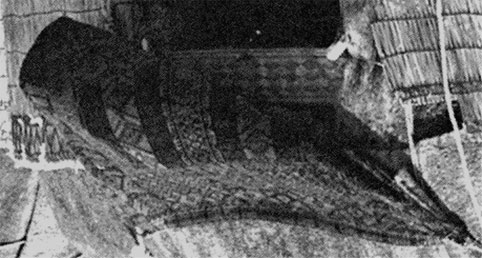

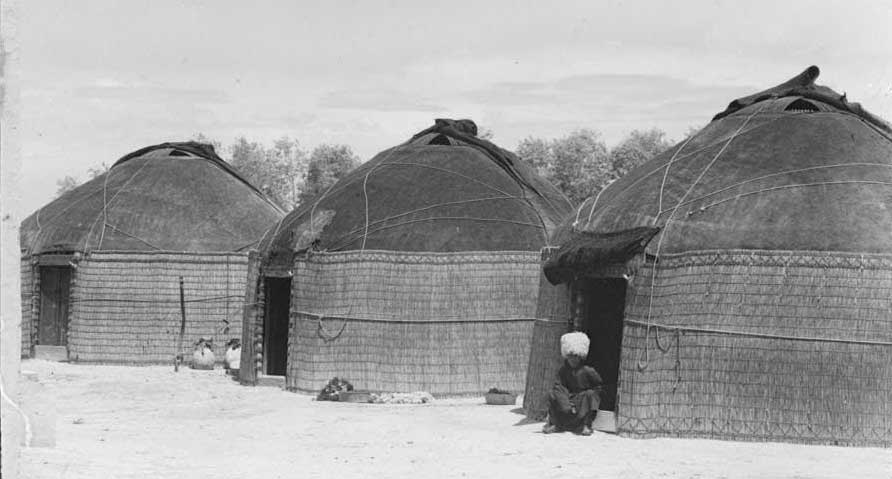

Posted by Steve Price on 08-24-2002 09:07 AM:

Did the engsi hang inside or outside the yurt?

Hi People,

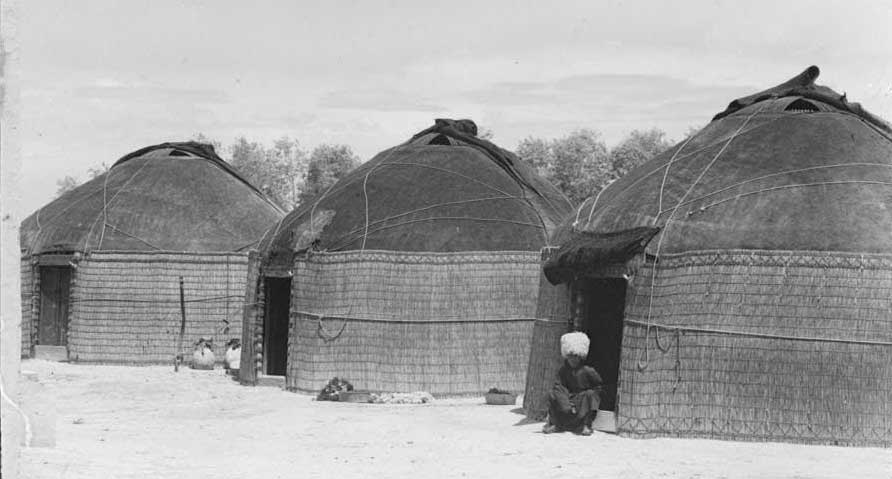

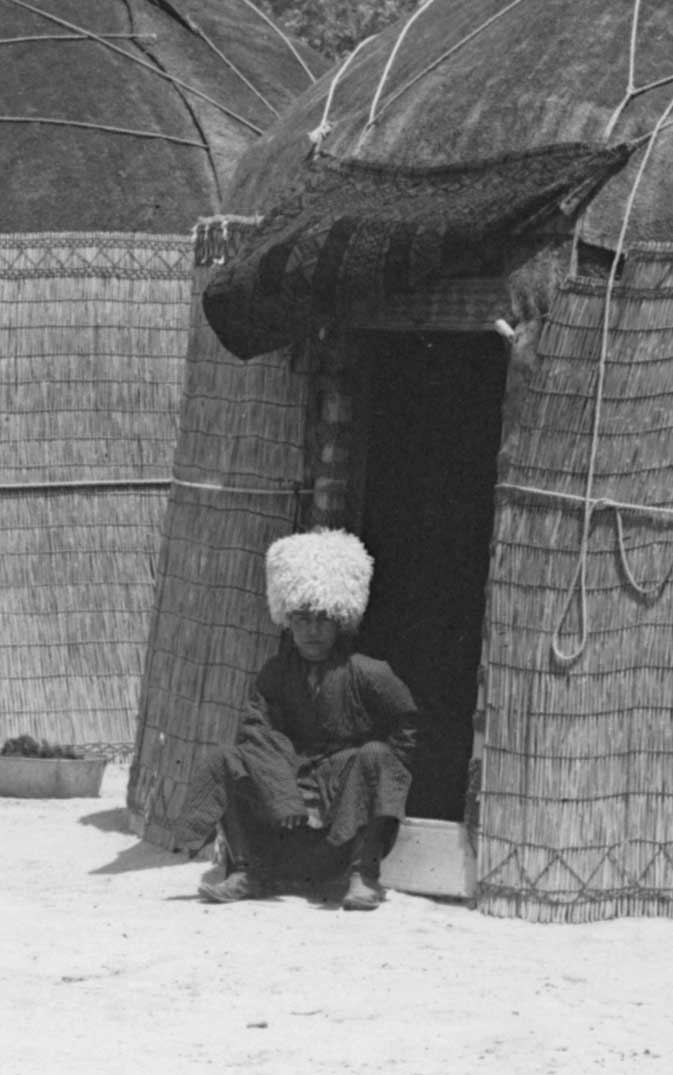

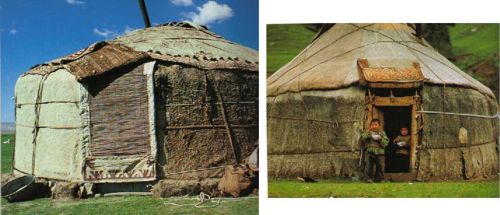

Here's a photo of a Kazakh yurt, taken in

1937.

The engsi is clearly shown, rolled up at the entrance. If

you look carefully, you can see that the roll is halfway in and halfway out of

the yurt, so when it was unrolled, the edges of the engsi would have abutted

the edges of the felt outer covering of ther tent. That is, it was neither

inside nor outside, just as the door of a modern house is neither inside nor

outside.

The source of the photo is Peter the Great's Museum of

Anthropology and Ethnography, St. Petersburg. I scanned it from Nomads of

Eurasia (Basilov and Zirin, eds), p. 99.

Regards,

Steve

Price

Posted by Robert Alimi on 08-25-2002 10:33 AM:

Hi Steve,

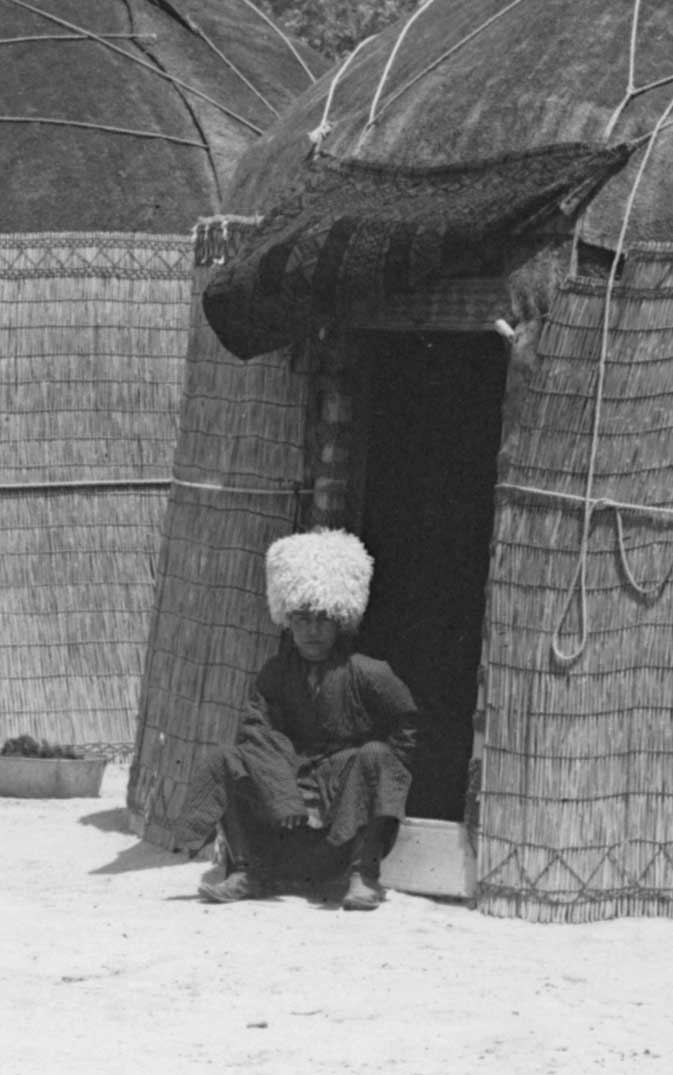

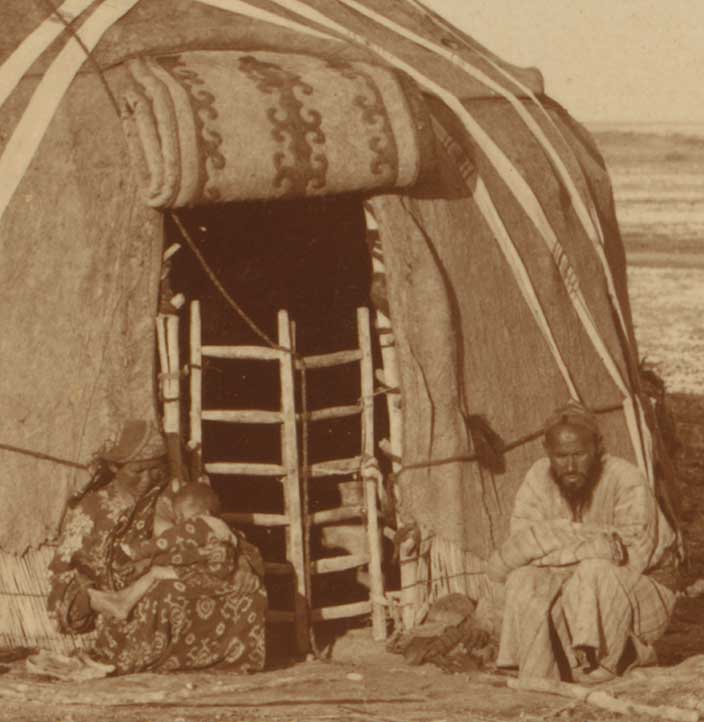

Here are some additional images. As I recall, these

photos were taken around 1910.

