Posted by R. John Howe on 07-24-2002 09:02 PM:

Other Indicators of a "Deep Tradition?"

Hi Michael -

Thanks for a carefully set forth and

well-illustrated argument. Not everyone nowadays actually makes an

argument.

In other versions of this presentation I've have heard, you

referred to two other indicators that seem to be missing here.

I seem

to remember that the "frequent presence of goat hair" in later Kurdish rugs was

seen perhaps to be in part reflective of the fact that goats were domesticated

before sheep. The logic here would be that, as with particular weaving

techniques, the Kurds tended, perhaps more than others to continue to use the

materials they used earlier.

Secondly, you have sometimes mentioned,

with some emphasis, the fact that several shades of natural colored wools

appear in later Kurdish rugs, long after dyes have been available and again a

question of persistence of old practices was suggested.

Does the fact

that neither of these indicators was treated here suggest that you have revised

your view of them to some extent as potential indicators of a deep Kurdish

weaving tradition or did I misunderstand your treatment of them

originally?

Thanks again for a precisely constructed salon

essay.

Regards,

R. John Howe

Posted by Michael

Wendorf on 07-24-2002 10:24 PM:

other reasons

Hi John:

Thanks for supplying photographs.

I am not

certain what to do with the goat hair. I tend to look for it, especially in the

wefts, as an indicator of a tribal piece (as opposed to a village or more

commercial product).

I think the argument you articulate is one that is

difficult to support since it just seems so clear that at some point, possibly

quite an early point, wool became the fiber of choice. Ryder has written on the

subject of goat hair versus wool, it is hard to draw conclusions applicable to

the rugs we have had handed down to us. Simplifing greatly, early on goat hair

was a better choice than wool because wool was virtually unweaveable. As wool

became more like what we know it today, it replaced goat hair. That said, the

Siirt rug stands out as a type worth thinking about. This is a type were a

teasel is used to create a faux pile.

The second argument which involves

the use of undyed wools, the range of colors available to Kurdish weavers

naturally - from black to tawney to reddish brown to ivory - and the resulting

abrash (which I think might have become ingrained as a result of traditional

use of these undyed wools and the natural variations of these undyed wools) was

omitted from the ACOR presentation because the rug used to illustrate this

argument was in the concurrent exhibition and unavailable for use in my

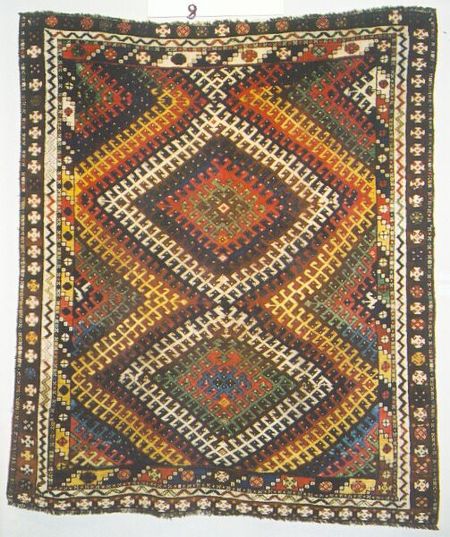

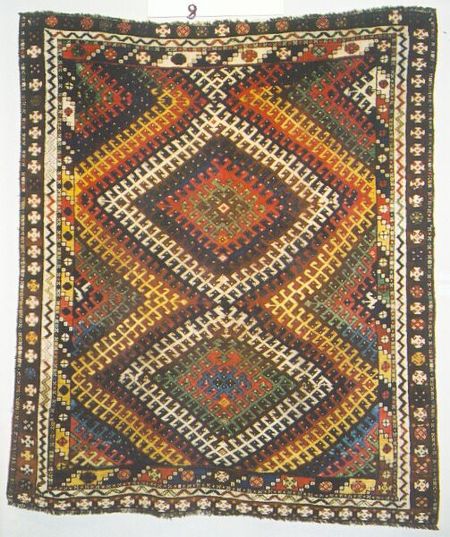

presentation. The rug I reference is the one with the two plus concentric

diamonds with hooks.

