Posted by Richard Farber on 11-27-2002 12:33 AM:

Where did the motive go ?

Many thanks for the well researched and documented essay.

I

understood that the floral motive which you for the sake of continuity retain

the 'tuning fork' name appears in the carpets shown which were made before

1850. You see their 'root's in earlier textiles and carpets [although it would

be nice to see some images of the motive in earlier pieces]. Perhaps you or the

public have information as to what happened to this motive. What did it evolved

into. Did it just disappear?

thank you

Richard Farber

Posted by Guido Imbimbo on 11-28-2002 12:39 PM:

Floral form

Dear Richard and all,

in the Salon we state that the

"Tuning-Fork" is an elegant and effective rendition of a floral motive with

calyx, stem and opened petals. These floral motifs are organized along vertical

lines where also other simpler flowers appear as filling device along those

lines.

Alberto Levi believes that the vertical lines are derived

“from the shape of the watercourses” that would "have been

extrapolated from the early garden iconography".

While I agree that the

"Tuning-Fork" composition is rooted in the Persian garden iconography, I doubt

that the vertical lines are directly connected with the watercourses that have

been used in a specific and well known sub-group of "garden carpets" (see for

example plate 91 in the Sphuler book on the Berlin Museum).

I believe

that the vertical lines may represent just floral tendrils and actually along

these tendrils we can find some knots of different size that again recall

floral motifs.

Of course I am aware of the dangers and pitfalls of this

kind of "represantational" analysis of carpets design. I also reckognize the

limitation of exercises based on a simple "design" comparison that John Howe as

correctly pointed out in another post.

I just wanted pointed out one

typical feature of the early Persian floral iconography that is represented by

"repetitive" floral schemes. These schemes are constituted by flowers, shrubs,

etc. that are organized, with little variations, in a repetitive mechanism

often using grids, compartments or lattice frameworks. The rendition of the

"organizing" devices is explicitly floral and often recall often tendril forms.

See for example plate 107 of the same Berlin Museum book.

We know that

these repetitive floral structures had a vast influence in later carpets

production in many centres that go from Persia to Caucasus. The latest rugs

present an increasing geometricalization of the original scheme. In a previosus

Salon I even argued with Wendorf that the apparent geometric forms of some

Kurdish rugs are a particular interpretation of this original floral

frameworks.

I believe that the "tuning-fork" structure belong firmly to

the original Persian tradition. It is interesting to note that in the

"tuning-fork" rugs the repetitive framework is organized on vertical lines. The

"organizational" device would be represented by vertical tendrils.

Where

did the "tuning-fork" go?

Well, first of all in the Salon we argued that it

went to ... Group B carpets where the motif became more geometrical and rigid.

Secondly, we noted (see note 1 at the end of the Salon) that the

"tuning-fork" device is very close to a more simplified "trefoil" motif, often

organized in a lattice scheme, that is found in others Persian weavings.

An

example of the "trefoil" scheme is published in plate 295 of the ORAC book but

there are also other carpets in the Wendorf exhibition Kurdish carpets in

Washington that is listed in our references at the end of the Salon.

Finally there is a pair of Kurdish bags that belong to my friend Dante that

have been discussed on Turkotek a couple of years ago.

I know that this

is only a partial answer but I hope that it helps to the

discussion.

Regards

Guido

Posted by Richard Farber on

11-29-2002 12:54 AM:

Dear Guido Imbimbo,

thank you for the detailed reply.

I am

trying to understand the phenomena that you have described -- out of a body of

floral motives a new variant appears that is so different that researchers [or

dealers] have given it a non floral name. The motive appears in a limited

number of examples in a restricted geographic area and then within a very short

period of time disappears with seeming to have left any [or very very little ]

resonance in the continuing expression of Kurdish weavers let alone weavers of

other groups.

I have been trying to compare this to what I know of the

history of motives in music and have been thinking about closure motives. Yes I

can think of some motives that have come along been used in a small area and

disappeared - particularly in the middle ages. I have been thinking about why

this is so.

I wonder if you would be prepared to say something on why

the use of this motive did not expand in the Kurdish community let alone other

proximate groups and why it so quickly died.

I also would greatly

appreciate some images of the Persian motives that you think are those that

were the precedents of the motive in question.