From the images, it appears that these engsis hang

outside the doorframes. Although it's really hard to tell from the photos, 2

photos appear to contain pile weavings, while 1 photo contains a textile that

is felt work.

Regards,

-Bob

Posted by Yon Bard on

08-25-2002 11:22 AM:

Bob, any info on where these photos are from?

It is noteworthy

that while Steve's ensi fits neatly in the door, Bob's are just slung from the

roof and don't need to obey any strict size constraints.

Regards,

Yon

Posted by Robert Alimi on 08-25-2002 06:58 PM:

Hi Yon,

I'm pretty sure that these photos are part of the

Prokudin-Gorskii Collection from the Library of Congress. I had saved these

images to my own computer some months back. I can't put my finger on the

specific source URL just now, but a starting link is:

http://frontiers.loc.gov/intldl/mtfhtml/mfdigcol/aboutpg.html

As

I recall, the photos are just tagged as "Central Asia", without any specific

information for each photo.

-Bob

Posted by Kenneth Thompson

on 08-25-2002 10:14 PM:

Dear All,

From all that has been said and written, it seems safe

to say that the Ensi (or at least a door flap of whatever name) hung on the

outside of the oy or yurt. The second picture that Bob posted is the first that

I have seen that may show a pile door flap. Every other instance that I have

found has shown a felt door flap, but these have been almost always on Kirghiz

or Kazakh dwellings. The Kirghiz equivalent seems to have been the Eshiktish

which by derivation was hung outside the oy. (Eshik=threshold, tish (or

dish)=outside.) Given the special nature of pile carpets, it seems unlikely

that a pile ensi would have been a permanent fixture on the outside of

structure exposed to harsh weather. It would make sense for it to be a special

occasion piece put up to welcome a bride or important visitor.

Another

possibility: could there have been two door flaps, a felt one on the exterior

and another interior one hung for special occasions? Or used as a tent divider

on special occasions? Any ithoughts?

Best regards,

Ken

Posted by Robert_Alimi on 08-26-2002 03:12 AM:

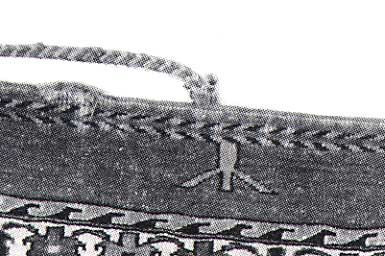

For what it's worth, I was able to locate the original images at the

Library of Congress website. I downloaded the (very large) tiff files and have

cropped the photos to focus on the doorways. Here are the close-up

images:

-Bob

Posted by Filiberto Boncompagni on

08-26-2002 06:21 AM:

Thanks for the pictures, Bob.

The door flap in the first close-up

looks definitely a pile weaving.

One should suppose that during daytime

the engsi was kept in that way.

One should thus expect engsis having the

upper part more discolored by sunlight…

This doesn’t seems the

case - unless collectors’ engsis where never used or had very fast colors.

Regards,

Filiberto

Posted by Steve Price on 08-26-2002

06:30 AM:

Hi Filiberto,

Actually, if the ensi was kept rolled up or folded

above the doorway during the day, it's the back that would fade from

light exposure; specifically, the part of the back that was outermost when

rolled up (the area near the bottom of the ensi). Sadly, few photos of ensis in

exhibitions, books, auction catalogs or magazine articles show the backs.

Regards,

Steve Price

Posted by Filiberto Boncompagni

on 08-26-2002 08:08 AM:

Hi Steve,

It depends on how the engsi is rolled up.

The ones

in the above pictures seem rolled UNDER the front.

I mean, for the pile one:

it seems the lower part was rolled under the upper one with the pile facing

outward.

The same for the felt: what we see is the front face, not the

back.

In any way, one side should be more sun-faded!

Perhaps, as Kenneth

wrote, they were used only in special

occasions.

Regards,

Filiberto

Posted by Steve Price on

08-26-2002 10:24 AM:

Hi Filiberto,

You're right. I hadn't noticed that. In any case,

if they were used regularly, there ought to be a faded horizontal band in the

place that was exposed.

Regards,

Steve Price

Posted

by Robert Anderson on 08-28-2002 01:13 PM:

It’s difficult for me to see from the pictures, but nothing in them

looks like a typical engsi-format rug. The last photo clearly shows a felt (or

a rug with a felt design) and the next to last photo shows what may actually be

a pile rug, attached to the outside of the tent with ropes and slung up and

over the top of the doorway. However, it looks wider than the doorway to me, so

maybe John’s idea that engsis should fit within the doorway, or perhaps be

a bit narrower isn’t valid.

As a person with a scientific bent, I

can appreciate any attempts to analyze engsis and other rugs using available

data. However, trying to do this with data obtained from books and other

second-hand sources is, in and of itself, risky. For example, how accurately

were the measurements made? Could there have been transcription errors in the

proof or in printing? How about pieces that are fragmented or reduced in length

at either end due to wear, which may include some of the oldest and most

interesting engsis? With this caution aside, I would like to make a suggestion.

Rather than presenting the averages of the length to width ratio (or similar

data) from engsis assigned to the different tribes, it might be more

illustrative to plot these data together on graph paper, for example, length on

the vertical axis vs. width on the horizontal axis. (Pinner and Frances in fact

did such an analysis of Turkoman tent bags. See ‘Tent bags and simple

statistics’, Turkoman Studies I). Then, any obvious clustering would

become apparent, which might otherwise be “blurred” by averaging. For

example, it might turn out that a subset of Tekke engsis lie outside of the

main Tekke group and much closer to the Salors. Another possibility is that

old-appearing engsis might tend to cluster together. This might occur, for

example, if engsis evolved from a common ancestral type. One problem here is

that there is not much agreement when it comes to estimating the age of rugs,

although characteristics like wool quality, dye usage and colors, and even

aesthetic judgments might have some usefulness. Also, how far back must we go

to a prototype, if in fact one ever existed? Two hundred years? A thousand

years?

What can be argued with a fair amount of certainty is that most

surviving engsis date from the commercial period, after around 1880 when the

Russian military and traders already occupied the region. As an aside, it is

unfortunate that more of these early visitors were not professional

ethnographers or anthropologists by today’s standards, which probably led

to the loss of much valuable information. In any event, the resulting social

unrest and commercial pressures were undoubtedly important factors for change,

perhaps causing engsis to rapidly evolve from whatever function(s) they once

had, finally into decorative throw rugs for the Western market. Therefore, we

should probably eliminate obviously late-appearing engsis (certainly ones with

synthetic dyes or eclectic designs, etc.) from our analyses, including many

Tekke, Yomut, Ersari, and even Saryk examples. So, now we are left primarily

with engsis from the Salor (a tribe that declined as a result of military

defeat before the commercial period), the Arabatchi (a small tribe that may not

have felt much commercial pressure), the Chodor (to a lesser extent), and a few

isolated tribal groups, a VERY small database of potentially

“authentic” engsis with which to work. Even the Salor may have led a

settled or semi-nomadic existence for a long time prior to their defeat, and

arguably engsis made by settled groups might have served a different function

than those made by nomads.

So what WERE engsis originally used for? The

most common proposal is that they were tent door rugs. However, several

arguments have already been made against this idea, which can be summarized as

follows: 1) the lack of expected weathering and fading on many examples thought

to be old; 2) the existence of few really convincing pictures of engsis in use

– most pictures show felts, or possibly pile rugs of indeterminate design

and size; 3) just as most engsis are bigger than the average prayer rug, most

seem to be too small for door rug use, whether or not they were hung inside or

outside the yurt entrance; 4) the use of an accessory germach to increase the

length is possible, but germachs seem to be much rarer than engsis with only

Tekke and very rare Arabatchi examples known, and 5) as opposed to thick, heavy

felts, most engsis would serve as poor barriers to the cold and wind. Some

believe that engsis were used only for certain festive occasions, such as

weddings, and that most of the time they were stored away with other dowry

goods. I sort of like this idea. Many believe experts that the majority of the

engsis surviving today are commercial products resulting from Western demand,

or that they were made as part of the prescribed dowry long after they ceased

having any utilitarian function. These ideas also seem plausible. Speculation

by some that engsis were used in a totem-like fashion (i.e., to denote clan or

social status) or that they were used in religious (e.g., shamanistic) rituals

are intriguing but cannot be supported with any evidence.

