Posted by Steve Price on 08-06-2003 08:14 PM:

Inferences from the soft colors

Hi Davut and Erhardt,

As you note and show nicely in the examples, one

of the characteristics of Manastir kilims is that the colors are "soft". You

make an interesting hypothesis from this observation: The slightly subdued

tonality of most Manastirs is probably to be ascribed to intensive use and the

resulting frequent washing. That is, you propose that the palette was much

more saturated when the pieces were new.

There is an alternative

hypothesis, which is that the colors might have been subdued to begin with.

Since some of them were used for floor coverings, some as wall decorations, and

some for a variety of other things, I would expect some to have been subjected

to intensive use and frequent washing (the floor coverings and eating cloths,

for instance), while others were used very gently and probably were seldom

washed (the decorative wall coverings).

If the first hypothesis is

correct, there should be two fairly distinct classes of Manastir kilims with

regard to color intensity. The ones that were lightly used and seldom washed

will have something like the original (more saturated) colors. The more heavily

used pieces will have a subdued palette from being used and washed many times.

If, on the other hand, the palette was subdued right from the start, there might

not be a subset of Manastir kilims with a palette of saturated

colors.

Having seen a great number of these pieces, do you find two

classes with regard to color, or are just about all of them characterized by the

subdued palette?

Regards,

Steve Price

Posted by Patrick Weiler on 08-09-2003 07:01 PM:

Rugs, too.

Steve,

I recall having seen some "Manastir" kilims with less soft

colors. The kilims with blue fields can give the impression of being less soft,

and having more contrast when juxtaposed with red motifs.

As so little is

known conclusively about Manastir kilims, perhaps some similar kilims made

elsewhere are attributed to Manastir, too.

And then there are the

Manastir rugs. They seem to have a similarly subdued palette. But again, maybe

rugs with colors similar to Manastir kilims have merely been labeled Manastir.

Are Manastir rugs also available in two flavors, subdued and

bright?

Patrick Weiler

Posted by R. John Howe on 08-10-2003 08:52 AM:

Hi Patrick -

If you have Hali 112, you can see the examples that

Bertsson provides of Manastir rugs. Most have milder colors, but there are a

couple with strong orange-reds and yellows.

Bertsson says that it is the

older types of Manastir rugs that have the milder colors "on a background of

natural beige wool" (another technical indicator?) and that it is the more

recent ones have the more saturated colors typical of Anatolia.

One of

the interesting things about yellow (Chris Walter has told me) is that it can be

obtained from a quite wide variety of plants and so there can be variation in

the character of the color obtained simply because of

that.

Regards,

R. John Howe

Posted by Richard Tomlinson on 08-11-2003 07:25 AM:

hi

i am not sure how worthwhile this may be, but it is food for

thought.

firstly, let me quote a section from peter davies' book on

kilims 'the tribal eye' (bits of a section as i don't really feel like typing it

all :-)

he is talking about dyeing;

>>>>

"the

truth seems to be, sad to say, that despite all the weight of custom and

tradition and the obvious worth of all that had been achieved, the Anatolian eye

grew to prefer synthetic colors. .....................

Even in the older,

naturally dyed kilims it is evident that tribal weavers in their exuberant

celabration of color had always favored the clearest and brightest hues they

could achieve, and exploited to the fullest the color potential of the natural

palette..................

It would appear that tribal cultures around the

world...........have retained these natural

inclinations"

>>>>>>

bearing these comments in

mind, (and davies may very well be way off track) i would like to ask - if this

is the case - why would a group of tribal weavers DELIBERATELY set out to

achieve softer, muted colors?

i am inclined somehow to agree with Davut

and Erhardt that the muted tone was not a deliberate

intention.

thoughts?

richard

Posted by Steve Price on 08-11-2003 10:19 AM:

Hi Richard

I don't know of any tribal group (or, for that matter, of

any nontribal culture) that didn't adopt synthetic dyes about as soon as they

were able to do so. It's us - the collectors of antique textiles - that are out

of step in this sense.

My guess is that the reasons include the

aesthetic appeal of the expanded palette, and reduced cost. Whether the muted

tones of Manastir kilims was intentional (original) or the result of fading due

to use and washing would be pretty easy to determine: pieces used for wall

coverings should have more or less their original colors. Were they muted or

bright?

Regards,

Steve Price

Posted by R. John Howe on 08-11-2003 04:26 PM:

Dear folks -

I don't think there's much doubt about the color

preferences of the "tribal eye" world-wide. It seems to me that it almost

universally favors the brightest colors that can be produced at a given time. (I

think that's close to what Davies is saying.)

