Posted by R. John Howe on 03-26-2003 07:23 AM:

Moghan is Shahsevan

Dear folks –

Congratulations to Bertrand Frauenknecht for a very

detailed and interesting historical salon essay.

The Shahsevan are not my

area of interest and I am, in truth, a relative fledgling with regard to rugs in

general, so I need to be permitted to ask questions of great “innocence,” (to

use a polite expression to describe my real condition).

I understand that

there is no guarantee that things will be simple in the rug world and that the

geographic area under discussion is one of considerable ethnic diversity and

that it was contested by Russia and Iran over the years. So there may often not

be clear answers available (ever) in some areas.

But I was struck by Mr.

Frauenknecht’s indications in the following passage:

“..Influences from

neighbouring people surely have changed designs, as we can see that the southern

Shahsevan produce rugs with different designs than those of the northern

Shahsevan. Take the Afshar Bidjar as an example. It is probably a Kurdish rug

originally, but the Afshar Shahsevan who were neighbours there took the design

over and produced the better quality. To stretch my point, we can talk of a

Shahsevan Gendje or a Shahsevan Shirvan. What is now awaiting our understanding

is that the term Shahsevan is comparable to the term Turkmen, and we can start

by accepting that a Moghan rug is a Shahsevan rug…”

My thought:

I

have heard that many of the better Bidjars were made by Afshar rather than Kurd

weavers, but this is the first time I have heard it claimed that in fact the

better “Afshar” Bidjars were likely made by Shahsevan weavers. I wonder how we

know this and how one recognizes such a weaving.

But it is the last

sentence in this paragraph about which I want to inquire most directly. “…we can

start by accepting that a Moghan rug is a Shahsevan rug…”

Mr.

Frauenknecht provides an instance of a rug that he suggests is properly seen as

Shahsevan, and which has field devices often associated with Moghan

weaving.

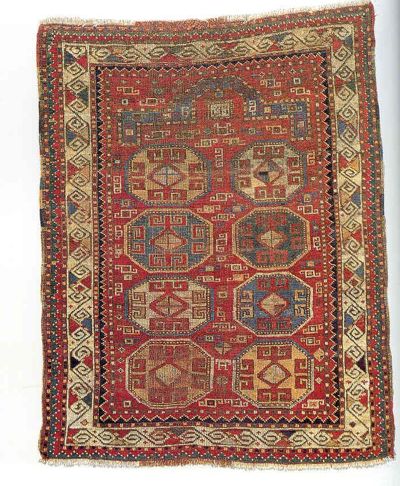

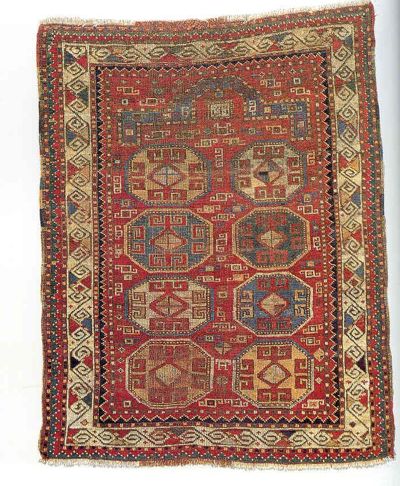

Here, below, is Plate 37 from Kaffel’s “Caucasian Prayer Rugs,”

which he describes, following Lefevre, as “Moghan.”

This Kaffel piece has field

“guls” that are similar to the Fraunenknecht piece and the color palette also

seems approximate to me. Mr. Fraunenknecht does not give a technical description

of the piece he presents and neither does Kaffel, but Kaffel seems to accept

Lefevre’s suggestion that this is a piece from a rare Moghan group woven in the

first half of the 19th century.

I once owned, and still know the location

of, a piece nearly identical to Kaffel’s Plate 37. Its guls have slightly less

proportionate height than do those on the Kaffel piece, but its design and color

palette are otherwise identical. I have, of course, had this latter piece in my

hands and can testify that, while I am not sure I can reliably recognize the

line between Moghan and Shirvan weaving, my piece seemed to me rather

classically Shirvan. It has white cotton selvedges, brown and white wool warps

that are not depressed, a color palette that seems to me frequent with weavings

estimated to be Shirvan, border designs that seem Shirvan to me, and a handle

that is similar to that of other Shirvan weavings I have encountered. I asked

Kaffel once about the “Moghan” attribution of Plate 37 and he said frankly that

Lefevre was the only one really claiming that this piece was Moghan.

