The Salon du Tapis d'Orient is a moderated discussion group in the manner of the 19th century salon devoted to oriental rugs and textiles and all aspects of their appreciation. Please include your full name and e-mail address in your posting.

by Steve Price

Tribal attribution of Turkmen pile textiles is fairly reliable. That is, except for a small number of pieces, we have good objective criteria by which to assign any Turkmen textile to a particular tribe; often to an even finer level. This is not the case with Turkmen flatweaves, for which we have almost no criteria from which to make tribal attribution. The pile decorated tentband is another genre that in which it is extremely difficult to determine the origins.

Why is this? Tribal attribution of Turkmen pile weavings is based mainly on the structure (especially knot type), palette, motifs, and materials. Tekke, Ersari and Chodor weavings are almost always knotted asymmetric, open right; Saryk and Yomud are usually done with symmetric knots. Cotton or silk are seldom found in Yomud pieces. There's no need to go on in this direction; the point should be clear. If you know the criteria and have the piece in your hands, making a tribal attribution that would be accepted by most collectors is generally not difficult.

How do we know that those criteria are correct? For the most part, it is because there are a number of pieces of documentable tribal origin, and by recording their characteristics it becomes possible to develop attribution criteria for each tribe. For example, if a piece has lots of cotton and symmetric knots it is almost certainly Saryk. Look at enough Saryk pieces (identified by those criteria), and the Saryk palettes and motif vocabulary emerge; they can then be used for attribution.

Things are not so simple with pile decorated tentbands. Structurally, most are done with symmetric knots over three warps, with wool warp and weft. Motif vocabularies look quite different than what is seen in any tribe's pile woven pieces, although we can sometimes pick out related forms. Palette can be useful, but in the absence of other criteria it is difficult to make use of it.

To make matters more difficult, there are very few pile decorated Turkmen tentbands with documented tribal origins. The Rickmers collection, for instance, includes four Turkmen pile decorated tentbands. Rickmers collected them at the tribal sources around the year 1900, so he probably knew (or would have been able to find out) their tribal origins. Evidently, he did not record this information. Robert Pinner, who wrote the descriptions in the published catalog of the collection, hesitantly suggests that one is Yomud (on the basis of the palette having a brownish red) and that another is Tekke (on the basis of the plaiting of the ends). Some published sources attribute tentbands to specific tribes with what appears to be total confidence, but the foundation for such confidence is unclear to me. In most cases, I suspect that it is simply by reference to published tentbands that have been given attributions on the basis of little information. That is, many published tentband attributions may just be errors that have become accepted through repetition.

I would like to get us into a discussion of this subject with a tentband that I bought some years ago at Sotheby's. It was catalogued as Yomud, but George O'Bannon declared it to be Tekke in his report of the sale for Oriental Rug Review. Neither he nor Sotheby's explained their attributions. There are two published tentbands that are very much like this one (palette, width, design, end finish, use of silk, border pattern, and motifs). One is plate 97 in Azadi's Wie Blumen in der Wuste. Azadi attributes that piece to Salor? (question mark in original), and dates it to the 18th century or earlier. The other is plate 14 in Elmby's Antique Turkmen Carpets II. Elmby believes it to be Saryk and estimates that it was woven in the first half of the 19th century.

The dimensions are 44 feet long by 10 inches wide. I've run into a few knowledgable dealers who believe that the relatively narrow width (12 to 15 inches is more typical) indicates that it was woven before the mid 19th century. I don't know whether this is correct, although the piece under consideration appears to have only natural dyes. This suggests that it predates 1875.

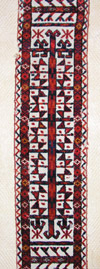

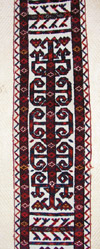

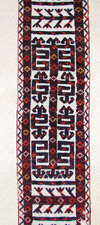

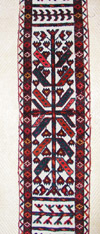

Showing a piece with these dimensions on a web page presents problems similar to those encountered when trying to display it. It's too long and too narrow for the usual approaches. Mackie and Thompson resolved this in Turkmen by displaying each of two tentbands horizontally across the tops of three consecutive pages. I show the one here as consecutive overlapping sections, beginning at the end woven first. These are fairly small, low resolution images (under 20 kb each), which permits the page to download in a reasonable amount of time even in a dialup connection. Each is linked to a higher resolution, larger version (70 to 100 kb), that can be displayed by clicking your mouse on the small image. I also have very high resolution images that I can provide to anyone who would like them.

The width is 10 inches, so you have a built-in dimension scale in each image. Here is the end woven first, and the first five panels. It might be convenient to refer to them as "End 1" and "Panels 1-5" for discussion purposes.

|

|

|

|

|

|

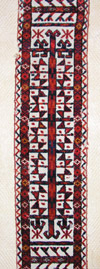

Remember, the part woven first is at the top and progresses toward the end woven last (Yon, please note the well-defined internal elem in the first panel). Click on any image for a larger version of the same one. The next series of images are Panels 6-11.

|

|

|

|

|

|

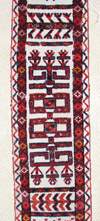

Just a reminder. Every image is linked to a larger version of the same image, and we are progressing from the end woven first to the end woven last. The next series of images are panels 12-17.

|

|

|

|

|

|

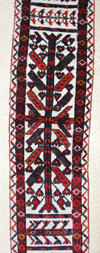

Just a reminder. Every image is linked to a larger version of the same image, and we are progressing from the end woven first to the end woven last. The final set of images are Panels 18 and 19, and the end woven last.

|

|

|

Let me say a few words about this piece. It is wool on wool, with silk highlights in gold, dark blue, and magenta. The pile is extremely fine. There's little point to giving a knot count because each knot goes around three warps, but the pile is about as fine as any Turkmen pile weaving that I own.

Who made this tentband? The motifs don't help very much, in my opinion. Most are outside the mainstream we associate with Turkmen pile bags and trappings (which is true for all tentbands, of course). Motifs that look as though they are related to Yomud "pole trees" are easy to find, and three of the panels seem related to the main motif in the field of Beshir prayer rugs (pomegranate trees?). The palette could be Tekke, Saryk or Salor, and the presence of three colors of silk is consistent with any of those possibilities. The method of finding something similar in print and using the same attribution would assign it to Salor or Saryk. The piece tentatively attributed to the Salor by Azadi is incomplete. It is the first of the final two images. The piece that Elmby attributes to the Saryk is shown beneath it. Azadi's example is 10 inches wide. Elmby does not provide dimensions for his, but it appears to be about the same (the difference in width on the photos is probably almost entirely due to differences in enlargement).

So, I leave you with some questions to ponder. Who do you think made this tentband and, more important, why do you think so? Do you see a sort of a grammar to the motifs of the panels and to the short segments that divide them from one another? Do you see fairly obvious relations between some of the motifs and those found on the more usual Turkmen products (pile weavings)?