Posted by David R. E. Hunt on 09-06-2003 07:17 PM:

Intentional Mistakes?

All- Granted, while it may at times seem that these "intentional mistakes"

are proffered as excuse for weave defects, I for one am not so sure that this

concept is merely an imaginative sales pitch for faulty merchandise. This faulty

corner resolution, advanced by the authors as substantive evidence, does seem a

wide spread and common weave phenomonon- it seems to me readily apparent that

these corners could easily resolved if the weaver actually wanted to. Also, I

must admit that in many of the weave defects that I have encountered, it seems

hard to believe that the weaver could not have noticed, or for that matter have

not corrected many of these mistakes-those faulty constructions of interior

details of design elements in which the surrounding , often intricate design

remains unscathed immediately come to mind- any published research on the

subject? So ofen, in folktales, rumor, and even predjudice, there lies a kernel

of truth- so what of this?- Dave

Posted by Steve Price on 09-06-2003 09:39 PM:

Hi David

My brain spins a bit every time I see the phrase "intentional

mistake" used to describe some unanticipated (by the western viewer) alteration

in design or color. The essence of something being a mistake is that it is not

intentional. So, I prefer to call them irregularities.

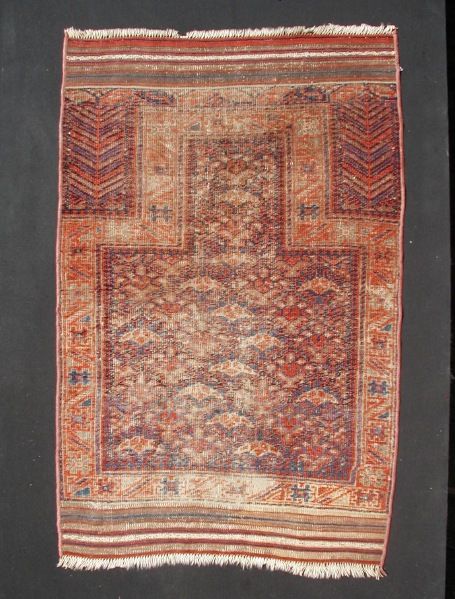

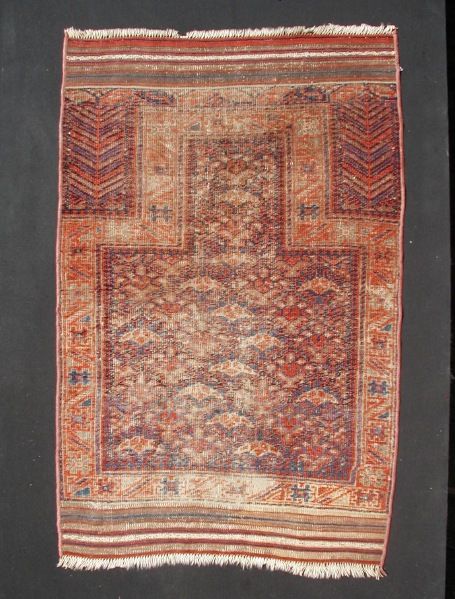

Let's take a look

at one of the examples Muhammad and Nasima presented.

Here's a very obvious

irregularity. We can ask some questions about it. First, is it an error (that

is, was it done unwittingly by the weaver)? Clearly, it is intentional. That was

easy.

The next question isn't, though. Since it was done intentionally,

why did the weaver do it? One hypothesis, put forth by Muhammad and Nasima (and

by many others before them), is that it is essentially a religious act, an

acknowledgement of the necessity that anything man-made must be imperfect. I'd

think this is a testable hypothesis, the simplest test being to interview some

of the weavers and ask them. It's possible that they wouldn't always answer

truthfully, but it would be a pretty good way to start. They might say exactly

what Muhammad and Nasima say. They might say something else that makes sense.

Either way, that approach seems a much better path to the truth than either

insisting that the hypothesis must be correct or insisting that it must be

incorrect.

Regards,

Steve Price

Posted by Filiberto Boncompagni on 09-07-2003 04:04 AM:

Dear All,

I have little doubt that the above example is a deliberate

anomaly.

I agree that a widespread explanation for these anomalies is of the

sort "perfection belongs only to Allah".

