The Salon du Tapis d'Orient is a moderated discussion group in the manner of the 19th century salon devoted to oriental rugs and textiles and all aspects of their appreciation. Please include your full name and e-mail address in your posting.

The History of Rug Books:1877-1970

by Keith Rocklin

“A judge at common law may be an ordinary man; a good

judge of a carpet must be a genius.”

Edgar Allan Poe, Philosophy of Furniture

Genius has probably played a small role in the literature dealing with the Oriental rug. For over a century this vast body of work, consisting of thousands of titles, has been a fountain of misinformation and fanciful myths, reflecting the ignorance and prejudices inherent in one culture’s unfamiliarity with the undocumented but profound and essential art of another culture.

In 1917 H.G. Dwight, a traveler in the Middle East familiar with its languages and customs, wrote the travel account Persian Miniatures. He begins his book with the acknowledgements, in which he cites his friend A. Cecil Edwards, the British rug agent living in Hamadan and elsewhere, as an expert capable of writing a book on the subject of rugs surpassing all the others. Unfortunately Edwards didn’t publish his classic The Persian Carpet until 1940, and in the interim, as Dwight undoubtedly would concur, many a reader was led astray.

Dwight devotes one entire chapter to a scathing and prescient evaluation of rug books and scholarship up to that time. He says: “It is no flattering proof of what we know of the East and its arts, or of the standards of criticism accepted among us, that publishers can go on issuing these more or less expensive picture books, improvised out of Mr. Mumford and water.”

This reference is to John Kimberly Mumford, an Englishman who traveled throughout Turkey and Iran by camel, donkey and cart, who published his landmark book for the layman called Oriental Rugs (1900). A literate man who accurately recorded what he learned from bazaars and villages, he gave rise to the popular literature of the rug. While his own book went into many editions for the next twenty years, many new general books aimed at the public appeared. Almost all of these benefited from Mumford’s hands-on research, but most promoted and embellished dubious and romantic notions circulated by merchants promoting the product.

Referring to a book written in 1913, Dwight says: “Of all the gibberish that has been written on this subject, it would be hard to find more crowded into one page than may be read in Dr. G.G. Lewis’ Practical Book of Oriental Rugs (1911).”

While Dwight rebuked the popular books of the time, he commended scholarly efforts such as those of Wilhelm Bode, F.R. Martin and Julius Lessing (who wrote the first book on rugs in 1877). These authors and others (e.g. Robinson and Riegl) pioneered research into classical rugs and produced impressive folio editions which promoted the Oriental Rug as serious art. The most ambitious and important of these was Martin’s A History of the Oriental Rug before 1800 (1908).

One of Dwight’s chief criticisms was aimed at the mislabeling of rugs based on hearsay derived not from direct experience, but from earlier rug books or, worse yet, the inventions of rug merchants. Speaking of the authors of rug books, he says “And I, for one, am unable to comprehend their childlike faith in the gentlemen of the trade.” He goes on to say about rug dealers that “Few of them…ever in their lives hesitated for an answer. For the Oriental point of view is that courtesy requires an answer to a question, the actual truth of the reply being quite a secondary matter.” Nor have they, he says, “ever troubled themselves about little matters like geography, orthography, philology, or ethnology.”

Dwight frequently cites errors in these matters in the current books. His was a call for more rigorous approaches to rug studies. By and large this went unheeded, with few exceptions, for decades. He was ahead of his time in suggesting that attention be paid to rugs depicted in paintings and to references in early Arabic documents and others. Also, remarkably, he calls for the thorough inspection of structure for purposes of identification, an idea that didn’t take root until the last quarter of the twentieth century.

Although most authors of rug books willingly promoted and adopted uncorroborated ideas and labels learned from rug dealers, most still warned their readers to be suspicious in their dealings with rug merchants.