Thank you

Richard

Farber

Posted by Guido Imbimbo on 11-30-2002 06:38 AM:

Kurdish Trefoil Carpets

Dear Richard,

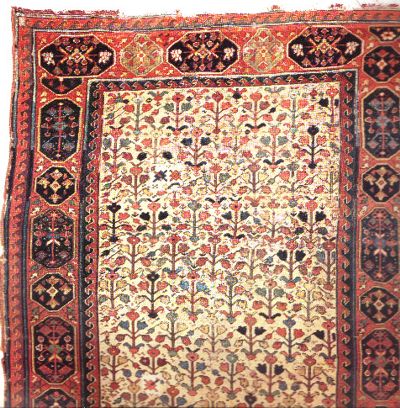

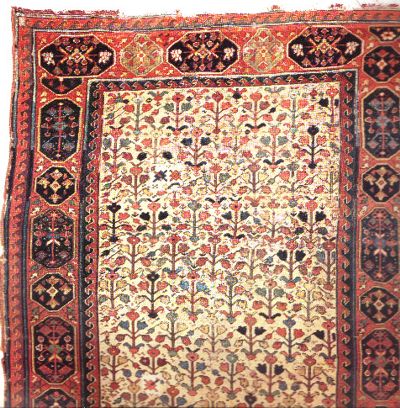

here I have included some pictures of three Kurdish

carpets that have been exhibited on October 23rd, 1999 at the Keshishian

Gallery. The rugs present an overall deisgn in the field with repeated floral

design that has been labelled "trefoil".

I believe the relation between

the "tuning-fork" motif and the "trefoil" design is very strong. My guess is

that the three "trefoil" carpets are somehow later than the rugs in the Group A

discussed in the Salon. The difference in the degree of sophistication in the

organization of the design and the execution of the details between the two

groups of carpets make me guess that the "tuning-fork" rugs in Group A are

older. Michael Wendorf may confirm or not this perception.

The evident

relation between the "tuning-fork" and "trefoil" rugs confirms to me that the

"tuning-fork" motif is definitely a floral one. I am convinced that the design

is rooted in the early garden/shrubs persian iconography that is organized in

repeated structure. In another thread John Howe have advanced the question if

the "tuning-fork" motifs can be seen as species of "animal trees".

Best regards

Guido

Posted

by M. Wendorf on 11-30-2002 10:11 PM:

Floral motif

Greetings:

I believe that my friend Guido must be correct when he

writes that "tuning fork" motif is a floral one and that it is part of a

Persian tradition (rather than, say, Kurdish). I tend to think of the vertical

lines as stems rather than tendrils.

I also agree with Guido that

Alberto Levi was not correct when he attempted to connect these stems or

tendrils to from the shape of watercourses ... extrapolated from the early

garden iconography. The Persian garden is a quite formal, even architectural.

No doubt, watercourses played a central role in the design of these gardens.

That said, I am not aware of any formal Persian garden plan involving the use

of vertical watercourses that approximate anything even remotely resembling

these vertical stems or tendrils. Moreover, there are well documented formal

garden carpets that quite clearly show these formal Persian gardens in some

considerable detail, none bearing any relationship to these stems or tendrils

that I can readily discern.

By the same token, there is quite clearly a

fairly large group of Kurdish carpets that have design motifs drawn from the

formal garden carpets, many of which were woven in Kurdistan, and the formal

Persian garden. Many of these rugs have fantastic color and wool. Whether this

amounts extrapolation or whether the motifs themselves are iconographic is

difficult to know for sure. However, I am quite certain that none of the rugs

Mr. Levi illustrates are earlier than the 19th century and that they are not

what one could fairly call Proto-Kurdish.

Guido is also careful to call

the floral tuning-fork motif as being part of the Persian design tradition

rather than more narrowly Kurdish. I think that this is also correct and a

small but important point. We might even say "Pan-Persian." I also think the

relationship to the "trefoil" motif is intriguing and part of the same

Pan-Persian tradition. I have not handled the rug Levi illustrated in his

article. But I have handled all the rugs Guido illustrates above and several

"tuning fork" rugs. In addition, I have had several related bagfaces including

one just like the pieces in the Dante collection. I cannot say that one group

is older than the other. Among the trefoil long rugs, the rug on the far right

in both illustrations seems very old - at least as old as any tuning fork piece

I know of. The other two pieces both have good age as well. One thing I am

quite confident of is that the borders on these long rugs is related to that

found on many formal Kurdistan garden carpets. I call it rosette and shrub. See

Spuhler plate 91 referenced by Guido as one example.

