Posted by R. John Howe on 06-01-2003 08:23 AM:

A Well-Designed Salon, Worth Taking On

Dear folks and Tom -

I have been away since May 14 and so just read

Tom's salon this morning.

I am not a collector of Baluch pieces and don't

really study the distinctions being made, but do remember DeWitt Mallory, the

NYC Baluch collector, coming to the TM a few years ago and saying that, if he

had given his talk that day ten years previously, he would have a lot more to

say about Baluch weaving. But, he continued, we have discovered that:

1.

We do not know who the "Baluch" were for sure.

2. We suspect now that many

pieces that we call "Baluch" were not in fact woven by Baluch weavers.

3.

With on or two exceptions we are not sure where most "Baluch" rugs were woven

(Tom seems to disagree about this aspect).

4. And with one or two exceptions

we are not sure who wove the rugs we call "Baluch."

He then gave a

presentantion and a walk-through of the exhibition drawn from the Jeff Boucher

collection (which Mallory had curated) that was noteworthy for me in what it did

not attempt to say about the pieces. It was very, very bland indeed and I think

deliberately so, since DeWitt's position on Baluch weaving that day seemed to

accentuate a claim that things had actually gone backward with regard to

knowledge as learning about "Baluch" weaving advanced. [Very different from the

claims of Jerry Anderson during Tom's interview with him or of the seemingly

aggressive attributions in Michael Craycraft's older writings. (Michael told me

once that he had taken Jon Thompson to task for giving up prematurely on his

"Imreli" claims, which Michael thinks are correct.)]

I've seen something

similar happening with some Turkmen analysis. I see more pieces labeled

"Turkmen" without a tribal attribution nowadays and some of the "gods" of

Turkmen analysis have begun to say "not Ersari" without indicating what the

alternative might be.

Now while I've slipped into talking about

"attribution" in this last paragraph or two, I'm clear that Tom is advising that

he thinks it is more advisable to talk about "provenance," and I want to say,

most centrally in this post, that I admire the design of this salon and mean to

embarrass myself publicly in the next week or so, by taking on its useful

task.

I have designed a few salons with such tasks and think that taking

them on, as posed, is likely a useful undertaking. I notice that many simply

ignore such salon tasks and continue with the (largely) speculative

conversations that we seem to find most comfortable. Or we move the conversation

in other directions entirely.

Anyway, as an old instructional designer, I

admire and welcome the experiential design of Tom's salon here. Actually taking

on the task it poses will likely be a healthy, if humbling,

experience.

Regards,

R. John Howe

Posted by Henry_Sadofsky on 06-01-2003 10:05 PM:

Hi John, and all,

“I admire and welcome the experiential design of

Tom's salon here. Actually taking on the task it poses will likely be a healthy,

if humbling, experience.” You betcha’ …

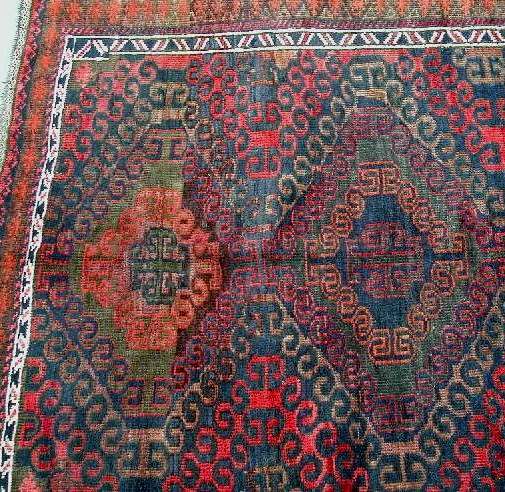

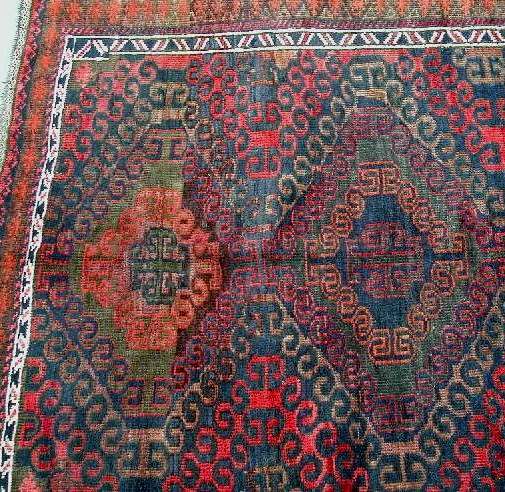

Of the 15 images which precede

the “quiz”, the first (call it “A”) is a detail from a prayer rug (in a private

collection) that was displayed at James Blackmon’s exhibit that coincided with

the Burlingame ACOR. The rug is like no other ‘Baluch’ I have seen, and is, in

my opinion, a most interesting, intriguing, and desirable one. That- in spite of

Tom’s opinion that it is merely “distinctly brown with limited use of colour”.

In fact, it could be argued that what the ‘Baluch’, using a limited

(beautifully rich and glowing) color palette, were able to accomplish in their

weavings, is what is truly remarkable and distinctive about the ‘Baluch’

aesthetic. What is one to make of ‘Baluch’ weavings which have a gay palette but

not the mystery, soulful-ness, “eye-wink” and shimmer of what many think of as

‘Baluch’? Of course, this is not to say that all gaily colored ’Baluch’ pieces

lack these qualities.

Of the following 14 images- the 1st, 5th, 6th,

8th, 10th (call them “B”, “E”, “F”, “H”, “J”) are reminiscent (and perhaps, in

some cases, identical to) pieces that have appeared on e-bay over the past 3

years. These gaily-colored pieces are certainly of a different aesthetic than

what Boucher thought a “Baluchi” should look like. He, rather, would almost

certainly have considered them to be “Baluchi in name only”. As, nowadays, we

are not certain how ‘Baluch’ Boucher’s “Baluchi”s are, nor how non-“Baluchi” his

“… in name only” is- a different classification system would certainly be

welcome.

Tom has proposed that ‘Baluch’ weavings be classified as to

their origin in Khorassan, western Afghanistan, or Seistan. Should available

data make this possible, it would indeed be “a real source of comfort” for both

dealers and collectors. More importantly, such a framework could clarify methods

and avenues for further research.

Before discussing the next grouping of

images in Tom’s presentation it should be pointed out that the text implies that

images “M” and “N” are reversed.

On to the quiz ... I am pretty sure that

I would like #s 7, and 10. I cannot tell enough about #s 1, 2, 8, and 12 (from

the images provided) to form an impression. I suspect that I would feel not

particularly disposed to #s 5, 9, and 11. I am pretty sure that I would dislike

#s 3, 4, 6, and 9. I would also note that the quiz does not include an appealing

image of a “classic” ‘Baluch’ (i.e. perhaps what #12 is meant to represent).

Where are the pieces from? I do not know. I do know, at least for some

of them, where some authorities think they are from. Tellingly, there does not

seem to be consensus amongst these authorities (both current and past). This

raises the question as to which authority one might rely on? The answer to that

is, I believe, simple and straightforward. One may rely on the authority that

presents sufficient data, and data analysis, such as to convince one of the

integrity of the data and the conclusions drawn from it.