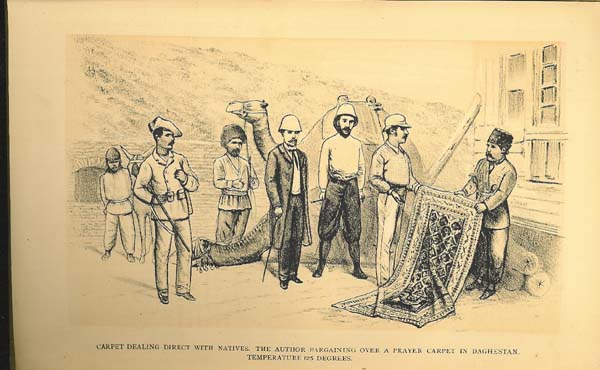

Herbert Coxon took this further than most. He was a British rug importer who wrote the earliest book on rugs originally appearing in English: Oriental Carpets, How They are Made and Conveyed to Europe (1884).

He was an intrepid traveler who established a direct importation route to England from the Middle East, determined to eliminate the middleman. As he says, only two years before his voyage, he could not have traveled as freely as he did without being enslaved by Turkmen tribes. The Russians had just decisively defeated and subjugated them. He had no trust in or sympathy for dealers he encountered. “In all my dealings with them I never came across one that I felt satisfied was thoroughly honest and fair. The whole of them were…downright rogues.” He also adds: “Great tact and ingenuity are needed to get the better of them in business. Plain, straightforward dealing seems an impossibility to them.”

Coxon goes on to recount his exasperation with their long drawn out methods of dealing, their pretense of wounded pride when a lower offer is made, and finally their acceptance of his final offer only as a “gift” that will lay the groundwork for fairer dealings in the future. The author always had his guard up – so much so that he eschewed the services of interpreters because “Those who have good linguistic capacity are generally such cheats that it is impossible to use them as mediums without exposing one’s self to the annoyance of having to counteract and prevent an unlimited fleecing.”

Despite Coxon’s shortcomings adapting to a different culture, he can offer some substance in helping us understand how rugs were then made. He observes at one point that while most of the nomads wove rugs, there were other weavers who offered their services from village to village and spread the same designs. Here is an idea that hasn’t been considered much in our own time, and is an example of the occasional insight we can gain from the early books.

Years later another but less wary English traveler, Hartley Clark, who wrote Bokhara, Turkoman and Afghan Rugs (1922), recounts an amusing swindle in which he was the victim. Sold a “200 year old rug” in the bazaar, he takes it home, immerses it in a wash basin and dumbfoundedly watches it bleed red. So begins the chase to find the fraudulent vendor, never a promising pursuit.

An account in a book by Edna Roberts, Oriental Rugs, How to Judge and Know Them (1928), illustrates an instance of what Dwight would call a “tongue in a capacious cheek”. She tells of a dealer who told her that only in his homeland, from which he imports his rugs, can sheep be found whose wool comes in such a variety of rainbow colors that no dyes are needed.

Other early books are amusing because they are fraught with bad advice, like Ellwanger, Oriental Rugs, A Monograph (1903), which urged his readers to snip off those unsightly kilim ends on Belouches. Years later in one of the most widely distributed American books of the 1970s, dealer Jacobsen, in Oriental Rugs, a Complete Guide (1962) wrote that when customers brought in their worn rugs he would advise them to chuck them in the trash can immediately. Since there were plenty of sound ones available in superior condition, why settle for less?

But good advice is often proffered in these early books, and applies as much as ever. Even in the above mentioned and maligned The Practical Book of Oriental Rugs by Lewis, this sound advice is useful today:

Dealers and Auctions

“Few Europeans or Americans penetrate to the interior markets of the East where home-made rugs find their first sale. Agents of some of the large importers have been sent over to collect rugs…and the tales of Oriental shrewdness and trickery which they bring back are many and varied. We have in this country many honest, reliable foreign dealers, but occasionally one meets with one of the class above referred to. In dealing with such people it is safe never to bid more than half and never to give over two-thirds of the price they ask you. Also never show special preference for any particular piece, otherwise you will be charged more for it. No dealer or authority may lay claim to infallibility, but few of these people have any adequate knowledge of their stock and are, as a rule, uncertain authorities…So it is that an expert may occasionally select a choice piece at a bargain while the novice usually pays more than the actual worth. … Dealers can always find an eager market for good rugs, but poor ones often go begging, and in order to dispose of them the auction is resorted to. They are put up under a bright reflected light which shows them off to the best advantage; the bidder is allowed no opportunity for a thorough examination and almost invariably there are present several fake bidders.”