John Howe's idea

about the animal tree is an intriguing one that I had not considered and that

may be worth further exploration in connection with these motifs.

Thank

you for the Salon, Michael Wendorf

Posted by Patrick Weiler on

12-01-2002 12:18 PM:

You can't see the Forks for the Trees

Michael,

Is it possibly the branches of trees that Levi is

referring to when he relates the "tuning fork" to garden carpets, not the water

course itself?

Later versions of garden carpets seem to show tendrils

entering the "plots" of the garden from the main water courses. Earlier

versions show that these tendrils are actually trees with tendril-like

branches.

A later version is shown here:

http://www.hort.purdue.edu/newcrop/history/lecture22/06.html

The

tendrils enter the plots diagonally, then venture vertically, similar to the

iconography on the familiar Tekke Engsi discussed by John Howe in an earlier

salon. It is easy to suspect that, to Levi, these diagonal tendrils may have

represented not trees, but water coming from the main channel to irrigate the

plots of the garden.

This next link shows, at the very bottom of the page,

an earlier version of a garden carpet, with some of the trees entering the

plots in a diagonal orientation:

http://www.faculty.de.gcsu.edu/~rviau/islamicgardens.html

Most

of the trees enter vertically or horizontally, but only the diagonal type

survived in the later versions of garden carpets.

Patrick Weiler

Posted by M. Wendorf on 12-01-2002 07:16 PM:

garden carpets

Hi Patrick:

I do not know what Alberto Levi was referring to. He

wrote the following: "Another of the many patterns that have been extrapolated

from early garden carpet iconography is derived from the shape of the

watercourses, which are indicated by a motif that resembles a tuning fork. This

recurs on the three vertical axes that define the orientation of the

composition of a proto-Kurdish rug from the Sauj Bulaq area." Hali 70, page

92.

The best that I can come up with is that he was responding to the

watercourses in certain formal garden carpets in which the weavers attempted to

weave a pattern into the watercourses that can be understood as the water

moving through the watercourses. See plate 9, page 90 of his article. These

vaguely resemble the shape of the tuning fork motif. But it is also possible

that he was referring to branches, only he could answer this.

One

problem that Mr. Levi did not address but that I think must be confronted when

trying to link Kurdish carpets to garden carpets is to understand or decide

what gardens are being depicted. An allegorical garden, a garden in Kashan, one

in Isphahan, or one in Kirman? Another is who wove the formal Kurdistan garden

carpets and why? Here Mr. Levi seems to suggest that ex-Safavid court weavers,

possibly Kurds, went back to Kurdistan in the late 17th or early 18th century

and commenced what became an ongoing local village production of rugs with

garden and/or floral motifs in the Safavid tradition, but much simplified. If

so, it seems similar dispersions also occurred among other peoples and areas -

even among the Baluch.

These issues are emeplified by the links you

provided. Quite a bit of variety within a basic structure. In your last link

the Persian Garden Carpet is the well known Wagner Garden Carpet, Burrell

Collection, The Glasgow Art Gallery and Museum. Note the four-fold garden, or

four gardens in one, orientationwhich is the classical garden layout and

something not seen in the tuning fork rugs. This is a Kirman piece dated to

about 1750.

If anyone is interested in garden carpets you might

consider Hali Vol. 5, No. 1.

Regards, michael wendorf

Posted

by Guido Imbimbo on 12-02-2002 12:32 PM:

Searching for Tuning-forks origin

Dear All,

Richard Farber has asked at the beginning of this

thread to see some pictures of early Persian rugs that show the garden

iconography to which represent the root of the sub-group of Tuning-fork

carpets.

I am convinced that this linkage actually is discernable,

though it is not an obvious one and its is very difficult to identify. I just

hope to give a small contribution in this direction.