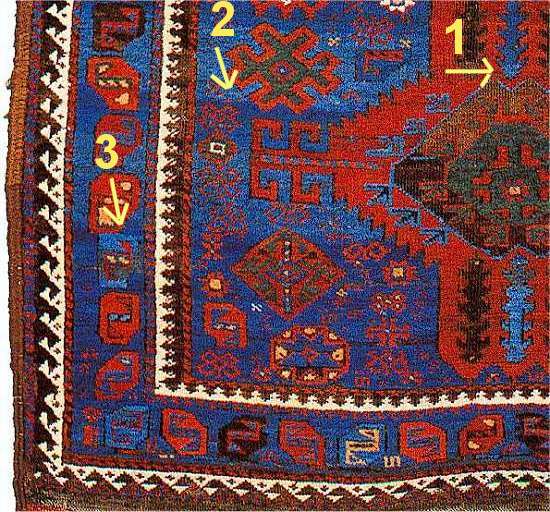

Editor Note: The image was inserted here after the

message was posted

In that rug all of the colors except the truest

red, yellow, green and blue are natural undyed wools. To bring it all full

circle, the red, yellow and blue dyed colors in that rug are all colors that

would have been available locally as early as 6000 B.C. according to other

research done in Anatolia. Of course, the green would likely have been an

overdye.

Thanks again for your assistance.

Best, Michael

Posted by Michael Wendorf on 08-07-2002 10:53 PM:

What about abrash?

Dear Readers:

Among the issues raised by John is the use of

undyed wools. In another context, John questioned me about my interpretation of

abrash and its possible role as an indicator of a tradition. As John then

pointed out, abrash is generally attributed to one of two circumstances. First,

it is described as a kind of mottling due to the fact that natural dyes "take"

differently to differentially to hand-spun wools which vary in thickness and

possibly even the degree in which they are spun. The result is that there are

subtle color variations within a single color in a single rug. Second, is the

instance of small dye lots with which it is presumed that traditional dyers

worked. This resulted in more marked color changes horizontally in rugs as

weaver came to the end of one lot in a given color and moved to another.

I have another interpretation of abrash and it arises from my

experience with the rug displayed above. From the first time I saw it, I

questioned the source of the colors that turned out to be undyed wools in the

rug including the pronounced abrash in the brownish/red border.

There

is very pronounced abrash throughout this border that clearly has nothing to do

with either (1) the way the non-existent dyes took to the wool or, (2) the size

of the non-existent dye lot. As I was thinking about this I happened to have

been reading about the domestication of sheep and early wool in Elizabeth

Barber's books. I was struck by the descriptions of the color or pigmentation

of this wool. Then I examined a number of photos taken by Ed Kashi in Kurdistan

of Kurdish sheep, paricularly of flocks along the Iraqi border area. Again, I

was struck with the range of colors and the near dominance of brown and tawny

colors - the same colors in the border of this rug. As I thought about this

more and sought out other rugs it occurred to me that these were colors that

would have been available to Kurdish weavers even before dyes were widely

available. With a limited color palette, how does one create color change? By

creating what we call abrash. Similarly, if undyed wool is what is available

and it naturally is abrashed does not this abrashed look become ingrained over

time as a kind of aesthetic?

If abrash is the result of a deeply

ingrained aesthetic resulting from the long use of undyed wools that have

naturally occuring color variation, then its use in rugs with dyed wools is

intentional and reflects the traditional use of undyed wools. In my opinion,

this explains the use of abrash in certain Kurdish rugs (including village rugs

with persianate designs) that otherwise have absolutely brilliant color and

fabulous wool. My sense is that the use of abrash, sometimes even the

exaggerated use, in such rugs seems less likely to result from a small dye lot

or the way the dye took to the wool and more likely a conscious attempt to

create abrash because the weaver liked the look of abrash - a look she came to

like because this is a deeply ingrained aesthetic.

I would like to hear

what others have to think about this theory of abrash.

Thanks,

Michael

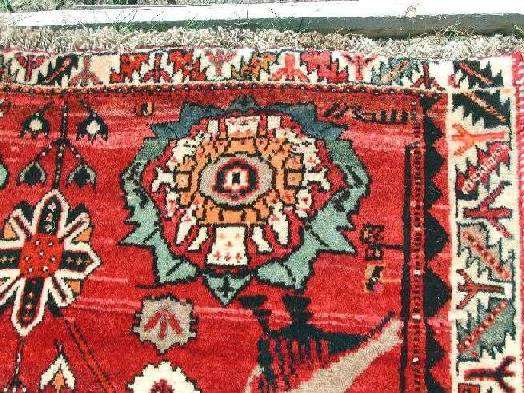

Posted by Bob Kent on 08-08-2002 02:12 PM:

out of the blue and into the black?