In the “Color!”

thread Tom responded to an inquiry of Chuck Wagner’s regarding one of Chuck’s

rugs with: “The muted palette suggest NW Afghanistan rather than NE Persia,

somehow” We might agree that neither “muted palette” nor “somehow” is either

precise or convincing.

About some of the other pieces Tom has

authoritatively replied:

“#10 IS a w. Afghanistan weaving

…”

“Number 2 is not Khorassan... too diverse of a palette… “

“The

latch hook design seen in #7 is a CLASSIC Seistan region rug… As is #3, another

classic pattern seen in Seistan.”

I am hoping that at some point in this

Salon Tom will share with us the data/observations that allow him to reach these

conclusions.

Posted by Henry Sadovsky on 06-01-2003 10:18 PM:

Addendum:

I forgot to point out that Tom's proposed classification system is logically

flawed. Khorassan and Seistan are names which stem from two thousand years ago,

whereas Afghanistan is a modern creation. The problem is that these areas are

not distinct. Part of western "Afghanistan" is contained in "Khorassan" (Herat

was the capital of Khorassan), and part is contained in "Seistan".

Logically consistent alternatives include:

a) NE Iran, NW

Afghanistan, and SW Afghanistan. The problem with this is that it does not

include SE Iran, or W. Pakistan.

b) Western Khorassan, Eastern Khorassan,

and Seistan. The problem with this is that it is archaic.

Of these two

alternatives, I prefer "b" as it is the more inclusive one.

Posted by Steve Price on 06-02-2003 06:48 AM:

I apologize

Hi People

A few messages up, you'll see one from "Henry_Sadofsky". The

name includes a typographical error I made when posting it for Henry Sadovsky. I

apologize to Henry for this.

Regards,

Steve Price

Posted by Tom Cole on 06-03-2003 11:36 AM:

Henry:

You have written-----

“In the “Color!” thread Tom responded to

an inquiry of Chuck Wagner’s regarding one of Chuck’s rugs with: “The muted

palette suggest NW Afghanistan rather than NE Persia, somehow” We might agree

that neither “muted palette” nor “somehow” is either precise or convincing.”

----

I agree with you. Obviously I was not pretending to be precise or

convincing. But if you want to pin me down. I will suppose that rug is from

Afghanistan. I am accustomed to observing a more saturated palette in Khorassan

weavings (palette is a product of provenance) and this piece pictured by Chuck

appears to exhibit characteristics of Afghan work. But now Chuck has informed us

the rug is symmetric knotted… which leaves me totally in the dark.. no opinion

at all. The symmetric knotted Baluch rugs are not within my field of knowledge

at all. There are exceptions to every rule and I am just guessing, not etching

my thoughts in stone as irrefutable facts.

You continue

----

“About some of the other pieces Tom has authoritatively replied:

“#10

IS a w. Afghanistan weaving …”

“Number 2 is not Khorassan... too diverse of a

palette… “

“The latch hook design seen in #7 is a CLASSIC Seistan region rug…

As is #3, another classic pattern seen in Seistan.”

I am hoping that at

some point in this Salon Tom will share with us the data/observations that allow

him to reach these conclusions.”

Let me offer some data/observations

which allow me to reach these conclusions -

Re: #10. The coarser weave (you

have not had the opportunity to see the back), the border system (again not seen

here) and the handle, end finish on the flatwoven closures, all suggest an

Afghan provenance. And I originally purchased it in Afghanistan, many years ago,

in a village in western Afghanistan from the people whose ancestors had actually

woven it. So I hope that clarifies matters for you.

Re: #2… again you

have not seen the entire piece. It is a detail from a khorjin which exhibits the

distinctive knotted pile ‘shoulders’ which connect the two pile bags, shoulders

of a continuous border design in pile. A feature ONLY seen in khorjin (donkey

bags) from Seistan. And, to my knowledge, in my experience, there are no

Khorassan weavings with this type of colour, with such a clear aubergine ground,

with green and that type of orange/red.

Re: #7, please refer to Rugs of

the Wandering Baluch for a similar example, plate 37. These rugs are from

Seistan region. How do I know? Because I have purchased them on the other side

of the border in Pakistan from traders who have brought them from houses in

villages located in Seistan. The traders bought them from the people whose

families had woven them in Seistan, from people who had always lived in Seistan.

These “main rugs” appear in the same long rug format, a main rug format that is

not seen elsewhere in Baluch rugs (rectangular or square shaped main rugs are

more common among the other groups). Why are their carpets this shape? The

weavers are a sedentary people who live in elongated mud houses; the rugs are

made to mimic the shape of their rooms. How do I know this? Murray Eiland, who

has traveled in Seistan told me of the shape of their houses as did Jerry

Anderson, privately, subsequent to the interview in HALI 76 in response to this

very query.

Same goes for #3. I have the same experience with pieces like

this as I have had with similarly patterned rugs as featured in #7, purchased

them from traders arriving from Seistan. In HALI 76, the interview with Jerry

Anderson, for all the unanswered questions it poses, it unequivocally carries an

air of authority. This is a man who traveled thoughout these areas and knows the

language, the people and the rugs. Rugs of this type, with this structure

(asymmetric knot open to the left), palette and design type were identified by

Jerry as rugs originally from the Seisan region of SE Persia. My own field

experience with traders bringing rugs from Persia supports this hypothesis as

well.

Regarding geographical names… we can indulge ourselves in

semantics, or we can just assume we agree about what we are all talking and take

it from there. Afghanistan is a somewhat modern creation in its PRESENT

political form, but there has always been a distinction between Persia and

Afghanistan as their languages, Dari and Farsi, while obviously related, are

different. And when one crosses the modern political border into Persia, the

dialect spoken changes.

Additionally, we can examine some old

travelogues and look for data that will support the geographic identifications

offered here.

While some of the borders of present day Afghanistan are

“modern” (ie. the Durand Line drawn on the eastern border, separating

Afghanistan from India in the latter part of the 19th century), Afghanistan has

existed as an entity, which includes some of the regions from which “Baluch”

rugs originate, for a long time. There is a book published in 1815 entitled, “An

Account of The Kingdom of Caubul" by Montstuart Elphinstone. He speaks of the

“Eimauks and Hazaurehs ….[who]… inhabit the Paropamisan Mountains between Caubul

and Heraut, having Uzbeks on their north and the Dooruanees [Pashtoon] and

Ghiljies [another Pashtoon tribe] on their south.” Elphinstone continues, “One

is surprised to find within the limits of Afghaunistaun, and that very part of

it which is said to be the original seat of the Afghauns, a people differing

entirely from that nation in appearance, language, and manners. The wonder seems

at first removed, when we find that they bear a resemblance to their Toorkee

neighbors, but points of difference occur even there, which leave us in more

perplexity than before. The people themselves afford us no aid in removing this

obscurity, for they have no account of their own origin; nor does their

language, which is a dialect of Persian, afford any clue by which we might

discover the race from which they sprung. Their features, however refer them at

once to the Tartar stock, and a tradition declares them to be the offspring of

the Moguls [Mongols?]. They are, indeed, frequently called by the name of Mogols

to this day, and they are often confounded with the Mogols and Chagatyes who

still reside in the neighborhood of Heraut. They themselves acknowledge their

affinity to those tribes as well as to the Calumuks now settled in Caubul, and

they intermarry with both of those nations. They do not, however, understand the

language of the Mogols of Heraut.”