THE RISE IN POPULARITY OF THE ORIENTAL RUG

(and books about them)

AMONG THE PUBLIC AND THE WEALTHY

Popular rug books from the early 20th century proliferated to such an extent that they went into many editions and are still common today. In addition there were many monographs which were given out or sold cheaply as promotions in rug and department stores. This stemmed from a demand for rugs as home furnishing in America and Europe that coincided with a new awareness of the Oriental rug. As a result, the second half of the 19th century spawned massive importation, with European firms setting up in Turkey and Persia and promoting the manufacture of new products.

But the original impetus for this phenomenon can be traced back to the early 19th century, when Western scholarship embraced the study of foreign cultures more than ever and museums sought archaeological treasures outside of continental Europe. As a consequence, the Islamic world gained a particular fascination for travelers and for a public eager to read their accounts.

At the same time, with the full effects of the industrial revolution bearing down on European and American culture, a nostalgia for and appreciation of traditional decorative arts manifested itself in various social and artistic movements. Sometimes international exhibitions included various handicrafts from around the world, including that of the Oriental rug. For the first time an understanding and appreciation of this ancient product as high artistic expression entered the Western consciousness.

In the mid 19th century the influential artist William Morris witnessed classical Persian rugs and virtually accorded them parity with painting and other fine arts. He even began to produce hand-knotted rugs in England by the time-honored methods, using designs inspired by those he saw in rugs such as the Ardebil carpet, which had just been obtained from Middle East and exhibited in London. Through various intrigues this rug, or its secret pair, arguably the most famous of all rugs in the world, was to change hands many times among prominent dealers, collectors and museums well into the next century.

Suddenly the most admired and historically important rugs were in vogue among American and European millionaires and various museums. A competition began for the oldest and most magnificent examples produced by the legendary courts of Turkey, Persia and Egypt and dating back centuries.

This was greatly assisted by dealers and carpet firms that catered to the wealthy and combed the mosques and villages of the Middle East for the most elegant and sought after pieces. In 1903, 1906 and 1913 the Tiffany Co. published three volumes of rugs that illustrated the most expensive tastes of the time. These selections would be equally valued today. In 1923 the Altman family published its collection (in the form of a catalog), which it offered at an auction sales room now known as Sothebys. In 1910 Yerkes published painted reproductions of his collection, one of the finest ever assembled. Bengiuat, one of the most legendary of early rug dealers and who had many wealthy clients, also published a number of exhibition or auction catalogs displaying important rugs. And Ballard, the important St. Louis collector, published four exhibition catalogues of his extensive collection, including one of his daughter’s.

So in less than a few generations much of what remained from the ancient courts and villages entered the West. Gradually early art historians of the rug published accounts and mounted exhibitions which marked the beginning of rug scholarship. Scholars, collectors, museums and dealers commissioned lavishly produced folio-size works from the 1870s up until the 1920s which presented rugs in color and in impressive formats which attempted to elevate their status into the realms of high art. Today these weighty (literally) books are scarce and command high prices. It was this period, then, that effectively preserved the great bulk of classical rugs of which we are aware today. Many were eventually displayed in museums or important exhibitions and documented in books in the coming years. Others remained in important private collections.

THE FIRST HALF OF THE 20TH CENTURY

Some of the publications from this period were monographs which were given out or sold cheaply as promotions throughout the country – probably in rug and department stores. In the first part of the 20th century the rash of “popular” literature about rugs published in English found their counterparts in many well-illustrated books in German. It is interesting that occasionally an early German book about rugs would be translated into another language, but not into English; and that no English book would appear in German or any other European language. These popular books in both English and German went into so many editions that today most of them are still quite plentiful, proving that they must have been very widely read.

