Posted by Patrick Weiler on 02-02-2003 11:32 AM:

Pile sumak?

John,

The second page of the Salon shows a Shahsavan khorjin face. You

say:

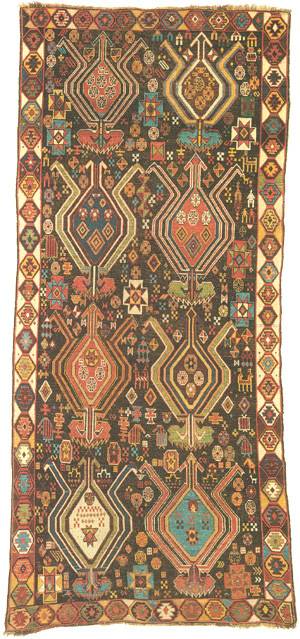

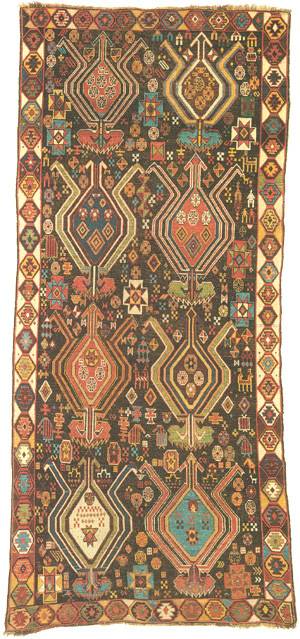

"The next piece was, I think, also in Jerry's ACOR exhibition.

This is a Shahsavan sumak khorjin bag face. Joe said that at one time he

owned both halves of this khorjin, but that he had separated them and sold one

to Wendel Swan. A very similar complete khorjin set was published as Plate 113

in the 1996 ICOC "Atlantic Collections" catalog. Wendel pointed out from the

audience that this is a quintessential Shahsavan design."

On my monitor

it appears to be a pile woven khorjin face. One feature that shouts "pile" is

the white outlines of the diamonds in the field.

Another is the white border

with colored diamonds.

The Atlantic Collections Khorjin is pile

woven.

Sumak or pile, I would like to have it in MY

collection.

Patrick Weiler

Posted by R. John Howe on 02-03-2003 05:04 PM:

Pat -

Wendel needs to speak up just to confirm, but I think you may be

right, that this is a pile piece.

As you may remember there is a kind of

debate, with some folks claiming that it is doubtful that the Shahsevan wove

pile pieces, and others thinking that there are not a few pile pieces that

should rightfully be attributed to the Shahsevan.

I think the sumac

labeling is just my error.

Regards,

R. John Howe

Posted by Wendel_Swan on 02-03-2003 05:14 PM:

Hi Pat and all,

Joe's Shahsavan khorjin face is definitely pile, not

sumak. You may not be surprised to learn that mine, its mate, is also pile. The

colors and wool quality are almost unsurpassed.

Wendel

Posted by Bertram Frauenknecht on 02-04-2003 05:15 AM:

Pile Shasavan

Hi everybody,

It is really amazing to see how long a fairy tale stays with

educated people. Why should a huge confederacy as the Shasavan not have produced

pile rugs. On my last visit to their dwellings I was sitting on pile rugs that

they claimed to be made by them. That was 1980.

And those rugs looked as poor

as the makers. ' '

'

There are so

many so-called Caucasian rugs that don't fit in any of the normal criteria and

which are attributed to South-East Caucasus. The question who lived there can

easily be answered.

I bet Wendel is smiling now.:-)

All the

best

Bertram

Posted by Mike Tschebull on 02-04-2003 08:52 AM:

I suppose, in the end, it’s harmless enough to insist that “Shahsavan” wove

“pile rugs”. Nevertheless, let me have a go at it. First, it’s better to define

the weavers in question as “Azarbayjani nomads”, so there’s no confusion over

settled vs. nomadic peoples. “Shahsavan” is so imprecise.

Then, it’s

instructive to delve into statistics a little bit, which will quickly show that

the idea of “huge” numbers of Shahsavan is, indeed, a fairy tale. Settled

villagers in Azarbayjan - and in the Caucasus - hugely outnumbered nomads in the

19th century, and were the source of most weaving, especially pile

weaving,

Next, a good conversation with a competent anthropologist and/or

some field work will reveal enough about the technology of nomadism so that the

idea that Azarbayjani nomads were ever more than fringe weavers of pile objects

is shown to be nonsense.

It is of course frustrating to be unable to

accurately attribute rural pile weaving.

Posted by Steve Price on 02-04-2003 09:10 AM:

Hi Mike,

Could you expand on some of this? Specifically,

1.

"Azerbaijani nomad" is a term I've rarely seen used as a descriptor. Is it more

precise than "Shahsevan", and if so, in what way?

2. How many Shahsevan

tribespeople were there in the 19th century? The same number might seem huge to

one person and trivial to another. If there were enough of them to crank out

lots of flatweaves, wouldn't that be enough to crank out lots of

pileweaves?

3. What is the "nomad technology" argument that makes it highly

unlikely that Shahsevan did pile weaving? Does the same apply to Turkmen,

Belouch, Yoruk, etc., nomads?

Regards,

Steve Price

Posted by Bertram Frauenknecht on 02-04-2003 09:35 AM:

Hi Mike,

I agree that much weaving was done by villagers. I didn't say

anything about nomads, for me Shasavans are not necessarily nomads. This tiny

nomadic group we still have are only a small portion of the Shasavan. A settled

nomad still after generations would consider himself part of the group, even if

he hates the nomads for a number of reasons. (Fieldwork in Turkey)

Their

Khans were telling them what they are, as it happened in every feudal society.

Just look into Germany 17th c.

Fieldwork done 150 years after their

structure broke down simply cannot reveal much (or anything at all) of their

life then. Only witnesses from those times can.

What is still the same

(compare Turkmen nomadic life), a wealthy nomad (being a successful

entrepreneur) had and has today several wives. Through that they make space for

weaving which adds to their wealth. His poor neighbour has to sell the wool he

produces, for nobody has time to do something with it.