Some interesting observations noted here,

no? Clearly this region east of Heraut was considered to be in the Kingdom of

Caubul [Kabul] at that time and it is a region that is certainly thought to be

an area from where some of the so-called Baluch weavings of Afghanistan

originate.

Regarding the history of Heraut and its relevance to studies

of Afghanistan, Elphinstone continues in his narrative. “[Heraut] gave its name

to an extensive province at the time of the expedition of Alexander, and it was

for a long time the capital of the empire, which was transmitted by Tamerlane to

his sons. From the house of Timour, it passed to the Suffavees of Perisia, from

whom it was taken by the Dooraunees [Pashtoons of Afghanistan] in 1715. It was

retaken by Naudir Shauh in 1731, and it fell into the hands of Ahmed Shauh in

1749 since which time it has been held by the Dooraunees.” I think we can safely

say that Heraut was considered a part of the political entitiy of Afghanistan as

it was recognized in the mid 18th century. Thus, calling it east Khorassan may

not be completely accurate, but we do all know what you are talking about,

splitting hairs is not necessary.

Henry.. you also wrote, “These

gaily-colored pieces are certainly of a different aesthetic than what Boucher

thought a “Baluchi” should look like. He, rather, would almost certainly have

considered them to be “Baluchi in name only”. As, nowadays, we are not certain

how ‘Baluch’ Boucher’s “Baluchi”s are, nor how non-“Baluchi” his “… in name

only” is- a different classification system would certainly be

welcome.”

Boucher lifted the phrase “in name only” from Michael

Craycraft’s “Baluch Prayer Rugs”, a moniker misattributed to the Colonel.

Michael’s most memorable observation, in my mind, on Baluch rugs and the maze of

attributions, etc. was to say these rugs are made in a “Baluch style”, which

includes Boucher’s Baluch and ‘in name only’ Baluch weavings. That is to say

they have a similar handle, wool quality, etc that identify them as having

emerged from a similar cultural mileau. The tribal names which inhabit the

Baluch nomenclature are real names of real tribes. But it is extremely difficult

to say which tribe wove which rugs as the data for that presumption is certainly

lacking, or at best, indefinite.

On the contrary, with Turkmen studies,

the history of the Turkmen is much more documented than that of the “Baluch” and

early travelers remarked upon the appearance of certain tribes in specific

areas. And thanks to the Russian explorers, ie. Dudin and other documents in

Russian museums with which very few have ever had direct access (at least very

few of us here in the western countries outside of Russia), specific rugs DO

have specific tribal attributions associated with them. The Turkmen tribes first

appeared in historical chronicles at an early date (14th century?). The Seljuks

of Anatolia are descended from the Turkmen and the interest in and impact of the

Seljuks on art in Anatolia and Central Asia is great. The Turkmen aesthetic is a

classical tribal art (if those two terms can be used in juxtaposition), while it

is still unclear what the aesthetic of Baluch rugs should be termed or is

viewed. Hence, the market uncertainty. It used to be that Baluch rugs were given

away free by dealers to their clients, thought to be derivative art and

irrelevant in the long run. The efforts to classify, identify, attribute, etc is

an exercise in establishing a legitimacy to these rugs. We yearn for stories in

the west, usually unable to simply believe our eyes as to what is art and

letting the artistic merits justify our evaluation of that rug (intellectual,

artistic and economic evaluation). In Afghanistan, as noted by Andrew Hale in

HALI 76, the story is free. The rugs aren’t, at least not these

days.

Additionally, the real Baluch of Baluchistan are not supposed to be

engaged in pile weaving, but instead concentrated their efforts on flat weaves.

They are not even called Baluch, but rather go by the name ‘Brahui’ It becomes

increasingly clear the name “Baluch” is somewhat meaningless in the context of

tribal attributions for rugs, but is extremely useful in terms of knowing what

‘style’ of rug it is about which we are discussing.

Posted by Henry Sadovsky on 06-03-2003 04:47 PM:

Geography and history of Khorassan and Seistan

HI Tom. I am most interested to explore these issues further with you and the

group. First, to assure that all start off "from the same page", I offer the

following texts on the geography and history of Khorassan and Seistan.

From: http://www.irancaravan.com/RPR.htm

quote:

Geographical Position, Khorassan Province

The (Iranian)

province of Khorassan, located in the northeast of Iran is the largest

province of the country; covering one-fifth of the area that is 303.000 sq.

km.(italics added). The townships of this province are Esfarayen,

Bardestan, Bojnurd, Birjand, Taibad, Torbat Jaam, Torbat Heydarieh, Chenaran,

Khaaf, Daregaz, Sabzevar, Sarakhs, Shirvan, Tabas, Ferdows, Fariman, Qaenat,

Quchan, Kashmar, Gonabad, Mashad, Mahbandar and Nayshabur. Mashad being the

capital city, where the shrine of his Holiness Imam Reza (AS) the eighth Imam

of the Shiite sect is situated.

Khorassan Province Position

In

1996 about 6 million people resided in Khorassan of which approximately 56.6%

resided in urban areas and 43.3% in rural sectors, the remaining were

non-residents. This province can be divided into two sections regarding its

natural features: The northern section which has a mountainous terrain, though

its lower plains are suitable for agricultural purpose and animal husbandry

.The southern section comprises of low hills and plains with poor vegetation.

Climate, Khorassan Province

Climatically this province is

variable in weather. Located in a north temperate zone, the temperature

increases from north to south but the annual rainfall decreases. For example

Aladaq and Binalood heights experience cold and mountainous weather, whereas

in some parts of Mashad a temperate, mountainous climate exists. Qaenat and

mountain side areas have a mild, semi-arid climate while the southern zones

are warm, dry and arid.

History and Culture, Khorassan Province

In the past history of Iran, the province of Khorassan has been a

constant witness to the rise and fall of powers and governments. Various

classes such as the Arabs, Turks, Mongols, Turkemen and Afqans have accounted

for much unaccountable events in this wide territory. The ancient geographers

of Iran had devided Iran (Iran Shahr) into eight segments, of which the most

flourishing and largest was territory of Khorassan. During the Sassanian

Dynasty the province was governed by a Espahbod (Lieutenant General) called

"Padgoosban" and four margraves, each commander of one of the four parts of

the province.

Khorassan was divided into four parts during the

Islamic period and each section was named after the four large cities, such as

Nayshabur, Marve, Harat and Balkh. In the year 31 AH, the Arabs came to

Khorassan and it was at this time that the inhabitants accepted the religion

of Islam. Till the year 205 AH, this territory was in the hands of the

Bani-Abbas clan, followed by the rule of the Taherian clan in the year 283 AH,

and there after in 287 AH the Samanian Dynasty came to the scene as rulers.