My humble opinion is that it looks

like a device against the ancient universal superstition of the evil eye -

renamed with a new "Islamic politically correct" label.

Syncretism DOES

exist in Islam.

A further corroboration to my opinion is that such

deliberate anomalies are found all over the tribal/rustic Oriental rug world -

but are also CONFINED there. Tribal/rural societies are more likely to preserve

old superstitious habits than the urban ones.

Yes, I wrote "tribal",

although our hosts seem not to agree with the term - or at least they seem to

attribute to "oriental rug collectors and writers" a somehow inferior

valuation:

There is a tendency among oriental rug collectors and

writers to view these textiles as tribal and primitive as opposed to

decorative/aesthetic and meditative; to look to the Amazigh (Berbers) as a

pastoral people rather than as amongst the builders of the high art of

Marrakech, the Alhambra and Muslim Spain. This western view is condescending at

best.

Well, considering that most of Westerner oriental rug

collectors value tribal rugs MUCH more than the decorative ones, I think the

misconception, dear Muhammad and Nasima, is yours!

Let my continue with

anomalies: you see them as an act of devotion by the pious Muslim

weaver/artist.

If this is the case, why don’t we found deliberate anomalies

in workshop or Court carpets?

(At least, if they are any, I’m not aware of

them. I’m open to contrary evidence.)

And why don’t we found examples of d.e.

in other forms of Islamic art - say, metalwork or architecture?

Are there any

examples of deliberate anomalies in the Alhambra, Ibn Tulun Mosque or Taj

Mahal?

As I said, I’m open to evidence.

Best

regards,

Filiberto

P.S. Steve is right: the simplest test being to

interview some of the weavers and ask them.

Posted by Steve Price on 09-07-2003 07:54 AM:

Hi Filiberto

I believe Muhammad and Nasima are correct in saying

There is a tendency among oriental rug collectors and writers to view

these textiles as tribal and primitive as opposed to decorative/aesthetic and

meditative; to look to the Amazigh (Berbers) as a pastoral people rather than as

amongst the builders of the high art of Marrakech, the Alhambra and Muslim

Spain. This western view is condescending at best.

The fact that we

(you and me and most of Turkotek's readership) value tribal and village art more

than workshop art doesn't contradict that at all. In fact, one of the great

attractions of tribal art to many collectors is the opportunity to vicariously

participate in exotic, primitive cultures, with interesting superstitions (I

should add, superstitions that are interesting because they are so different

than the ones that abound in our culture).

The same phenomenon can be

seen among collectors of African tribal arts, the value of which has an

extraordinary dependence on the likelihood that a piece was used in tribal

ritual.

Regards,

Steve Price

Posted by Filiberto Boncompagni on 09-07-2003 09:20 AM:

Hi Steve,

Perhaps. Or perhaps not.

My understanding of those

sentences is that trying to distinguish between ‘tribal Berber people and/or

their art’ AND the ‘urbanized Berber people and/or their art’ is condescending

at the best.

Is my interpretation correct ?

The answer to our hosts,

please.

Regards,

Filiberto

Posted by Filiberto Boncompagni on 09-07-2003 09:44 AM:

Or better:

there is only ONE Amazigh (Berber) entity, the builders of

Alhambra etc. SO we cannot separate the art they produced under pastoral

condition from the high art of Marrakesh

etc.

Regards,

Filiberto

Posted by Patrick Weiler on 09-07-2003 01:31 PM:

Intentional Imperfections Misguided

I do not know the origin of the "intentional imperfection" tradition. Is it

actually noted in any specific religious text?

The concept appears to be

nonsense when considered logically.

If only God can make things perfect,

and if

God made everything, then everything is perfect.

If God made you,

then you are perfect and everything that comes from you, having come from God,

is therefore perfect.

Taking this another step further, even the

"intentional imperfections" are thereby perfect.

Darn.

Perfectly

Patrick Weiler

Posted by Muhammad Thompson on 09-07-2003 03:12 PM:

Filiberto, please do not overestimate our knowledge - we are not experts. We

would like to know more about the "evil eye" as a possible cause of anomalies;

we are ignorant of this. (I must say we are sceptical of this approach to the

textiles just as we would be impatient with someone who tried to describe a

Constable landscape by reference to the English superstitions of walking under

ladders, black cats or broken mirrors.)

