The Salon du Tapis d'Orient is a moderated discussion group in the manner of the 19th century salon devoted to oriental rugs and textiles and all aspects of their appreciation. Please include your full name and e-mail address in your posting.

by Michael Wendorf

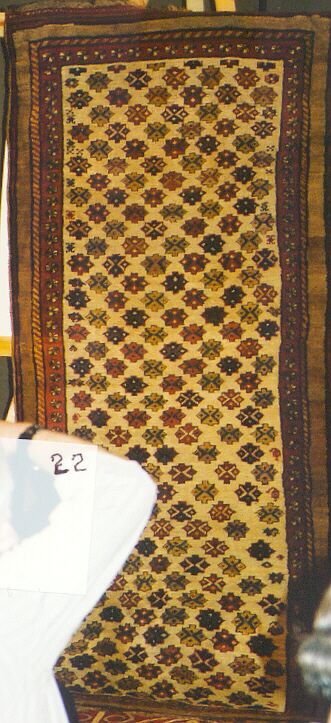

The rug above is an example of a rug where the stepped polygons are expressed more positively. Knotted pile rugs with stepped polygons are among the most common traditional Kurdish rugs with innumerable variations in color and color combinations. Another example is this rug.

Other examples of knotted pile rugs with origins in Kurdish

flatweave traditions include this unusual ivory ground example:

The field design of this rug is one I have seen in the borders of a

small handful of other rugs. It also probably has its origins in warp

substitution.

There are also specific motifs that I consider to be

traditionally Kurdish, these almost invariably come from flatweaves. One

example is the so-called shikak motif seen below.

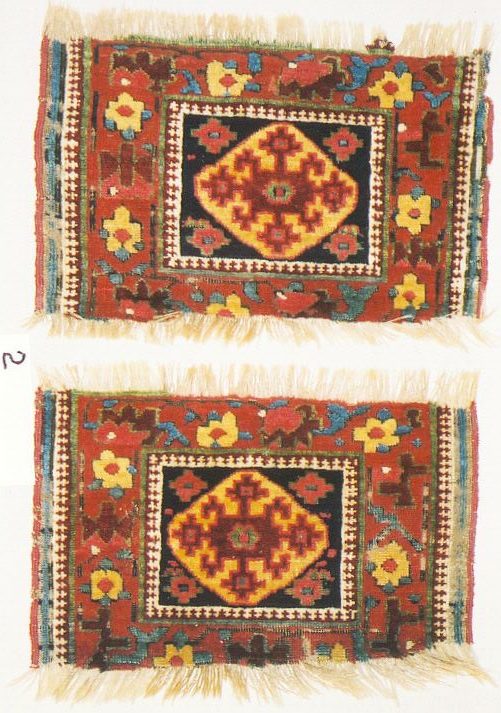

This same motif is seen in a distinctive group of Kurdish rugs as part of an all over lattice design. Jon Terry advertised one of these in the Hali ACOR preview issue. Here are two others, one belongs to me and the other to Roger Hilpp.

In later rugs this motif becomes mixed with other miscellaneous motifs and sometimes becomes halved causing it to look and often be identified as a cloudband or cloud collar. I believe its origins are in flatweaves, perhaps slit tapestry.

We do not know where these Shikak pieces

originated. What we do know is that they wove in western Iran, west of Lake

Urmia and north of Sauj Bulaq in the past. My own observation is that these

pieces were probably woven by several groups in several places.