So

my questions are, what is the basis for Mr. Fauenknecht’s suggestion that the

piece he has provided with similar field guls, is Shahsevan? Does he think,

absent a technical analysis, that we can accept Lefevre’s suggestion that

Kaffel’s Plate 37 is Moghan? If so, does that mean that Plate 37 is actually

properly seen to be a Shahsevan piece? And where would he put my nearly

identically designed and colored piece that seems to me to have some markedly

Shirvan qualities?

Regards,

R. John Howe

Posted by Filiberto Boncompagni on 03-26-2003 08:10 AM:

Hi John,

Both prayer rugs in Bertrand’s Salon are from Kaffel’s

book.

The one you show first is plate 16, the other is plate

21.

Regards,

Filiberto

Posted by Bertram Frauenknecht on 03-26-2003 12:50 PM:

Hello John,

let me start with the "Afshar" Bidjars, I had written Afshar

Shahsevan. You can find this attribution also for Soumacs in Tanavoli. I learned

that in the 70's when I was told in Persia that the best Bidjars are made from

Shahsevan and are called Afshar.

I learned a lot later, that these were

displaced by Nadir Shah in the 18th c.

Thanks Filiberto, I forgot to give

Ralph credit for his wonderful book.

Actually plate 37 has a perfect

Shahsevan border system. The gul like octogons are in many Soumac and reverse

Soumac bags.

I suggest to look at map 1. You'll see the frontiers of the

Khanates being part of the confederacy.

I would call every tribal group in

the Transcaucasus and Azerbaijan Shahsevan when they were Shi'ites and not

original Caucasian people. With very high probability they had joined in the

beginning of and during the 17th century to form a strong and powerful

confederacy.

So it is not really important wether a rug was made in Moghan or

Gendje or Shirwan as long as it carries Shahsevan designs.

Structure is the

next step.

There is no question in my mind that several Shirwan rugs can be

Shahsevan as well.

Here I load some images of typical Shahsevan

designs.

Best

Bertram

Posted by R. John Howe on 03-26-2003 03:50 PM:

Hi Bertram -

Thanks for this additional comment and for the associated

images. Some of these, that you indicate are typically Shahsevan, resonate, at

least for me, with some Turkmen usages.

I refer in particular to the

first image that is informally sometimes called a "bird on a pole" border, to

the border with the double gottchalk and a center rosette, and to the "guls" in

the rugs in Kaffel's Plates 16 and 37. I find that these latter devices resonate

for me with the field guls in Jon Thompson's cover piece on his December 16,

1983 Sotheby's NYC catalog.

Are these similarities simply a reflection

of a broadly used reservoir of "Turkic" usages or is it possible that there are

also Shahsevan-Turkmen weavings or even Turkmen-Shahsevan ones?

Wendel is

going to be very disappointed if this is possible.

Regards,

R. John Howe

Posted by Bertram Frauenknecht on 03-26-2003 04:02 PM:

hi John,

it's as you say, many of the people came from Anatolia. Families,

groups of Turkmen origin who were not happy with the Ottomans. They took the

chance of more independance and left.

This has happened in the middle ages

everywhere. That's why you have the Amish and that's the Mayflower.

I see a

lot of Turkmen designs in these rugs and flatweaves. If they are

Turkmen?!

Bertram

Posted by R. John Howe on 03-26-2003 08:43 PM:

Hi Bertram -

So you see one major flow of population in this area as

coming from Turkey.

This will provide some vindication for an argument

that Wendel made in a careful paper at ICOC in Philadelphia in which he showed

that the "wine glass and halyx leaf" border in many Caucasian rugs was only half

of a more comprehensive design and that it could be found in Turkish

architecture. P.R.J. Ford, perhaps mostly to lend some spirit to the discussion,

stood up and said that it was a perfectly marvelous presentation but clearly

wrong since it was well known that Caucasian designs were sourced in

Iran.