My hypothesis for the

existence of muted colors at weaving is that these were the shades that could be

produced in a given area at that time. As soon as brighter shades are available

most tribal weavers tend to go to them like homing

pigeons.

Regards,

R. John Howe

Posted by Richard Tomlinson on 08-12-2003 06:18 AM:

hi john, steve, all

john - you wrote;

"Bertsson says that it is

the older types of Manastir rugs that have the milder colors "......) and that

it is the more recent ones have the more saturated colors typical of

Anatolia"

what is confusing me here is the question of differentiating

manastir kilims from 'other' anatolian kilims.

it seems to me (and

please bear in mind i am a complete amateur collector) that there are people in

the rug world who use this 'unique feature' of 'soft' colours to differentiate

manastir kilims from other anatolian kilims. it seems that manastir kilims have

a reputation of having 'soft' (and for the collector, very appealing) colours.

and as patrick points out - perhaps other rugs/kilims have been called manastirs

because of this focus on tonality?

but what about older anatolian kilims?

surely they too were washed, and have consequentially faded over time? is this

idea of manastirs being softer just a myth?

is it not the CHOICE of

colours / colour combinations that manastirs exhibit that, once faded, makes

them 'uniquely different' rather than the extent to which they are faded?

or were manastirs actually dyed differently?

thanks

richard

Posted by Steve Price on 08-12-2003 06:50 AM:

Hi Richard

There are a number of images of Anatolian kilims of great

age in Salon 91 . The colors are saturated and vibrant, and I doubt

that anyone would describe them as subdued.

My guess is that the

Manastirs were dyed with a subdued palette to begin with. I've tried to reach

Davut Mizrahi to see if he can cast more light on this question (and some

others), but have not been successful so far. August is vacation time for many

Europeans, and perhaps he is away.

Regards,

Steve Price

Posted by R. John Howe on 08-14-2003 08:37 PM:

Richard, Steve -

The absence of our hosts so far is unfortunate.

We may be at the point of demonstrating to one another that one cannot

become rich by pooling poverty.

BUT, Bertsson indicates and gives

examples of pile rugs that he attributes to Manastir weavers. Most are of milder

colors, but a couple are rather bright. He describes the latter as more recent

and suggests that they exhibit more typically Anatolian colors.

I doubt

that we can tell at this point whether the shades we see in the examples we find

are primarily the result of fading over the years (one would certainly expect

some but some Anatolian pieces from the 15th century exhibit bright, saturated

colors) or whether they are close to those selected by the weavers when these

pieces were woven.

We need our hosts.

Regards,

R. John

Howe

Posted by Michael Bischof on 08-19-2003 05:02 AM:

soft colours

Hallo everybody,

quote:

( this is the first time since I read Turkotek that a host is absent. What is

the reason ? I thought a host is the initiator and a kind of contributing

moderator after the start of the salon. Naive ? )

I am bit confused.

quote:

"

The colors of the Manastir kilims have been described as exceptional

in the few texts about the group. Their unique palette and some of their

technical characteristics have made these textiles distinct from mainstream

Anatolian kilims. It is these qualities that make it possible to differentiate

them from their neighboring Sarköy kilims. But the two share only a few

elements from a store of patterns, the origins of which are primarily to be

sought in the Sarköy. "

I find these lines vague. What means "exceptional" within

this context ? The pictured pieces show soft

colours but I agree that with

the exception of kilim 3 (upper row, the outermost right one) one cannot see

whether this impression is caused by heavy light oxidation/patina or by using

"soft" ( dyes which are done with unsufficient saturation ) dyes. In the latter

case this would point to the possibility that the weavers themselves may have

made them. But the most common dyes are red and blue and these people normally

never made on their own but let the professional dyer do the job.

Many

Manastir pieces that I have handled had not "soft colours". They were quite

"strong" and saturated.

The oldest piece named/claimed "Manastir" that I ever

met I should mention here. It had an eye-dazzler kind of design but made so that

one easily could prolong the piece in both vertical directions and in both

horizontal regions as well. The most uncommon feature was the combination of

extreme fine warps and very thick and heavy, soft warps. The dyes were of the

same quality and saturation that one would expect in a +/- 200 years old

Anatolian kilim ( but I do not know, of course, whether this particular piece

was made there). I sold it to a friend who displayed it in London in the middle

of the eighties. To whome it was sold both of us have

forgotten.

Greetings,

Michael Bischof

Posted by Davut Mizrahi on 08-21-2003 06:35 AM:

hi John,

hi Steve,

Sorry that it took a little long to answer

(better to say to try to answer) your questions but as you noted before we have

now in Austria around 35 to 40 degree celcius temperatures and we were out of

town for couple of weeks.