I believe that our

ideas about Shasavan has little to do with the people who lived in Azerbaijan in

the 17th and 18th century and not too much more with the ones in the 19th, when

they went through their distruction.

The poor fellows that Tapper researched

in the 1960's were far away from their ancestors.

I remember quite well how

impressed I was by these wild nomads I visited first in 1972. What a world

opened to my eyes.

Just that I didn't really understand anything. I knew

nothing about their history. Things have changed.

best

regards

Bertram

Posted by Bertram Frauenknecht on 02-04-2003 09:59 AM:

Just a word about statistics,

In 189o Hahn, a teacher at the 'highschool'

in Tiflis writes about:

" the 'tatares' who come from the southern Moghan,

use to settle in the outskirts of the city with piles of rugs and weavings for

sale.

They speak a language which is a mixture of Persian and Turkish"

He

numbers them to 900 000 people.

Hard to believe!

Bertram

Posted by Bertram Frauenknecht on 02-04-2003 10:17 AM:

Sorry,

I missed completely the nonsense part that nomads don't weave or

weave little. Those poor nomads were often not so poor. They loved to be

independant. That's why many became nomads again after being forcefully settled

for many years.

I seriously doubt that an anthropologist understands much of

nomadic life. We had some strange examples during Nazi times and you all know

what happened. I bet you mean an ethnologist.

And again, fieldwork today,

oops...

Bertram

Posted by Rick Paine on 02-04-2003 04:38 PM:

I think we have a little European/N. American jargon problem here. In Europe,

an "anthropologist" is one who studies human physical characteristics. This

person would be labeled a "physical" or "biological" anthropologist in North

America. In North America, "anthropologist" refers to a whole range --including

physical anthropologists, archaeologists, ethnographers, and ethnologists (the

last two often grouped here as cultural anthropologists). It is pretty typical

in N. America to use "anthropologist" to describe an ethnographer.

Really

fascinating stuff in this Forum. Thanks.

--Rick

Posted by Mike Tschebull on 02-04-2003 07:05 PM:

One problem with the term “Shahsavan”, as Herr Frauenknecht makes clear, is

that to some, it implies settled as well as nomadic people. “Shahsavan” means

“nomads” to me and to most other specialists in this area; there is and has long

been a rather sharp distinction between nomads and settled people in Azarbayjan.

Another problem is that there are/were Azarbayani nomads not belonging to the

“Shahsavan”.

Headcount: An 1870 estimate is 12,000 Shahsavan families.

Tapper estimates 60, 000 - 80,000 people. The number rises and falls over time,

depending on settlement policies in Iran, border disputes, winter pasturage

available, etc.

The number mentioned by Herr F. from Herr Hahn - 900,000

- seems wildly off the mark. A well-regarded Historian, Muriel Atkin, estimated

that the entire population in the Caucasus at the beginning of the 19th century

at a quarter of a million.

Nomad technology: I don’t think it’s a secret

that the biggest problem when sleeping on the ground in cold weather is keeping

the ground chill away. The kind of rugs Bertram’s talking about won’t do the

job, won’t provide a warm mattress for high altitude nomads - and are too heavy

to haul around. Lighter, warmer and cheaper to make are felts. There is plenty

of information on Shahsavan use of felts to sleep on, often backed by jajim or

gilim. To carry this train of thought a bit further, there are pile rugs used by

transhumants and nomads, but they are not the same as most Caucasian and

Azarbayjani pile rugs. Good examples of pile rugs used by nomads are the ivory

and dark brown “sleeping fleeces” woven at one point by the Beni Ourain in the

Middle Atlas. Maybe six knots to the sq. inch, lots of thin wefts and warps,

light weight, very long pile, very warm, very much like a sheep skin.

As

an aside, Ali Hassouri told me that when he was a child growing up in Bostanbad

(a town in eastern Azarbayjan), he sat on coarse, long-piled goathair

gabbeh-like floor rugs. Villagers in the region still sit on locally woven rugs

if they can afford them. The rugs used domestically in eastern Azarbayjan have a

standard format.

“Wild nomads”: Yes, sitting on a mountaintop at about

2500 meters, looking out at Shahsavan ahlechik arrayed on slopes above the cloud

line is impressive. Actually, there is a powerful connection between today’s

mountaintop Shahsavan and their ancestors that is hard to miss - and the view

alone is well worth the trip. (See the Frauenknecht article in a 1981(?) Hali

about visiting Azarbayjani nomads.)

Earlier fieldwork: The problem is,

there really isn’t any to speak of. That’s why Richard Tapper’s large body of

work is so important. Yes, he’s an anthropologist. You have a bone to pick with

how he defines himself, take it up with him. He’s quite approachable. And yes,

he would best be described as a cultural anthropologist.

Rich nomads:

Sure there are/were rich nomads and they weave/wove (or had woven) high quality

textiles. Witness the amount of silk in nomad woven artifacts.

Posted by Steve Price on 02-04-2003 08:53 PM:

Hi Mike,

Thanks for the clarifications. One more question: your

argument against Shahsevan weaving of pile seems to focus on the properties of

rugs as places to sleep. But pile can be used in lots of things besides sleeping

rugs, easily exemplified in so much of the output of Turkmen, Belouch and many

other nomadic tribal peoples. Is there some reason why the Shahsevan could not

or did not make pile stuff? Or have I missed the point of the debate

altogether?

Regards,

Steve Price

Posted by Mike Tschebull on 02-04-2003 09:18 PM:

Not only places to sleep, but places to sit.

It seems that the

Azarbayjani nomads specialized above all other west Asian nomads in the use of

"sumak" for transport bags. Why is that? Clearly, the best Shahsavan transport

bags - best designs, best color - are sumak; many/most of the pile bags - like

Wendel's - are derivative, and may be village weaving.

It must be kept in

mind that a lot of pile-woven bags were woven for the bazaar, and ultimately,

Western consumption.

To paraphrase John Cage, it troubles me to see how

much Turkman weaving is pile.

Posted by Steve Price on 02-04-2003 09:55 PM:

Hi Mike,

You say, ...it troubles me to see how much Turkman weaving

is pile. I don't want to put words in your mouth, but is it correct to

interpret this as meaning that you are skeptical about the general notion that

most Turkmen pile bags and trappings were made for use within the tribal

community, at least until 1875 or so?

