on

Tat, Azeri and Armenian ethnicity.

The origin of the Tats is obscure and

literary references are scarce. They have been supposed as being aboriginal

inhabitants of the Caucasus, who gradually, linguistically, iranicized, but

later, in the process of the forming of the Azerbaijani people, did not turn

Turkic. The complexities of their ethnic history are reflected in the fact that

among Tati speakers there are Muslims, Christians and Judaists.

The

Azeris are predominantly Shi'ite Muslims. They combine in themselves the

dominant Turkic strain, which flooded Azerbaijan especially during the Oguz

Seljuq migrations of the 11th century, with mixtures of older

inhabitants--Iranians and others--who had lived in Transcaucasia since ancient

times.

The Armenians are in the region since the 7th century BC, were

converted to Christianity about AD 300 and have an ancient and rich liturgical

and Christian literary tradition.

So, those textiles - with the exception

of the third - could have been woven by people of three different religions.

There is no way to tell which one from the style of the artifact itself, there

are no distinctive clues.

I know several Armenians here in the M.E. They

are very proud and defensive of their culture. I do not think their ancestors

could have copied patterns bearing close or even loose relationship with the

Islamic religion.

By the same logic, also the Azeri would have avoided to

copy a Christian design.

Now, look at the fourth example. Its design (or

at least variations of it) is found on rugs from Anatolia, Caucasus, Persia and

Central Asia.

James Opie suggests that it originated from Luristan, and

"Kurdish tribes in Iran and Anatolia served as a conduit for the passage of a

basic tribal design vocabulary from an area to the other".

My idea is

that some motifs, like this one, largely pre-existed current religions and were

already common heritage to people of different ethnicity. Sort of a textile

"lingua franca" if you like, that makes "politically correct" its adoption by

different ethnic groups.

Now for the Turkoman:

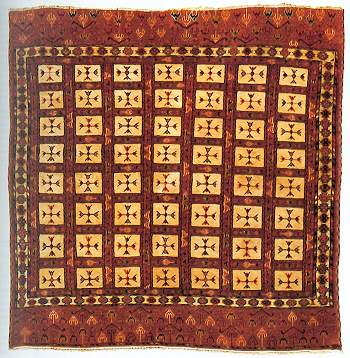

The first Turkoman

is a Yomut from Uwe Jourdan’s "Turkoman: Oriental Rugs". I chose it because the

design of its field reminds so much of the 3000(?) years old Pazyrik Rug and a

stone floor carving at Nineveh… (see Opie, page 33). Not too much of Islamic

influence here.

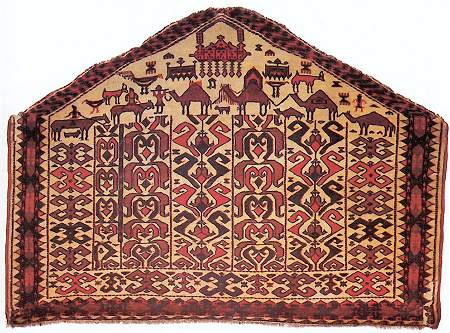

The second Turkoman, a Yomut Asmalyk is also from

Jourdan’s book.

The apex is closed by the depiction of a "tumar" - a

container for amulets. The rest of the composition with its wedding caravan and

the field decoration (with motifs that remind me of designs from central Asian

felts) has very little of Islamic, in my opinion. I see more an older Shamanic

culture, there.

The last is Dudin’s Ersari-Beshir. I chose it, in spite

of it being a prayer rug because I think the horns-like motifs (Kotshaks) are

probably much older than Islam… and because I like it.

Conclusion:

Uh… do I really have to write a conclusion? It’s already a too long

posting…

Best regards,

Filiberto