I am sorry Filiberto, we haven't

studied the buildings and the art forms you suggest to know if anomalies are

found in the same way as these textiles. It is a good question but I think

wherever the artist is in a position of working for someone else, anomalies are

likely to be much less apparent if they exist at all.

What we did do in

the article was describe two types of anomalies in kilims - one is obvious, the

other more concealed - and we suggested that whenever the artisan is employed or

commissioned it is more likely that the anomaly will be inobtrusive; they will

be more careful to avoid the financial loss resulting from someone considering

the work defective. Where they work alone and especially when they weave for

their own homes, the anomalies can become much more a part of their style.

Yes, the views of the weavers should be critical in our efforts to

explain, understand and appreciate. Marla Mallett's website is one of the few we

have come across that mentions conversations with weavers in this

respect:

"Rigid, mechanical-looking "factory" rugs and other weavings

have short-lived appeal; in contrast, one can quickly grow fond of the

irregularities that occur routinely in village and nomad textile art. Abrupt

changes in color, motif or proportion reflect a carefree, lively attitude toward

the work. Such anomalies are not considered mistakes, nor are they signs of

inept work. Unmatched pattern repeats rarely bother the weaver; many indeed are

purposeful. I have heard women laughingly dismiss peculiar design irregularities

in their work as "more interesting." I have seen mothers reluctant to correct

their daughters' work. Weavers are unconcerned by erratic shifts in warp fringe

color, unconcerned when their weavings are irregularly shaped. We too must

realize that the essential qualities in this folk art are freshness, vitality,

pleasing color, superb materials and excellent design."

Given that this

notion has done the rounds (over some years?), shouldn't the paucity of other

hard data on this topic, tell us something? Perhaps contributors will come to

our rescue in the days ahead.

Posted by Ali R.Tuna on 09-08-2003 05:29 PM:

In all this discussion with Intentional mistakes and if is it linked to

religion , we can also turn our look to the court carpets and textiles from the

Islamic countries. Who , better than the Sultan , his court members and the

"Ulemas" (religious leaders) would be better representing the official doctrines

and interpretations of the religion.

Yet , in all carpets and textiles made

for the court and the elite class, we find a sense of perfection which was

considered as the quintessence of the carpet art. At least we know that at their

times , this is what was seen as the "best". This has also continued till

present times (see the Persian carpets made for the rulers , even today"s silk

Herekes made for the Gulf countries etc..).

Even the abrash - so sought

after today- and probably is also an effect of the time rather than the original

manufacture, was considered as an imperfection and a mistake.

If we look

at the other art forms in Islam , i.e. the miniature , tilework , bookbinding,

it is difficult to sustain that what was considered as an imperfection or

mistake was deliberately introduced to confirm modesty versus God's creations (

Patrick Weilers logic seems flawless to me) .

So the "easy explanation"

of the imperfection introduced looks more like carpet dealer's arguments than

anything else (there are obviously more affordable carpets than the court

carpets- I do not consider the less perfects artistically inferiour

though).

This said , we should not rule out that the introduction of

assymetries , irregularities and other interruptions of the order were

introduced as a deliberate artistic effect. Especially , not knowing the real

context in which these works were executed (time gone by and weavers not willing

to share) we might be "mistaken" to interpret them in the current

context.

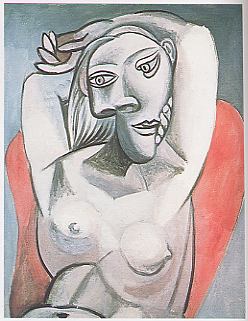

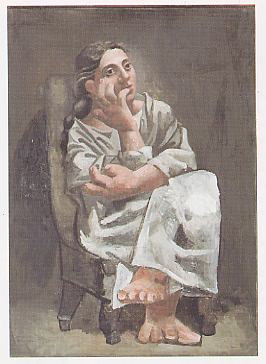

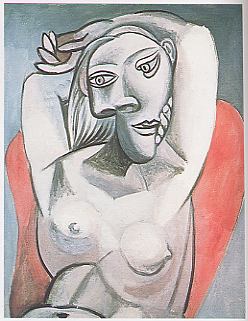

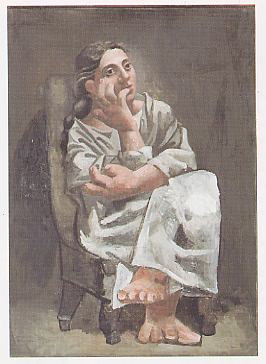

I am posting two paintings below , that , interpreted within the

Renaissance context would be full of mistakes but also full of charm (Two

Picassos).