Sultan Mohmood Qaznavi conquered Khorassan in 384 AH and in the year 429 AH

Toqrol, the first of the Saljuqian Dynasty conquered Nayshabur.

Mahmood Qaznavi retaliated against the invaders several times, and

finally the Qaznavi Turks defeated Soltan Sanjar Saljuqi. But there was more

to come, as in the year 552 AH. Khorassan was conquered by Kharazm Shahian and

because of simultaneous attacks by the Mongols, Khorassan was annexed to the

territories of the Mongol Ilkhanan. In the (8th century AH, a flag of

independence was hoisted by the Sarbedaran movement in Sabzevar and in the

year 873 AH, Khorassan came into the hands of Amir Teimoor Goorkani and the

city of Harat was declared as capital. In the year 913 AH Khorassan was

occupied by the Ozbekans.

After the death of Nader Shah Afshar in 1160

AH, Khorassan was occupied by the Afqans. During Qajar period, Britain

supported Afqans as they were responsible for guarding the Indian Borders.

Finally, the Paris Treaty was concluded (1903) and Iran was compelled not

to interfere in the internal affairs of Afqanistan. At this time Khorassan was

divided into two: the eastern part, which was the most densely populated

region came under Britain’s protection, and the other western section remained

under the occupation of Iran.

From: http://www.iras.ucalgary.ca/~volk/sylvia/Seistan.htm

The

Vanished Paradise of Seistan

Quoted from:

George Curzon,

Persia and the Persian Question, vol 1 (1892)

quote:

The derivation of the name Seistan or Sejestan from Sagastan, the country of

the Sagan, or Sacae, has, says Sir H. Rawlinson, never been doubted by any

writer of credit, either Arab or Persian ; although it is curious that a band

of roving nomads, as were these Scythians, who descended hither from the north

in the third century A.D., should have bequeathed a permanent designation to a

country which they only occupied for a hundred years. (Some English writers,

however, have derived it from saghes, a wood that is grown locally and is used

as fuel by the Persians.) Expelled by the Sassanian monarch Varahran II (A.D.

275 -292) they have long vanished from history themselves; but in the name of

the district they may claim a monumentum oare perennius.

At different

epochs of history territories of very differing sizes have been called

Seistan, according as the dominion of their rulers has been extended or

curtailed. In its stricter application, however, the name has always been

peculiar to the great lacustrine basin that receives the confluent waters of

the Helmund and other rivers, whose channels converge at this point upon a

depression in the land's surface, with very clearly defined borders, and a

length from north to south of nearly 250 miles. It is certain that in olden

days this depression was filled by the waters of a great lake; and, were all

the artificial canals and irrigation channels, by which the river-contents are

now reduced and exhausted, to be destroyed, I imagine that it would very soon

relapse into its primeval conditions.

The modern Seistan may be said

to comprise three main depressions, which, according to the season of the year

and the extent of the spring floods, are converted alternately into lakes,

swamps, or dry land. The first of these depressions consists of the twofold

lagoon formed by the Harut Rud and the Farrah Rud flowing from the north, and

by the Helmund and the Khash or Khushk Rud flowing from the south and east

respectively. These two lakes or pools are connected by a thick reedbed called

the Naizar, which, according to the amount of water that they contain, is

either a marsh or a cane-brake. In flood time these two lakes, ordinarily

distinct, unite their waters, and the conjoint inundation pours over the

Naizar into the second great depression, known by the generic title of Hamun

or Expanse, which stretches southwards like a vast shallow trough for many

miles. When the British Commissioners were here in 1872, the Hamun was quite

dry, and they marched to and fro across its bed. But in 1885-6, when some of

the members of the later Russo-Afghan Boundary Commission were proceeding this

way from Quetta to the confines of Herat, it was found to be an immense lake,

extending for miles, with the Kuh-i-Khwajah, a wellknown mountain and

conspicuous landmark usually regarded as its western limit, standing up like

an island in the middle. In times of abnormal flood the Hamun will itself

overflow; and on such occasions the water, draining southwards through the

SaTshela ravine, inundates the third of the great depressions to which I

alluded, and which is known as the Zirreh Marsh. This was said at the time of

the Commission not to have occurred within living memory, it being a far more

common experience to find all the river-beds exhausted than all the lake-beds

full ; and the Zirreh as a rule presents the familiar appearance of a salt

desert. In 1885, however, a British officer exploring Western Beluchistan

found water two feet deep flowing down the Sarshela or Shela, and forming an

extensive Hamun in the northern part of the Zirreh, which was said to be over

one hundred miles in circumference.

It will readily be understood from

the above description how variable is the face of Seistan, and what a puzzle

to writers its Protean comparative geography becomes. For not only do the

lakes alternately swell, recede, and disappear - the area of displacement

covering an extent, according to Rawlinson, of one hundred miles in length by

fifty miles in width - but the rivers also are constantly shifting their beds,

sometimes taking a sudden fancy for what has hitherto been an artificial

canal, but which they soon succeed in converting into a very good imitation of

a natural channel, in order to perplex some geographer of the future. It is

not surprising, therefore, that while the country owes to the abundant

alluvium thus promiscuously showered upon it its store of wealth and

fertility, it also contains more ruined cities and habitations than are

perhaps to be found within a similar space of ground anywhere in the world.

Such in brief outline is the physical conformation of Seistan. I will

now proceed to its history. From the earliest times there has been something

in Seistan that appealed vividly to the Persian imagination. The country was

called Nimroz, from a supposed connection with Nimrod, 'the mighty hunter'; it

was the residence of Jamshid, and the legendary birthplace of the great

Rustam, son of Zal, and fifth in descent from Jamshid. King Arthur does not

play as great a part in British legend as does the heroic Rustam in the myths

of Iran. For, after all, Arthur was a mortal man (and, if we are to follow

Tennyson, almost a nineteenth century gentleman), while Rustam fought with

demons and jinns as well as against the pagan hordes of Turan and Afrasiab.

Perhaps our Saint George of the Dragon would be a nearer parallel; and just as

we stamp the record of his matchless daring upon our coinage, so do the

Persians emblazon the great feats of Rustam upon gateway and door and pillar.

Seistan emerges into the clearer light of ascertained history in the

time of Alexander the Great, when it was known as Drangiana (identical with

the land of the Herodotean Sarangians). He probably passed this way on his

march eastwards to India; whilst on his return therefrom, though he pursued a

more southerly line himself, through Gedrosia (Mekran) to Carmania (Kerman),

he despatched a light column under Craterus through Arachotia and Drangiana.

Under the Sassanian monarchs Seistan was a flourishing centre of the

Zoroastrian worship, and hither came the last sovereign of that dynasty,

Yezdijird, flying from the victorious Arabs on his way to his fate at Aferv.