In the original surroundings of their

culture-on the Balkans we like to presume-the pieces had a clearly defined

function in the householdings, when the old concept of culture fell apart in the

new surroundings (new homes and neighbours) the pieces had to fulfill different

purposes. Nobody became rich from being a "muhadjir", it impoverished people

leaving them with a reduced property. So in a new need of multifunction a before

highly estimated kilim stepped down from the wall to the table or even to the

floor when coming into age.

The colors:

There are a number of kilims

which could be called „brightly colored“, in our book for instance the plates

27, 30, 37; but one could find others which have not suffered from use so much.

These could probably be „dowry“ pieces. But anyway there actually is a strong

tendency towards a softened palette: the blue used in most of Manastir weavings

is Woad and not Indigo. With woad as a dye one cannot achieve such saturated

blues as with indigo. This fact gives another starting point to a color scheme,

depending from the mid-blue of woad. It makes black well the deepest color in

being darker but not deeper than the saturated indigo coloring. This has

certainly some influence on the further choice of colors/dyeing.

To the

4th question by John:

1- We mentioned the spin of the wool in our comment

to plate 7 in the book; the strong spin of the yarn would indicate the use of

„Zackel-sheep“ wool with ist shorter staple. The Manastir-people knew of the

curved weft-technique from the Sarköy-people, but it was difficult for them to

immitate it.

2- About Berntsson’s knowledge of Manastir Kilims see Hali

113/letters, with an answering letter from Sonny Berntsson. Concerning the

usefulness of his article on pile rugs, I must admit, that it is still the best

written device to place the Manastir Kilims in a cultural context. The most

important difference between these two components of a culture is that pile rugs

seem well to have been made for trading as an issue from the Manastir –culture

to the outside, the flatweaves on the other hand made to look inside the culture

to fulfil the task of protecting within.

3- There are conventional borders,

i.e. continueing pattern surrounding a centre-field on all four sides equally,

on Manastir Kilims of the later period. By the way there are a number of other

tribes which do not have a surrounding border but merely side-endings and

differently patterned skirts at the ends.

4- In the 70‘s the market started

to label certain types of kilims „Manastir“ or more cautiously „Westanatolian“

but in any case „muhadjir“. The dealers themselves had been told by descendants

of „muhadjir“-people that these were the kilims to the allready known Manastir

rugs to the market. So it need not to be a mere constructed label from the

carpetdealers. On the other hand I know of many carpet names which came to light

exclusively by the trade.

A very important feature of Sarköy kilims is, that

all inscriptions on them are in Cyrillic characters, whilst the only writing I

know on Manastir kilims is in Arabic, which means that Manastir people were

turkish and Sarköy people were more likely Serbian or Bulgarian.

Our

opinion on the examples in „Kilim“ by Hull and Luczyc-Wyhowska: their plate 250

is certainly Manastir, the same type as our Nr.35 by Boralevi in the book, plate

253 is a Westanatolian of origin possibly Kütahya?

The B&W illustration

in the next shows to our opinion a Maccedonian weave; the Maccedonians weave in

stripes of a 70-80 cm width like it is told in the text to the

illustration.

With regards

Erhard & Davut

Posted by Michael Bischof on 08-22-2003 10:29 AM:

woad again ...

Hi everybody, dear Davut,

wow, you present here a sensational

fact:

quote:

"But anyway there actually is a strong tendency towards a softened

palette: the blue used in most of Manastir weavings is Woad and not Indigo.

With woad as a dye one cannot achieve such saturated blues as with indigo.

This fact gives another starting point to a color scheme, depending from the

mid-blue of woad. It makes black well the deepest color in being darker but

not deeper than the saturated indigo coloring. This has certainly some

influence on the further choice of colors/dyeing."

This is, until now, only the second record of the use of

woad in Oriental textiles ! How did you get it , is it published somewhere yet ?

Your second sentence is wrong, though: "With woad as a dye one cannot achieve

such saturated blues as with indigo". This is simply not true.

Woad is the

only known plant that delivers the whole spectrum, including red ! Well, not a

real great red, but "kind of red" ... and you could, if you know and if you

like, create a blue as dark as you would like to have it . You would simply have

to use a big amount of woad then...

Greetings,

Michael Bischof

Posted by Michael Bischof on 08-28-2003 07:19 AM:

missing informations ...

Hallo everybody, hallo Davut, hallo R. John Howe,

I want to insist

that if there is material concerning the use of woad in Manastir kilims it

should be presented here. - In case you cite it from your book, Davut, this is

welcome as well ! => Do it !