Not to press too hard, but if you see versions of many of these

designs you offer as also used in Turkish and Turkmen rugs, how can they

function to delineate those that are distinctly

Shahsevan?

Regards,

R. John Howe

Posted by Bertram Frauenknecht on 03-27-2003 07:18 AM:

Hi John,

as I said before, the Shahsevan were not one body or one tribe.

They were rather like a mosaic put together by many different small groups.

Their chiefs declared them as Shahi sevani and so they slowly grew together.

That's why I said that those soumacs must have had a reason, for they don't

exist in any other group or tribe.

Sure there are other soumac weavings, it

is the name of a technique, but the Shahsevan soumacs can not have existed

before. We would have examples from somewhere else.

It is the variety and the

mixture of designs which form a picture specific for these

people.

Interestingly these soumacs were further on made even by displaced

groups. I remember a typical Shahsevan piece with typical Gashgai features. (A

group of S. was send down to the Gashgai region by Nadir)

This mixture of

designs must have been used also in rugs. That's why they look so similar to the

soumacs.

Best

Bertram

Posted by Richard Tomlinson on 03-28-2003 07:26 AM:

confusion reigns....

hello all...

hello bertram...

as a completely unread and

uneducated rug novice, i am finding this fascinating salon difficult to follow.

the way i am reading it is that the 'shahsavan' were thought by many to

be from a distinct geographical region. that is, a rug was either shah or moghun

or shirvan etc.

it appears to me that bertram is now saying that many

rugs considered 'caucasian shirvan' or 'caucasian moghun' or others are in fact

shahsavan. that is, the shah confederecy extended beyond the geographical

boundaries that are considered by many to be 'shahsavan'

is this right?

feel free to shoot me down :-)

but i am VERY confused because bertram

also says;

"Here are three examples of rugs that I believe can properly

be called Shahsevan."

so - is there a "pure" shahsavan rug? are the rest

then 'hybrids'?

if you are confused by what i am asking - join the club

!!

thanks

richard

Posted by Bertram Frauenknecht on 03-28-2003 04:39 PM:

Hello everybody, hello Richard,

it is a bit confusing, as in the past

everybody thought, Shahsevan is a small group of nomads living in the southern

Moghan.

Although several authors had written about S. groups in the areas

between Hashtrud and Veramin nobody took this into consideration. But 'there

must be more to this tribe'. When I stumbled over travelling books with

historical contents it became soon clear to me that Moghan was not this tiny

part we know now, but a huge area with fertile lands and steppe perfect as

grazing land. In the meantime I know that from there these people spread out and

used what they could, which means considering the power their chiefs had with

strong followers behind them, they were very influential in their time.

Even

Tanavoli estimates 800000 members in the late 18th century. This is an enormous

figure considering time and place.

With historical facts a picture forms. The

Shahsevan influence and their people were spread out according to the map you

can study

as map 1. This means to me that their rugs were woven in a much

larger area as we think so far. When we study transcaucasian rugs there are many

which carry designs that we know from soumac bags. Why would the people who

lived there for ages change their designs? They did not . We have many pure rugs

that are clearly belonging into a specific group. But when they carry designs

and symbols which we know from Shahsevan bags then we should at least accept the

possibility that they are rugs from Shahsevan groups.

I don't think that rugs

or bags from our times carry any specific connection to old times. And please

try to get a feeling for the fact that since 1828 the Russians are the masters.

Since ca. 1875

there are synthetic dyes there.

This has changed the

selfunderstanding of these people.

Remember in 1890 their kids went to

highschool!

I'm sorry to say that, but those "Daghestan" bags found in

Mekka

remind me of what I can get in the bazaar in Istanbul as the usual

tourist trash. In 1975 I could still find amongst hundreds of rugs one old

Chamseh in Dshidda. One!

Would anybody believe that the Hadjis are more

stupid than the dealers in Mekka?

You should see the soumacs that the

Shahsevans produce now.

I try to load one

tomorrow.

Best

Bertram