Posted by R. John Howe on 12-24-2002 07:48 AM:

"Upside Down" In Relation to Design

Steve -

Many will know this, but it may be useful to mention, here at

the beginning, that many "prayer" rugs are woven upside down in relation to

their design.

I have heard a couple of reasons given for this practice.

The first is that it may make it more certain that the weaver will be

able to draw the area with the arch as desired (that is, the potential problem

of a shortage of warp length at the end finished last, is avoided).

The

second is that it makes the pile flow away from the person praying and therefore

is softer against his hands (and perhaps even his head) during prayer. This

second reason is the same often given for the fact that many saddle covers are

woven so that the pile points down and so is ostensibly smoother against the

inside of the rider's thighs.

Both of these reasons may be apocryphal but

the practice of weaving many rugs with arches in what seems like an upside down

mode is evident.

Regards,

R. John Howe

Posted by Steve Price on 12-24-2002 09:48 AM:

Hi John,

I think one more explanation for the "upside down" weaving

ought to be added to the list: some of the things we call arches aren't arches

at all, and those rugs are woven right side up. Many "arches", when inverted,

look like perfectly respectable vessels or

flowerpots.

Regards,

Steve Price

Posted by Patrick Weiler on 01-01-2003 03:55 PM:

How do you know?

John,

If a rug with a symmetrical field was woven upside down, how

would you know? Technically, a symmetrical-field rug could be said to be half

woven upside down and the other half right side up.  There also may be rugs out there with a

one-way field that were easier to weave upside down, but no one bothered to make

note of it.

There also may be rugs out there with a

one-way field that were easier to weave upside down, but no one bothered to make

note of it.

When weaving the bottom half of a medallion-and-corners rug, the

weaver is actually weaving the "top" of a single niche prayer rug! If it is

quicker to do that on a symmetric rug, then why not weave a single niche rug

with the niche at the start?

What if some prayer rugs were

medallion-and-corner rugs but the weaver ran out of warp and just finished the

field flat across the top!!!

So, this upside down prayer rug theory may be less important, or at

least may have considerably less meaning than it seems.

Debunkingly

yours,

Patrick Weiler

Posted by Steve Price on 01-02-2003 09:12 AM:

Hi People,

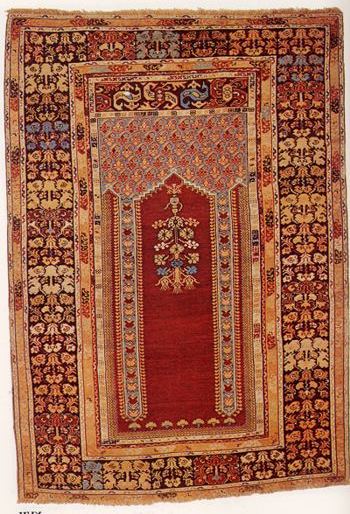

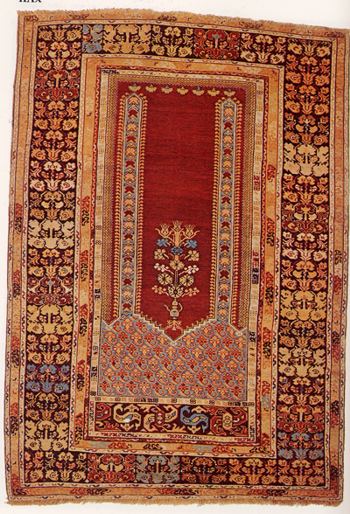

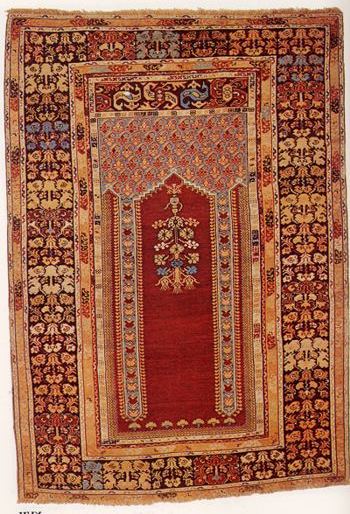

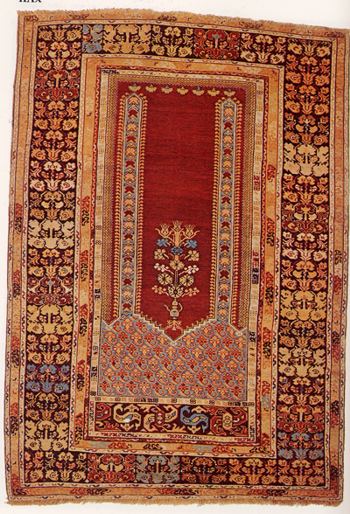

Here is a rug woven upside down if the arch is a mihrab,

rightside up if it is a container for certain motifs. It's a 19th century Kula,

shown as plate XVII in Prayer Rugs, by Ettinghausen, Dimand, Mackie and

Ellis, and is from the Ballard collection.

Notice that the flowers

and ewer in the arch are upside down if the rug is oriented in the "prayer rug"

direction (which is the orientation in the published photo), as are the flowers

in the main border. It appears to me that orienting the rug with the arch at the

top is a perfect example of a lovely hypothesis ("The rug was woven for use as

an appurtenance in Moslem prayer") coming face to face with an ugly fact

("Nearly everything in it is upside down when it is oriented for use in prayer,

but rightside up if it was woven for decorative purposes") and the issue being

resolved by ignoring the fact.

Regards,

Steve Price

Posted by Yon Bard on 01-02-2003 10:22 AM:

Steve, I find looking at the architecture upside down is far more disturbing

than looking at the flowers upside down.

Regards, Yon

Posted by Filiberto Boncompagni on 01-02-2003 10:37 AM:

I like the explanation "it may make it more certain that the weaver will be

able to draw the area with the arch as desired".

Thatís why: if the weaver of

this rug had woven it upside down (which she didnít) she could have avoided the

mistake of hanging the lamp off center.

Regards,

Filiberto

Posted by Steve Price on 01-02-2003 11:32 AM:

Hi Yon,

I don't understand what you mean by the "architecture", but I

don't think the question of which orientation you or I find less visually

disturbing is the crux of the matter anyway.

Many of us have a prejudice

(by this I mean pre-determined notion, which may be correct) that rugs with

arches in their layout were woven for the purpose of being used for Moslem

prayer and that the arch is a mihrab. For simplicity, let's ignore the more or

less obvious exceptions like the Qashqa'i "milleflores" type and the Bezalel

synagogue rugs and, of course, my Kuba khorjin face.

Let's take the Kula

from the Ballard collection and try to see what it tells us about itself in this

regard. When oriented in one direction, it has an arch at the top. But why do we

think that is the top?

1. It's woven from the other end. Not compelling

evidence of anything, really. There seems to be no firm rule relating the

direction of the weaver's progress to the intended direction of viewing the rug.

2. There's a water ewer that's upside down if the arch is at the top.

3.

The flowers in the "arch" are upside down, and so are the flowers in the border.

To make a long story short, the rug has a number of elements in it that

have easily discerned tops and bottoms. Every one of them is upside down if we

place the "arch" at the top. On the other hand, all of them are rightside up

when it is oriented so that the "arch" is seen as a decorative design at the

bottom. While this is not conclusive, it does constitute an evidence-based

argument that the weaver intended the "arch" to be at the bottom. On the other

hand, unless it is assumed that the arch belongs at the top I see no basis for

concluding that it does.

Regards,

Steve Price

Posted by Yon Bard on 01-02-2003 12:12 PM:

Steve, it should be pretty clear what I mean by 'archuitecture.' since the

field (if viewed in the 'proper' way looks like a section of an endless

collonade with pointed arches and a textured ceiling, most reminiscent of

Moorish architecture in Cordoba and Granada. I have seen it hypothesized that

these designs came from spain via the Jews who were expelled in 1492.

I

think the direction of weaving on prayer rugs doesn't mean too much. I have

Beshir prayer rugs woven both ways.

As a prayer rug is used horizontally

on the floor, the concepts of 'up' and 'down' are not as meaningful as one might

think.