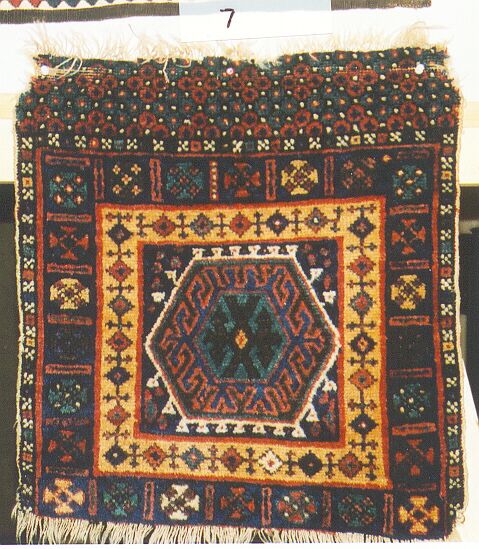

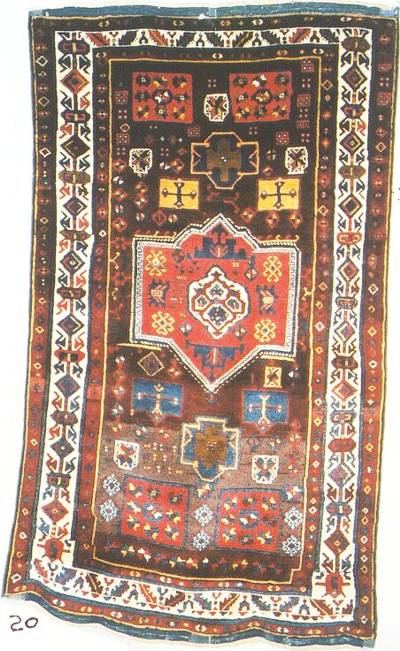

Another motif that we can think of as Kurdish is this medallion that is most

commonly found in knotted pile rugs.

For all that I have said about Kurds and flatweaves, we know very little about the weaving of more conventional soumaks by Kurdish weavers. It is almost as if Kurds never moved beyond weftless soumaks. That said, there are a few soumaks that have been tentatively identified as Kurdish. This piece, also illustrated in Wertime's book "Sumak" as plate 138, is one of them. Spaced wrapping warps may be an indicator of Kurdish origin.

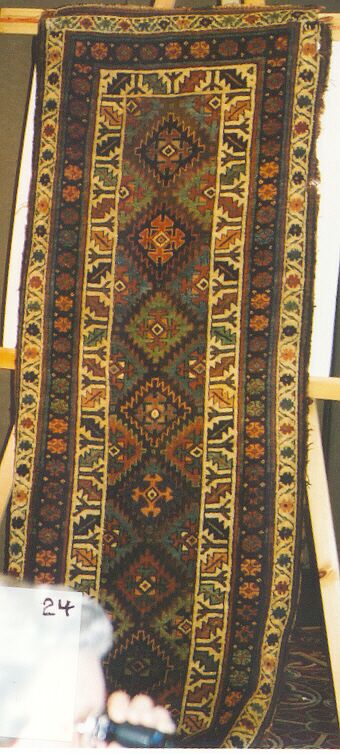

Another design that I have seen worked in soumak that was probably Kurdish in origin is the motif found in this long rug.

Although popular among Kurdish weavers, this motif must be considered pan-Persian, as it is found among many of the major tribal weaving groups.

One regularly confronts cochineal in Kurdish rugs from eastern Anatolia. It is not clear when this insect derived dye became available to Kurdish weavers in this area. Conventional wisdom is that this is not an old color, but Harald Bohmer has shown that it was available, at least in some areas, locally.

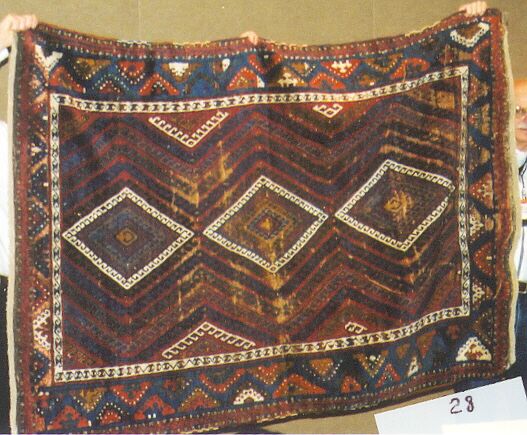

The rug above seems to me to be truly tribal. The design is one of

simple concentric diamonds that seems to have its origins in (what else?)

flatweaves. On the back tufts of dyed, but unspun, wool very similar to the

wool of the sleeping rug depicted earlier are added, perhaps as good luck or to

ward off the evil eye.