So where to

go from here? It is unlikely that the engsi format arose in isolation. So one

tack might be to look for it and associated design elements in old rugs (and

art forms) from other cultures and tribal groups, both inside and outside of

Western Turkestan. As was proposed in a post from another thread in this Salon,

compartmented rugs might be a starting point, specifically, compartment rugs

from Turkey; also, the garden carpets from Iran, and a possible analogue to the

four-square hatchli format seen in an old rug from East Turkestan (see

Schurmann, Central Asian Rugs, plate 90). Even rugs not organized into

compartments could be looked at for their shared design motifs and similar

structural features. Although the original meanings and significance of the

motifs and design elements used in Turkoman engsis and other rugs may never be

known, the Turkoman women appear to have had names for many of them (see

Tzareva, Rugs and carpets from Central Asia). Perhaps not surprisingly, these

names appear to be have been based upon the motifs’ resemblance to common

animate and inanimate objects found in everyday life. Religion with its

associated mystical and spiritual aspects undoubtedly played an important role

in Turkoman life, however, reality was comparatively harsh and the main

preoccupation would have been with obtaining the corporeal necessities. Thus,

the ‘kejebe’ (wedding litter on the camel) motif seen on some

Turkoman engsis (also the more explicit depiction of the wedding caravan on the

elem of Arabatchi engsis) may express hope for material wealth, a good marriage

and many children. The ‘kush’ (bird) motif perhaps symbolized birds

of pray and therefore success in the hunt (but see also, Neergaard,

‘Turkmen tent band figures used as design elements on carpets and

bags’, Oriental Carpet and Textile Studies, Volume 5(1), where it is

proposed that similar design forms are intended to represent ‘Toyon

Kogor’, “the lord of the birds and ruler of earth and sky”).

Other ornaments may have been used to “ward off the evil eye”,

ensuring health and prosperity. Whether we ever know the purpose for which

these rugs were made or the meanings of their designs, they will remain for me

a source of great fascination.

Robert Anderson

Posted by

Marla Mallett on 08-28-2002 11:13 PM:

Hung How?

Hi Folks,

I’m curious to know what evidence anyone has

found in the way of damage at the upper corners of their ensis…or what

evidence of any attached hanging apparatus has been found… Just imagine

the stress on any weaving hung from only a couple of points and then repeatedly

jerked around.

Marla

Posted by R._John_Howe on 08-29-2002

05:48 AM:

Correct Attribution

Dear folks -

I need to correct one indication by Mr. Anderson in

the immediately preceding post.

The notion that width of engsis might be

important was not my idea but rather one that occurred to Peter Andrews as he

considered the Ersari lady's indication that in her experience (she is likely

in her 50s) engsis were placed on the inside of the tent door.

Mr.

Andrews as some of us know, is probably the world's foremost scholar on such

tents having published in 1997 a very scholarly two volumes entitled: "Nomad

Tent Types in the Middle East."

Peter has promised to look to see if the

"scores" of Yomut tent door widths he recorded in the 1970s in the field are

locate-able. But it was his suggestion that most Turkmen tent doors are likely

120 cm or narrower.

Tomorrow I will give you a long quote from these two

volumes in which he discusses the "door flap" for a typical Yomut trellis

tent.

Regards,

R. John Howe

Posted by Steve Price on

08-29-2002 05:52 AM:

Torn Corners

Hi Marla,

I've seen a number of ensis with the upper corners

torn, I assume from the stress of being hung from them. Same for some juvals

and torbas.

Regards,

Steve Price

Posted by Filiberto

Boncompagni on 08-29-2002 06:40 AM:

Hi Marla,

Right.

Jourdan’s plates 57 and 58 show two

Tekke ensis with "hanging apparatuses" - the first one looks positively

original.

Also another Tekke "Door Hanging ensi, 133x181cm" from the catalog

of 1993 Genoa Exhibition "Carpets of Central Asian Nomads, has "At the corners,

small woven and pile rectangles folded to form a point with 55 cm long plaited

warps". The exhibition was organized by Elena Tsareva and showed almost the

same pieces of Dudin’s exhibition on ORR web site.

I can post the scan,

if you want.

Robert, congratulations for your comprehensive

posting!

Regards,

Filiberto

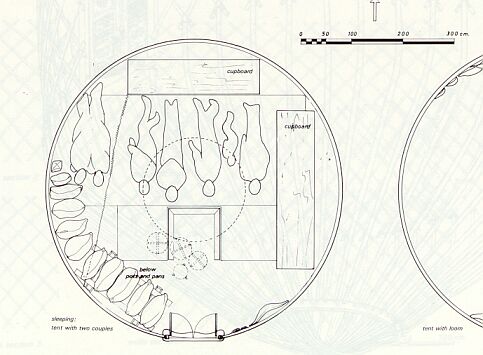

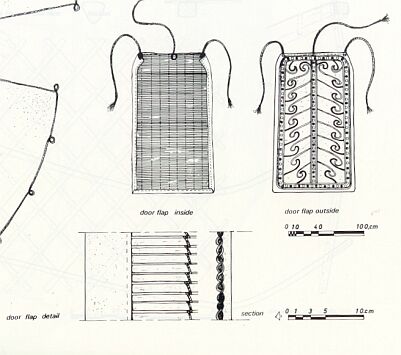

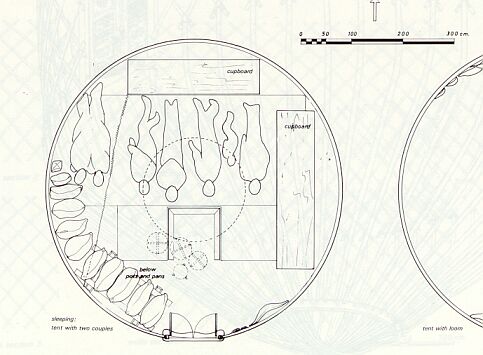

Posted by R. John Howe on

08-29-2002 12:13 PM:

Andrews Quote

Quote from Peter Andrews’ Volumes

Dear folks

–

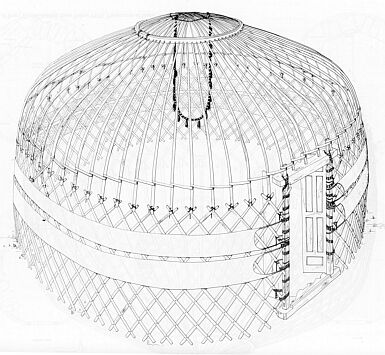

Here, below, is the long quote I promised you from Peter Andrews

volumes on “Nomad Tents in the Middle East.” This quote if from Part

I, Framed Tents, Volume I, page 67. It is headed “Tellis tent: Turkmen of

Iran: Yomut and Goklen.”

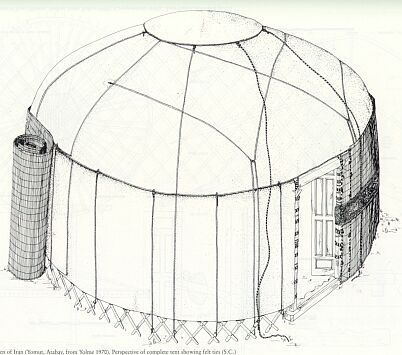

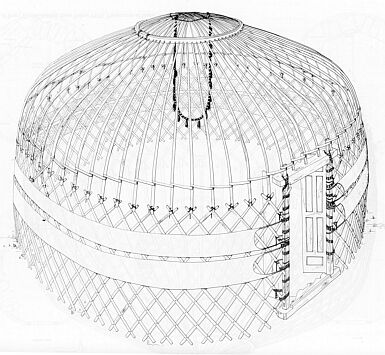

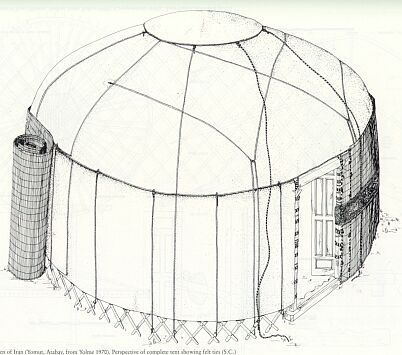

But first, for context, here are two of

the beautiful drawings of the sample Yomut trellis tent that Andrews provides

in Volume II. These drawings are to scale based on Andrew measurements. The

first two are by Susan Calverley. The third is by Andrews’ wife, Mugul,

who is also a rug scholar, part Turkman by heritage, and who accompanied him in

the field.

This first drawing is of the “Tent frame with

cordage.”

The second drawing is labeled

“Perspective of complete tent showing felt ties.”

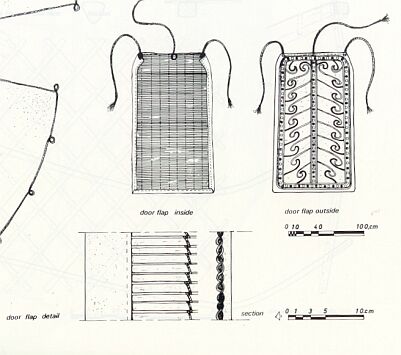

This is the text section headed “Door

flap:”

“…informants claimed that until 1920s the usual

door was a felt flap rather than the wooden door leaves usual nowadays. The

flap was still seen occasionally in 1970-74. The outer felt face is backed by a

mat of canes held horizontally and bound with vertical goat hair lines: this

allows the flap to be rolled up, still with the felt face outward, in such a

way that it will remain in place at the lintel, held by friction and its own

weight, when the doorway is open. It is made 110-120 cm wide to overlap the

doorposts and the front edges of the wall felts on either side, and 185-230 cm

long. The canes are 1m. long, and usually split in half before being bound, all

facing the same way, with 8 goat-hair lines spun S of 2 or 3Z passed around

each in turn at 10-13 cm intervals. They are then laid cut side downwards on

the felt, and the edges of the felt turned over their ends along the long sides

and at the bottom before being sewn down, forming an edge 3-7 cm wide. The top

part of the flap reaching from the level of the lintel upwards is tapered so

that it can be inserted easily under the edge of the front roof felts: it

varies in width at the end from 55-88 cm and in length from 18-66 cm. Ties are

provided at each of the top corners, and sometimes at the top centre. Where the

tapering upper tongue is long, a pair of ties may also be provided at the top

of the rectangular part: these can then be attached to the the top of the door

posts horns, about 10 cm above the lintel. These may be of black and while

plaits. Another set of ties is provided lower down for securing the flap at

night. The felt face is usually decorated with scrolled branching patterns of

colored wool laid in while fulling. This is the only instance in which the felt

tents themselves are coloured. The former importance of the door flap is still

indicated in the way in which the top corners of the cane screen are invariably

cut back on either side of the doorway to allow its insertion. The unique Yomut

name of the flap, “tarp yapar,” indicates the sound with which it

closes “with a clap,” or its speed, “in a wink.” Among the

Goklen it is called the “is ensi.”