Steve Price

Posted by R. John Howe on 02-05-2003 06:29 AM:

Mike -

And to add to Steve's question, "And if so, where are all the

Turkmen flatwoven items that are presumably the things really "made for

use?"

Regards,

R. John Howe

Posted by Mike Tschebull on 02-05-2003 07:40 AM:

John, Steve - These are indeed good questions for Turkmen collectors to

ponder. Compare the corpus of Turkmen weaving with the variety of wool and

goathair woven textiles from, say, Morocco and, well, Fars in Iran, and explain

the lack of structural variety.

Posted by Bertram Frauenknecht on 02-05-2003 08:20 AM:

Hi everybody, hi Mike (or should I say Herr Tschebull?),

I doubt that

Shasavan means nomad to any specialist. Even Tapper would disagree with you. And

they are not only in Azerbaijan, but spread all over Persia since Nadir Shah

distributed them, as they had become so numerous and lazy that they did not help

against the Afghans in 1722. That was the end of the Safavids.

For example

(fieldwork!) there is a rather big group in the Hashtrud area and further east,

all villagers who called themselve still Shasavan in the seventies when I

visited several of their villages.

Their production then was still slightly

related to what we are really talking about, those wonderful Soumac weaves from

the 19th century or earlier and their beautiful rugs.

A tribe is always also

partly settled. Or how could we explain that Soraya had a German mother and her

father a University degree

from Europe (Bachtiar). The palaces of the leaders

are still existing.

I know that it is beautiful up there on the Savalan

range. In summer! When it has 110 degrees in the valleys and the ground is

breaking up. In 2500m it is still quite warm.

I visited them last in early

March in the southern Moghan, this tiny piece that is left to them which is the

reason that there are only few left. It was cold! Still I remember this little

kid playing on the ground half naked.

Your head count from 1870 means exactly

this small part of the Moghan. Don't you know that till 1828 they were occupying

the whole fertile ground of the Moghan steppe? Spreading up the Kura , moving

into Southern Shirvan? The Khans of Baku, Shusha and Gendje were with the

Shasavan confederacy off and on.

We are talking of a group of people who were

obliged to keep an army of ca 20000 under arms. Who were even in the thirtie's

of the 20th c. able to block the connection between Täbriz and Tehran for

months.

These wonderful bags they produced were not for use. They were money!

And not for export, as most were made before export played any role.

I think

the biggest problem is that we simply cannot put our finger down and say this

rug is Shasavan, as we can do with Gashgai for example. The reason? There high

culture ended in the middle of the 19th c.

All the travellers from the end of

the 19th call them robbers, bandits, dangerous.

By the way, I consider Hahns

estimate also far too high. My point was that nomads from the southern Moghan

speaking a dialect that I know (?) were selling their rugs at the market in

Tiflis in 1890 and I doubt that they came from Persia. It is a fact that nomads,

if they were contollable, were considered as important meat producers and

whatever else they came up with. That's why I call them entrepreneurs. The

Russians needed food too.

And last, have you ever carried one of those felts

covering the tents? I rather carry five nice carpets. As more beautiful they are

as lighter they get.

Best

Bertram

Posted by Mike Tschebull on 02-05-2003 09:36 AM:

>Herr F. is making a near perfect argument for the use of the term

"Azarbayjani nomads".

>With regard to the numbers of "Shahsavan", to

paraphrase Sgt. Joe Friday, just stick to the facts.

>Roof felts

are of course heavy, but that's why on a typical ahlechik, the felts are made of

27 triangular pieces, sewn together to make three overlapping shaped covers. The

roof cover is the difference between life and death for these nomads. Lots have

died from exposure. The felt roof covers are a good example of this "technology

of nomadism". Heavy? Sure, but great insulators, which is my point regarding

their use as ground covers.

Posted by Bertram Frauenknecht on 02-05-2003 10:20 AM:

Hi Mike,

Azerbaijani nomads have been by large in the 18th and a good part

of the 19th century groups that were part of the Shasavan conferacy. Please read

Tapper more carefully.

Your point was that they did not make pile rugs for

the weight.

And now you agree that their felts are very heavy.

Do you know

why many people and especially their flock died?

The southern moghan, where

they had to go to is only for a small part plain and fertile (there is a huge

irrigation program now for

agriculture). In the adjecent hills there the

temperature is about 2-3 degrees celsius less(ca 4-6°F) than in the plain. That

proved to be enough.

Again, a visit in the 90's does not say ANYTHING about

these people 150 years ago.

Claiming they never made pile rugs is simply

absurd. You have no argument against it. They were mostly Turkmen by origine.

Not to forget Kurds. And their tradition was rugs, rugs and again

rugs.

Another question for you. Why is it that from approx. the middle of

the 19th c. there were plenty of weavers to produce a large number of Herizes,

Baghsheichs, Serapis?

A highly educated Professor in Tiflis might not have been able

to count right, why should a Sgt. Friday (maybe it was already Saturday and he

wanted to enjoy his weekend )

)

With nomadic greetings

Bertram

Posted by Filiberto Boncompagni on 02-05-2003 10:57 AM:

I think Bertram is right.

"It is a fact that nomads, if they were

controllable, were considered as important meat producers and whatever else they

came up with. That's why I call them entrepreneurs."

That was what they

were. They produced meat, wool and textiles. Part of their production was for

their own consumption, the rest was for trade!

I think we should abandon the

romantic idea that "tribal" textiles were made exclusively for the tribe’s own

use.

That doesn’t mean they were produced for the western market - I bet

there has been ALWAYS a market for this stuff and the trade is as old as the

nomadic weaving tradition.

Regards,

Filiberto

Posted by M. Wendorf on 02-05-2003 11:50 AM:

Their tradition

Dear Folks:

I think their "tradition" first and second was simple

structures and flatweaves, but I also think they wove knotted pile rugs.

I think the "they" is anyone who calls or thinks of themself as

Shahsavan. I have heard/known people who called themselves Shahsavan. I have

never known or heard of anyone who called themself an Azerbayjani nomad and I

think the distinction Mike makes is either too sharp or too fine.