As starting point,

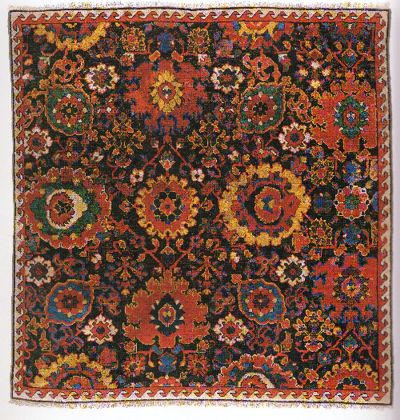

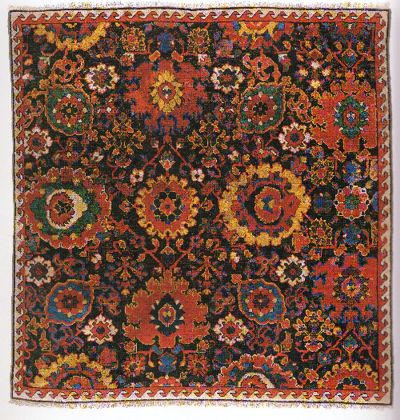

I prefer to focus to the early Persian “shrubs” rugs. This is a vast

term that includes many examples that differ in type, quality, age and origins.

Nevertheless, consent me to distinguish two groups of carpets.

1)

Compartments Shrubs Rugs

In these rugs, the shrubs, usually of small

dimension, are organized in compartment or lattice structure. Floral tendrils

often represent these connecting structures. The repeated small shrubs/bushes

in each compartment vary in some floral e color detail. Here I enclosed the

typical example is the Berlin Garden carpet (plate 107 of the Sphuler book).

This carpet takes origin by the Garden carpets mentioned by Michael Wendorf and

illustrated in Hali vol. V, No. 1 and that recall the structure of the elegant

gardens that were popular in the Persian courts. In the Berlin rug

simplification the watercourses have been omitted. It also important to

remember that there is also a group of early shrub rugs organized in the form

of lattice, some of them attributed to India (see Eskenazi book, plate

37).

2) Free-Field Shrubs Rugs

The size of

the shrubs represented in these carpets is much larger then the previous group.

Sometimes the dimension of the floral device can reach the size of a tree. The

details of the design can be very articulated. In the best pieces, it seems

there is an effort not to repeat the same forms but instead to maintain a high

degree of design differentiation. Note that in general in these schemes the

design does not include tendrils or other floral device that connect each

shrub. Here I enclosed a picture of a beautiful fragment (104x265cm) taken from

Hali Issue 39, page 98. There are also a number of others significant examples

that follow this design scheme, some of them attributed to the Kirman area (see

9th ICOC book, plate 55).

The organization of the floral devices in the

"Tuning-forks" rugs seems taking origin to both design structures illustrated

above. While the flower elements are not organized in compartment or lattice,

it is possible to identify in the bleu field, vertical grids that resemble

floral tendrils with small knots that looks flowers (see the direct scan of my

fragment). These tendrils connect the different floral elements represented in

the field of the rug.

At this point it may also useful to recall also another

group of early Kurdish carpets, which age probably is not very distant from the

Tuning-fork group. In the field of these carpets we find an all-over repeating

shrub pattern. Here I enclosed a picture of a Kurdish carpet (168x274cm) taken

from the John Thompson book (page 46) that is also commented in the Levi

article (page 89). I believe there is an interesting connection between the

pattern of the shrubs Rogers rug and the "Tuning-fork group" and between this

and the repeated "Trefoil" rugs in the Wendorf exhibition.

Finally, I enclosed a picture from a beautiful Sauj-Bulag

fragment published in the exhibition Sovereign Carpets in occasion of the IX

edition of the ICOC in Milan. In the beautiful harshang rendition of this

carpet it is possible to detect the presence of small bushes/shrubs that recall

the "trefoil" and the "tuning-fork" devices.

Best regards

Guido

Posted by Bob Kent

on 12-03-2002 09:38 AM:

'Proto-Kurd' = Ur- or Uber-Kurd?

Guys: Perhaps the 'Proto-Kurd' label was meant more as 'Uber-Kurd'

(i.e., height of) versus the 'Ur-Kurd' (i.e., firstever) that it seems to

imply? As used, 'ProtoKurd' subsumes some very different things. For example,

the fine tuning-fork rugs might be put in there, and Sotheby's waxed

ProtoKurdishly about another rug with the same major border and related shrub

field as my cut up bijar (reconstruction image below, it's minor borders are

maybe like the one in the open-field shrub rug above?). I assume the

construction of these 'ProtoKurdish' things is completely different?? .... see

you, B Kent

Posted by M. Wendorf on 12-03-2002 12:16

PM:

The Ur and the Ueber

Hi Bob:

The exact term used by Levi was "proto-Kurdish." I spent

years trying to figure out exactly what he meant by this term. I even asked him

a few times. Each time the answer was different and increasingly vague. Perhaps

I used the wrong methodology?