They are obviously full of "mistakes" anatomically , but is there

a parallel we can get from there for our textile mistakes?

There are huge differences

between today's Islam as some people interpret and tend to define it and the

free thinking that the original religion has created with all the scientific and

artistic curiosity , experimentation and also fraternity it has created . Within

that context the encouragement for sciences , exactness , logic thinking and

order (that were all reflections of God's properties) I can not imagine the

lesser quality creation could be imputed to the religion.

As such , I

tend more to embrace the "atomist " explanation where the introduction of the

singularity through regularity has a philosophical importance (not that people

philosophed when weaving but this thinking has generated a mind set and a style

of designs) in the Islamic view of the construction of the Universe (Just think

about the Big bang) .

By ordering the basic elements the same way in some

order is an act of prayer like "tesbih" (like a chaplet) meaning repetition of

the name and reality of God in this world , than changing it once and starting

again in a slightly modified order goes to the base of the islamic philosophy.

This is different than the rhytmic orders obtained by normal tribal

art.

This goes beyond in its search for new combinations in the infinite

and in its beauty. This is how several of the nice ornamental patterns were

created.

This is why I believe that some singularities can be necessary in

islamic art , like the silences in a music sheet before a new pettern/order

starts.

Ali R.Tuna

Posted by Muhammad Thompson on 09-08-2003 05:30 PM:

Patrick's question

Sorry Patrick, I can't share your logic but I would like to try to respond to

the question you began with:

We don't know of any religious ruling about

this topic for the specific activities of weaving, the arts or crafts; the idea

was related to us by a Meknes rug dealer. (There are very clear prohibitions on

the making of "pictures" - we will refer to these in another strand.)

The

situation however, is a familiar one for muslims, we think.... and easily

understood by anyone who has made something?

Any small successes we have

in creating or making something often results in us pausing or even dwelling

upon and marvelling at what we have done. A certain amount of pride is evoked by

our handiwork and we may even become a little blind as to its shortcomings. If

the object we have made is always around to catch our eye and imagination, or

the activity a frequent one for us, a great deal of time can be wasted and pride

engendered by the objects created. For someone who considers pride to be a sin

and the time spent being proud to be time wasted, some techniques need to be

devised to divert these tendencies.

The anomalies in some Moroccan

kilims, may provide such a technique; a free and easy attitude to the weaving

(described on Marla Mallett's website and quoted above), may be another method

of avoiding this pitfall of the creative process: a muslim should not become

attached to the earthly things. Pursuing perfection in an art or craft can

therefore have its dangers.

We will try to expand on our understanding of

the Islamic attitude towards human, creative behaviour, in the strand,

(Baker....) which John has started; in brief, the pious muslim attempts to gain

knowledge of the attributes of Allah and to share (in a small, human way) those

attributes. The muslim need be ever mindful of the difference between the human

and the divine. Man is evidently not perfect but struggles for the salvation of

his soul.

Posted by Steve Price on 09-08-2003 06:36 PM:

Hi Muhammad

I noticed in your Salon essay, and was reminded in your

last posting, that you and Nasima tend to refer to Muslim practice as though

there was only one variety; one set of ways of doing things. I have a number of

Muslim friends, students and colleagues, and have visited Turkey 5 times. My

observation is that there are probably as many variations in the the practice of

Islam as there are of Christianity. The core beliefs may be the same for all

Muslims, but the specific practices aren't.

Turkey's population is

virtually entirely Muslim - the government is strictly secular (even more so, in

some respects, than that of the USA). In Tokat, seeing a woman with her hair

exposed is unusual. In Istanbul, most women dress as westerners. They are all

Muslims in a Muslim society.