In the example, the flap is

110 cm wide at the bottom, narrowing slightly to 106 cm at the lintel and then

more sharply over 18 cm to 88 cm at the top; the full length is 185 cm. There

are eight goat hair binding lines on the canework, both no leather strips, and

the felt edge is folded over for 3 cm only. There are three ties at the top

end, 65-75 cm long, in triple plaits of goat hair yarn, plied S of three

Z.”

Here are the drawings of the “door flap” from Volume

II.

Now, of course, this is all about a felt door

flap, but it gives a concrete picture of the logic that guided its size and

shape. I also provide this passage just to give you an example of the

meticulous description that Peter Andrews provides in these two

volumes.

One thing to be noticed about this door flap is that it is much

more a “length twice the width” shape than are most

“engis,” which at about 4 feet wide by 5 feet long are more nearly

square.

Regards,

R. John Howe

Posted by Yon Bard on

08-29-2002 01:46 PM:

Marla, I have a Tekke ensi with hanging ropes attached to the top

corners.

Regards, Yon

Posted by Robert Anderson on

08-29-2002 04:41 PM:

Thanks for the illustrations John. Then the door flap is a

cane-reinforced felt about 6 to 7.5 feet long and 4 feet wide so as to overlap

the doorposts? Sounds like a fairly sturdy arrangement, well insulated against

the cold and strong enough to withstand the wind. Most engsis are smaller than

this. So, unless tent doors were also smaller in times past, it would appear

that the engsi was never intended to be a functional door cover.

Robert

Anderson

Posted by Marvin Amstey on 08-29-2002 05:15 PM:

My Ersari engsi has the same corner ropes as seen here. But I believe

Marla's point that the continued wear and stress would pull them off. This

particular piece was probably not used. Interestingly, I had a Yomud main

carpet with the same braided ropes in each corner that I guessed were used for

pulling the rug over some goods and tying it down on a camel, elephant or

pickup truck.

Best regards

Posted by

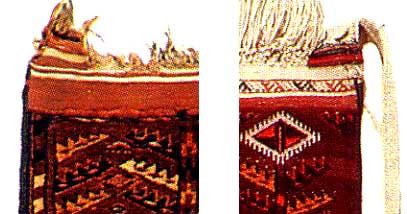

Patrick Weiler on 08-30-2002 09:57 AM:

Tie One On

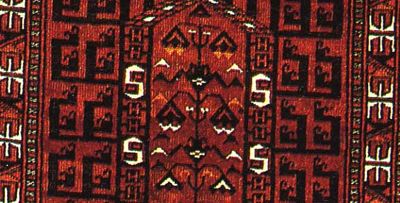

Here is another Turkmen trapping with tie ropes. (I do not remember the

source of this photo)

This one has them at what are usually called "closure

marks", the small, blue "V" shapes just below where the ropes are attached.

I do not recall seeing many of these bags with

"stretch-marks" or wear at the points assiciated with these rope attachment

points, but it may be that the entire top several rows of the bags were cut off

when they were prepared for sale, so any distress to these areas would have

been removed.

It may well also be that the engsi and many bags like this

one were not "used up", but kept as dowry keepsakes. Another idea regarding

engsi's is the likelihood that they were used inside the tent to separate an

area - possibly that of newlyweds from the rest of the tent. (the so-called

"door to Paradise"?

)

)

This would have minimized the wear one would associate with use as a tent

door.

Patrick Weiler

Posted by Yon Bard on 08-30-2002 10:56

AM:

Patrick, very interesting! This is the first confirmation I have ever

seen that the 'closure marks' were actually closure marks! This example,

however, does not appear to be analogous to the hanging ropes that appear at

the top corners of many asmalyks, torbas, and ensis. Btw, looking again at some

of my ensis, I noticed damage to the upper corners in some of them that I

hadn't paid any attention to before. There is little doubt that many ensis were

designed to be hung from their top corners and not tucked into door flaps as

suggested by Andrews. Anyway, the wide variation in ensi sizes suggests that

they were not as a rule meant to fit exactly into a confined

frame.

Regards, Yon

Posted by Chuck Wagner on 08-30-2002

07:27 PM:

A quick note

Greetings all,

Several months ago, during the Tent Pole Cover

salon, we got onto the topic of ensis, and I'd like to repost a couple of the

text blocks here because we agreed to wait until this salon came along before

continuing. We got to the ensi part by digressing away from a discussion on

Turkoman weddings.

--Block 1-:

In Afghanistan and Pakistan,

"ensis" are called "purdahs". Purdah (pardah) is the term used to describe the

generally Islamic phenomena of separating women from the world of the men. Some

refer to it as lifelong prison and slavery. The men, on the other hand, do not.

Regardless, I propose the reason that we have no photos of ensis being

used as tent/oy doors is because they weren't used as tent/oy doors. I think

that they were used as doors for internal dividers within the tents/oys that

separated the womens space (or private adult space) from other areas within the

tent/oy. They may well be the bridal curtain, which could explain the very

special, and entirely different appearance, that ensis have compared to other

Turkoman weavings.

I think this because of 1) the liguistic connection,

2) because the dimensions of ensis and purdahs are consistent with the larger

Kirghiz reed screen dividers, and 3) because the looped hanging straps (that

I've seen in photos) are just right for hanging on a line strung across the

interior of a stick frame oy.

--End Block 1--

Now, a couple of

the photos in this salon do look like they captured pile weavings used as door

flaps, so my comment about "no photos" is no longer reasonable. I will say that

none of the images are DEFINITIVE with regard to the classic ensi designs we

see, but one in particular is quite close.

Steve continued to bait us

regarding ensis in the Tent Pole Cover salon, so I added this next block

later:

--Block 2 --

OK Steve. I'll add a little something to

the things-to-consider heap, but mainly to get it on the record because I can't

be assured of having the book or a working computer later on. We'll discuss the

picture later, when John is ready.

I have laid hands on a book entitled

"A Journey to the Source of the River Oxus", by Capt. John Wood, Indian Navy

(Reprint: Oxford University Press, Karachi, 1976). Capt. Wood took a 3000 mile

excursion up the Indus to the upper reaches of the Pamirs in 1836. No

illustrations but a couple of nice maps. His attention to detail is remarkable.

He visited a Kirghiz encampment, and the following are some excerpts

from his text (he wasn't one for small paragraphs):

"We now asked

permission to rest awhile in one of their kirgahs, and were immediately led up

to one of the best in the encampment. Its outside covering was formed of coarse

dun-coloured felts, held down by two broad white belts about five feet above

the ground. To these the dome or roof was secured by diagonal bands, while the

felts which formed the walls were strengthened by other bands, which descended

in a zig-zag direction between those first mentioned and the ground. Close to

the door lay a bag filled with ice-the water of the family. On drawing aside

the felt which screened the entrance, the air of tidiness and comfort that met

our eyes was a most agreeable surprise. In the middle of the floor, upon a

light iron tripod, stood a huge Russian cauldron, beneath which glowed a

cheerful fire, which a ruddy-cheeked, spruce damsel kept feeding with fuel, and

occasionally throwing a lump of ice into her cookery."

----text---

"The kirgah had a diameter of fourteen feet, a height of eight, and was

well lighted by a circular hole above the fireplace. Its frame-work was of the

willow-tree, but between it and the felt covering, neat mats, made of reeds,

the size of wheat-straw, and knitted over with coloured worsted, were inserted.

The sides of the tent, lined with variegated mats of this description, not only

looked tasteful, but imparted a snug and warm appearance to the interior.

Corresponding to the outside belts were two within of a finer description, and

adorned with needle-work. From these were suspended various articles

appertaining to the tent and to the field, besides those of ornament and the

sampler. Saddles, bridles, rings, thimbles, and beads, all had here their

appropriate places. One side of the kirgah had the family's spare clothes and

bedding. In another, a home-made carpet hung from the roof, making a recess in

which the females dressed, and where the matron kept her culinary stores and

kitchen apparatus. The opposite segment was allotted to the young lambs of the

flock. A string crossed the tent to which about fifty nooses, twenty-five of a

side, were attached, to each of which a lamb was fastened."

--- End of

quotes ---

Lots of information in there, and I'm wondering if the

carpet mentioned might have been an engsi .

--End Block 2

--

I'll add a comment at this point: It seems to me that most of the

ensis in existence today are actually in pretty good condition, and I think

this adds credibility to the notion that many ensis were used as interior

dividers. Wouldn't a piece used as an exterior flap show significant evidence

of exposure to the elements, and have substantial distortion at fold and hinge

points ?

Regardez: How many felt door covers survive today ? (Captain

Wood is careful to note that the door flap is felt but the interior wall is a

home-made carpet.)

Further, I doubt that it's just a coincidence that

the Afghanis and Pakistanis refer to these pieces as purdahs. There must be a

cultural connection there.

I'll leave it there for now; I'm travelling

and it may be a couple days before I can get back to respond to additional

comments.

Regards, Chuck

(p.s. If this salon is still going when

I get back to my home computer, I'll post a couple scans of illustrations from

another old book)

Posted by Kenneth Thompson on 08-30-2002 11:05

PM:

Pile or Felt Doorflap in Photo

Dear All,

I have been looking more closely at the photograph that

seems to show a pile ensi. Since this would be the first time I had ever seen a

pile door-rug photographed in situ, I downloaded the complete TIFF uncompressed

file and played a bit with the contrast. Upon further examination, I am now not

at all certain that it is not felt after all. The way that the motifs pucker

out in relief as if quilted and the general fall of the material looks like

felt after all. Also, the design itself does not look like any pile ensi design

I have seen, but then I could easily have missed something.

Am I the

only one who sees this as felt or do any of you have doubts that it may not be

pile?