One

anecdote. Some years ago I happened into a small, dingy rug shop in Middleburg,

Virginia. Striking up a conversation with the seemingly Persian owner he learned

that I was interested in old weavings from northwestern Iran. At this point he

volunteered that he was not really Persian, but "a Shahsavan man." Is he

Shahsavan, Persian, Iranian, American? Well, he thinks of himself as Shahsavan.

He then proceeded to show me several old 20th century pile village rugs that he

said were Shahsavan. To him these were clearly unmistakeable. When I told him

that there is a debate about whether the Shahsavan knotted pile rugs or not, he

simply shook his head in disbelief.

Best, michael wendorf

Posted by Mike Tschebull on 02-05-2003 02:25 PM:

Filiberto - There's no disputing what you write there, but what you write

hasn't been in dispute, so there's nothing to be "right" about.

If you

accept Herr F's definition of "Shahsavan", you render it practically useless, as

it will describe villagers and nomads in many areas of western Iran w/o

discrimination. That's why "Azarbayjani nomads" makes sense. Of course, nomads

in western Iran wouldn't call themselves "Azarbayjani nomads". It's an

anthropoligical term - hey, cultural anthropological term.

Read Tapper

for definitions.

I wouldn't put too much stock in those Virginian

Shahsavans.

Posted by M. Wendorf on 02-05-2003 02:49 PM:

if a then b?

Mike:

(1) Shahsavan necessarily refers to or means an Azerbayjani

nomad even though not all Azerbayjani nomads are Shahsavan.

(2) People

who think of themselves as Shahsavan are not now and never have been Shahsavan

if they no longer are Azerbayjani nomads and regardless of any family history

during which their ancestors were or may have been Azerbayjani nomads.

(3) People who may have been Azerbayjani nomads and Shahsavan at one

time but are now settled are no longer Shahsavan because they became settled.

(4) People who consider themselves to be Shahsavan and weave knotted

pile carpets are not Shahsavan because they weave knotted pile carpets and/or

are settled.

Are any of these four statements incorrect as applied to

your argument regarding the weaving of knotted pile carpets by the Shahsavan is

concerned?

Best, michael wendorf

Posted by R. John Howe on 02-05-2003 03:41 PM:

Mike -

Actually, it was Michael Wendorf who spoke last.

On the

other hand, Murray Eiland, who often sounds like he's from Missouri with regard

to evidence in the rug world, WOULD accept an indication by a person claiming to

be Shahsavan that he/she was that and that the pieces he/she indicated were

Shahsavan were that.

I think Murray's acceptance is based on the

liklihood that most folks in this part of the world would not claim to be a

member of a given tribal group lightly.

There may be some similar

designations that might be avoided by some ("Sart" seems often to carry a

prejorative meaning that might make some avoid it.)

What's your own

experience in this regard? Do some folks you have talked to in the field give

seemingly incorrect indications about the tribal groups to which they

belong?

Regards,

R. John Howe

Posted by Mike Tschebull on 02-05-2003 04:44 PM:

In Qaradagh, where I've had some experience, nomads I've met don't call

themselves "Shahsavan", but rather by the name of the individual tribe they're

part of. For example, I've spent time with Moghanlu families, and that's how

they identify themselves. And by God, that's where the Tapper maps show they

lived a hundred years ago. Census data shows that the Moghanlu lived in present

day Armenia two hundred years ago.

Asking questions in the field is

tricky. Ask things the wrong way, you get the wrong answer. Every professional

in the field runs up against this. Ask the weaver if she is "Shahsavan", and

she'll say yes, if only to a) please you, or b) to get rid of you. I addressed

the asking of questions in the field at the last ICOC and my paper should appear

in the next OCTS. I understand it should appear shortly. (What did the cat say

as he placed his tail across the tracks before the 5:15 came through? It won't

be long now.)

We ruggies play fast and loose with facts/reliable field

information vs. conjecture; we should be more careful.

Posted by Wendel_Swan on 02-05-2003 05:13 PM:

To begin, I had exactly the same experience in Middleburg as did Michael. The

pieces that I saw were comparatively late (20th Century) but shared some designs

and motifs that we would recognize from what we collectively call Shahsavan

flatweaves. I would not have identified any as Shahsavan myself had I been doing

the attributions. But this man was very positive and showed me articles about

his family and their connections to Persia and the Shahsavan.

Depending

upon the era, the Shahsavan have been either more or less politically,

militarily or strategically important and, during briefer spans, either more or

less wealthy.

One cannot overlook the relationship between the nomads and

the villages. Nomadic pastoralists do not live in isolation. As important

entrepreneurs, as Bertram correctly points out, they had to sell their herds (or

flocks) to and in the villages. Likewise, they needed supplies that they could

only purchase or barter for in the villages.

During difficult economic

times, a nomadic individual or family might become settled, for pastoralism was

as much an occupation as a lifestyle.

As both Bertram and Filiberto have

alluded to, trying to determine whether an individual piece was produced by a

weaver who was at that moment sedentary or nomadic is virtually impossible.

While room size carpets would have been produced in villages or towns, so could

have horse trappings, khorjin and mafrash.

Jijims and felts are objects

likely made by nomads while nomadic for their own use, but a weaver would not

spend all her time on those projects. However, I understand that some felts are

(or were) even produced in villages. If the idea is to weave things which could

be bartered or sold, then a khorjin produced by a nomadic Shahsavan is unlikely

to be much different from one produced by a sedentary

Shahsavan.

Wendel

Posted by Mike Tschebull on 02-05-2003 06:35 PM:

>Felts were usually made for the nomads by villagers who visited summer

camps.

>I think jajim and gilim were made by villagers in Azarbayjan

in much greater numbers than by nomads, if only because of the larger number of

village weavers. There is plenty of evidence of (old) village flatweaves, both

warp and weft-faced, in houses. I've seen, especially in Qarajeh, killer jajim,

tucked away because they were made by great grandmama.