R. John Howe: everywhere in the world one

can use about 20% of any local flora to make yellow dye lakes. It is even

possible to get the famous open-clean yellow (one of two shades that one usually

finds in early dragon carpets)

from a very common ruderal plant called

Löwenzahn ( French: piss en lit ... ) . I guess we had shown that in 1985 at the

association of rug connoisseurs in

Northrhine-Westfalia.

Regards,

Michael

Posted by Michael Bischof on 08-28-2003 09:15 AM:

woad and dandelion...

Hallo everybody,

in the meantime I got a mail telling what "Löwenzahn"

is:

"Löwenzahn = dandelion in this country, probably "diente de leon" was

its

origin. Yellow composite flowers in spring, young leaves good to

eat.

"Dandelion" is very common here on the East Coast, as are many

other

European field plants, mostly brought early to North America by

English

colonists with their grain stores or with other live plants brought

on

ships."

Yes, we like to eat the young leaves because they have a nice

slightly bitter aroma. But it releases things from the urea bladder quick - pay

attention ! The yellow colour of the flowers is useless for textile

applications.

In the meantime I studied the Manastir book.

The

reference to woad is from Berntsson , but in this moment I do not have HALI,

112, at hand. - Is there a result of own field research quoted, some laboratory

result, or is it more or less like

"somehow unusual, somehow Turkish" =>

Konya (1985), => Karapinar (2003) ?

Regards,

Michael Bischof

Konya Karapinar

Posted by Michael Bischof on 08-31-2003 08:24 AM:

Hallo everybody,

now I have the book at hand ( thank you, Davut !) and

the following lines are based on the pictures in the book ( which I can

recommend !) and on the digis in the salon. Extra for this contribution I worked

out a short

essay about lacquers ( dye lakes) which is hopefully helpful

for understanding this discussion.

Both assumptions that Steve had put

here seem to be true:

- most colours in Manastir kilims seem to be

professional strong dyes that later faded by heavy use ...

- some (few) are

"minor" dyes that most likely people might have done themselves. These faded

much quicker .

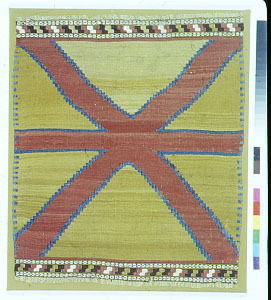

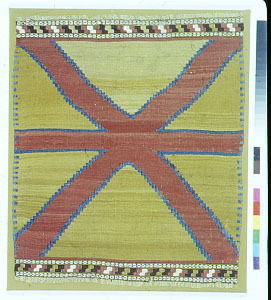

Plate No. 1 ( Davut, are you able to send a

digital photo to this thread ?) is a striking yastik. The strong red is vivid

and has a blueish-pinkish cast - the hallmark of a good madder dye. I assume it

is professional dye.

Piece No. 1 ( in the salon : upper row, left ) has a

dull, brown-red "red". This is the typical result that appears if people

"do

it on their own". With the same tone but a far weaker saturation it is what the

people in Turkey today call "imalat kirmizi",

"production red". This

particular piece has not been used a lot.

In piece No. 4 ( salon, lower

row, left) there are two qualities of red: a low quality brick-brown-red in the

border and a good red

surrounding the central niche.

Piece No. 3 ( salon,

upper row right) seems to be a late piece with some amounts of decaying ( ;-) -

yes , again this damned word !) dye qualities : a synthetic violet

( or a

really pale madder violet - I mean pale even at its "birth") and a typical, but

common and age-independant minor dye ( brown from walnut shells).

All the

Indigo dyes seem to be professional fermentation Indigos. The alternative method

to work with fermented urine is technically inferior unless the dye master has a

really impressive experience - such dyes I cannot see in these pieces.

If

one compares no. 11 in the book with no. 12 and 13 one has a brillant comparison

for the dye quality/colour combination schemes of (relative) early and late

pieces not only in this book but as well in all Anatolian kilims.

Piece No.

17 should be compared with this Avanos

kilim , 309 x 166 cm, which is on exhibition again since yesterday. On

Tuesday more about this event ! It is an A-piece from Cappadocia and is ( though

not older, more likely even younger ) by far the better kilim in my opinion. For

sure it has nothing to do with Manastir - kilims.

To summarize it: the

occurrence of minor dyes in such type of kilims is, especially if it happens on

a big scale, a hint for a late

date but not (!) in the sense of a

k.o.-argument. At the ICOC in Milano we discussed a regional group where this

happens regularly even in quite early pieces - some of them being exhibited

again right now.

Again: who has access to the Berntsson - article should

be so kind to send the material about the facts on the use of woad here

!