It was under the succeeding regime that the province attained the climax of

its material prosperity; and to this-the Arab-period are to be attributed the

vast ruins of which I have previously spoken. In the ninth century a native

dynasty known as the Sufari or Coppersmiths, was founded by one Yakub bin

Leitb, a potter and a robber, but a soldier and a statesman who won by arms a

shortlived empire that stretched from Shiraz to Kabul, but collapsed before

the iron onset of Mabmud of Ghuzni in the succeeding century. El Istakhri,

visiting Seistan at this epoch, described it as a country of populous cities,

abundant canals, and great wealth; among its natural resources being included

a rich gold mine that subsequently disappeared in an earthquake. In the

thirteenth and fourteenth centuries Seistan, like most of its neighbours,

experienced the two successive visitations of those scourges of mankind,

Jenghiz Khan and Timur Beg, being turned from a smiling oasis into a ruinous

waste, and suffering a murderous blow from which it has never recovered. The

Sefavi dynasty repeopled it under the local rule of the ancient reigning

family of Kaiani, who claimed descent from Kai Kobad, the first Achaemenian

king. But the march of time brought round the fated cycle of injury and

desolation; and at the bands both of the Afghan invaders of 1722, and of Nadir

Shah who expelled them, it completed its chronic tale of suffering. Remaining

a portion of the mighty empire of the Afshar usurper till his death in 1747,

it then passed to the sceptre of Ahmed Shah Abdali, the adventurous captain

who, imitating his master's exploits, rode off and founded the Durani empire

in Afghanistan. From this epoch dates its appearance on the stage of modern

politics, and during the last thirty years upon the chess-board of

Anglo-Indian diplomacy . . .

Posted by Henry Sadovsky on 06-03-2003 07:07 PM:

Geography

Tom- you said: "Regarding geographical names… we can indulge ourselves in

semantics, or we can just assume we agree about what we are all talking and take

it from there." To be clear, you are refering to alternatives on how to

distinctly divide the large area of 'Baluch' weaving (more on that later) into

three regions.

Three possibilities have been presented here:

-

Khorassan/W. Afghanistan/Seistan

- N.E. Iran/N.W. Afghanistan/S.W.

Afghanistan

- W. Khorassan/E. Khorassan/Seistan.

I disagree with your

characterization of this aspect of the problem as a semantic one. This is a

matter of geography. Objective facts are readily available to clarify the issue.

I see no justification (such as might be the case if a particular scheme was

traditional or commonly accepted) that would warrant perpetuation of a flawed

choice.

Posted by Tom Cole on 06-03-2003 10:18 PM:

You may call an area that was never 'ruled' by anyone, much less those in

Herat by the name East Khorassan. I do not care.. it is all semantics to me...

names on a map are semantics.. the geography is unchanged as is the history.

That area where these rug weaving groups live/lived is what it is... w.

Afghanistan or E. Khorassan... take your choice... it does not change the

landscape of Baluch studies very much.

Posted by Henry Sadovsky on 06-04-2003 02:38 AM:

A desert landscape?

Hi Tom. The geography issue is rather clear to my mind and I will not press

the point further. As for "the landscape of Baluch studies", all are free to

decide whether it is parched or fecund.

You wrote:

quote:

"Boucher lifted the phrase 'in name only' from Michael Craycraft’s “Baluch

Prayer Rugs”, a moniker misattributed to the Colonel. Michael’s most memorable

observation, in my mind, on Baluch rugs and the maze of attributions, etc. was

to say these rugs are made in a “Baluch style”, which includes Boucher’s

Baluch and ‘in name only’ Baluch weavings.

Interesting... My quick review of "Belouch Prayer Rugs" did

not locate this phrase ("in name only") or concept ("Baluch Style"). In fact,

Michael wrote (in the Introduction): "Anybody who has observed many Belouchi

weavings is soon overwhelmed by the lack of any cohesive unity in style,

design and method of end finishing."

Nevertheless, it is certainly the

current paradigm (yes I have read Kuhn's book) that there exists a large body of

piled weavings which, while not the products of Baluch peoples, nonetheless

follow closely the Baluch tradition. Hence, Azadi's title: "Carpets in the

Baluch tradition".

I daresay that titling this Salon “Baluch aesthetics”,

as well as the following two quotes, has not diminished the confusion which is

present in the landscape of Baluch studies. You wrote:

quote:

Additionally, the real Baluch of Baluchistan are not supposed to be

engaged in pile weaving, but instead concentrated their efforts on flat

weaves. They (i.e. the real Baluch) are not even called

Baluch, but rather go by the name ‘Brahui’ (emphasis and italics added).

Baluch vs. 'Baluch'? Merely semantics?

I quote you

again Tom:

quote:

It becomes increasingly clear the name “Baluch” is somewhat

meaningless in the context of tribal attributions for rugs, but is extremely

useful in terms of knowing what ‘style’ of rug it is about which we are

discussing.

I believe that analysis of this last statement is needed,

but I am now going to bed.

Posted by Steve Price on 06-04-2003 06:10 AM:

I say Germany, they sayDeutschland

Hi Tom,

Your wrote, They (i.e. the real Baluch) are not even called

Baluch, but rather go by the name ‘Brahui’.

This isn't critical to

any of your major points, of course, but before anyone takes off running with

this as a subtopic I would like to point out that what we call people and what

they call themselves is seldom the same.

The only modification I'd make

in your sentence is to leave out the word "even", which implies that there

something bizarre about us calling them Baluch. It's far less peculiar than us

calling the Deutsch "Germans", or the French calling the Nihonjin

"Japonaise".

Regards,

Steve Price

Posted by Tom Cole on 06-04-2003 09:35 AM:

Henry.. sorry.. the 'in name only' moniker was from the associated

exhibition, and guess it never made it into the catalogue.. but in any case it

was a phrase Michael used early and often to which proper credit is

due.

And regarding clarification of a Baluch "style" of weaving....I

wrote, "these rugs are made in a “Baluch style”, which includes Boucher’s Baluch

and ‘in name only’ Baluch weavings. That is to say they have a similar handle,

wool quality, etc that identify them as having emerged from a similar cultural

mileau."

Seems pretty clear.. it is again, as I stated, a phrase or

concept coined by Michael Craycraft, and seems very useful in that it opens the

door for eliminating endless theories concerning specific tribal attributions,

some of which may be impossible to determine.

Perhaps my approach is

inevitably flawed... I am not so concerned with exactly who wove what , but

prefer looking at them and judging them on their artistic merits, a simplistic

approach I guess. For those with a more mathematical, analytical methodology, I

am guessing what I write is rather uninteresting and possibly irrelevant.

Posted by Steve Price on 06-04-2003 10:00 AM:

Hi Tom,

Your wrote, Perhaps my approach is inevitably flawed... I

am not so concerned with exactly who wove what , but prefer looking at them and

judging them on their artistic merits, a simplistic approach I guess. For those

with a more mathematical, analytical methodology, I am guessing what I write is

rather uninteresting and possibly irrelevant.