Best Regards to all,

Ken

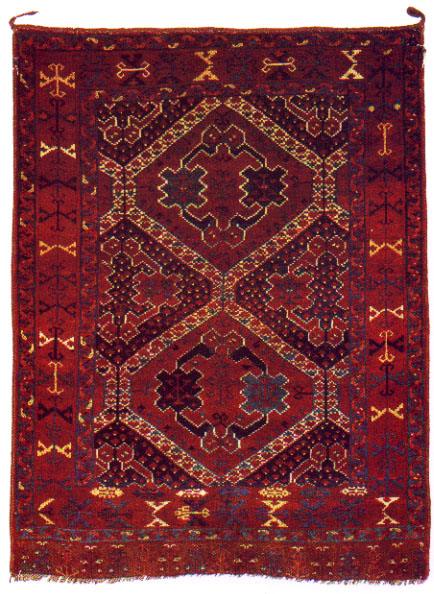

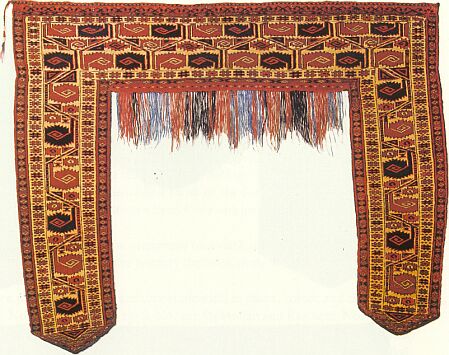

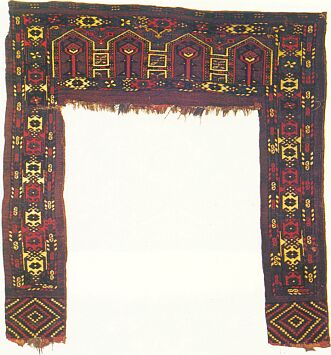

Posted by R. John Howe

on 08-31-2002 08:54 AM:

One More Reason for "Not Inside" Use

Dear folks –

(I wrote this post before I saw Chuck Wagner's

that is a couple above this one, so I'm not responding to what he says. But to

follow on his suggestion that the engsi might in fact have been used as an

internal curtain, I will post separately a couple of detailed internal layouts

that Peter Andrews provides.)

There is one more reason for thinking that

engsis, during the years when they were in more general use, albeit likely for

special occasions only, were NOT placed, as my Turkmen lady friend thought, on

the inside of the tent door.

It is, as many of us know, because there

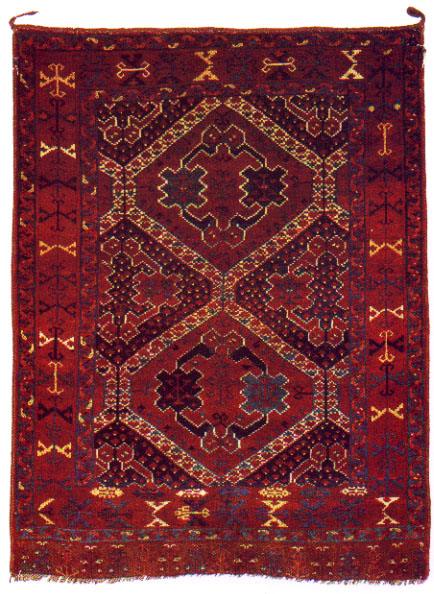

was another Turkmen format for that precise purpose. This type of Turkmen

weaving is most frequently described in the rug literature as a

“kapunuk,” or door surround. (In the last quote in the introductory

salon essay, Peter Andrews used the term “qapiliq” to refer to this

inside door surround; I specifically questioned him about its meaning and he

verified that it denotes a door surround. I did not ask him if this is a

Yomut-specific term, but given the literature usage of “kapunuk” that

seems likely.)

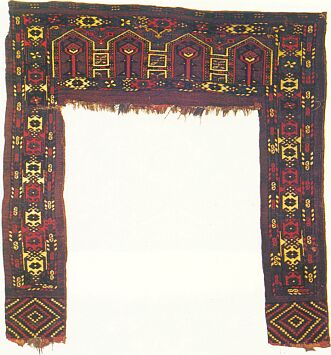

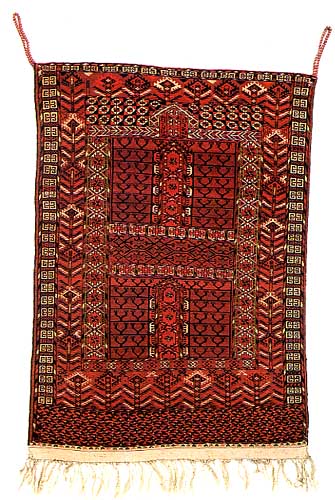

Here is a Tekke version:

Loges gives its measurements as: 0.88 (0.23) X 1.08 (0.61)

m.

Here is a Chodor version that may be older:

Loges’ measurements are: 1.13 (0.34) X 1.10 (0.21)

m.

This format, it may not put too fine a point on things to specify, is

contrasted with the similarly shaped “khalyk” which is perhaps

one-half to two-thirds as wide and is thought to have been a decoration either

for the breast of the wedding camel or for the (top front?) of bride’s

litter. (There are Yomud "khalyks" that are wider and composed of several such

sections that puzzle the authorities.)

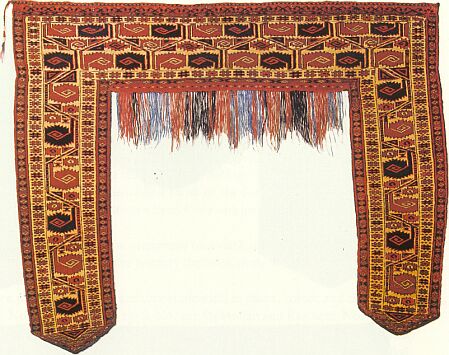

Here are two Tekke khalyks also

from Loges:

He gives the measurements of the top one as:

0.43 (0.27) X 0.73 m. His measurements for the second one are: 0.4 (0.34) X

0.71 m.

It seems unlikely a kapunuk and an engsi would have been used

together on the inside of the tent door.

Regards,

R. John

Howe

Posted by Robert Alimi on 08-31-2002 09:58 AM:

Hi Ken,

I don't see anything about the design that indicates

felt. But if it _is_ felt, the level of design detail that's observable even in

these photos would make this one heck of an interesting piece of felt work!

Here's an attempt at enhancement using Photoshop's contrast and sharpen

controls:

The drape on the left side is strange, but the right side

of the piece doesn't look like at all "poochy" where it is folded under itself.

It'd be most helpful to see a color image. The Prokudin-Gorskii collection

consists of glass plate negatives and contact prints. The LOC has been able to

make some great color prints from the glass plate negatives, but this image

appears to have been scanned from a contact print so it's most likely not

available in the original glass plate negative.

Regards,

-Bob

Posted by Steve Price on 08-31-2002 10:14 AM:

Hi people,

The conventional wisdom, which is right most of the

time, is that felt ensis were used routinely and pile ones were for special

occasions. The fact that we don't have many really old felt ones around is

easily understandable from the fact that they got hard, daily use and looked

awful by the time they were old. Besides, few collectors cared about central

Asian felt until pretty recently, so not many would have been preserved in

collections.

But what did the Turkmen do with pile ensis between

special occasions? Well, using them as internal dividers in the yurt makes

sense, and they were sensible people. So, perhaps the answer to the question,

"Was the ensi a divider inside the yurt or a door flap?" is, "Yes, it was a

divider inside the tent and yes, it was also a door flap

sometimes."

Chuck says he's never seen old ensis in poor condition.

Those don't find their way into books very often, but one dealer at the

Indianapolis ACOR had a Tekke ensi that looked very old to me, and it

was in tatters. I've seen a few others like that, too.

Regards,

Steve Price

Posted by Kenneth Thompson on

08-31-2002 01:42 PM:

Felt or pile Ensi

Dear Bob,

Your Photoshop enhancement does push the surface back

toward the pile option, though I know that there are very fine felts as well.

Thank you very much for keeping the question alive, since this is a crucial

area of doubt.

It would also help if a language scholar could further

identify the origin of the word itself. John's lady who says it comes from

"yengse" or "back of the head/nape," could be right. But I have doubts. In

Turkic languages "en" or "eng" is the way to make a superlative.

"Iyi"="good"."en iyi"=the best. And "en iyisi"="the best of the all" "En" also

is the word for "width" and in Kirghiz "ensiz" means "narrow." It is probably

none of these and may come from a Mongolian source("Egsi" is the Mongol word

for "felt") or even Chinese, about which I don't have a clue. There are

probably a lot of other possibilities.

I mention this abstruse issue

because almost all of the other yurt related words have a functional meaning,

such as kapilik(or kapinik), eshik tish, tegerich etc. It would be odd if ensi,

however spelled or pronounced, did not.

Sorry for such a long

post,

Best regards, Ken

Posted by R. John Howe on 09-01-2002

06:09 AM:

Ken -

I want to correct any impression I may have made that Ms.

Meredova, the Ersari lady, to whom I have referred, suggested that "engsi"

comes from "yengse." She emphatically did not. She merely indicated when I said

I had "my head down" working, that "yengse" means back of the head. She did

then go on to say that most "engsis" in her experience were hung on the inside

of the tent door. But these were separate points. As I have tried to make clear

in a separate thread, Peter Andrews also felt that these two words were not

related but indicated that one must be cautious since neither of them

apparently has an etymology. This was the reason he did some additional

checking.

Just want to make sure that any potential confusion I may have

introduced with my "story" does not persist.