>There are many

Azarbayjani pile kennereh, pushti, and kelleh which can be clearly identified as

coming from specific villages (or groups of villages) which have been in

existance for two hundred years. Diligent (and time consuming) field research

could probably identify more villages as sources of pile rugs.

>It

seems unlikely that villagers would weave mafrash, as they pile their bedding in

the corner of a room and cover it with a jajim. A mafrash is used to pack away

nomad bedding during the day, and serves as a backrest on the inside wall of a

kume or ahlachik. I've never seen mafrash in a village house, but there may have

been some at one point earlier in the 20th century, left over from the nomad

life. Other items, like camel trappings and packbands, would only have been

woven by nomads.

>I've never seen any sumak bags in village houses in

eastern Azarbayjan, and have assumed they were woven only by nomads. The large

number of sumak mafrash seems to butress the idea that sumak is a nomad

weave.

Posted by Filiberto Boncompagni on 02-06-2003 04:51 AM:

Mike,

I wasn’t disputing anything you said, and I didn’t want to

intervene in the Shahsavan diatribe.

I only wanted to stress that MOST

LIKELY tribal weaving has ALWAYS had two destinations: one for family

consumption, the other for the "bazaar". The weaving for export to the West is

just a more recent development of the latter.

I used the word "tribal"

instead of "nomad" because even if the nomads are settled, they still consider

themselves as belonging to the tribe. The Middle East - I can see it especially

here in Jordan - is still largely a tribal society.

Let’s remember, too,

that the boundary between settled and nomad was never clear-cut. There is an

history of forced settlement of tribes by the rulers followed by rebellions and

return to "nomadism". Not to mention that some tribes conduct also a

semi-nomadic (seasonal transhumance) way of

life.

Regards,

Filiberto

Posted by Bertram Frauenknecht on 02-06-2003 04:56 AM:

Hi,

the discussion is about pile and flatweave or only flatweave amongst

the Shasavan.

We know a lot about nomads and settled nomads, but also very

little for sure, as serious research (more or less) is only done in the last 20

- 30 years. Apart for very few people who know everything, most of us go with

the fact that their is little written about nomadic production in former

times.

We know, no nomadic tribe in the countries of concern produced only

flat or pile (except for the Shasavan as Mike claims).

All these tribes

continue a healthy life with nearly unbroken traditions, except now they drive a

truck or a motorcycle and produce mostly for a market. Many of them are more or

less settled or partly settled, as the herds have to be moved around for

food.

They all have their trade marks, visible and easily recognizable by

most of us.

The Shasavan basically stopped existing in about 1850 to 1860. By

far most of the research by ethnographers is done a lot later and does not

convey anything about nomadic production. Tapper in his book 'Pasture and

Politics' never mentions a word about textiles of any sort.

But we can see

rugs that show clearly designs we know very well from Soumac bags and nobody

doubts them to be Shasavan.

Often these rugs have a different weave than any

of the known and accepted (again more or less) categories.

Would it be

possible that everyone who owns a 'Shasavan' rug

comes up with structure

analysis and we compare the results and maybe define what a 'Shasavan' rug

is?

I invite everybody to send images of front and back together with an

anlysis to me. I'll categorize the material and come back with the result.

I

put up here two pile bags which I am convinced to be Shasavan.

I hope my

computer knowhow allows me to do that.

Hope it works.

Bertram

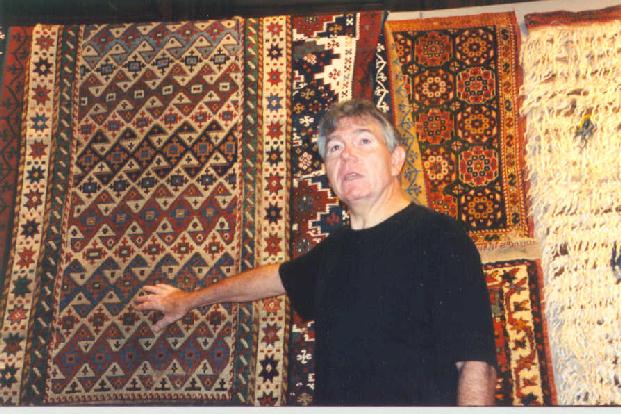

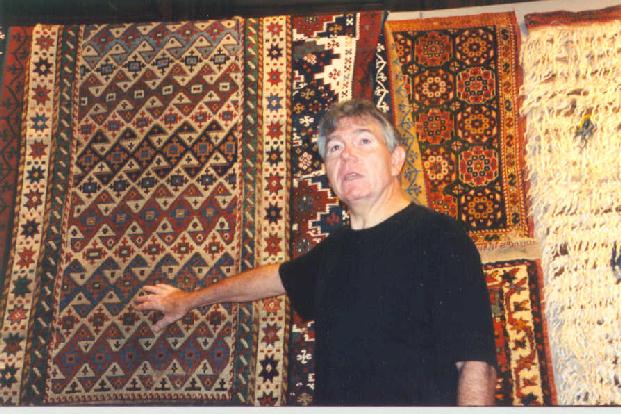

Posted by R. John Howe on 02-06-2003 06:52 AM:

Herr Frauenknecht (we Americans do not really understand the difference

between "vous" and "tu" but I will try)

We have examined some pile pieces

here on Turkotek, thought by some to be Shahsavan.

In Salon 68 in our

archives, Daniel Daniel Deschuyteneer led a discussion of the glorious "Italian

Rug."

http://www.turkotek.com/salon_00068/salon.html

Here is

the lead image of it.

Daniel's initial essay included a technical analysis of this

rug.

And earlier, in a salon on a rug morning at the TM by Wendel, he

presented another "Shahsavan" pile piece which he indicated had "distinctive

structural features."

Here is the link to that salon

http://www.turkotek.com/salon_00050/salon.html

And here

is a detail of the rug.

In a still earlier salon, Wendel offered a "yellow ground

rug."

http://www.turkotek.com/salon_00050/W10.jpg

Here is his

lead image of it.

Again, he provided a technical analysis.

And finally, in

an early salon that I hosted, this piece occurred.

I think this too is a "Shahsavan"

pile piece that Wendel owns.

