The Salon du Tapis d'Orient is a moderated discussion group in the manner of the 19th century salon devoted to oriental rugs and textiles and all aspects of their appreciation. Please include your full name and e-mail address in your posting.

by R. John Howe

And in 1973, the first engsi attributed with some stability to the Salors appeared at auction.

There are currently ten Salor engsis known. So far there are no known

engsis attributed to the "eagle group."

What size

variations are there?

I'm going to deal with width and

length separately here. First, width.

The Ersari lady's indication

that she thought engsis often were placed on the inside rather than the outside

of the tent door attracted Peter Andrews' attention and reminded him of a

pattern he'd seen while collected engsi width measurements in some of his

research.

He said that as he recalled, the typical width of a Turkmen

trellis tent door was about 120 cm and perhaps less and that to fit neatly the

engsi should be narrow enough to permit it to be tucked under the tent felt at

the top of the door. Peter's remembrance was that some Ersari engsis were quite

wide and if they could not be tucked in the desired way that might be a basis

for conjecturing that they were placed on the inside of the tent door. So

despite the fact that the only picture we have on an engsis in use shows it on

the outside of the tent opening, width might be a basis for suggesting that

some engsis were hung on the inside since they would be too wide to "tuck" as

needed into the outside door opening.

This width idea was too inviting

not to play with and so I pulled out quite a few rug books and listed widths of

engsis given by tribe. I have a table with this data on over 100 engsis, but

I'll just summarize my findings here.

The Tekkes came closest to

meeting the 120 cm requirement. I encountered 30 published Tekke engsis. The

widest was 137 cm. The narrowest 107 cm. 9 of them exceeded 120 cm.

Salors (from Pinner's Hali article) varied between 123 cm and about 129 cm.

I encountered 11 Saryk engsis in my books. The widest was 152 cm. The

narrowest was 116 cm. Only two of them were under 120 cm and several were 145

cm or above.

There were 31 Yomut engsis in my books. The widest was

151 cm. The narrowest was 110 cm. Only 5 were under 120 cm. Nine were 136 cm or

above.

There were 38 Ersari engsis. The widest was 163 cm (a quite

modern piece in Parsons). The narrowest was 96.5 cm. Only 4 were 120 cm or

narrower. Both the widest engsi encountered in my search and the narrowest were

in the Ersari group.

There were 5 Chodor engsis. The widest 130 cm;

the narrowest 122 cm.

There were 3 Arabatchi engsis. The widest 142

cm; the narrowest 132 cm.

There was one engsi attributed to the Kizil

Ayak; 109 cm wide.

This leads me to wonder whether the door sizes on

Turkmen trellis tents might not vary somewhat and whether the estimate of a

likely max of 120 cm might be too narrow. The Yomuts with which Peter Andrews

did most of his field work often exceeded this max.

Engsis that are

estimated to be older do seem often to be narrower. But this was not

necessarily true for the Saryk pieces. Ersaris that we would likely estimate as

more recent do seem to get noticeably wider.

It's not as clean a

relationship as I had hoped for but it was useful to do.

Now length.

Pinner's Hali, 60 is my source for Salors. There were seven known then.

The longest was 193 cm. With most of them in the 190s and 180s. There is one

that is quite a bit shorter at 160 cm.

I recorded 11 Saryk engsis

lengths. The longest was 214 cm. The shortest was 152 cm.

I had 30

Tekke lengths. The longest is 183 cm. The shortest piece not seriously

fragmented for length was 129 cm.

In 31 Yomuts lengths, I found the

longest was 185.5 cm; the shortest was 146 cm.

There were 38 Ersari

lengths. The longest: 246 cm was the longest engsi length I encountered. The

shortest unfragmented Ersari piece was 127 cm, also the shortest engsi among

all those checked.

There were five Chodors. The longest was 223 cm

(much longer than the others). The shortest was 147 cm.

There were

three Arabatchis. The longest was 195 cm. The shortest: 132 cm.

There

was one engsi designated "Kizil Ayak," with a length of 165 cm.

So,

lengths of engsis vary quite a lot too. I do not see any implications of these

differences in lengths that approximate wthat Peter Andrews has suggested for

widths.

For those who like to relate width to length, Pinner provides

a little table of averages.

Here it is in large part, re-sequenced in

the tribal order I have used above, but without any Arabatchi:

Salor 6

pieces; mean length/width = 1.46

Saryk 16 pieces; mean length/width =

1:21

Tekke 40 pieces; mean length/width = 1:21

Yomut 36 pieces; mean

length/width = 1.28

Ersari 21 pieces; mean length/width = 1:29

Chodor

11 pieces; mean length/width = 1:26

Kizil Ayak 9 pieces; mean length/width

= 1:39

In this table, the average Salor length over width relationship

is a clear departure from most of the others, and the Kizil Ayak is also, but

to a lesser degree.

What design variations have

been noted?

At a more general level, there are engsis that

have the "hatchli" (cross-like) layout.

And those that emphatically do not.