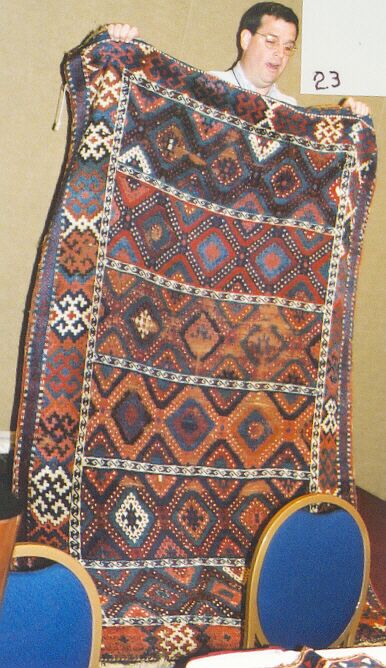

Another type of east Anatolian Kurdish rug is

the so-called Baklava types, which come as either all over patterns or in

compartments. Here we see a compartment rug.

Note the borders and the playful reciprocity expressed there. I think

these rugs originate around Gaziantep, although Eagleton seems to think

Malatya.

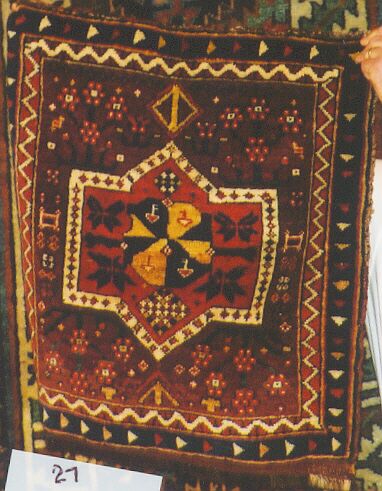

The second rug illustrated in this Salon is from around

Kagizman; it has blue wefts characteristic of this area. Here is the only bag

face that I know of with this medallion as a central design element. However

this piece has red wefts. Also, note the four shrub forms that are used in lieu

of geometric forms to create the 2 -1 - 2 design.

The medallion in this bag face and the second illustrated rug from around Kagizman are part of an interesting group of Kurdish weavings. The side borders on the Kagizman rug are distinctive. Note also how in the Kagizman the top diagonals of the medallion are jagged, almost as if a mountain peak is being drawn while the bottom one is a straight diagonal.

I have observed this jagged treatment of the upper diagonal in

several other rugs within this group. Other assymmetries abound throughout the

rug. A connection to Caucasian Karachovs seems obvious yet they are quite

different in coloration and feeling. Perhaps a connection to rugs in the

Holbein tradition accounts for both groups.

It seems to me that

thinking about this rug we observe Kurdish colors and wools but in other ways

it is quite different, especially in patterning. I think we see angular and

vertical elements in these medallion pieces that we

tend not to see in

Kurdish flatweaves because such patterning is natural in knotted pile. It is

not natural to flatweaves. This may explain the Kurdish synthesis that Klingner

has observed in knotted pile. In knotted pile, Kurdish weavers may have felt

more free to adapt and adopt a variety of to them foreign elements than they

did in more, to them, traditional flatweaves. What else explains this dichotomy

between traditional flatweaves and tendency toward synthesis when weaving

knotted pile rugs?

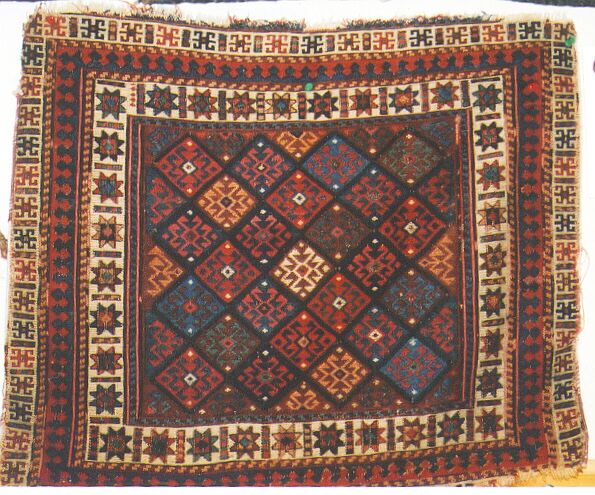

SO, WHERE ARE THE JAFS?