Regards,

R. John

Howe

Posted by Christoph Huber on 09-01-2002 02:16 PM:

Dear all

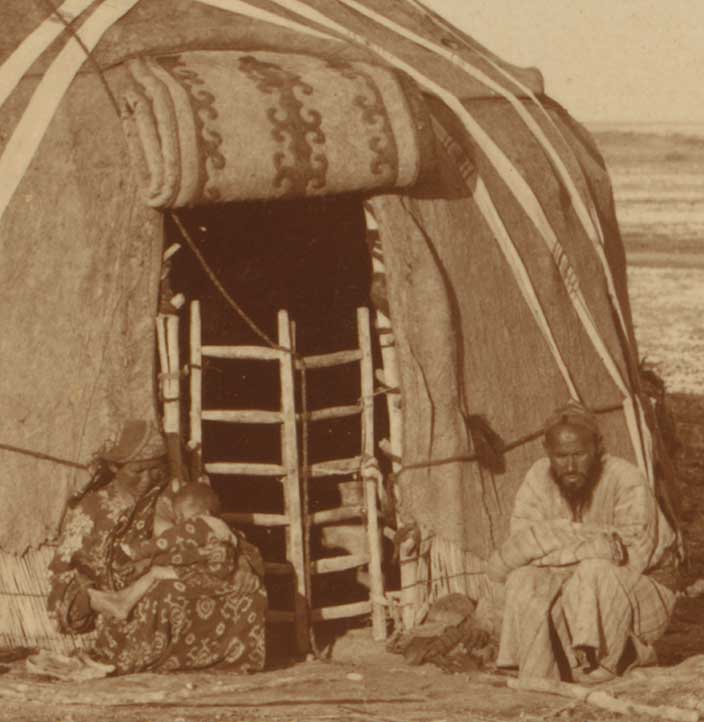

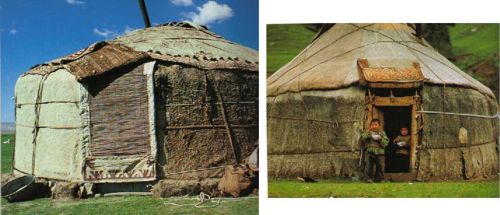

I would like to add some more pictures of yurts. The

engsis aren’t neither knotted nor Turkmen but I think they are quite

interesting and give additional illustration of Peter Andrews descriptions of

the construction of yurt flaps.

The door of the Kirghiz yurt to the

left consists of two “layers”

- a reed screen with enforced edge

and a decorative felt at the bottom and

- an ornamented felt which is folded

back. (Turkmen peoples, I suppose, on special occasions would have replaced

this felt by a pile knotted engsi.)

The on the Kazakh yurt to right the

similarly decorated reed screen is folded twice (and not rolled as on the

pictures above). The second “layer” (felt or knotted rug) isn’t

attached.

A Karakalpak reed door as well decorated with a panel (most

probably knotted on the open shed) is shown in “Music for the eyes” .

Elena Tsareva, not referring to a specific people, writes that door hangings

were made of knotted textiles, felts, reed screens or a combination of all of

these. They were used according to weather conditions.

It’s

probably a bit off the theme here, but the panels decorating the bottom of the

reed screens look very much like “germech”, don’t

they?

One could argue that the germech-like elems which can be seen on

many engsis have their origin in the panels sewn on the reed screens. If the

engsi would have been folded as seen on the right picture only this part would

have been exposed to the sun and because it’s of a different coloration a

bit of fading wouldn’t do much damage to the aesthetic of the whole

weaving.

And apart from that, if folded this way one can see the whole

(germech-)panel but doesn’t have the impression of seeing only a part of

the engsi’s ornamentation.

Interesting seems to me also this

North-Caucasian Nogaian wedding-yurt .

I

believe to have seen a picture of a similar Central Asian “flag/door”

but I didn’t find it anymore...

I also wanted to post in this context

a picture of one these odd-shaped Chodor rugs usually called either prayer rug

or engsi. Maybe someone could help with a reference?

I guess that

pardahs would be a different thing: Azadi shows a striped Yomut rug which he

describes as a pardah. This rug copies flatweave designs and I suppose that

most of the textiles used to divide the yurt were just flatweaves.

A friend

of mine had such a striped Yomut rug which had ropes still attached and so

could support the assumption of its use as a pardah.

On the other hand,

there are also huge main-carpets with ropes, possibly used to secure the carpet

if rolled up?

Marvin, I love your Ersari engsi but according to the

Rietberg Museum, Zurich it’s a Chodor chuval...

Best regards and many thanks for the interesting

salon,

Christoph

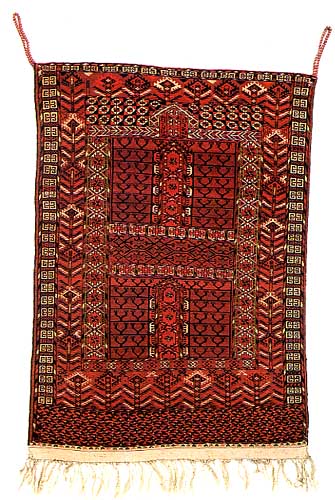

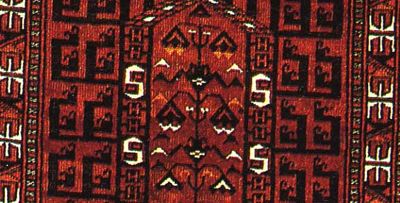

Posted by Daniel_Deschuyteneer on 09-01-2002

03:21 PM:

Dear all,

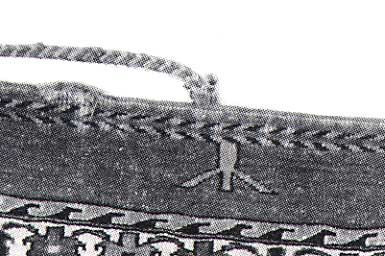

This is somewhat out of topic but as Patrick showed one

example in an earlier thread that got Yon Bard interest I add this picture for

information, showing another Yomut chuval with ropes still atached at the

“closure marks”

Source is :Teppische aus Mittelasien und Kasachstan

– Exhibition catalog of the Russische Ethnographic Museum Leningrad

Ermitage plate 80

Thanks,

Daniel

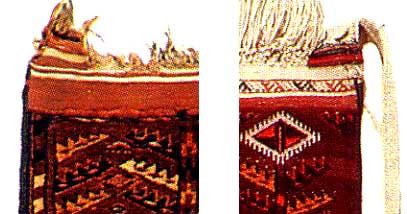

Posted by

Daniel_Deschuyteneer on 09-01-2002 05:14 PM:

Dear all,

I add here some pictures coming all from Teppische aus

Mittelasien und Kasachstan – Exhibition catalog of the Russische

Ethnographic Museum Leningrad Ermitage

References of the plates are

included in the name of the jipeg file.

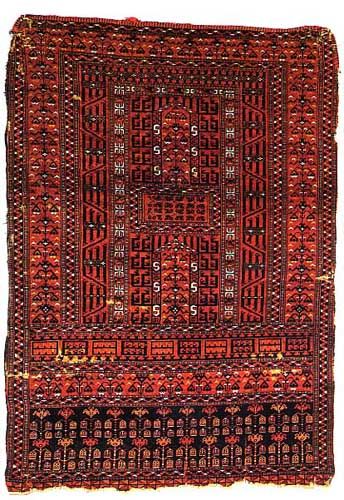

First let me show this picture

from a Khirgiz eshyk tysch. Long ropes attached at each upper corner are still

present.

And here is a close up

Here is now a Saryk engsi showing both worn upper corners,

a braided fastening band fixed along the top border and the sideway oriented

“candelabra” discussed in another thread.

close up of the two color braided band

Close up of the sideway oriented

“candelabra”

Now let us look at a Tekke engsi showing two colors

braided ropes at each upper corner

and here a close up

Here is another Tekke rug with another kind of

fastening system. At the base of the ropes there is a (piled?) triangular

stripped reinforcement

You can better see it in this close up

and here are two close up assembled in one picture of the

corners of two Tekke RUGS (not engsi) showing the same construction as on the

upper engsi. This construction is may be typical of Tekke pieces. At least I

didn’t find any other piece that wasn’t Tekke showing this

structure.

Is the presence of fastening

systems a way to sort pieces which were woven for local

use?

Thanks,

Daniel

Posted by Christoph Huber on

09-01-2002 05:51 PM:

Dear Daniel

The first of the "Tekke rugs" is according to E.

Tzareva an engsi and I would agree with her on this. But it looks very Yomut to

me, not Tekke.

The following rugs are good examples of

Yomut-weavings.

The main-carpet I mentioned in my previous post was a Yomut

as well. There isn’t any pile on these prolonged kilim-stripes which form

the basis of the ropes (at least in the case of the carpet I’ve seen in

the wool).

Best regards,

Christoph

Posted by

Deschuyteneer daniel on 09-02-2002 08:15 AM:

Dear Huber,

You are right the first Tekke "RUG" I show, which is

with the striped weft faced reinforcement at

the base of the rope is an engsi and not a rug and it is presented in the book

as an engsi. I apologize for this mistake.

Best,

Daniel

Posted by R. John_Howe on 09-02-2002 02:11 PM:

Dear folks –

This is a response to Chuck Wagner’s

suggestion that since the Afghan term for “engsi” is

“purdah” and since this latter term is also sometimes used to refer

to the area in which female members of a family (e.g., in the case of a

“harem”) are separated from others in an Islamic home, perhaps one

possible use for the “engsi” might be for such “purdah”

screening in the nomadic tent. Chuck quoted one traveler and visitor to a nomad

tent who reported seeing a carpet used as a kind of privacy curtain.

I

think this is an imaginative suggestion and it seems true that many textiles

that we tend to see as used in singular ways in fact had multiple uses. So I am

not here discounting the possibility that what Chuck suggests may have been in

some cases correct.

Peter Andrews work, which I have been

“mining” liberally in this salon, makes a different

suggestion.

First, in the Yomut community Peter studied first hand, a

newly married couple did not usually live together. After the marriage was

consummated on the wedding night, the bride typically returned to her

family’s home and the couple did not live together for perhaps the first

two or three years of their marriage. About the fourth year, the bride joined

the groom, but again usually the couple does not yet have a tent of their own,

so they live for a time with the groom’s parents. During the initial

period after the bride comes to the groom’s parents’ tent, it is held

to be important that the bride avoid contact with her father-in-law and in fact

most of the more important members of her husband’s family. To provide for

this there is a sequestered area of the tent in which the bride sits. And there

is a cloth used to provide this private space. Here is part of Andrews’

discussion of this aspect:

‘…If a new bride is living with the

bridegroom’s parents, she can sit with her face uncovered behind a

curtain, “tuti,’ of cotton with coloured tags hung on a black and

white rope, “tuti yupi,” stretched across the heads in the same

northwest corner or northern part of the tent where the couple also

sleep…”

Andrews provides a drawing of this sleeping

arrangement that also shows how this rope would be arranged with the

“tuti,” hanging over it.