Your last post mentions a strict

prohibition on the depiction of the human, but there are lots of rugs from the

Muslim world with humans drawn pretty realistically, some showing specific

individuals. Last night I was browsing old Christie's catalogs and ran across a

15th or 16th century Turkish manuscript page that included a color picture of

The Prophet Mohammed. I'm not sure what all this proves, but it is inconsistent

with a strict prohibition on Muslims depicting humans. So, I suspect the strict

prohibition applies to some branches of Muslim practice, but not to all.

It will complicate our thinking somewhat, but it's probably useful to

either specify the range of variation within rug-related practices or focus on

those practices that really are nearly universal among the

Muslims.

Regards,

Steve Price

Posted by Muhammad Thompson on 09-08-2003 07:47 PM:

Dear Steve

Yes I am sorry if we gave the impression that Islam was

monolithic; your observations on its diversity are correct. No two people will

practice the religion in quite the same way. No two people will understand it in

the same way or find it easy to follow in exactly the same way.

(We feel

poorly equipped to answer many of the questions which are now emerging about

Islam but we welcome their emergence.)

You said that our "last post

mentions a strict prohibition on the depiction of the human"; I think we

actually said "a clear prohibition on pictures", and it is usually interpreted

to mean "pictures of living creatures".

As we say in another strand

(Baker .....), this is not upheld at all times and in all places despite the

apparent clarity of the hadith. Representations of people, even of The Prophet

(usually veiled), are not hard to find. Today, pictures in the broadest sense of

that term (ie including photographs), are found throughout the muslim world.

Differences in scholarship, in interpretation of the The Qur'an and the

hadith, are probably the primary reason for this diversity.

Yes, let's

confine the discussion to the local interpretation of Islam as it unfolded in

north Africa and it's effect upon the textiles produced by the Amazigh?

Posted by Steve Price on 09-08-2003 08:12 PM:

quote:

Originally posted by Muhammad Thompson

... let's confine the

discussion to the local interpretation of Islam as it unfolded in north Africa

and it's effect upon the textiles produced by the Amazigh?

Hi Muhammad,

I think this will help to keep us from

getting into a lot of confused and confusing circles. Thanks.

Steve Price

Posted by R. John Howe on 09-09-2003 07:19 AM:

Dear folks -

Just to connect Steve's indication above with some other

information we have in this salon in another thread, there is a section in one

of the links on Islamic art that Filiberto has provided (I cannot find it again

at the moment) which says approximately that Moroccan artists do not indulge

much in figural representation but that the Persians have always exhibited a

taste for it.

Just a related point that I cannot ducment either at the

moment because its source is "lost" somewhere in my library here. I have read a

treatment of this issue by a long-time British student who expressed great

disdain for most explanations of such differences. He especially rejected the

wide-spread view that the Persians use more figural representation in their art

than did other Islamic cultures because of they were of the Shia

faction.

He pointed out that all of the factions of Islam have their

authorities and all of these discouraged the use of figural images in art, the

Shia included. His explanation of the fact of figural usage by Muslim artists in

Muslim societies was that, as with all other faiths, there are Muslims who hold

their beliefs more closely and some who hold theirs more loosely and who do not

always adhere with precision to all the prohibitions.

He also presented

quotations from history, including some claiming to be from Mohammed's own

household in which the thrust of the prohibition seemed to be two-fold. First,

artists were not to take on to themselves any of God's creative function in

their art and second to make sure that idolatry did not occur as the result of

the use of figural images. So, this authority said, one might not use figural

images on a textile that was to be used in a mosque, or one that was to be

placed at home on a wall, or one that was to be worn. But it MIGHT be

permissible to use figural images on something that was being walked on, such as

a carpet.

But it appears that the Muslims in Morocco mostly observed the

prohibition against figural images in their art. At least I have not found a

textile with human or animal figures in any of my Moroccan rug

books.

Regards,

R. John Howe

Posted by Filiberto Boncompagni on 09-09-2003 09:56 AM:

Hi John,

Your "British student" is probably right. Perhaps Persians

where more indulgent on figural representation for their historical and cultural

identity - let us say for a sort of nationalistic pride.

I’m told by an

Iranian acquaintance of mine that "portraits of Prophet Mohammad and Ali

Miniatures can be seen everywhere in Iran. Go to Isfahan and you will see tons

of pictures of depicted human figures on the walls…In Chel Sutun in Isfahan,

different battles are depicted during Safavid time".