MW: This isn't abrash if abrash is a variation in one color, but some

Kurdish rugs seem to have surprising changes from one background color to

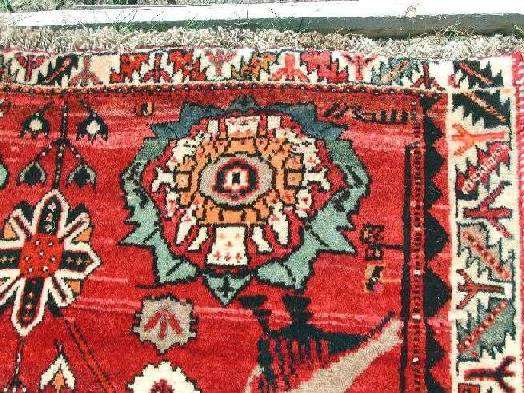

another. For example, the photos of my sauj bulaQ

rug

show that the field color changes from blue to black to brown. The background

color of the outermost border abruptly changes from red to yellow, and the

middle border's background changes from red to orange. I have another Kurdish

rug where the field color goes from blue to black. Of course such background

color changes may be as common in other rug types?

rug

show that the field color changes from blue to black to brown. The background

color of the outermost border abruptly changes from red to yellow, and the

middle border's background changes from red to orange. I have another Kurdish

rug where the field color goes from blue to black. Of course such background

color changes may be as common in other rug types?

Posted by Sophia

Gates on 08-08-2002 02:54 PM:

Color Variations and A State of the Heart

Bob et. al.,

First - whoa - Michael - what a rug! And same to you

Bob - that rug of yours is beyond awesome. The color variations both in the

background and within the "guls" are amazing and show a very imaginative mind

at work.

I think this kind of freedom with color is one of the keys to

understanding Kurdish weaving. There is a sense of play, real creativity, to

their rugs, regardless of the seemingly simple and repetitive shapes they

employ.

Indeed, I think of the "Kurdish heartland" as a state of mind

more than anything else. After all, they share their territory with a multitude

of other peoples. Yet their rugs, once one becomes attuned to them, are

distinctive.

Michael, I think your argument of using variations in wool

color deliberately makes absolute sense. Might I add: the variations in wool

color would also affect the COLORED wool. Painters use techniques like this,

creating visual effects by varying the color of the background, then glazing

over it with transparent colors. The final coloration would then depend

partially on the glaze color and partially on the color of the underlying

ground.

Best,

Sophia

Posted by R. John Howe on 08-09-2002

08:21 AM:

Dear folks -

The thing that caught my attention, when I first

heard Michael make his argument that abrash is likely the result of weaver

intentions to produce something similar to what they had seen when using undyed

wools, was what might be called the "relative plausibility" of this

thesis.

We don't usually have much information about what weavers

"intended" and we already had two alternative explanations of abrash that

seemed to explain both instances of it adequately and did not rely on weaver

intent.

It seemed to me that the traditional explanation had more

relative plausibility than did the thesis Michael was offering. I say despite

hearing Sophia's indication that painters do similar things.

I do know

of one instance of weavers intentionally inserting the more marked form of

abrash (that is the species traditionally attributed to small dye lots). In his

Turkmen Ersari project, Chris Walter told me that he had to school his Ersari

weavers at first in the degree of this species of abrash to use. He could dye

in large lots and so this sort of abrash had to be put in deliberately and he

asked them to do so. But they initially overindulged and made their intentional

abrashes too dramatic and extensive and actually made the rugs less attractive

sometimes.

I think Michael's suggestion is imaginative and I admire his

sharp eye in examining historical information that might suggest it, but for

me, the traditional explanations are still relatively the more plausible ones.

Regards,

R. John Howe

Posted by Filiberto Boncompagni on

08-09-2002 10:56 AM:

Deliberate abrash?

Yes, absolutely.