I'd say that every

approach is inevitably flawed in the real world, but that doesn't make any of

them uninteresting or irrelevant. I believe one of the strengths of the format

we use here is that it brings many approaches to bear on the issues. We learn

from each other through our interactions, and I think most of us broaden and

sharpen (a difficult combination to achieve!) the way we think about rugs and

textiles in the process.

Regards,

Steve Price

Posted by Chuck Wagner on 06-04-2003 11:12 AM:

Baggage

Hi Tom,

If I read your previous post correctly, the photos below

should be of a Sistan va Baluchistan donkey bag. This is what you mean by piled

shoulders, right ?:

It

has highlights in a strange pinkish orange that looks synthetic, but, on the

pleasant side of synthetic. The green in the closeup is uncomplicated and

probably synthetic as well (it doesn't look like a yellow-over-blue job). But at

the other end of the bag it's a more variegated olive tone; a different batch of

wool, and maybe an overdye.

I understand where you're trying to go (I

think) by abstracting to the provincial or regional level. Dick Parsons also

groups Baluch and Baluch-type weavings in the same chapter of his book, with

equal emphasis on geography and tribal association. Tribal attributions ARE

often quite tenuous. But Sistan va Baluchistan probably contains 80% of the

Baluchis in Iran. There must be some variations in color/design/weave that can

be classified further and at a lower level, within the "greater Sistan"

category.

It would be helpful if you elaborated a little more on how you

go about classifying Baluch-type weavings. You mentioned in the Salon that you

use color as the primary criterion for provenance SOME pieces, but you didn't

really explain how you see the "whole world" of Baluch-type weavings and how you

decide which go into the "color bin". A brief note was made of iconography and

weave, but more should be said (I think). I think we'd all benefit from an

overview of your broader perspective, and how & when color becomes the

dominant factor.

Regards,

Chuck

__________________

Chuck

Wagner

Posted by Henry Sadovsky on 06-04-2003 12:00 PM:

For two points:

Baluch/Brahui, German/?

a) Deutschlander

b)

German-American

c) Spaniard

d) Maori

Posted by Tom Cole on 06-04-2003 12:13 PM:

Chuck- You are right, your khorjin is from Seistan, as the pile 'shoulders'

are a distinctive Seistan Baluch feature. You are also correct that within

Seistan itself, some differences in palette and design occur that seem to be

suggest different groups. For example, there is a corroded blue dye that occurs

in some weavings, not all from Seistan, and it is a colour that, in my

experience, is confined ONLY to this area as I have not seen it in Khorassan

weavings.

Regarding all the criterion by which one might use to judge

all the divisions, etc. between the rugs, it is complex. Some of it is based on

structure, ie. the reason I stated all the rugs in the "quiz" were asymmetric

knotted open left. Which is why YOUR rug with symmetric knots is confusing to

me. So, often it is based on a variety of factors including colour, structure,

design, etc. In this forum, as in HALI 97, I tried to simplify things... more so

than what will withstand the closest and most sceptical scrutiny. For example,

the colour issue is clouded by related groups inhabiting different regions,

sharing similar colour sensibilities, but with different formats and patterning

(ie. Chakhansur and Seistan, two different areas with related aesthetics in

terms of colour and some motifs). The main rug format in Chakhansur is NOT the

long rug format of Seistan, but they will often share some designs (ie. latch

hook 'mushwani' medallions) and both will tend towards a more colourful palette

than that used in Khorassan.

Posted by Sophia Gates on 06-04-2003 02:10 PM:

Seeking Answers, We Find Questions!

Chuck, Henry, Tom, et. al.,

Whoa. I think I've already learned more

about this region and these weavings than I'd previously known.

So -

therefore I now know considerably LESS than I did a few hours ago - if that

makes sense -

Some questions:

1. Wouldn't it be helpful for people

who have some of these Seistan - and other non-typical "Baluch" pieces to start

analyzing them structurally, then perhaps we could pool our resources and see if

we can come up with a database?

2. I don't think we can discuss color

and ignore design. The Seistan pieces seem to have different design ideas from

the Khorossan pieces. I had a classic prayer tree piece, for example, with a

camel ground - classic Baluch piece - finely woven, camel/red/blue - I sold it

but I have pix which I might send to Steve later once I've secured permission

from the new owner. In the meantime, I think everybody knows what I'm

discussing.

I also have 3 Seistan region pieces, two I got from Tom and

one locally - two are balishts and one is a bag like Chuck's. They obviously

come from a completely different design pool than the prayer rug - AND their

color is different. They feel different too - longer pile, so forth.

Structurally they aren't the same at all!

I am beginning to think we

should not even be classifying these things as Baluch - we do need - sorry! - to

try to figure out who these folks were/are!

3. I'm curious, of course,

WHY things evolve as they do. So - question for the historians: do we know to

what extent the people in these various areas relied upon the services of

professional dye masters? Regardless of familial or tribal affiliations, it

strikes me that people in various areas might have had different habits

regarding the use of professionally dyed yarns. Local fashion might have played

a role in color choice also. But, I think this is something that could be

researched - in fact, probably is long overdue: the history and economic and

artistic impact of the dye masters on the tribal/village rugs in Iran and along

the path of the Silk Road.

I've been told this was primarily a Jewish

trade. So, perhaps there are resources available, not necessarily in the history

of rugs, but in Jewish historical sources.

I can't help but come to the

hypothesis that the more gaily color "Baluches" might have been made by people

with access to professional dye shops. Although I personally find the more

subdued Baluch pieces very beautiful, and appreciate them also for their very

subtle intricacies of design, I like the somewhat coarser yet more "colorful"

Seistan pieces as well. And those colors strike me as presenting a challenge to

the people making them.

Thanks in advance to all,

Sophia

PS: on

the topic of esthetics: I think it's natural for the weavers of the more

intricate, finely woven Khorossan pieces to have chosen a more subtle palette.

That way the drawing wouldn't be overwhelmed by the color. Also, one has to

assume they made a choice, a conscious decision, not to use more "gay" color -

perhaps they found it unsuitable for what they were trying to express. The

limiting factor, of course, would have been their access or lack thereof to

professional dye masters. On the other hand, perhaps they DID buy professionally

dyed wool and rejected the bright colors on purpose.

In other words,

bright colors are not necessarily BETTER colors. Color has such a tremendous

impact emotionally, people wanting to express other ideas, more sombre thoughts,

mathematical intricacies, etc - which do show up in the more subtle Baluch

weavings - will automatically and deliberately choose more sombre colors.

Posted by Henry Sadovsky on 06-04-2003 06:21 PM:

Soul

Hi Sophia. You are so sensible and you write so beautifully. I was just

thinking:

- If you are between 18 and 65 y.o.

- Not currently

betrothed

- Willing to relocate to Utah, while,

- I convince my only

current wife to do the same,

then maybe we should talk

privately.

With regard to your questions:

1. Yes! An excellent

example of this type of effort is what Bob Pittenger has done with regard to

Blue-ground prayer rugs. Until the method yields sufficient data as to allow a

consensus on specific points of provenance/attribution, it would be most logical

to start with a purely descriptive category of the items that were to be further

analyzed. For example, one such effort could be directed to "gaily colored pile

weavings in the 'Baluch' tradition".