Andrews cites William Irons on the “tuti,” and

in George O’Bannon’s little volume based on what was then Marvin

Amstey’s collection, Irons says, “…The “tuti” was

usually gaily decorated brightly colored strips of cloth, but was not a fine

piece of weaving. It was placed on a rope and arranged so that it could be

pulled back, opening up the area behind it one occasion…”

So

while Chuck Wagner’s suggestion might sometimes have been the case, it

seems that in the Yomut communities that Andrews and Irons studied first hand,

there was a different textile, the “tuti” used to create the

“purdah-like” space in the tent and it seems not to have been a woven

carpet.

Regards,

R. John Howe

Posted by David R.E.

Hunt on 09-03-2002 01:29 AM:

Purdah

Dear R. J.Howe and all- Not that I am a linguist, but it is my

understanding that the term Purdah is Persian and not Turkic, and that It does

refer to a room divider/dividing rug suspended by straps- And to complicate it

even more I have seen some of these large rugs with robust hanging straps being

sold as Purdah-yet with that exploded Mina Khani pattern common to the Ersari

and Beshir, and a vigorous rendering at that! Market influences?

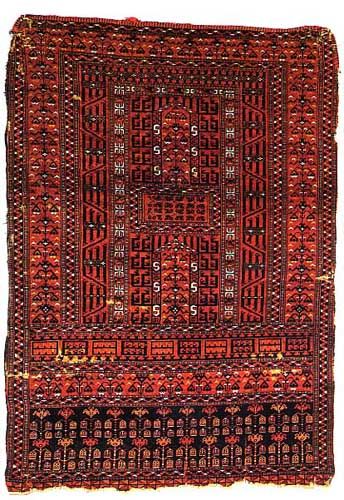

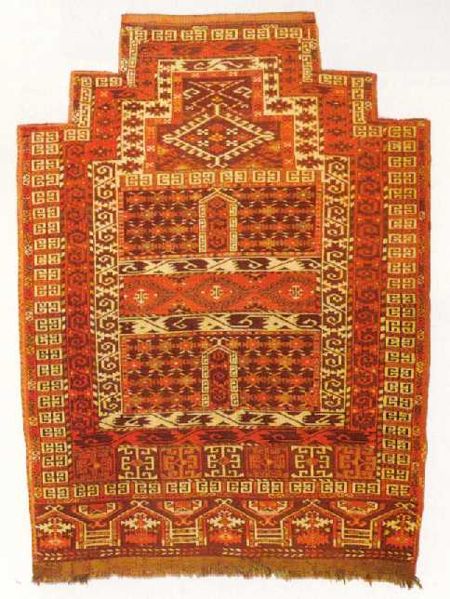

Posted by Christoph Huber on 09-03-2002 06:59 PM:

Dear all

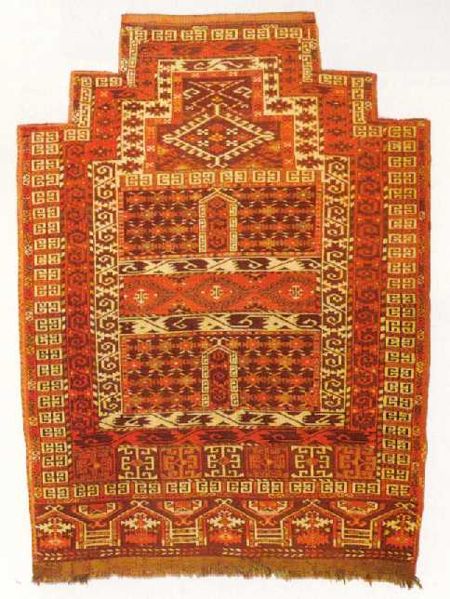

I found the “odd” engsi I’ve mentioned in

my previous post:

“Chodor, Ensi (?)”

Orientteppiche aus Österreichischem Besitz, Vienna, 1986, p.

117

I wonder whether the tapered form only corresponds to the form of

many reed screens used for yurt doors or (less likely?) whether it represents a

knotted version of a “flag/door” as seen in the picture of the

Nogaian wedding-yurt.

Best regards,

Christoph

Posted by

R. John Howe on 09-20-2002 07:14 AM:

Width: One More Time

Dear folks -

Just when you might think we've finished with this

thread, I have found a reason for one more post here about door

width.

Yesterday, while visiting the Textile Museum library, I also

peeked in at their upstairs gallery where they've been responding to frequent

calls to make Meyers' collection more accessible by putting up pieces from it

under different themes.

The current theme is the use of silk in rugs

and textiles and one piece they have is an older Turkman door surround with

sumptious silk decoration in places. This piece is in good condition and seems

likely to have been used only on a special occasion basis.

One is not

allowed to touch exhibited items at the TM but I could get my hands close

enough to determine that the opening in this piece is just about three of the

lengths of my hand wide. My hand is almost precisely 20 cm long and so this

opening is only about 60 cm wide. People would definitely have brushed this

piece at the sides as they went and out (I am a sizable person but my shoulders

are about 65 cm wide), but the external width of it is less than

120cm.

Regards,

R. John Howe

Posted by Kenneth

Thompson on 09-20-2002 12:12 PM:

Purdah in Turkish usage

Dear David,

In Turkish, "perde" is the standard word for a

curtain. Turkish has for a long time been heavily laced with Persian words.

Following Ataturks reform of the alphabet, there has been an effort to

substitute "pure" Turkic words--words from Central Asian languages--for words

of Arabic, Persian, and even English derivation. The effort has partially

succeeded, but you often have to learn two or three words for the same thing,

since they can appear at random in publications or even on road signs (eg,

"tamir" and "onarim" both indicate a road under

repair.)

John,

Peter Andrews published a picture of a tuti

somewhere, but I can't find it. It looks like a bedsheet with rows of

good-luck/apotropaic tassels all over it.

Regard to all,

Ken

Posted by Sue Zimerman on 09-20-2002 07:54 PM:

Dear John,

Did to silk in the TM Turkman door surround come from

Europe, the Caspian area, or China? Sue

Posted by R. John Howe on

09-20-2002 09:50 PM:

Sue -

Well, of course, there's no way of knowing in a particular

instance but there was silk production in Central Asia in some of the areas in

which the Turkmen with the engsis and door surrounds lived. Bukara was not only

a major marketing outlet for Turkmen weavings, it was one city in which the

suzani and ikats were made. And the Ferghana valley had a silk production even

larger than Bukara's and even exported silk to East Turkestan. Suzani designs

are embroidery in silk and were sometimes done on a silk ground. Ikats designs

are made with silk warps. So the fact that there is silk decoration on some

Turkman pieces (and it was sometimes lavishly used in pile areas) is likely the

result of local silk production, not imported silk.

Regards,

R.

John Howe

Posted by Sue Zimerman on 09-21-2002 12:14 AM:

Dear John,

I would like to know where, in fact, the silk came

from. Silk was also being produced in Europe through the 18th century. Georgia

and even Greece were producing silk well into the 19th century. It could have

been brought to the Turkmen with dye from Germany or otherwise, too. Someone

should know this, shouldn't they?

We have a lot of things here in the US

produced locally that we buy from China. If we want to know influences we

should know what influences they were exposed to. If there are facts available

I think they should take precedence over conjecture. Don't you? Sue

Posted by R. John Howe on 09-21-2002 06:37 AM:

Sue -

I agree that factual data is always preferrable to

conjecture, but it's going to be difficult to determine where silk in a given

Turkmen piece came from at least until they develop far more fully the

techiques that permit one to tell such things from the dyes and from the

wools.

And the Turkman lived close to, if not directly on, what is

famously called "The Silk Road," and likely for a reason. So imported silk is

always a possibility.

Despite this, the fact that it is also known that

there was vigorous local silk production in the areas where the Turkmen lived

(cotton too) to the extent, in the case of the Ferghana valley, that they

actually exported some in the direction of China, (the treatment silk

production in Bukhara in the catalog by Andy Hale and Kate Fitz Gibbon on the

Goldman ikat collection is extensive) seems to me to provide a pretty sound

basis for thinking that the silk in Turkmen carpets is mostly of local origin.

Turkomaniacs have examined all kinds of arcane features of their beloved rugs

since the 1970s at least and I've not heard someone raise this question

before.

And I'd don't know how you'd determine its answer for a given

Turkmen piece.

Regards,

R. John Howe

Posted by Sue

Zimerman on 09-21-2002 12:53 PM:

Dear John,

I am not asking out of idle curiosity. I am doing a

lot of research to discover the answer to a question raised by my last

research. A German connection would defiantly answer this question once my new

research is applied to it. If there is no German connection resolution will be

more difficult, but the new information will be illuminating nonetheless. I am

in the process of cleaning it up for posting.

Can you, or can anybody

else, clarify the approximate time frame of old, middle and late engsis? Unless

I have missed it, I cannot find this information in this salon.

I have

read the shamanism thread. There is one thing I want to clarify now. Please

don't think that my suggestion that the Hatchli pattern could represent the two

phases of the Milky Way's appearance at migration times is exclusionary. I

believe Jourdan's suggestion is valid. I also think the Hatchli pattern is a

door and a garden, too. What I am suggesting is that there is another level of

concrete meaning woven into it which allows for it to be more than a two

dimensional representation. I think that the design encompasses a third axis

which allows it to be viewed as more than a schematic.

A "Milky Way's eye

view" requires of the viewer to mentally pull the upper cross bar into the

heavens and push the lower cross bar to the opposite side of the earth. Once

this is accomplished the viewer can see the "sky map" with the vastness

analogous to that which is portrayed in western art by means of three point

perspective. In other words I think that the illusion of space is not, as we

have been taught in the West, a Renaissance invention, but a western

translation. Clear? Sue

Posted by Steve Price on 09-21-2002 01:20

PM:

Hi Sue,

I can respond to the part of your post that asks about

the ages of ensis. In my opinion, the oldest ones we have were probably made

around 1800, give or take 25 years. Most antique ensis were made in the last

quarter of the 19th century. Those made later aren't antiques, and, in any

case, a very large number were made for sale to the west after 1875 or

so.