In his article, see page 87, Levi wrote:

"Among the several classical traditions of carpet design that appear to have

migrated from central and southern Persia to Kurdistan and then become

characteristic of certain classes of Kurdish rugs, the so-called vase carpet

group is of particular significance (reference to illustration 1, the

Gulbenkian vase carpet.). This extensive body of carpets, which encompasses a

great variety of designs, exerted a major influence on the development of a

family of relatively early Kurdish rugs, which I will call proto-Kurdish." Levi

also references Martin's description of dislocation and unheavels in the era of

Nader Shah. Page 85.

This leads me to conclude that Levi believes that

Kurdish weaving arose out of this dislocation and upheavel, in effect arising

in the 18th century. Moreover, that a variety of classical traditions

characterize Kurdish weaving with the Vase technique pieces exerting a direct

influence on the these so-called proto-Kurdish pieces. In this sense, it seems

he is arguing both that this dislocation and dissemination, if it occurred, is

the Ur and the pieces within this group with the most lustrous wool and most

saturated color the Ueber.

I think it suffices to state that I do not

share Mr. Levi's views of Kurdish weavings although there seems to be little

doubt that there is a substantial group, or family to use Levi's terminology,

of Kurdish carpets with very lustrous wool and deeply saturated colors that

have designs that seem related to Safavid era carpets. I would note that none

are structurally related to Vase carpets. I would also note that while of great

beauty, they make up only a small fraction of Kurdish weaving output over the

past 200 years.

Regards, Michael

Posted by Richard Farber on

12-04-2002 12:21 AM:

Dear Mr Imbimbo and Mr. Deschuyteneer,

there is a jarring

dissonance between your well researched and presented essay and the continued

use of the misnomer 'tuning fork'.

I was presented with a similar

problem in finding a catagory name for the niche form textile that I began to

describe in a previous salon. I did not call them 'prayer' embroideries because

I honestly believed that that was not the best catagory name for the knowledge

[or at least the speculations] available at that moment.

I believe that

you should find another name for the group and put the tuning fork in brackets

after the new name. Hopefully the new name will catch on and be some indication

of the contents of the group.

with most sincere regards

Richard

Farber

N. B. thank you for the images. They are a great help in

understanding.

Posted by Patrick Weiler on 12-05-2002 05:56 PM:

Motive Located

Where did the motive go?

Check out this

thread on Salon 35:

http://www.turkotek.com/salon_00035/s35t3.htm

There

are references to Afshar and Khamseh weavings sharing this design, which may

provide a road map of where this design went after leaving the purported Kirman

Vase rug region of southeast Iran. It went west, then turned north, following

the mountains, only to be located in hidden Kurdistan by Guido and Daniel,

intrepid explorers!

The tuning fork itself certainly seems to be the stem of a

floral device.

Patrick Weiler

Posted by Alberto Levi on

12-08-2002 12:54 PM:

Neither Ur nor Uber

Dear All,

I have been informed about this Salon by a friend that

visits this site quite frequently. I read the work by Guido Imbimbo and Daniel

Deschuyteneer, which I found very interesting, and read all of the comments

made subsequently. Since I have been quoted (and misquoted) a number of times,

I would like to take this opportunity to clarify a few points.

First of all,

the misquotes. Michael Wendorf's statement that he asked me a few times for an

explanation of the term 'protokurdish' is false. The only time we discussed

about this was at the recent ACOR at Indianapolis. There Mr. Wendorf gave a

talk about Kurdish rugs, where the common thread was that 20th century Kurdish

rugs are the heirs of a five thousand year weaving tradition. His criticism of

the term 'protokurdish' was that it is a misleading term, since clearly Kurds

were weaving rugs certainly before the beginning of the nineteenth century. My

reply was that I never disputed this: as a matter of fact, I tried to trace

some very ancient origins in some Kurdish typologies and addressed this both at

a convention on Kurdish rugs held at the Textile Museum in Washington and on a

paper published thereafter on 'Ghereh'. I can give further details about this

to anyone interested. The term 'protokurdish' attempts at defining a cluster of

weavings with common structural and chromatic features, which also share a

common lineage in that they seem to re-interpret a number of patterns that are

characteristic of certain Safavid typologies. Furthermore, these 'protokurdish'

rugs seem to be immediate ancestors to many nineteenth and twentieth century

Kurdish rugs from west and northwest Persia.