2. Agreed. A fairly safe prediction

is that with such an effort as you describe one would end up wondering why they

ever thought the different groups were of the same family. As you have noted,

different groups of 'Baluch' weavings can differ in wool, pile, design pool,

color, weave (and, I would add: hand, handle, and emotional

temperature/sensibility/impact). This is what Michael Craycraft was getting at

in the statement from the Intro of "Belouch Payer Rugs" I quoted earlier. As you

probably know, Michael rarely sees Baluch pieces (note absence of quotation

marks)!

3. Pass

Note to your P.S

My intuition (FWIW) suggests

to me that the choice of a limited, "somber" (it is nothing of the sort to me)

palette in "classic"/red-and-blue/Boucher-type 'Baluch' weavings was a very

basic and deep one.

I agree totally that "bright colors are not

necessarily BETTER colors." The color of really good "classic 'Baluch' weavings

is unsurpassed to my eye. I cannot say that I get the same sense of awe from

even the best "gay" 'Baluchs'.

Posted by Sophia Gates on 06-05-2003 12:33 PM:

A Passion For Color

Dear Henry,

May I bring my cats?

Sigh. Back to Intellectual Matters:

I agree totally with Henry about the deep colors, the dignity of the "classic"

Baluches. I think they're marvelous. And, I believe they represent a completely

different idea of color and design than the gaily colored pieces - not the

result of having forgotten how to make bright colors - or "lateness" - but the

result of many deliberate choices resulting in a restrained, elegant, classical

esthetic.

So with these other textiles, it seems we have another idea - a

different sort of expression. Tom, if possible could we please see the whole

pieces? Whereas the fragments show color, they don't show the entire design -

and as I said above, I think it's important that we understand the

interrelationship of color with the other elements of design.

And - who,

ahem, wants to start keeping a database of structural information? We already

have a start!

As for the information concerning who these people were or

are - I'm going to poke around the 'net a bit, see if I can hook up with a

university - possibly even in Iran.

One of my hobbies is reading

mysteries. One of my favorite mystery authors is Tony Hillerman, who writes

about my beloved home in the Southwest, and focuses especially on the Dineh -

the Navajo people. In his latest, he has a hilarious passage concerning gold

mines, how the Dineh very carefully directed the belagaani - the white folks -

in exactly the wrong direction when they asked the location of possible gold

deposits. So, I'm sure the information is out there, about who these Seistan

weavers were - but we must seek it through proper channels, so to

speak.

Best to all,

Sophia

Posted by Chuck Wagner on 06-05-2003 05:28 PM:

Department Of Gay Dark Muted Colorful Rugs

Hi Sophia, et all..

First a couple residual images from the Sistan

donkey bag, to partially address your interest in technical structure. This

particular bag is currently on the other side of the planet from me, so I can't

give you the gory details right now. I can say that this piece has a blue-gray

cotton weft.

In this shot of the back, note the heavy ribbed character

and partial knot depression, a characteristic that I often see in Irani Baluchi

products. Afghan Baluchi stuff rarely has any knot depression, in my

experience:

And a shot of the medallion from the other end of the bag

showing a very different green:

In fairness to myself, the color

combinations on this bag are not attractive to me. But it's an unusual piece for

the market here, I like the kilim work at the bag opening, and it looks nice on

a wall, from a distance.

Now, for an Afghani rug with Bipolar

Disorder; call me crazy, but I love this one, despite the fact that it

demonstrates how hard it is to get good photos of carpets. Both film and digital

cameras have different color sensitivity that the human eye, and trying to

either emphasize, or faithfully represent, certain rugs (like THIS one) can be a

real PITA.

.....But

after taking LOTS & LOTS & LOTS of shots I got some that I like...

This piece

addresses several prior talking points:

1) Some rugs that are inside

should really be outside to be appreciated

2) Contrary to the general public

perception, Baluch rugs CAN and DO have colour

3) Green, in older Baluchi

goods, generally sources from the areas peripheral to the Dasht-i-Margo and

Sistan deserts.

4) If Mushwanis wove rugs, what might they look like ?

5)

Bright colors are not necessarily better colors

6) The statement "the OLD

ones from Afghanistan have PLENTY of colour and are never dark, mysterious or

without colour contrast" probably should not contain the word

"never"

And one new talking point:

1) Swamp-edge dwelling

wives of goat-herding drug smugglers have interesting, if not quirky, ideas

about color

The images:

Indoor shot, modest lighting:

Outdoor shot,

overcast sunlight:

A closeup of one corner, in bright sunlight:

A shot of the bottom

end of the rug at a weird angle so the colors could be brought out (more because

of the camera's sensitivities; it looks darker to the naked eye. Indirect

light):

A closeup of the green area, showing the rose/maroon

outlines of the latch hooks (bright sunlight):

An ode to Sophias

structure thing. Haiku:

Knots: 9V x 6H asymmetrical open to the left,

Warp : Ivory wool Z2S

Weft : Brown wool, 2 shoots, each Z

spun

(Note that the pile yarn is quite thin):

And finally, one for Yon. One

bright green knot, the only one in the rug:

Regards,

Chuck

__________________

Chuck

Wagner

Posted by Filiberto Boncompagni on 06-06-2003 04:25 AM:

Chuck and all,

The structure of your Sistan donkey bag is the same of

a modern Iranian Balouch of mine. Same ribbed back, blue-gray cotton weft. Mine

has symmetrical knots.

I spare you the pictures because the rug is in

storage.

I submit to you all, instead, the picture of one I

missed.

It looked like an old Balouch prayer rug, classical floppy

handle, soft and lustrous wool, rather classical tree-of-life design, ends gone,

very reasonable priced…The pastel-pink palette stunned me.

See

why?

Being

accustomed to the dark colors of old Balouchis I suspected a chemical wash, so I

took a picture and decided to think about it overnight.

The day after it was

gone.

Now I saw that Balouch rugs can have different palettes.

At the

moment I‘m beginning to doubt it was chemically washed…

Mournfully,

Filiberto

Posted by Henry Sadovsky on 06-06-2003 03:39 PM:

A rose is a rose is a rose?

Hi Filiberto. Sometimes (mourned) missed opportunities turn out (in

hindsight) to have been (fortuitously) avoided errors in judgement.

The

rug you show seems to me to not be a "real thing". (Tom, was it you who taught

me that phrase)? By that, I mean to say that it does not appear to me to have

been woven with either passion or conviction. It lacks "spark", personality, "a

face". To me, this indicates that it is a late weaving (nothing particualrly

wrong with that) that is detached from the cultural context that "inspired it"

(not the kind of thing that is "collectible"). Just my

opinion...

Provocatively yours,

Henry

Posted by Chuck Wagner on 06-06-2003 03:59 PM:

Filiberto,

In Parsons' book on Afghan rugs, there is a photo of an old

Baluchi rug (plate 93a) with a subtle rosy pink that looks similar to that in

your picture. He explains it as a product of dye oxidation. I think you probably

would have seen color deep in the pile, in the case of a chemical wash.