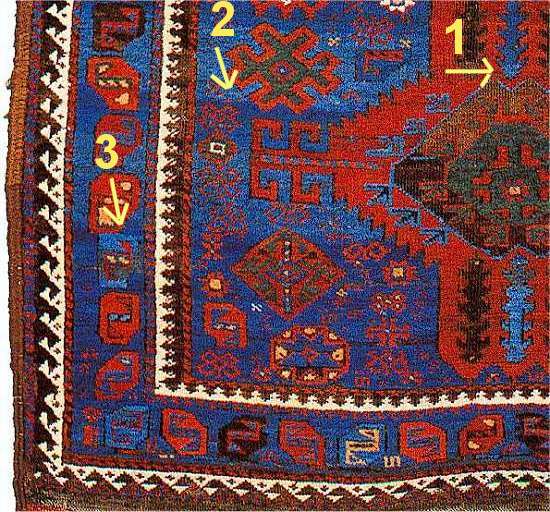

The Caucasian rug I showed

at the end of Salon 63 has a blue background, both for the field and the main

border. The blue is the same but inside the field is abrashed while inside the

border is not.

I apologize that this is not a Kurdish rug and the

picture is a bad quality enlargement of an old one - the rug is in storage now

and I don’t want take it out:

You

see? The darker blue extends to the # shaped decorations of the two minor

borders and arrives up to the selvedges but skips the main border and some

motifs inside the main field.

The only explanation I can offer is that it

was made on purpose.

I didn’t look around very much for other examples

but Kaffel’s plate 51, a Chichi prayer rug, seems to have also an abrashed

blue field and a non abrashed blue border.

Although I don’t think

that all the abrash was intentional, I agree with Michael that some was

probably "ingrained aesthetic".

And I DO like it.

Filiberto

Posted by Bob Kent on 08-09-2002 11:15 AM:

not abrash, but background color changes

I still wonder about background color changes, which might be similar to

- and beyond - use and appreciation of abrash. the first photo in the 'sauj

bulagh' thread shows the outer border jumping from orange to yellow, and the

third photo shows the field jumping from blue to black. maybe the weaver was

just running out of colors, but if I scan a lot of caucasian rugs in bennet's

book, I don't see many sharp background-color changes in borders or fields. I

don't see them in turkmen rugs either

Posted by Sophia Gates on 08-09-2002 11:35 AM:

Accident? Or design?

I'm a little surprised that some of you seem to feel that pure accident

is easier to believe in than deliberate aesthetic choices by a weaver!

I

am curious as to why this is. Do you not believe that these rugs were created

by artists, i.e., people capable of creativity, of making independent aesthetic

choices?

Or, do you think they maybe simply "happened"?

To me

it's so obvious - people make conscious & deliberate choices when they

work. For groups of people - women in certain areas where weaving is done -

their art might be the ONLY place where they are PERMITTED to make conscious

and deliberate choices.

I'd like to hear WHY those of you who find

accident and the ravages of time "less plausible" than creative

choice!

Best,

Sophia

PS - Bob, does this answer your question

about the backgrounds? They look like that, absent evidence of untoward

chemical changes to the dyes, because the weavers WANTED THEM TO LOOK LIKE

THAT.

S

Posted by R. John Howe on 08-09-2002 03:25 PM:

Hi Sophia -

I think you're speaking primarily to me since I made

the counter argument.

The reason I think that the "abrash as

intentional" thesis (I would not deny that a weaver might sometimes do it

intentionally) is less plausible than the two others I have heard, is that it

seems likely that neither of the latter could be avoided in traditional

circumstances.

I have not seen any instances of natural dyes applied to

hand-spun wool that does not result in a visible variation in color, a kind of

"mottling" effect.

And, if, as we think, traditional dyers dyed pretty

unavoidably in small lots, then the more dramatic species of abrash was also

unavoidable to them.

It is this unavoidability that seems attached to

these two theses that make them for me more plausible than the notion that most

abrash is deliberate.

Note that I can hold this position, as I have

suggested above, without denying that sometimes a weaver might insert abrash

deliberately.

The difficulty is that we are born 150 years too late to

know for sure.

I do not denigrate the weaver's skills or art but rather

am impressed with two seeming "necessities" as the more likely source of this

variation.