The best of the popular German Books at this time were: Orendi’s two volume Das Gesamtwissem uber Antike und neue Teppich des Orient (1930), Neugebauer and Orendi’s Orientalische Teppichkunde (1909, but many other editions up to 1930) and Grote-Hasenbalg’s Der Orientteppich (expanded into various single and triple volume editions in 1922). All of these editions have good quality plates, many in color, that give us a good idea of which rugs were most prized. Often they are the same ones that would be considered so today. For example, Grote-Hasenbalg’s selections, expanded from illustrated postcards by R. von Oettingen (1911), include famous examples often cited today as among the best of type.

In the same period a large volume by Jacoby, Eine Sammlung Orientalischer Teppiche (1923) documented excellent rugs with an emphasis on classical ones. Important historical treatises on classical rugs appeared by Bode in 1917 and then by Bode and Kuhnel in 1922 (later to be revised and translated into English by Ellis in 1970). It should be mentioned also that the Swiss dealer Meyer-Muller published a catalog of his collection in 1917, mostly top-quality 19th century rugs that would remain somewhat intact and be offered for sale in the 1990s at Christies New York. The devastation of World War I must have tempered the German taste in favor of less costly but often aesthetically superior rugs. In the German popular books an appreciation of tribal, village and Caucasian rugs came into the fore for the first time. Many illustrations of outstanding rugs like those collected today appeared in these books. In them there is much less emphasis on the lavish decorative and fine city rugs sold in America and documented in New York city auction catalogs just prior to World War I through the end of the 1920s.

By the 1930s disposable income for and interest in Oriental rugs fell sharply. Depression and preparation for war almost entirely eliminated new publications on rugs. Except for Arthur Dilley’s Oriental Rugs and Carpets in 1931, only verbatim reprints in English of general books appeared. One of these was Mary Ripley’s curious symbolism-laden work from 1900, The Oriental Rug Book, which appeared in 1936. In 1937 there were two more: Rosa Bella Holt’s (1901) Rugs and Walter Hawley’s (1913) Oriental Rugs, both with “Antique and Modern” in the subtitles. In 1949, the French Armenian dealer Achdjian published Le Tapis, with hand-tipped and color plates and a dual text in French and English.

THE SECOND HALF OF THE 2Oth CENTURY

The German speaking countries have always been prominent in the study and appreciation of rugs. From both an art historical and what today we would call the collectors’ point of view, German authors – usually dealers or scholars, or men who were both -- have always brought a highly developed connoisseurship to the field. Many of the most important and thorough of the early studies, including the first rug book ever, appeared in German.

In 1959 the Bernheimer firm of Munich, later of Berlin and London, published their collection of important rugs in Alte Teppiche des 16.-18. Jahrhunderts. Many of the examples appearing in this book were sold at a highly publicized and greatly successful sale at Christies London in the late 1990s when the firm closed its doors permanently after more than a century of dealing in antiques and rugs.

The beginning of the rug collecting boom still in full force was most prominently initiated by the efforts of Ullrich Schurmann in the early 1960s. It was at that time that he began promoting and exhibiting Caucasian rugs, publishing the book that created most of the terminology still used for this group (Caucasian Rugs, 1st English ed. 1965). Other books accompanying his highly influential exhibitions of top-flight collectors’ pieces followed, including Central Asian Rugs (English ed. 1969). These two books were among the first to deal with only one group of primarily 19th century rugs and woven artifacts, and did it better than any previously.

Collectors now began to focus on specific groups and were on the road to sorting out the most recognizable, the rarest, the oldest and the best in each category. A demand for a literature corresponding to specific areas of interest began to be met by a new type of book on rugs: one that appealed to collectors and reflected their increased knowledge and sophistication.