There are undoubtedly others that we've

treated from time to time, but I wanted you to see that there is a fairly

accessible cache of pile weavings thought by some to be Shahsavan on which you

could collect the data you propose.

Regards,

R. John Howe

Posted by Steve Price on 02-06-2003 07:31 AM:

Hi People,

It seems to me that much of the debate is hindered by the

fact that the term, "Shahsavan", means different things in different contexts.

The Virginia dealer who refers to himself as Shahsavan is correct, just as I

would be if I referred to myself as Russian (my father was born there). But what

if we began talking about Russian traditions, using my immediate family and

experiences as the basis? I think we'd get bogged down pretty fast.

The

NW Iran/Azerbaijan distinction is similar. We are accustomed to thinking of

those as two different places because they are two different places today. But

until fairly late in the 19th century, Azerbaijan included NW Iran, and Tabriz

was the capitol of Azerbaijan. Would anyone around here call a Tabriz carpet

woven in 1850, a Caucasian carpet? It is as much a Caucasian carpet as the guy

who owns the shop in Virginia is a Shahsavan, or as much as I am a

Russian.

If the debate about whether Shahsavan wove pile stuff in the

period that's interesting to most rug collectors - the 19th century - is to get

anywhere, I think the combatants have to agree on who they mean when they say

"Shahsavan" in that period, and how they identify a Shahsavan product. Defining

it as something that must be flatwoven is pretty unsatisfactory, since it

assumes the result of the debate rather than pavng a pathway toward it. Any

argument can be resolved by simply defining the outcome in the premises. It

works every time, but doesn't advance our understanding.

Finally, I point

out in passing that Tanavoli's beautiful book, Shahsavan, appears to

include practically every pastoral group between Armenia and Bijar as

Shahsavan.

Regards,

Steve Price

Posted by Bertram Frauenknecht on 02-06-2003 08:07 AM:

Hi Steve,

thank you. I always thought somebody must come up with

Tanavoli's wonderful book.

To add to your Russian origin I have something

too.

I am Frankonian(grew up here)- that's the tribe of

Charlemagne.

Living in Bavaria, that's the State of a tribe which became

stronger through the path of history. Living in Germany (exists only since

1871), which was occupied by Roman legionnaires,

Huns, French, and who knows.

Am I now a frankonian German or

a roman Bavarian with Frankonian

origin?

Oh, I forgot, I have French Hugenot and Jewish ancestors. That makes

me a ( forget the Frankonian, my grandfathers moved here), Roman-French Bavarian

Jew with a German passport

I should be wearing Lederhosen with a black hat.

So much for tribal

origine.

Have a good day

Bertram

Posted by Lloyd_Kannenberg on 02-06-2003 08:28 AM:

Hello everyone -

Perhaps someone can help me out. Plate 14 in the

current NERS on-line prayer rug exhibit - my rug - shows a Shahsavan beetle (the

accompanying pop-up is the same as Plate 71 of Wertime's "Sumak Bags") and is a

pile rug. But is it a

SHAHSAVAN pile rug?

Lloyd

Kannenberg

Note: I've added the image of the rug for convenience, and

will remove it promptly if Lloyd Kannenberg or any representative of the New

England Rug Society objects to it being displayed here. Steve

Price

Posted by Mike Tschebull on 02-06-2003 05:45 PM:

German tribes

My wife is also from Franken, but her forbears came from the Sudetengau,

which is now part of the Czech Republic, and was formerly part of the Hapsburg

(Austrian) Empire. It's hard to pin a label on her, too.

Compared to the

US, the German-speaking part of Europe is really quite tribal, with many

citizens able to cite the Germanic tribe from which they decend.

Posted by Filiberto Boncompagni on 02-07-2003 02:25 AM:

I’m glad to see you barbarians still remember your origin!

But the tribal way of life is not

a mere reminiscence: It’s a social organization alive and kicking.

The

Bedouin tribal structure here is composed by clans (or quawm) headed by

elders. A number of these clans make up a tribe, o or qabila headed by

the sheikh. The tribes have enough power to oppose to the central

government, as it happened recently in the village of Ma’an when the Police

tried to capture the alleged killers of that American diplomat…

This

structure still exists among the Bedouins of the Arabic Peninsula.

I do not

know what kind of "tribality" is left in Caucasus/Persia, but surely it’s not

only about labels. It’s about family and blood ties.

Now, changing of

subject, I hope somebody could answer to Mr.

Kannenberg…

Regards,

Filiberto

Posted by Bertram Frauenknecht on 02-07-2003 06:33 AM:

Hello you all,

there is no need to differentiate between you and you ( or

vous and tu or Du and Sie), let's just have it the american way.

The rug of

Mr. Kannenberg or may I say Lloyd looks like a late version of a Shasavan rug.

Border and field design can be found on bags. The border drawing is known from

Anatolia and from reverse soumacs. The colors are chemical, at least what I can

see on my monitor. This means the piece is made some time after 1890. The outer

border I've seen on a number of late Caucasians.

As I'm stuck at home (too

much snow) I don't have acces to my books, but I'm sure somebody will be able to

show this border.

Look in Fokker, Gregorian or Kerimov. The weave looks like

a possible Shasavan weave, maybe made by people who stayed in Russia after the

closure of the border.

My guess southern Shirvan.

There must be several

different structures, as there are a number of different tribes (or families)

who formed the confederacy.

Bertram

Posted by Tracy Davis on 02-07-2003 09:47 AM:

Filiberto, is the reason you can refer collectively to "you barbarians"

because your people were ruling the world from Rome when the rest of us were

running around in loincloths and string skirts? You're such a snob.

I've been following this discussion

with interest, as it illustrates the problems we have with scholarship. For

example, the beetle device we all "know" is Shahsavan..... do we really know

that? Is there a piece with 100% known provenance (collected in the field from

the weaver or her immediate family, verifiably dated), that has this device? And

given the fact of design migration, and the use of talismanic symbols, why are

we so sure that this beetle device means the piece was woven by a

Shahsavan?

I wonder if this isn't an example of how theories are

advanced, develop a critical mass of acceptance, and become ruggie canon and

cited as evidence from that point forward.