This should be one of

them:

I found out that we can find frescoes with human depictions

also in Islamic buildings outside Persia: in the Umayyad and 'Abbasid palaces

and in Spain, and in the harem quarters of the Mughal palaces in India.

There

is an example here in Jordan: Umayyad castle, Qasr Amra, 8th

century.

Those

were secular buildings, though. The prohibition Was enforced for sure on

religious buildings all over Islam.

Regards, Filiberto

Posted by Filiberto Boncompagni on 09-09-2003 11:14 AM:

Dear All,

I think you should enjoy this mosaic pavement from another

Umayyad building: Khirbat al-Mafjar, a complex consisting of a mosque, a castle

and elaborate baths near Jericho, c. 740 AD.

The mosaics in the baths consist

primarily of geometric patterns with the notable exception of this one.

The

subject has been interpreted as an allegory: the gazelles peacefully nibbling

the leaves of the tree on the left symbolize the blissful state under the

Umayyad rule. The right side represents the wrath of the Umayyad caliph against

his enemies.

Filiberto

Posted by Filiberto Boncompagni on 09-09-2003 11:20 AM:

Uh, sorry, re-reading the thread I realize I am definitely digressing…

Regards,

Filiberto

Posted by Michael Bischof on 09-09-2003 02:11 PM:

...cannot imagine !

Hallo everybody, dear Muhammad Thompson,

I can talk only about my own

experience. Never ever I heard such a thing from weavers or villagers in Iran,

Syria or Turkey - just several times from carpet dealers in the big centres. It

sounded for me a bit wrong: these people are fond of oral communications and do

not sport to read books. The way they explained it sounded "written", reciting

something one has read somewhere...

I must admit they I never had

long-lasting close contacts to member of the Intelligentsia in these countries

so how they feel and express that I do not know.

quote:

The muslim need be ever mindful of the difference between the human and the

divine. Man is evidently not perfect but struggles for the salvation of his

soul.

Believe me: if you are a weaver or a villager who deals

with wool or dye stuff plants you do not feel about to forget the difference

between the human and the divine - by creating a carpet! Your experiences,

troubles and worries about the piece are so much "from this world" that there is

no temptation in this direction . When the middle men of the cottage industry

enterpriser come and cut some of the agreed upon money claiming slight detail

mistakes you would feel tempted to the opposite side: it would have been better

to compete harder with God in the direction of perfection and total

harmony...

According to what I know carpets have never been made by rich

city dwellers who occasionally sat in their garden and, like with a hobby, from

time to time felt the need for some artistical self-expression so they sometimes

moved such philosophical thoughts in their brains ...

In short: I cannot

imagine that this idea ever played any role in such a Near or Middle Eastern

country side environment where carpets were made. May be, just a phantasy, the

well-educated director of an important court workshop had such ideas. But not

his weavers ...

Regards,

Michael Bischof

Posted by Muhammad Thompson on 09-10-2003 04:12 AM:

Re. the wisdom and good taste of kings, governments and the

intelligentsia

Dear all,

I am sure I am not alone in thinking that there are all

kinds and grades of scholarship and governance. Certainly in Islamic history

there are what are often described as "the rightly guided caliphs" (Abu Bakr,

Umar and Uthman and Ali, may Allah be pleased with them) and those that came

after.

And in the field of scholarship, there is a long tradition in

Islam of scholars needing to avoid and distance themselves from all kinds of

patronage in order to maintain their duty to Allah and intellectual honesty.

We will not be surprised to find that leaders, muslim and non-muslim,

often procure scholarly support for ends which they find convenient but which

have poor or non-existent intellectual justification.

So I don't find

arguments based upon some "courtly standard" of good taste or scholarship to be

automatically convincing. Sometimes the purest manifestations of belief are

found amongst the lowliest not the highest members of society. I have tried to

describe on a new thread (Berber history...) why this might be an important and

motivating factor for Berbers who led the equivalent of a protestant reformation

in their country on various occasions.