Does everyone agree that the oldest ones are late 18th/early 19

century? No. There is a school of thought, to which I do not subscribe, that

there are Turkmen textiles around that date back to the 15th century. Those who

believe that, probably also believe that a significant number of ensis predate

the 18th century. The people in that group, by and large, have old Turkmen

textiles for sale.

Regards,

Steve Price

Posted by

Sue Zimerman on 09-21-2002 02:20 PM:

Dear Steve,

Thanks! That helps. Sue

Posted by Yon

Bard on 09-21-2002 03:11 PM:

Steve, you made the following remark:

"Does everyone agree that

the oldest ones are late 18th/early 19 century? No. There is a school of

thought, to which I do not subscribe, that there are Turkmen textiles around

that date back to the 15th century. Those who believe that, probably also

believe that a significant number of ensis predate the 18th century. The people

in that group, by and large, have old Turkmen textiles for sale."

If

this isn't ad-hominem, I don't knoe what is. Ii is OK to contest the carbon 14

datings on scientific grounds, but not by imputing base motives to their

promulgators.

Sue, when you theorize about the meaning of the ensi

patterns, do you think the individual weaver had these things in mind, or just

that that's how the pattern was originally developed? I am sure it is fun to

"see" things and speculate about their meaning and origin, but please be honest

and tell us what you really think is the likelihood that your particular

interpretation is the correct one.

Regards, Yon

Posted by

Steve Price on 09-21-2002 05:20 PM:

Hi Yon,

As you know, I am skeptical about the reliability of C-14

dating as applied to oriental rugs made within the past 400 years or so. I

believe the statements in my post are true, and I was very careful NOT to say

that the people who believe differently than me are frauds who are

misrepresenting the stuff they have for sale. If anyone cares, I think some are

and some aren't, but I can't read minds any more than anyone else can and my

opinions of their motives are irrelevant.

It is a fact that most of the

people who profess that there are Turkmen pieces around that are more than 300

years old are those who are trying to sell those pieces. It is also a fact that

almost nobody can be totally objective about a piece in which he has a

financial interest, particularly a large financial interest, particularly when

he makes a living from it. So, their opinions on this matter, whether sincere

or bogus, contain a source of bias. That bias may well be subconscious, but the

question of whether there are 400 or 500 year old Turkmen pieces has

consequences for them. It is inconsequential to me, and to most of

us.

This, of course, is exactly why we don't permit discussion of items

that are on the market. Objectivity, difficult to attain for almost anything,

is even more difficult by orders of magnitude when there are financial

interests involved.

This is ad hominem to the extent that it recognizes

that we are humans and that this is human nature. It was not an attack on

anyone's character, intelligence or motives.

Regards,

Steve

Price

Posted by Sue Zimerman on 09-21-2002 07:11 PM:

Dear Yon,

The weaver would have to know what the symbols mean.

She would have to know the "grammar", how to put the "words" into "sentences".

I don't think she would have to know deeper meanings than the concrete ones or

where they originally came from. She would have to know the story and how to

tell it.

The only reason I'm telling what I see is that the symbols seem to

be obsolete. If they were not I would have to consider who am I working for?

The code value for symbols is enormous. They can be used for evil. I want no

part of that sort of thing. I am too squeamish to look at the new rugs. I have

just checked them to make sure the ones I'm studying are not used anymore. More

than what you asked but important to say.

I am just following the

direction the Engsi is leading me, and offering my findings as I go. I wouldn't

do this if I wasn't convinced it was real, and could lead me to what I should

be looking into next. It has lead me to history, not my cup of tea at all, but

it is panning out.

It doesn't mean I'm right that I have probably spent

more time looking at this sliver than it took to weave, and probably more time

than anybody else on the planet has, but it does say something toward my belief

it has something to say. So, yes, I think that what I have said up to now about

it is correct -- not that what I have said is the whole picture.

I

haven't seen enough close ups to work out the planets yet but I have worked out

many other symbols. There are symbols which represent more than one thing, just

as there are words that do, which will take more time to know.

I think I

should be cut some slack. Engsis have been around a long time without being

deciphered. I only began this when this salon started.

Dear

Steve,

Since the subject has been raised, perhaps it is just my bias,

but those things called "smiles" add absolutely no clarity to what is meant in

a post and are offensive, ugly, and not funny. They hurt my eyes. Sue

Posted by Steve Price on 09-21-2002 07:43 PM:

Hi Sue,

The smilies are also known as "emoticons", which more

nearly expresses what they're about. They are widely used on web discussion

boards and even in e-mails to try to convey what is conveyed in face-to-face

conversation by body language, facial expression and tone of voice - the

unspoken messages sent by your emotions. None of those things is possible in a

purely written venue, at least, not without getting terribly verbose. Many

venues that don't use emoticons use other commonly understood shorthands for

the same purpose; stuff like LOL (laughing out loud), ROFL (rolling on the

floor laughing), and making sideways faces out of the colon, hyphen, and

various forms of brackets in different combinations.

Obviously, they add

to the enjoyment some people get from using these boards, and there are some

who use them in ways that I think are creative and inoffensive (I'm thinking of

Vincent Keers here). On the other hand, we don't think ugly or offensive are

good things to be, and I guess I have to take you at your word when you say

that they hurt your eyes, although I find it hard to understand that part.

I'd like to get other peoples' feelings on those things before taking

any action. Would you open a new thread on our Miscellaneous Topics section

soliciting opinions on this?

Thanks,

Steve Price

Posted by Filiberto Boncompagni on 09-22-2002 02:31 AM:

Hi Sue,

In other words, smilies/emoticons are nothing else than

modern SYMBOLS. And their good side is that they cannot be used for

evil.

Regards,

Filiberto

Posted by Sue Zimerman on

09-22-2002 12:07 PM:

Dear Filiberto,

If you are saying that modern symbols are simple

and shallow, I disagree. Sue

Posted by Steve Price on 09-22-2002

12:33 PM:

Hi Sue,

Filiberto didn't say anything about the depth or

simplicity of modern symbols, only that smilies are part of that group. Nor did

he say that this subcategory of modern symbols is simple and shallow. Indeed,

some people react to them much more strongly than I would expect if these were

shallow symbols.

Regards,

Steve Price

Posted by Sue

Zimerman on 09-22-2002 12:43 PM:

Dear Steve,

I've go to step out of this Chinese trick box and

back to work on my evidence that you won't buy. Time is a tyrant. Ta Ta,

Sue

Posted by Chuck Wagner on 09-22-2002 04:38 PM:

I see, said the blind man as he picked up his hammer, and

saw...

Hi All,

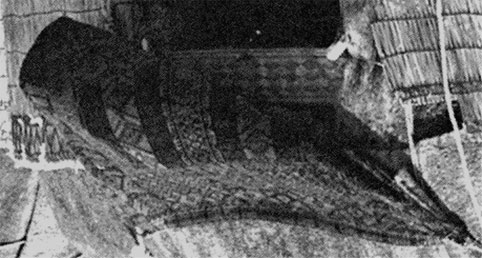

First, go back to Bob Alimi's post in this thread of

8/31/02 2:08, which shows

an enhanced view of a pile weaving used as a door

flap on a yurt.

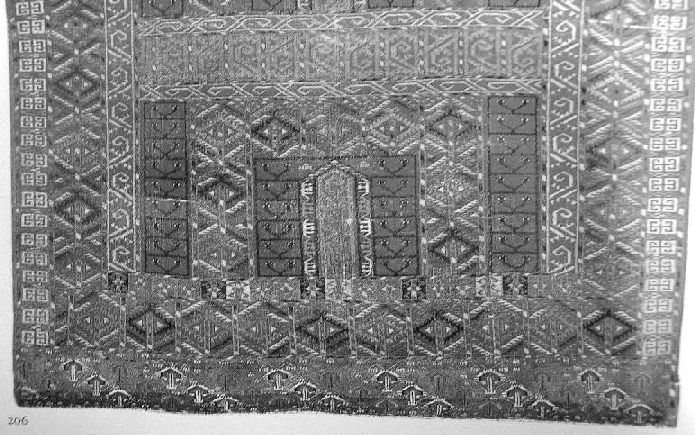

Then, look the new edition of Eiland & Eiland's

Oriental Carpets:

Page 232, plate 206: A 19th century Tekke

ensi

It MIGHT even be the same rug...

Regards,

Chuck

__________________

Chuck Wagner

Posted by Yon Bard on 09-22-2002 05:07 PM:

Chuck, great similarity, but the bottom-most panel (topmost in the yurt

picture) are different.

Thanks for putting in an append that actually

deals with rugs.

Regards, Yon

Posted by Robert Alimi on

09-22-2002 06:19 PM:

For the sake of convenience, here's another view, this one flipped 180

degrees.

Also, several of Pinner's quotes regarding

engsis have been mentioned during the salon, but I don't recall his "Atlantic

Collections" quote having been posted before. For what it's worth, here it is

(from pg 173):

"The ensi is a door hanging with the design displayed

outwards from the yurt. That its use was confined to the Turkmen wedding

ceremony and perhaps for other special occasions, is supported by the fact that

its colours rarely show the fading which would follow prolonged exposure to

sunlight."

I think he's got it right.

Regards,

-Bob

Posted by Sue Zimerman on 09-22-2002 08:22 PM:

Dear Yon,

Pardon me for taking the time to try to thoughtfully

answer the rug question you asked me. It won't happen again. Sue

Posted by Yon Bard on 09-22-2002 09:07 PM:

Sue, please forgive me. I am becoming cantankerous in my old

age.

Regards, Yon

Posted by Sue Zimerman on 09-23-2002 05:43

AM:

Dear Yon,

I understand, I forgive you.

Has anyone else

noticed that the 1885 yurt drawing in John's opening essay has curtains drawn

to the sides which could be pulled down, like the yurt's in the background, to

protect the engsi from sun damage? Sue