They represent a kind of bridge

between the earlier court weaving tradition and the post-Safavid establishment

of a village weaving tradition.

Which brings us to the subject of 'tuning

forks', or the quotes. Indeed I see a strong resemblance between the 'tuning

fork' motif as it appears on the Sauj-bulagh rugs illustrated in this work and

what I call 'the shape of the watercourses' on Safavid Garden carpets (such as

the Aberconway Garden carpet in the Kuwait National Museum, for example). The

directional floral motif is most probably a result of an extreme stylization of

the design of some earlier 'shrub' rugs (some of which are illustrated in Guido

Imbimbo's post), and in that sense it is probably a hybrid design.

Nevertheless, the directional shrub design is represented on a different

Sauj-bulagh typology (the Rogers Thompson rug, illustrated both on my 'Hali'

article and on Imbimbo's post), and therefore should be seen as independent

from the 'tuning fork' type.

Common to all the rugs belonging to the

'tuning fork' sub-group is a repeating unit composed of a central seven-petaled

flower flanked by a pair of four-petaled flowers in contrasting colour. From

each of these four-petaled flowers sprout a three-petaled flower. This

blossoming unit 'rests', if you will, on the cup of the 'tuning fork' motif.

Could it be possible that the designer of this type wanted to synthetize both

the representation of the flow of water on Garden carpets and that of the

so-called 'islands' - from which blossom flowering trees (see for example the

'islands' on the Davis Garden carpet fragment in Metropolitan Museum of Art,

N.Y., published in Dimand & Mailey, fig. 117, p. 85)?

Best

Regards,

Alberto Levi

Posted by M. Wendorf on 12-09-2002 06:33

AM:

protos

Greetings to all:

Welcome to Alberto Levi on this Board. As some

of you may know, Mr. Levi has made numerous contributions to the rug world

including his service as chair of the local committee for the ICOC conference

last in Italy. In addition, Alberto has long been a promoter of Kurdish

weavings and has documented several rare types of Kurdish weavings over the

last years.

This Salon references Alberto's article in Hali 70, Renewal

and Innovation - Iconographic Influences on Kurdish Carpet Design. In his

article, Mr. Levi coined the term "proto-Kurdish" and attached it to four rugs

illustrated (among numerous others) within the article. All four of these rugs

were attributed to "SaujBulaugh". Two of these carpets were identified as being

part of Mr. Levi's collection. For precision and consistency, I continue to use

the original termand spelling of "proto-Kurdish." However, I think it is

preferable in English to use Sauj Bulaq rather than SaujBulaugh and do so here.

In fact, both spellings refer to a town that today is Mahabad. Sauj Bulaq was

an important Kurdish town and Mahabad remains so today.

Mr. Levi

refences some misquotes. No one here wants to misquote him or anyone else. In

one instance, Alberto states that my statement that I asked him "a few times"

for an explanation of the term proto-Kurdish is false. This is a strong word,

so I will respond. I attended the Textile Museum conference devoted to Kurdish

rugs referenced by Mr. Levi. In fact, several of what Alberto calls my 20th

century rugs were used to illustrate the lectures and discussion. I recall a

discussion of proto-Kurdish even then. I also recall exchanging emails with

Alberto in 1998 or 1999 in which the subject was raised. In each case, I recall

discussions about the use of the term proto-Kurdish. But perhaps I am mistaken.

In any event, we can discuss it now.

Proto is derived from the Greek

protos. Protos is generally understood by me to suggest the earliest or first

in time, the first formed. What Bob Kent referred to as the Ur. In language and

science it can have more specific meaning, but it is consistently used in the

context of "first formed". In his post, Alberto writes that proto-Kurdish as

used by him "attempts at defining a cluster of weavings with common structural

and chromatic features, which also share a common lineage in that they seem to

re-interpret a number of patterns that are characteristic of certain Safavid

typologies." (By typology I understand Mr. Levi to mean some systematic

classification such as the so-called vase structure in which all the members of

the type or class share an assymmetric knot and a depressed back). "Futhermore,

these proto-Kurdish rugs seem to be immediate ancestors to many 19th and 20th

century Kurdish rugs from west and northwest Persia."

I see several

issues arising from this explanation and the original article. First, if this

cluster of weavings share common structural and chromatic features what are

they? Mr. Levi provided no structural or chromatic analysis of any of the

pieces he illustrated or discussed in Hali 70. So far as I recall, the only

structural discussion was found on page 87 wherein we are told:

"Most

of these early proto-Kurdish carpets are characterised by a lustrous,

symmetrically knotted woollen pile. In many cases they have rust colored

wefts."