Regards,

Michael Bischof

Posted by Sue Zimmerman on 09-01-2003 11:34 PM:

WOAD WAR #... I forget

Hi Michael,

One thing about woad that isn't "more psychosomatic than

real" is "Woad Warrior", BASF's EPA approved herbicide for killing woad. Sue

Posted by Sue Zimmerman on 09-03-2003 10:46 AM:

Hi Michael,

Time is money, yes, but in our civilization the really big

money is in slow killing. Over here, for those who don't know, failure to thrive

is the result of too much money burdening one's pockets. Thankfully, in our

modern buildings which most resemble temples, hospitals, we are relieved of our

burdens, and likewise our heirs are relieved of added burdens too.

Amen.

I shall be buying woad seeds but the dye pot will not be the first

place my Ingotin A will be used. Do I think big bu$ine$$ knows more about woad

than I do? You betcha I do. Sue

Posted by Steve Price on 09-03-2003 10:56 AM:

Hi People

This seems to me to have the seeds of a political discussion

embedded in it, and I'd be grateful if those who want to engage in them do it

somewhere else. That is, Sue's post is as far as we're going to go along the

lines of whether big business is good or evil.

Thanks,

Steve

Price

Posted by Michael Bischof on 09-03-2003 01:25 PM:

again soft colours ...

Hallo everybody, hallo Sue,

puh, what a pity : what we declare to be a

valuable dye source, the woad

plant, is a kind of pest for you ? Yes, if you

have no use for it ...

Again the queston of "soft colours":

what I

write here is based on my interpretation of the color prints in the book

-

whereas these following pictures are 39 kB - jpg-images. This makes much

more

than a slight difference ;-)

One can see clearly that they had tried

to "load" the fiber with the dye lake

as good as they could. As far as I can

see the Indigo is natural Indigo from a

professional fermentation vat. The

yellows have been once very saturated, of the

Quercetin - type

The difference seems to be the

red. I tend to assume that the blueish-rosy-red

of the yastik is a

professional dyer's work , as well as the deep maddder browns

in both

pieces.

In the

second piece the madder is a once saturated but later

slightly faded kind of

(red-brownish-brick-) red dye that is typical for "self

made reds" from

Afghanistan to Morocco. It fades because it simply is less good

( less fast

against all environmental influences, not only against light ).

When it fades

its tone shifts to a slightly more clear red ( the blueish part of

the shade

is a bit enhanced ) but the dye lake looses a lot of volume and gets

kind of

spotty and matt. There is no reason to assume that people wanted it like

that

- but one may suppose that they wanted to save money by doing

it

themselves.

Here the quantitatively most important dye is yellow so

this "madder defeat"

does not mean too much. But in many antique pieces, not

only in Manastir weaves,

this effect shifts the original intention that the

weaver had on colour

combination - she looked at fresh unfaded dyes when

setting up the weave - and

a more or less heavy aesthetical problem

arises.

Piece no. 25 in the book shows this problem in a striking

amount.

I agree with the authors attitude that these two pieces are a

kind of

"highlight" in this publication.

Regards,

Michael

Bischof

Posted by Michael Bischof on 09-06-2003 03:46 AM:

urgent correction...

Hallo everybody,

uff, the

colours in the above given plates look

wrong.

These pictures I got from Davut Mizrahi ( thanks a lot !).

But my interpretation

is based on the colour plates in the book

quote:

Erhard Stöbe: Manastir Kilims. In Search

of a Trail. Eine Spurensuche.-

Vienna, 2003. feichtner & mizrahi fine arts.

-ISBN 3-9501158-6-2 ( Text

in English and German, 46 colour plates )

- and they differ to a big extent from these pictures.

Please just believe

me that the yellow ground colour in both pieces is the

same and not

the light lemon-yellow of the above shown yastik

picture.Here we talk about

dyes. This is not a matter of interpretations but

of science.

One can test it by suitable experiments. When I said that

this is a more or less patinated Quercetin dye-lake you can verify or

falsify this by doing an easy experiment in your kitchen. All you need is the

description that I prepared on how to make such a

dye - and then

you may get peppermint, Melissa officinalis or birch leaves or olive

leaves or .... 20% of any local flora on this planet would release this

dyestuff.

quote:

For 10 g wool yarn you need 250 g fresh plant material - or 50 g

dry

material(at least !).

Then you can create the most saturated dye lake (lacquer)

that you can obtain and let it patinate (oxidize by light) for 1-2 months behind

your window glass. Then you will have the ground colour of nearly all Manastir

kilims that are discussed here.

Regards ,

Michael Bischof