I don't know why the Persians did

produce pictures; it is possible their scholars did not know of the hadith in

question or chose to follow other false hadith. I think there are known

instances where hadith were fabricated in order to justify the desires of the

powerful. (There is an account at page 524 of "Islam: Art and Architecture", eds

Hattstein & Delius, which describes the emergence of figurative painting in

the Safavid period; this book attempts to chronicle some of the disputes

regarding the topic throughout muslim history.)

... and because I am a

fan of the writings of the great, twelth century scholar, Imam Al Ghazali, allow

me to recommend a reading of his introduction to his Book of Knowledge; we do

not know exactly who it is addressed to but it is a wonderful, flowing and

stinging attack on scholars who have obscured the religion to please the rich

and mighty. (You can read an excellent translation by N Faris at http://www.muslimphilosophy.com/gz/default.htm this website is

an excellent source of material for this important muslim theologian and

philosopher. "The Faith and Practice of Al-Ghazali" translated by W Montgomery

Watt is also a wonderful read and very accessible source book for non

muslims.)

Posted by R. John Howe on 09-10-2003 07:42 AM:

Mr. Thompson -

Just for the record the Mamluk Muslims also used

figural images including some "in the round" sculptures. Such instances would be

more relevant to this salon, and might require more explanation, since the

Mamluks would seem, like the Moroccans, to be Sunni Muslims of the Maliki school

of interpretation

Of course, one of the difficulties here (and it is not

particular to Islam) is how is one to identify reliably the "rightly guided"

authorities?

I should also be clear about the boundaries of my interests

in this salon. I am interested to know more about how Muslims view the weavings

we collect and how their descriptions and interpretations might be distinctive

from those of us with western backgrounds, but I consider all evangelistic

efforts of all faiths to be immoral. Even those that use only verbal persuasion

rather than the sword. So I am not interested in examining Islam as a possible

personal creed.

Regards,

R. John Howe

Posted by Bob Kent on 09-10-2003 08:28 AM:

deliberate irregularities in weavings

Weavings from many makers and a great range of time have intentional design

irregularities. For one example, I really like the deliberate irregularity in

the pattern of the kilim at the start of this thread. There is no reason to

believe that one reason can or should explain all or even most deliberate

irregularities. Deliberate irregularities might sometimes be there as gestures

of religious humility, sometimes to break the monotony of the weaver's task,

sometimes to "sign" a work (like the human hair in some yuruks), sometimes to

enhance aesthetics, sometimes to enhance market value by giving an older look,

and sometimes for more than one of these reasons. Perhaps we see fewer

deliberate irregularities in for example geometric tiles or illuminated

manuscripts because they were made for a place or purpose where the point was to

provoke the awe-inspiring feel of an infinite geometric repeat and a design

irregularity would detract from this effect. The tiles and books we see were

more often created for religious contexts and purposes than weavings were? Or

perhaps an aesthetic difference exists between media: irregularities are more

likely to enhance a weaving than a miniature, tile mosaic, etc.

In any

case, thanks to the authors, is a different and interesting perspective.

Posted by David R.E. Hunt on 09-13-2003 12:37 AM:

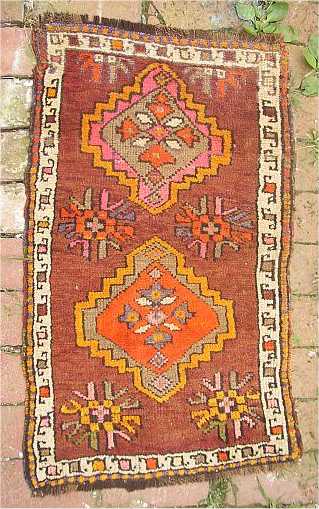

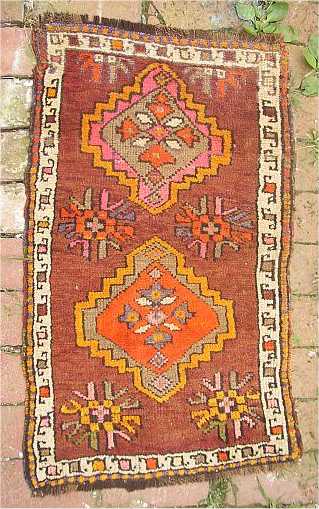

Transitions and Irregularities

Dear All- Just some examples of corner transitions and irregularities in

various weavings- Dave