Regards,

R. John Howe

Posted by Michael

Wendorf on 08-09-2002 04:24 PM:

abrash

Dear Readers:

I do not think anyone is denigrating anyone's

skills or creativity as a weaver to challenge or question a theory or

conclusion. And none of us knows what a weaver intended, we can only reasonable

infer from a body of rugs, the information at hand. I do, however, think we

need to look at this body of rugs and related weavings when we discuss abrash

and not just rely on what we think we know about traditional dying or the

product/result of dying in the past. We know relatively little and what we do

know does not present a very clear picture.

In this vein, the abrash in

the rug with concentric diamonds is very pronounced in the areas with undyed

wools, especially the brownish red main border. This abrash looks to me like

what we call abrash in rugs with dyed knotted pile and I thought it was until I

had it tested. In the areas with dyed pile, there is no comparable abrash. In

fact, I would go so far as to say there is no discernable abrash except for

some areas of green.

John states above that he has not seen any

instances of natural dyes applied to hand-spun wools did not result in a

visible variation of coloring, a kind of "mottling effect" which I assume is

synonymous with "abrash" as used by John. If this is true, it is support for

conventional explanation # 1 - the way dyes "take" to hand - spun wool.

While what John states may have some truth to it, I do not think it is

accurate, at least as an explanation for abrash. If it were, every rug woven

using hand -spun wool and natural dyes would contain abrash. And not just every

rug, every color.

I also do not think explanation #2 - the small dye

lots explanation covers what we can observe in rugs or even the more dramatic

examples. There are too many rugs were it would appear the weaver had access to

whatever wools she wanted and still included abrash for effect. And it would

not explain how you can lay such rugs next to rugs with undyed wools and the

effect seems the same as the pronounced abrash seen in the undyed

wools.

Regarding Bob's observation of the change in ground colors. This

seems separate from abrash. I have noticed this also, it appears in numerous

Kurdish rugs that we attribute to the Sauj Bulaq area. I think it is not abrash

because it is as if the weaver started with one ground color then switched to

another color rather than a more shading like effect that i associate with

abrash. I have no good explanation except I have observed it and wondered about

it as well.

Thanks, michael

Posted by Steve Price on

08-09-2002 04:37 PM:

Abrash - micro and macro

Hi People,

It seems to me that part of the confusion in this

discussion is that abrash has two meanings, and the two things it means

are very different from each other. This fact was noted by someone earlier in

the discussion, but continues to muddy the water.

Let me propose two

different terms for the two kinds of abrash.

1. Macro-abrash: This is

what happens when the weaver changes from one shade of a color to another,

either intentionally or because she ran out of wool in the first shade.

2.

Micro-abrash: Handspun wool is not of uniform diameter, nor is the dye

in a vat uniformly distributed along the surface of wool that's in it. As a

result, there is some variation in color intensity from place to place within

the skein of yarn. This appears on a rug woven from it as non-uniformity of

color within very small areas.

Perhaps this will help. Probably not.

Regards,

Steve Price

Posted by Vincent Keers on

08-09-2002 08:23 PM:

Macro Abrash

Dera all,

The changing ground colour.

Mostly from indigo into

black/dark brown.

For a light shade of indigo you dye one/two times.

For

a darker shade of indigo you dye five six times.

Indigo makes the wool

stronger.

So maybe they thaught: Lets dye it 8 times.

The result was

black/brown.

I sometimes see very dark, allmost black colours but

when I

look at them in bright sunlight, they have a toutch of blue.

If the black

ground colour looks more worn then the indigo

it's a different dye.

If

the indigo is worn and the black isn't,

well, maybe your mother in law likes

it?

Does this help?

Vincent

Posted by Patrick Weiler on 08-11-2002 01:32

PM:

Black and Blue

Kurdish rugs are not the only rugs with changing field colors.

Lur

rugs seem to frequently use this technique also. Perhaps because they were both

"poor, disadvantaged" tribes?

The Sauj Bulagh that Bob Kent showed has

the variation in field color from blue to dark blue to brown.

I have a Lur

rug that the field color changes so subtly from blue to brown that you almost

have to look closely to realize that it changed! There is no difference in

wear-depth, but I suspect the brown wool is an un-dyed wool so the wear

characteristics would be little different than indigo-dyed blue.

The main

border is the same blue as the field, but all the way around and does not

change to brown. Either the weaver knew she wouldn't have enough to complete

both the field and the border, or there was some other reason to change the

field color to brown.