I'm not really trying to make

the case that the above is happening in this discussion; I'm just wondering how

much we really *know* that conforms to currently accepted standards of

scholarship in the soft sciences.

Posted by Steve Price on 02-07-2003 10:09 AM:

Hi Tracy,

I believe you point to the most serious obstacle in trying

to assess what we know of rugs in a scholarly way - epistemology (how do we know

what we think we know?). I believe that the entire process of attribution is,

ultimately, founded on similarity in designs, motifs and layouts, and hosted a

Salon on my take on structure-based attribution awhile ago, at http://www.turkotek.com/salon_00071/salon.html

Regards,

Steve

Price

Posted by Mike Tschebull on 02-07-2003 10:14 AM:

Lloyd's rug

Tracy's right that we have no real basis for assigning that "bug" sumak

design to any specific group of weavers. It has even been speculated by

reasonably responsible Iranian dealers with field experience that the very fine

"bug" and "cloud collar" sumak bags were woven under some type of workshop

("factory") regime. So, trying to assign a rug such as Lloyd's to specific

settled nomads, whatever they call themselves, has a very strong chance of being

wrong. Trying to sort out Caucasian rugs as to origin is very difficult due to

the lack of information available.

Isn't it better not to guess,

especially when the chance of being wrong is huge? Guessing wrong, creating

"facts", means the right answer is still out there, and you are not aware of

it.

Creating a structural definition for "Shahsavan" pile rugs would put

more bogus "facts" out there.

Posted by Filiberto Boncompagni on 02-07-2003 11:40 AM:

Exactly, Tracy.

Posted by Bertram Frauenknecht on 02-07-2003 12:44 PM:

In 1981 I published a Shasavan mafrash panel in Hali (Vol IV, No 2

page

26) with the design in question. It was bought from a reasonably responsible

Iranian dealer who at the time was one of the main sources for high end Shasavan

pieces amongst other stuff. (John Wertime knows him well too) At the time nobody

had any doubt about pile material from those people.

Bogus facts seem to be

all over the carpet world. Or does any one have any proof that Kazaks were made

in the places they are named for?

I think what we need is some sort of

working definition like Ushak

or Zeychur or 'Shasavan' for pieces that fit

into certain categories and where we can say with high probability that they are

what we call them. Very often it will be hear-say as it is simply impossible to

find a 100% proof. But at least at the end we all have an idea what somebody

means when he uses a certain attribution.

I place Lloyd's rug through looking

at the structure, not only the design. And the structure is similar to pieces

that I'd call Shasavan. Aother "expert" calls the piece Anatolian.

My limited

knowledge only allows me to guess. That is for me still better than insisting on

an assertion that is lacking every probability.

As I said earlier, I've been

in Shasavan country several times and spoke with these people when they had not

yet been a tourist attraction. And I've studied the map while I studied their

history.

Bertram

Posted by Tracy Davis on 02-07-2003 01:16 PM:

Okay, Steve, I went back and read your old Salon re: the foundation of

structural attribution. I see your point.... but I'm not convinced that

structural attributions developed out of palette- or design-based attributions.

When Bogolubov et al were running around plundering the Turkmen and amassing

respectable collections, they were about as close to the source as possible, and

their labels and attributions should be taken seriously. It's not a big stretch

from there to noticing that the Tekke pieces share structural commonalities,

etc.

Maybe it's a little more dicey relying on bazaar info from southern

Iran for initial labels and attributions ... but maybe not. Rug dealers couldn't

*all* have been ignoramuses (ignoramusi?) who gave labels based solely on design

or colors. Sometimes they actually knew something. The problem is, among other

things, sorting out the wheat from the chaff.

Because apparently the

human species (or maybe it's just westerners?) has a need to label things

*before* they can define them, or refine the definition, I propose that we come

up with a good label that we can give to weavings with nomadic characteristics

that don't fit well into a category based on structural characteristics.....

like, gee, maybe "Kurdish"?

Posted by Steve Price on 02-07-2003 01:40 PM:

Hi Tracy,

You're quite right about taking attributions seriously when

they were made by people who were at the source a century ago - but the

Bogolyubov and Rickmers collections are the rare exceptions. If they were the

norm, life would be simpler.

As for attributions originating in the

bazaars (which is where most probably did originate), I don't think it implies

that the dealers were idiots. The reality is that collectors generally want an

attribution of time and place, and usually of function as well if the item isn't

a carpet, and tend to patronize dealers who provide them with attribution. That

is, the dealer who gives his customer a confident-sounding attribution may do

so, not out of ignorance, but to promote his wares.  The attributions that wind up being

published do take on an authority (just browse our archives and see how often

attributions are made on the basis of similarity in appearance to some picture

in a book or magazine, with the assumption that the published attribution is

correct). And many (most?) of the books about rugs were written by dealers.

Some, of course, were/are very well informed. We have at least two such people

debating the matter at hand right here (for anyone who doesn't know it, Bertram

and Mike are both dealers, each has written books and articles, and each has

done field work among tribal peoples in western Asia).

The attributions that wind up being

published do take on an authority (just browse our archives and see how often

attributions are made on the basis of similarity in appearance to some picture

in a book or magazine, with the assumption that the published attribution is

correct). And many (most?) of the books about rugs were written by dealers.

Some, of course, were/are very well informed. We have at least two such people

debating the matter at hand right here (for anyone who doesn't know it, Bertram

and Mike are both dealers, each has written books and articles, and each has

done field work among tribal peoples in western Asia).

I'm not offended

that you don't buy into my thinking about the epistemology of rug attribution. I

know that I represent a fairly small school of thought on that subject, and it's

OK. I think multiple views are valuable - they keep us from getting too firmly

convinced of the correctness of our misconceptions.

Regards,

Steve Price

Posted by M. Wendorf on 02-07-2003 01:56 PM:

attribution and labels

Dear Folks:

The Kurdish label is already taken so "weavings with

nomadic characteristics that don't fit well into a category based on structural

characteristics" will have to be called something else.

I also think that

color or palette plays an important role in attribution. There may be a role for

design too, I would just put it last. That is after structure, wool and after

color - including palette, value, saturation etc.

Now, please carry on.