I have seen one or two rugs that had been completely soaked with salt

water (in one case) and strongly alkaline city water (the second case) and both

had a similar tone in what was left of the red dyes. I presume that these were

acid dyes and were strongly suceptible to an alkaline bath.

And for Tom,

a question:

Are you aware of, and do you have any examples of, flatweaves

that have colors similar to the pile pieces you show in the Salon ?

I have

seen several Baluchi kilims with soft red tones and the usual blues and whites,

but never any of the pastel shades or green. And, of course, the really dark

ones.

Regards,

Chuck

__________________

Chuck

Wagner

Posted by Robert Alimi on 06-06-2003 04:59 PM:

Interesting salon. It seems that most everyone agrees (including Edwards,

Wegner and Boucher) that the only "Baluch" classification scheme that could make

any sense is a regional one. Given the large number of "identified" tribes, and

given that some tribes apparently had no qualms about changing their name (e.g.,

to show allegiance to a new khan), the tribal waters can get pretty darn murky.

A regional approach seems like a good idea. That said, using Wright/Wertime’s

"anchor piece" approach might be a logical next step. Tom mentioned owning some

rugs of known provenance. Are there other candidate "anchor pieces" out

there?

As for palette, I'd agree with those folks who think that the

darker and somewhat limited palettes can be a wonderful thing too. When the wool

and dyes are really excellent, these rugs can be elegant; but it does require

good lighting. I think if you did a survey of ruggies who are extremely

knowledgeable about interior lighting options, you'd find that the most

knowledgeable among them are "Baluch"

collectors!

Regards,

-Bob

Posted by Henry Sadovsky on 06-06-2003 05:16 PM:

Drool, drool...

Hi Chuck. You asked Tom: "Are you aware of, and do you have any examples of,

flatweaves that have colors similar to the pile pieces you show in the Salon"?

That's like asking Jerry Seinfeld if he knows where to get a good corned

beef sandwich. As soon as Tom stops drooling he will have much info for you. :

)

Hi Robert. I like your post very much, and agree with all of it except

for the implication of: "As for palette, I'd agree with those folks who think

that the darker and somewhat limited palettes can be a wonderful thing too".

Not only can they be have a wonderful palette "too"- some may find them

to be unsurpassed (Seljuk carpets excepted).

Posted by Chuck Wagner on 06-07-2003 03:16 PM:

Call 1-800-Provenance

Hi All,

Since we're supposed to be on the subject of "non-dark" Baloch

and Beloutsch-like weavings, I'd like to toss this one out for

comment:

It's

about 10 feet long and 4 feet wide. I'm at a loss to explain this piece; someone

who ought to know says it's Baluchi, maybe dating 1940s to 1950s. Someone else

who ought to know says he thinks it's more like 1920s and is more likely an

unspecified nomadic Afghan transhumant. Both agree that the weaver may have seen

Turkoman weavings at one time, either through a fog or from a great

distance.

The color scheme is simple. I think it's probably a synthetic

red, but I'm uncertain. There is more color at the base of the pile than on top.

It looks like it's seen a lot of sunlight over the years. I guess I would say

the tips look "paler" rather than "faded" (a very subjective characterization, I

admit). The warps are handspun light gray wool (very unusual for Baluchi work),

and the wefts are 2 shoots of handspun brown wool.

The weave does have a "sort of

Baluchi" look to it, asymmetrical open to the left:

And, the weaver had the skills

to handle distortions caused by uneven loom tensions, etc. :

Any ideas

?

Regards,

Chuck

__________________

Chuck

Wagner

Posted by Tom Cole on 06-07-2003 04:19 PM:

Chuck... the rug is a Baluch from w. Afghanistan, something the dealers out

there would call 'Taimani', late as you say, a practical floor rug.

Posted by Vincent Keers on 06-07-2003 08:25 PM:

Cotton

This 1's for John:

It isn't the greatest bagface on earth, but it has "rags" in.

Cotton rags

as you can see. And some strange colours in cotton.

as if she was getting

tired of all the red,brown,blue.

The pink (at the top) isn't faded. It's

front, back and inside pink.

For all,

Dark, pastel or whatever. Don't

think there's a law that dictates anything.

These weavers used everything

they could lay their hands on.

The clean, fixed new pakistan stuff seems to

be more colourful.

"Beloudch" bags, all original, but no mileage to

them.

Did anyone mention Uzbek? The embroideries are veeerrry

colourful.

And because my new camera works so nice, a "pioenroos" from my

garden. No colour.

Best regards,

Vincent

Posted by R. John Howe on 06-08-2003 09:33 AM:

Thanks, Vincent -

Who would have thought it: a Balouch weaver at the

edge of rag rugs. The folks on the "rug talk" board (where they talk SERIOUSLY

about rag rugs, and especially about weaving them) would love

it.

Regards,

R. John Howe

Posted by R. John Howe on 06-22-2003 06:49 PM:

What I Heard and What I Decided

Dear folks -

As the initiator of this thread I need to deliver on a

promise I made when I started it. Please note that as I began this post, I see

that Tom may have provided the "book" answers to his exercise, but I have not

looked at it. Instead, I have simply tried to "brief" his beginning resource

guidance and then to apply it in the task he provided.

Two sorts of

errors at least are possible.

1. That I have not understood properly what

Tom has recommended in his resource.

2. That I have not applied these

rules properly in my decisions and/or in the associated rationales.

One

part at a time.

First, this is what I heard in summary.

I think

Tom has recommended about four or so distinctions with his rules. For me they

are:

1. Khorasan: bright red color. Sometimes orange-red or

magenta.

Afghan rugs from this area have warmer more yellow reds.

2.

Seistan: Greens, brighter blues, camel colored wool. Later pieces can lack

contrast.

3. Arab Balouch: darker, murkier, monochromatic (although a

more generous use of white seems present in one earlier? example)

4.

Doctor-i-gazi: complex but stiff and mechanical drawing (not a color

indication); associated Afghans are "colorful, pretty."

So the first

question is whether I got what Tom said right. I found it hard to take in his

argument at points and so there may be errors.

Now, my indications, using

the rules above.

Rug 1: Khorasan: clear, brilliant red

Rug 2: Seistan:

brown-red, camel color, some green

Rug 3: Seistan: green, brighter

blue

Rug 4: Earlier Arab Balouch: use of white, less monochromatic

Rug 5:

Later Arab Balouch: darker, mechanical

Rug 6: Khorasan: aubergine, clear

orange-red

Rug 7: Seistan: brown-red, green, camel color

Rug 8: Khorasan:

bright, clear red

Rug 9: Seistan: brown-red, camel color

Rug 10: Afghan

Balouch: color palette similar to resource example that was contrasted w/

doctor-i-gazi. Purple-red, medium blue.

Rug 11: Seistan: green, brown-red,

camel color

Rug 12: Khorasan: clear red

Regardless of my score I

should also report that I found Rug 4 and Rug 7 the most difficult to

decide.

Regards,

R. John Howe