Another Lur rug of mine has "striations" of brown,

along with some lines of lighter blue, intruding into the blue field, but only

on one side, not all the way across the field. This brown has receded

significantly, leaving an almost topographical effect on the surface of the rug

in that area.

A Lur or Qashqa'i gabbeh I have with a natural grey wool

field has overall changes in this ground color, making the design ornaments

appear to float above this abrashed grey background.

This leads to two

speculations.

1 The abrash effect may be purposely used with the intent

of causing this three dimensional appearance.

2 The natural variation

in the underlying wool colors takes up the dyes differently causing an inherent

abrash even if the wool is dyed quite the same. Rural or tribal weavers may

have not been as concerned as their urban counterparts about having uniformly

consistent white wool to dye for their rugs. They also may have either dyed the

wool themselves, or taken their own vari-colored wool to a professional dyer

who wouldn't have taken the time or had the large quantities of wool needed to

"grade" the wool into lighter and darker shades that would allow a more uniform

field color.

Patrick Weiler

Posted by Bob Kent on 08-11-2002

07:22 PM:

field color changes

hi: great discussion.... for what it's worth, these field color changes

are from blue to corroded black:

Posted by Filiberto Boncompagni on

08-12-2002 04:01 AM:

Yes, interesting discussion.

It’s the first time, if I well

remember, that this topic reaches some depth on Turkotek.

Thanks, Bob,

for your pictures. I believe change of color is intentional because that is the

most logical explanation - but that’s different from abrash (better: MACRO

abrash, as Steve points out).

About the intentionality of macro abrash,

the picture I presented above should be a good proof that, at least in same

instances, it is not a mere hypothesis.

What we need is more examples:

please, folks, have a closer look at your abrashed rugs.

Patrick, could

you please show us your Lur you refer with "The main border is the same blue as

the field, but all the way around and does not change to brown"?

Thanks,

Filiberto

Posted by Filiberto Boncompagni on

08-12-2002 06:10 AM:

Well, I found another one:

Boucher’s BALUCHI WOVEN

TREASURES, Plate 55, Timuri Rug, scan of a detail.

Blue field again (a coincidence?), with micro and macro

abrash.

Let’s focus on the macro one.

The common wisdom says the

weaver had only one skein of blue wool (well, not literally one, but I’m

trying to simplify).

The irregularity of the dyeing process produces a

skein with different intensity of blue.

The weaver didn’t give a damn

about it thus producing what we call macro abrash as we can see in, say, point

1 and 2.

However point 3 shows that she was perfectly aware of the

change of tone and she had to use an other skein with a different blue.

Regards,

Filiberto

Posted by Michael Wendorf on

08-12-2002 08:09 AM:

changing ground color and abrash

Hi:

I think the Timuri rug is an example of abrash that, in my

opinion, is not explained by conventional explanation # 1 or # 2. Like some of

the Kurdish rugs I was thinking of, the rug has super saturated dyes and is

made of the finest materials throughout. The effect of abrash seems to me to be

created by the weaver with the two shades of blue not out of carelessness or

sloppiness but by choice and to be much like the abrash we see in rugs with

undyed wools.

The rug Bob Kent illustrates with the 4 x 14 stars has the

change in ground color that I have also observed. Usually, I see this near the

top of the rug as it was hung on the loom. I have no explanation for this.

Patrick's observations are keen and the comparison of Lur rugs with

Kurdish rugs is interesting given both the proximity and isolation of some

groups. I think Jim Opie sees the Lurs much the way I see the Kurds. Regarding

the observation of striations, I observe this too but usually in Kurd rugs the

contrasting color - a line of blue in a ground that is otherwise brown - goes

the entire width. I have also seen brown put into long rugs with a field that

is otherwise blue.

And Patrick's speculations cause me to add that wool

colors have been sorted/graded for a long time. The most valuable wools are the

ivory wools and these can and are sold into the market by tribal/nomadic groups

herding sheep even today. I have slides of this happening in 1990 in eastern

Turkey. The darker wools may be sold or kept for home use. The use of these

darker wools and problems of pigmentation and dye may also contribute to the

ingrained aesthetic of abrash just as I believe the traditional use of undyed

wools may have. Thanks to Patrick for this point and which also is a further

extension of conventional explanation #1 posed by John about the way dyes

"take" to wools. Worth exploring further, I think. But it does not explain

abrash in rugs such as that illustrated by Filiberto where the weaver had

available, it would seem, whatever dyes and wools she wanted.