Based on this conclusion, he refences Eagleton and concludes

this group comes from Sauj Bulaq. Id. I do not believe words like "most" or "in

many cases" and the scant structural information provided is suffient to talk

about a typology much less a label as grand as proto-Kurdish.

The same

is true for the common chromatic features. What exactly are they? Of the four

pieces illustrated in Hali 70, two are woven on an ivory ground and two others

on dark grounds either a dark corrosive brown or something else. All I recall

being written on this issue is the observation that:

"The coloured yarns

employed for the pile of these latter rugs is extremely saturated, and are an

indication of the well-known competence of the Kurds in the art of dyeing."

Page 87.

In my view, this hardly amounts to common chromatic features.

Moreover, as Mr. Levi points out in his footnote, dyeing was largely carried

out by Jews during the relevant period. So what exactly does the observation of

saturated dyes have to do with the argument that these rugs, even if we assume

they form a single group based on other common features have to do with them

being Kurdish or proto-Kurdish?

And that, it seems to me, is the real

issue. What makes these rugs protoanything? Alberto's observation is that the

rugs he calls proto-Kurdish (and which I would simply call rugs with floral

motifs interpreting Safavid patterns or designs) must be the ancestors to a

larger group of carpets that also interpret Safavid era patterns or designs.

This is apparently because he believes the four rugs he illustrates are older

than most. Well, I think the most one can say is what Alberto adds in his post

- "they form a kind of bridge between earlier court weaving and the

post-Safavid establishment of a village weaving tradition." But even this (an

Ur limited to "village weavings") is a can of worms. We cannot really say

whether or not village weaving or Kurdish village weaving existed during,

before or arose only after the end of the Safavid era. Mr. Levi's article

offers no insight or new information on this question other than to surmise

that weavers may have dispersed into Kurdistan after the fall of the Safavids.

In addition, the article and use of the term proto-Kurdish completely

ignores a non-village or tribal weaving tradition among Kurdish groups that I

understand Alberto himself believes may well have existed.

I have

nothing to add to the discussion/use of tuning fork to describe the motif. I

still find it to be a floral stem. But Alberto's view is clarified.

I am

not familiar with Alberto's article in Ghereh that attempts to trace some very

ancient origins of certain Kurdish weaving types and do not recall this

specifically from the TM lecture either. I hope Alberto will expand on or at

least summarize his ideas on this. Alberto refences a talk I gave at ACOR which

was also the subject of a previous Salon - I believe it was #88. I will allow

that to speak for itself except to point out that I refer to 6000 years of

weaving history, not 5000.

Thanks in advance to Alberto and the prospect

of more discussion and clarification of our points of view.

Regards,

Michael

Posted by Alberto Levi on 12-09-2002 08:59 AM:

Proto-Kurdish

Dear All,

during the last few years the term 'proto-Kurdish' has

been used in many instances, more often on auction catalogues. My original

intention was that of isolating a structurally and chromatically consistent

group of weavings, and placing it in a time line with respect to what existed

before and especially to what developed later. From a structural point of view,

all of the proto-Kurdish rugs of the Sauj-Bulagh type that I examined in person

have an all-wool foundation,with natural wool warps and almost always two

shoots of very fine rust colored wefts, a fine knotting with very little to

almost no warp depression, and a soft pliable handle. I never recorded any

precise data on these, but all of these features gave me the clear impression

that we are dealing with a structurally consistent group. The palette of all of

these rugs also seems to be very consistent, with very similar shades of

yellow, red, light and dark blue and aubergine often on a dark brown

background, more rarely on a yellow background and very rarely on an ivory

background. In every case the colours are clear and vibrating, with a

translucent quality that gives almost the impression of looking at a glass

mosaic.

However this is limited to the Sauj-Bulagh group. Since publishing

my article, many other types of proto-Kurdish rugs came to light, some with

completely different structures and colours. But this could be the subject of a

new Salon.

In any case, my 'proto-Kurdish theory' does not imply that there

wasn't any village and tribal weaving carried out by the Kurdish people of west

and northwest Persia prior to 1800. The problem is how to identify them. I have

attempted at connecting the hooked lozenge design of the Jaf tribe, as well as

the use of offset knotting, to some early Turkish rugs possibly from eastern

Anatolia. This was part of my contribution at the Textile Museum Kurdish rug

convention (Michael: was year was it?) and also part of an article on Kurdish

rugs that I wrote for 'Ghereh'. I have since 'forgotten' about everything

Kurdish, but perhaps this Salon will motivate me enough to start working again

on this fascinating subject.