Best, michael

Posted by Bertram Frauenknecht on 02-07-2003 02:35 PM:

How about 'BOSCO'

Based On Structural Characteristics.

The last O just

added to make it sound nicer

Great idea, Michael

Bertram

Posted by Tracy Davis on 02-07-2003 03:17 PM:

Based On Structural Characteristics Or...

Wasn't there an old joke going around about "Bilmem" rugs? Turns out that's

what the dealer said when asked what certain rugs were called ...

"bilmem" ("I don't know")

Michael, I was trying to be humorous

with the "Kurdish" suggestion, but there's a grain of truth in there. It seems

to be the preferred label given by dealers when they're really not sure what

something is.

Posted by M. Wendorf on 02-07-2003 04:02 PM:

Bilmem

Dear Tracy:

I like the Bilmem label.

There may be a grain of

truth to the use of the Kurdish label by some dealers. But that grain is limited

to the fact that some dealers use it rather than Bilmem. There is no grain of

truth to the implication that Kurdish rugs have neither any structural nor other

characteristics that give them identity. This is a myth that should not be

perpetuated.

Mike T. got it half right, we should not play fast and

loose with the facts or create bogus facts. Bertram got the other half, we

should work as hard as we can to create a plausible framework with which to

study and understand rugs tempered by the humility of knowing we can never know

it all. Bilmem.

Bertram: Bosc would be a pear. Maybe Bosco will

stick.

Regards, michael

Posted by Mike Tschebull on 02-07-2003 06:04 PM:

Access

Most dealers have bought rugs and flatweaves in the bazaars in big cities, be

it Tehran, Istanbul, or Bukhara, to pick a few. It takes less time, is less

dangerous, costs less. The attribution is less dependable, as the piece in

question has gone through more hands.

Spending extended time in remote

areas of countries where "rugs" are woven is expensive, time consuming,

sometimes a bit dangerous, hard to access, not guaranteed to be financially

lucrative, and often stressful. That's why few even make the attempt to do it.

I've never seen tourists in Qaradagh, and the locals gawk at Tehranis, let alone

Feranghi. I once saw a movie crew at about 3000 meters, though, with the

director's assistant dressed in tribal costume while holding a clipboard and a

cellphone.

Posted by Bertram Frauenknecht on 02-08-2003 10:11 AM:

Mike

it might be sad, but I know of two organizers here in Germany.

One

leaflet I remember, it said approx.:

visit to the Shasavan nomads, sit in

their tents, a day with real nomads.

And these trips cost a lot of money

too.

May I also bring back to your mind the article of Tanavoli in Hali

about Shasavan pile pieces. I can give more info about it tomorrow.

Goodbye

nomadic world

Have a nice weekend

Bertram

Posted by Mike Tschebull on 02-08-2003 04:43 PM:

mtn tops

If movie crews can get up on mtn tops, why not those legendery German

tourists? However, no tourists are gonna go very far into nomad land.

I

note with interest that the ad uses "Shahsavan" and "nomads" in the same

breath.

Caucasian rugs used to be called to be called "Cabistans",

Turkmen rugs, "Bokharas". Could "Shahsavan rugs" be next?

Posted by Richard Tomlinson on 02-09-2003 02:58 AM:

hi

interesting thread. seeing as we are talking about structure and

dyes, i have 2 relatively simple questions for the experts;

1. my

understanding is that cotton warps and wefts usually indicate a later dating

(usually 20C) BUT i have read here and there that shahsavan weavings (and i am

referring to smaller pieces here - not rugs) from the 19C ?often? have cotton

warps and wefts. TRUE or FALSE?

2. did the shahsavan (during the 19C)

EVER use cochineal?

thanks

richard tomlinson

Posted by Bertram Frauenknecht on 02-09-2003 05:03 PM:

Hi,

it is a few years ago that a dealer from Baku offered me two flatwoven

bag faces ( mixture of simple flatweave- kilim type- and brocade) with cotton

warps. I don't remember the wefts. He claimed that these pieces are called

Shasavan, although he could not combine much with it. He said that they came

from people in the southern Shirvan. They looked 19th c., no artificial

dyes.

And I am sure they used cochenille, not the Spanish brand, but from a

louse that was available in the area.

The article of Professor Tanavoli is in

Hali 45, page30.

Since these ads are done for tourists, they certainly stay

at the lowest level, Mike.

Cabistans were a sign for bilmem. That a group of

inventive dealers came up with nice names is not the fault of the Shasavan

group. They were not around to say, 'hi, these are our rugs'

Bertram

Posted by Mike Tschebull on 02-09-2003 05:32 PM:

cotton/cochineal

>Some what seem to be old mafrash from the area below Sarab have cotton

warps. Cotton pattern weft is not uncommon in old sumak bags, nor is cotton

ground weft. Some of those may be Baghdadi Shahsavan work, but some with cotton

ground weft are from Moghan. I have a Sarab rug with cotton wefts and a clear

woven-in date the equivalent of 1840, so one can safely assume cotton was

available to nearby nomads by that date. Nomads are said in the past to have

come down to Sarab to trade.

>Fred Mushkat had a very finely woven

"Shahsavan" packband with cochineal as the only red dye in his bands exhibition

at ACOR 6

'

'

The attributions that wind up being

published do take on an authority (just browse our archives and see how often

attributions are made on the basis of similarity in appearance to some picture

in a book or magazine, with the assumption that the published attribution is

correct). And many (most?) of the books about rugs were written by dealers.

Some, of course, were/are very well informed. We have at least two such people

debating the matter at hand right here (for anyone who doesn't know it, Bertram

and Mike are both dealers, each has written books and articles, and each has

done field work among tribal peoples in western Asia).

The attributions that wind up being

published do take on an authority (just browse our archives and see how often

attributions are made on the basis of similarity in appearance to some picture

in a book or magazine, with the assumption that the published attribution is

correct). And many (most?) of the books about rugs were written by dealers.

Some, of course, were/are very well informed. We have at least two such people

debating the matter at hand right here (for anyone who doesn't know it, Bertram

and Mike are both dealers, each has written books and articles, and each has

done field work among tribal peoples in western Asia).