Thanks for

all the contributions, Michael

Posted by Filiberto Boncompagni on

08-12-2002 08:19 AM:

Bob,

I have to correct myself: the more I think about it, the

more I’m arriving close to your affirmation that macro abrash is pretty

similar to background color change.

Regards,

Filiberto

Posted by Richard Tomlinson on 08-12-2002 08:37 AM:

Hi all

Great discussion.

If we are to assume that weavers

deliberately created abrash, perhaps we might look for reasons why.

I

have read about attempts at creating 3- dimensionality. We hear and read of

'floating' motifs. Are they deliberate?

As most weavers would have lived

in a 'natural' environment, I was wondering what physical/natural features

weavers might have tried to mimic / copy? I might be naive to assume that

weavers would have to copy something they had seen, but it may be a starting

point.

Interested to know what others think.

**Please dont ask

me to explain what I mean here :-)

Rgds

Richard Tomlinson

Posted by Michael Wendorf on 08-12-2002 09:50 AM:

more on abrash

Dear Richard:

How about the landscape on the Anatolian plateau or

the Kurdistan plateau, or how about a night sky?

With regards to this

general discussion of abrash, I went back to Brueggemann and Boehmer's Rugs of

the Peasants and Nomads of Anatolia. Certainly Harald Boehmer has as deep a

knowledge of dyes as most anyone - or where is Michael Bischof - so it seems

worth considering some of his thoughts, at least so far as 1983 when the book

was published. The authors note that abrash has its origins in the Persian word

for cloud. see footnote 88 on page 117. Abrash is described as "the various

color nuances in one color-plane, even in a single knot." (Macro and Micro?)

they draw an analogy to blue jeans and the landscapes blue jeans contain and

note, consistent with the conventional explanations stated above by John, that

dye bath characteristics, the differing strengths of wool in hand spun threads,

differences in quality, fiber structure and grease (natural oils such as

lanolin?) content of the wool become evident in the dying : the long fibered

wool from spring and the shorter fibered from fall also take dyes differently

with different tones. Mordant dyes react more sensitively because variations in

mordant density and adherence of mordant to the fiber show up as variations in

intensity and shade of color. See page 117. He also notes water impurities as a

factor. Page 118.

Interestingly, the authors conclude that color

compensation, attenuation and abrash are principle components of the impression

made by colors of old rugs. Page 118 And that strong abrash is a characteristic

of nomad rugs. Page 122.

It seems that the micro/macro distinction may

be helpful to understanding abrash. On a micro level, we understand the

explanation for color changes. But what about macro, the use of abrash for

impression or expression by a weaver? And what about weavers who had the

ability to select whatever wools and dyes they wanted and who still inwove

variation/abrash? And how do we explain the abrash in connection with undyed

wools. I think the expanation of how abrash occurs - naturally in undyed wool

and naturally through the dying process as Patrick above and the authors

Brueggemann and Boehmer explain - still leads to the same conclusion, that

abrash in many rugs is intentional and, I would argue, the result of a long

ingrained tradition of using both undyed wools and/or darker wools that

naturally contain abrash.

Thanks, michael

Posted by Steve

Price on 08-12-2002 10:04 AM:

More on micro-abrash

Hi Michael,

I'll add one thing, specifically with regard to

"micro-abrash" (the color variation that can occur in very small areas, even

within a single knot).

Micro-abrash is nearly invisible except from

very close up, but even from a distance it has an effect. That effect is what

many collectors refer to as "life" in a color. One of the things that makes

modern rugs less attractive to me (and to many like-minded snobs) than old ones

is that the colors are usually "flat" or "lifeless" in newer rugs. This is

because there is no variation at all in the areas that are the same color;

there is no micro-abrash. I've never had any trouble getting anyone to

understand it once they are shown two rugs side by side, one with and one

without it.

Even very old Turkmen stuff, in which macro-abrash is quite

rare, have lots of micro-abrash. This is part of what makes their colors so

much more attractive than recent (Soviet era) Turkmen

rugs.