Best Regards

Alberto Levi

Posted by Steve Price on 12-09-2002 09:45 AM:

Hi Alberto,

If you would like to prepare a Salon essay on the

proto-Kurdish designation, I will be glad to run it. As you may know, we open a

new Salon on the 24th of every month, and barring anything unforeseen I can put

this into the first slot after I receive it.

Would you let me know if

you are willing to do this? If so, I will ask people to leave the subject of

proto-Kurdish for the moment rather than embark on a more detailed discussion

of it within the context of Guido and Daniel's Salon.

Thanks, and

welcome to our forums.

Regards,

Steve Price

Posted by

M. Wendorf on 12-09-2002 02:07 PM:

Kaleidoscope of Kurdish rugs

Greetings All:

Alberto, the TM conference called Kaleidescope of

Kurdish Rugs must have been '95?

Steve, I would prefer to leave the

subject of proto-Kurdish rugs forever. More realistically, I think it would be

of broader interest to ask Ghereh if Turkotek can use Alberto's article there

as the basis for a Salon. We have previously had some discussions of the Jaf

hooked lozenge and offset knotting; the connection with old Turkish rugs - are

we talking rugs from Divirgi? - could be great.

Regarding isolation of

rugs with common structural and chromatic features, I am all for it. However,

isolating a group of Kurdish rugs on the basis of all wool foundation, natural

wool warps, and two shoots of rust colored weft with a flat back and pliable

handle includes many different kinds of Kurdish rugs in my experience. We have

discussed here at length about what we might call a traditional Kurdish weave -

two ply natural or ivory warps, flat back, wool or wool with animal hair for

foundation, pliable or floppy handle with glossy wool, mulitiple wefts of

various colors but often reds, corals, rusts and browns etc. - not much

isolated from the general description supplied by Alberto. And I have seen rugs

seemingly in the same group Alberto discusses with coral and red wefts.

Likewise isolation based on general palette consistencies seems

dangerous. In my view, a more detailed dye analysis is necessary before we can

even start to isolate a group within the production of these rugs with floral

designs interpreting Safavid models.

Finally, the timeline that was

Alberto's goal beyond isolation of a group is always speculative. Alberto

thinks his rug is 1800 and mine 1920, I think the opposite. Who is right?

Probably neither. This is not to say that someone like Alberto who has handled

a lot of these rugs cannot get a feel for such a timeline, it is just that we

can never really know because there are no anchors or base from to start with

any real confidence. Great dyes continued to be made after 1800 and inferior

ones prior to 1920.

Personally, I doubt there are any real close

structural or chromatic consistencies sufficient to start narrowly isolating

groups of these rugs and establish a typology. In any event, I think side and

end finishes would have to be considered as well. In the end, it seems likely

that several small shops were responsible for these rugs, however organised,

and made them over some period of time, perhaps even 100 years or more. And we

likewise need to consider that similar enterprises seem to have arisen in a

variety of areas across Persia, not just Kurdish areas.

I for one do

hope that Alberto will host a Salon.

Regards, michael

Posted

by Steve Price on 12-10-2002 09:10 AM:

Hi All,

Alberto sent me a message saying that he will try to

prepare a Salon on proto-Kurdish for our January 24 slot. This being the case,

I ask that we suspend discussion of that topic for

now.

Thanks,

Steve Price

Posted by M. Wendorf on

12-12-2002 03:34 PM:

'93

Alberto:

I went and found my notes from the TM conference.

Believe it or not, the dates was October 15-17, 1993. The topic of your lecture

was "Classical Kurdish Rugs from Persia and Anatolia." My notes, such as they

are, make no direct reference to the Jaf lozenge and the only reference to

offset knotting is to the effect that if there are early Kurdish rugs, offset

knotting would be one way to identify them. I believe you showed some slides of

Anatolain rugs with offset knotting that might be Kurdish including one

fragment with big hooked devices in the field. Perhaps this piece was your

connector to the Jaf lozenge?

My notes also state that in 1993 you and

Christina Bellini were working on a book on Kurdish rugs, what happened to that

project?

Best, michael