Regards, Yon

Posted by Steve Price on 01-02-2003 02:04 PM:

Hi Yon,

The architectural derivation of columns is more obvious on

many rugs than it is on the Kula from the Ballard collection, and on one of

those I would lean more in the direction you do with regard to interpretation.

While "up" and "down" have little meaning when the rug is on the floor, when

used for prayer the arch or mihrab is at the head end, so there is a direction

from which it is viewed. The head end, in that use. is reasonably referred to as

"up", the foot end as "down". When the columns are architectural and support a

representation of a ceiling, directionality is again reasonably called "up" and

"down".

Like you, I find the piece aesthetically more pleasing with the

arch at the top, probably because I don't pay much attention to the

representational details when I look at it.

Regards, and happy new

year,

Steve Price

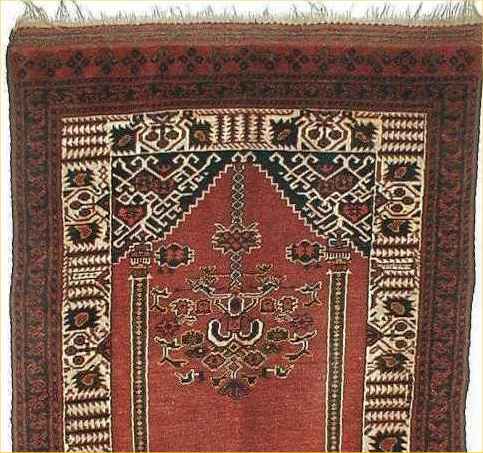

Posted by Chuck Wagner on 01-10-2003 11:26 AM:

Option 3

Hi all.

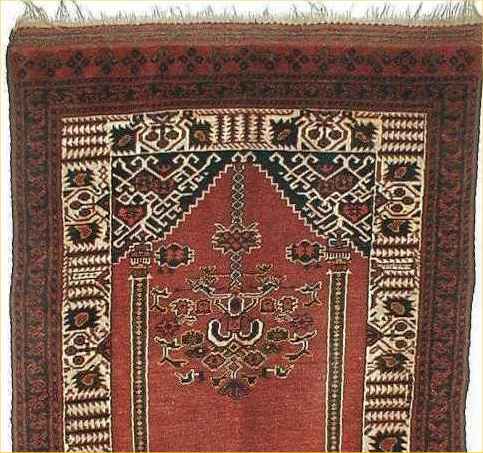

I propose that there is a third possibility for occasionally

weaving

prayer rugs "upside-down". An example is this 1950's-ish rug

from

Jangl Areq in NW Afghanistan:

I think it may be a "Light

end vs. Dark end" thing, where the

weaver recognizes that (in the case of a

prayer rug) the user

will almost always be viewing the rug from the bottom

and feels

that the rug will be too dark to really appreciate the

colors

and/or pattern if woven "normally".

This particular rug is

quite dark when viewed from the open pile

end, but quite nice when viewed

over the back of the pile. This

would be less important with pile clipped

very short, such as some

of the Shirvan rugs, etc.

Regards,

Chuck

__________________

Chuck

Wagner

Posted by Kenneth Thompson on 01-13-2003 06:42 PM:

Practical considerations

Dear All,

In the catalog text that accompanies the current exhibition

of Turkish carpets at the Washington Textile Museum, Walter Denny postulates

that niche prayer rugs were woven upside-down in order to assure that the most

difficult part, the "mihrab", was completed first. If the weaver ran out of

space as the warps contracted towards the top, she could finish with a straight

border. I don't have the text at hand or I would quote you Denny's more lucid

explanation.

If you don't have a copy of this publication, it is worth

ordering from the Textile Museum. It is well written and full of common sense

from an expert who has spent most of his life in the carpet and textile

field.

Regards,

Ken

Posted by R. John Howe on 01-14-2003 04:51 PM:

Hi Ken -

Good to hear from you.

Yes, the reason you give here

is the first one I gave at the beginning of this thread, but I certainly agree

that Denny explains it better than either of us.

Regards,

R. John

Howe

There also may be rugs out there with a

one-way field that were easier to weave upside down, but no one bothered to make

note of it.

There also may be rugs out there with a

one-way field that were easier to weave upside down, but no one bothered to make

note of it.