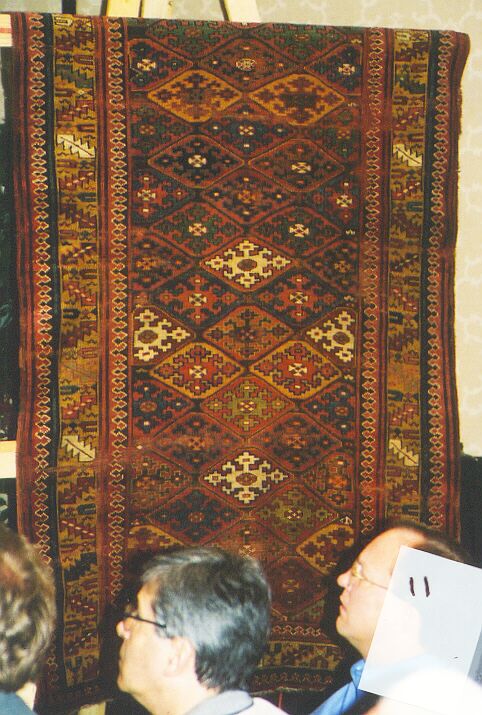

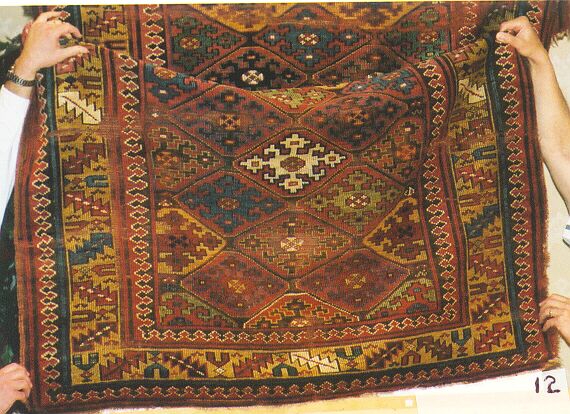

A similar issue arises when we consider Jaf Kurd bags. Every collector knows these knotted pile weavings with fields comprised of diamond forms containing diagonally drawn hooks.

As much as I enjoy Jaf Kurd weavings, I think their abundance has created a bit of a red herring. Jaf Kurd bags probably are a relatively late innovation among Kurdish weavers. I tend to think they arise out of a brocade tradition. The reason is that while the most natural hooked designs in knotted pile are angular, horizontal and vertical. By contrast, the most natural hooks in brocade are diagonal, formed by progressively offset knots. In Jaf bags, Kurdish weavers use offset knots to imitate the triangular looking hooks naturally occuring in brocades.

Finally, I leave you with a favorite among many favorites. This ivory ground long rug with radiating leaves came out of Alexandria, Virginia along with another rug with this same border. A border that I refer to as rosette and shrub. Initially, I did not know what to make of the border. Then I happened to run across the McMullan Kurdistan Garden carpet now at the Fogg. It had a very similar border. I then examined the borders on every formal Kurdistan garden carpet I could find photos of. I saw this border, usually on a blue ground with red rosettes and shrubs, frequently. I started asking other collectors about this border and identified three other examples. All have ivory fields with either this pattern or an all over three part floral motif.

Probably a village workshop produced these rugs throughout the 19th

century. This group was, until a group of 5 was exhibited in an exhibition

sponsored by the Near Eastern Art Research Center in 1999, undocumented.

Discoveries of rugs and groups of rugs such as this are still possible

when collecting Kurdish rugs. I hope you will be inspired to collect a few of

your own and to consider whether the place of Kurdish weavers needs to be

reexamined against the possibility that they are right in the middle of not

just the history of weaving, but the innovations and traditions that have kept

weaving vibrant and alive over the past 8000 years.

My thanks to John

Howe for photographing these rugs during an ACOR presentation. All the

mistakes, errors and omissions are mine, not his.

Michael

Wendorf