There are some with clear arch devices in their designs.

And some without.

Some engsi signal their membership in this format group with some clarity.

With others we need to rely on indicators like size, and a distinctive border and the presence of an elem.

And there are even subtler instances in which we may sometimes be on shaky ground.

There are some tribal patterns and tendencies in engsi designs.

Salors do not show mihrabs. Neither do many Yomut engsis but there are also a

goodly number that do. Tekke and Arabatchi engsis with mirhabs are reputed

always to exhibit only one, but Jourdan includes one Arabatchi engsi (Plate

206) with four.

Some more minute analyses of engsi designs have also

been undertaken.

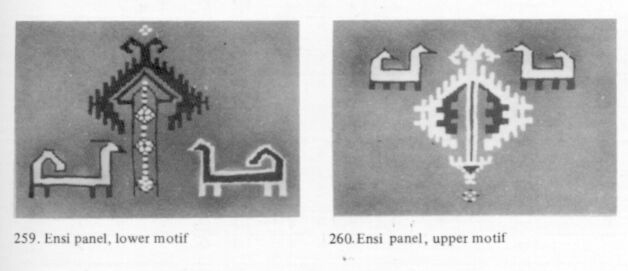

In Turkoman Studies I, Robert Pinner and

Michael Franses examined 110 Tekke engsis and identified a subgroup they

labeled "animal tree engsis." There were only 13 such pieces then. The main

distinguishing feature of this group was a panel in the lower part that

exhibited repeatedly a device composed of a "tree" form, flanked on both sides

by "animal" forms.

Similar devices appear on a group of asmalyks they had also examined

and the animals resembled those seen in "tauk naska" guls.

Subsequently in Hali, 60, Pinner undertook to analyze the designs in the seven

Salor engsis known at that time. Despite the small number of specimens, Pinner

felt he could discern two distinct groups, "Type A," and "Type B." He presented

a detailed analysis of the differences.

Do the

designs in engsis have symbolic meanings? If so, do we know what they

are?

At a most obvious level, the existing literature has

suggested that the "hatchli" format with its "cross-like" shape can be seen to

mimic the panels in many wooden doors. Some have also suggested that the

"hatchli" design denotes a kind of "garden."

In his "Turkoman"

volume, Uwe Jourdan points out that while the Turkmen tribes converted to

Islam, their earlier shamanistic beliefs still exerted considerable force in

their lives. He admits that the meanings of many symbols has been lost, but

then says about the engsi: "…With this in mind, it is possible to offer an

interpretation of those ensis with the "cross" (so-called hatchli) design. This

design can be said to reflect the idea of a cosmos with a tree at the centre of

the earth, the latter "represented" by the design found in the lower elem

panel. The four separate fields created by the cross-shaped

composition…represent the cardinal points, the hook-like motifs,

reminiscent of candelabra, within them representing the various spiritual

levels though which the soul most pass…"

Can

engsis be distinguished from Turkmen weavings that seem more likely to have

been "prayer rugs?"

Well, at a minimum there seem to be a

number of Turkmen rugs that seem clearly to have prayer-rug-like designs and

that seem also not to be engsis. Here are a few:

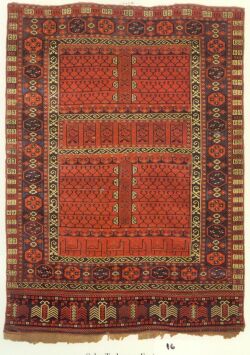

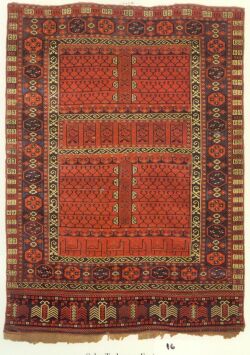

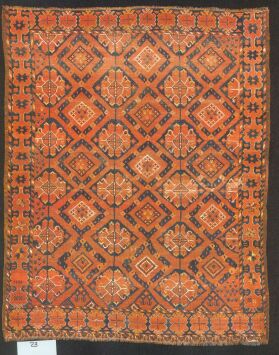

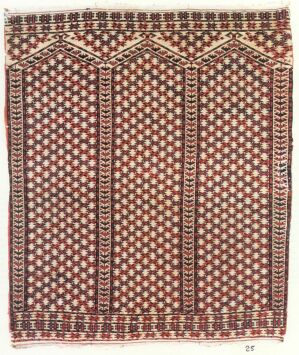

A Tekke

example:

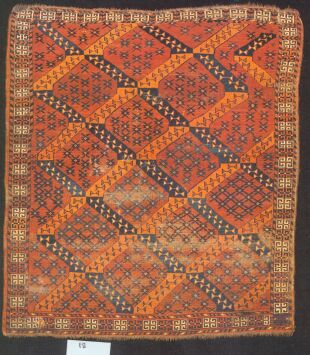

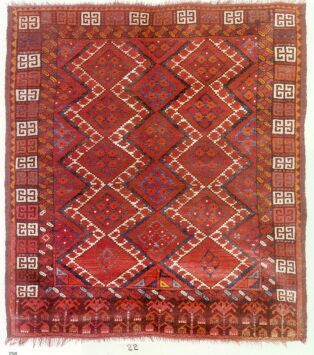

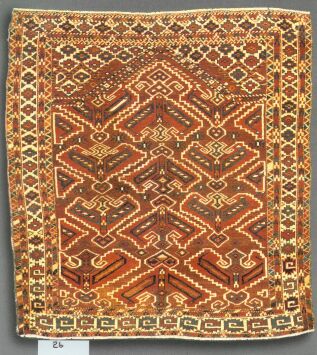

A Yomut:

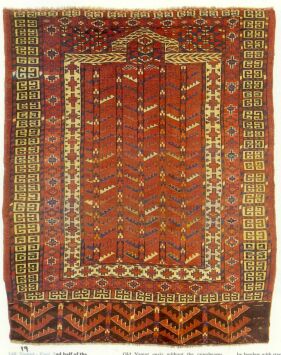

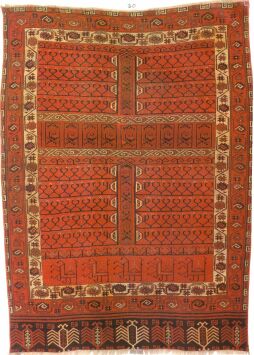

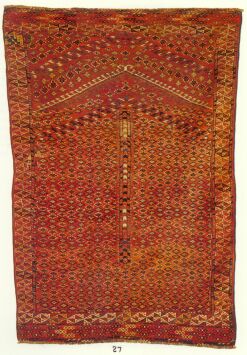

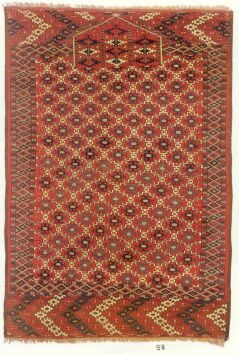

An Ersari:

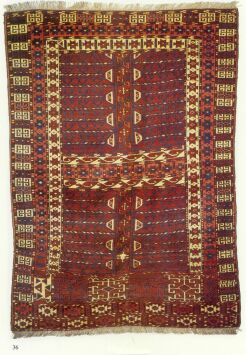

And a Chodor:

So there do seem to be Turkmen "prayer rugs" distinctive from the

engsi format.

About how old are engsis that seem to

attract collector interest?

One is tempted to say "Not as

old as the collectors would like." But the truth is that dating is extremely

difficult in the period in which most of the Turkmen material we have seems to

have been made. Yes, there has been some carbon dating and, without getting

into that debate, there do seem to be some Turkmen pieces much earlier than we

have thought. I do not know if any engsis were in the group that were carbon

dated.

But it still seems most likely that most of the Turkmen

material that has been collected was woven during the 19th century and the

early 20th. Collectors love to say the phrase "perhaps before 1850," but that

is sometimes unduly applied to almost any piece without synthetic dyes.

Many of the engsis that are estimated as older (perhaps first half of the

19th century) do, with some exceptions seem to be narrower. It would be

fascinating to discover the measurements of enough, say, Tekke or Yomut,

trellis tent door widths to permit us to apply Peter Andrews' notion that to be

neat engsis would have to be narrow enough to tuck into the top of the felt

door opening. This might let us identify those pieces in the engsi format that

could have been used on the outside of door opening.

Here is what

Peter Andrews said in our most recent email exchange:

"…The use of

engsis, as I suggested, is a more difficult subject, as, so far as I know, they

have not been used since the 1920s, and that means hardly within living memory

any more. My information on the Yomut use came from my best informant, in 1974,

who unhesitatingly explained the combination of qapiliq inside and engsi

outside the door frame. I regard it as entirely reliable, and it is of course,

reinforced by the British Boundary Commission image, and especially the fact

that the felt door flap is rigged with its ornament to the outside (the back is

a cane mat), just like those of the Qaraqalpaq, Qazaq and Qirgiz. This should

not really be in doubt. I suggested that the engsi should be tucked in, to look

neat, since this is what is done with felt door flaps among all Turkic peoples,

and Mongol ones too: in fact among Qazaq and Qirgiz the flap is prolonged for a

metre or so above the lintel in a long tongue, which is visible inside the

dome, and consequently decorated.

I have not yet had time to look up

my data on door widths. Believe me, we measured scores of Yomut tents in the

1970s, to establish the norms, so there again there should be no dispute. I

have had access to only a few Ersari ones, however, and Tekke. I would not

expect them to be different in principle, as they are governed by the same

constraints: the wider the door, the weaker the wall frame. Furthermore, the

door frame is of a similar width among all Turkic and Mongol peoples: only in

some ambitious cases is there a lateral extension on either side (such as the

monastery tent at Gandan in Ulan Bator). Anyway I shall look the dimensions

out, though an extensive survey will have to wait…"

But

enough of my thoughts, what do you think we can say about the engsi?