Regards,

Steve Price

Posted by Chuck Wagner on

08-13-2002 11:33 AM:

An CerebroFlatual Exposition

Greetings all,

Here's a couple thoughts to ponder:

Can, and should, the word “abrash” move beyond the notion of

a catch-all term describing variations in color that could have been

represented as a single solid shade ? Can abrashes be classified in an orderly

way, or should other technical terms be used to describe the effect precisely,

leaving abrash at the same level as car (as opposed to Chevy Lumina).

Whether we're talking about striping and/or banding of colors, or more

subtle features with diffuse and/or irregular distribution of colors, it seems

to me that it's the the SCALE of the color change: the contrast, that

determines the degree to which an abrash pleases, interests, or irritates us.

Certain processes and/or behaviors can be associated with certain scales, as

Steve has suggested (macro vs. micro, skein vs. strands, large batch vs. small

batch) and we start to categorize (and subdivide) "abrash" in our

minds.

But getting from there to a commonly understood frame of

reference, for the purposes of our discussions, is going to take some work. It

could be a salon all by itself: Tradition, art, chemistry,

commercialism,

laziness, error, random chance, time, and their impact on the

development of an abrash..

Some semi-formal classification would be

useful for us. Developing a list of the various factors in abrash development,

their causal relationships, geographic constraints, etc. It might allow us to

reduce the subjectivity to acceptable levels. But I digress (plus, I’m not

sure it CAN be done practically, and, you could probably do a masters thesis on

this topic)... I’m going to take a different approach in this

post.

(Filiberto said he wanted more examples. OK, so, here's where he

learns to be careful what he asks for, because he might get it...)

I

have arranged these images in decreasing order of what I will call "likely

abrash awareness" on the part of the weaver. I use that term because I'm not

happy with trying to assign levels of intent to the weavers actions. But, I

recognize the likelihood of an "a priori" understanding on the weavers part

regarding the likelihood of an abrashed result.

I shy away from intent

because I’m not convinced that the weavers always have a lot of control

over the quantity of wool (in a specific shade of a certain color) that is

available to them. Further, I believe that much color variation noted today is

at least partially related to the aging process, and may have been

imperceptible to the weaver at the time the work was done.

I also think

the conditions under which the weaving is done may have a substantial impact on

the development of abrash. Obviously, in dim lighting conditions one could

easily confuse similar shades of the same color. But: lay out at the beach for

a half hour with your eyes closed and pointed upward! When you get up and open

your eyes, your ability to distinguish between shades of red will be greatly

reduced. I suspect that outdoor weavers may frequently suffer from this effect,

and create an abrash unwittingly.

Several of you have already discussed

the impact of variations in dyes and mordants, drying time, etc. so I won't

dwell on that area. Add to all of the above the notion of intent (with a

variety of motivations) and things start getting complicated.

How one

determines which abrash is intentional, to me, might be addressed by looking

for APPARENT accident as opposed to REAL accident. We've seen one obvious case

above where the abrash failed to extend cross a border. I'll describe an

extreme case: I have seen Gabbeh-look-alikes on the market that are knotted in

alternating shades of similar colors. The wool in each knot is consistently

shaded, but the knotted shades alternate rapidly and ALMOST randomly. To an

inexperienced eye, the effect is similar to that on a genuine vegetable dyed

Zollanvari Gabbeh. To me that's not what we would call abrash, it's a gimmick.

But it's definitely intentional.

A better, but still gimmicky,

intentional approach is seen in modern Kawdani prayer rugs, where tan and light

gray wools are mixed to present an appearance similar to that of camel hair.

Pleasant, subtle, and highly variable but contrived nevertheless.

These

are extremes brought on by commercial considerations. I'll start with obviously

intentional abrash, but with appearance as the motivation (I think) rather than

mimicry or commercialism.

This is an odd one from Afghanistan. On the

creature's left, abrashed wool. On its right, abrashed raw silk. (Try to get

over your jealousy. We can't ALL have a rug with barnyard animals in the main

border.)

Next, an older Baluchi with a few scales of abrash. It

looks like there were several batches of wool that went into this one; the most

obvious change is to the right. It's even present in the kilim end.

Now

a Qashqai, quirky but one of my favorites. Lots of variation in the field, but

not so full of contrast as to be irritating. Probably due to small batch

dyeing?

There is no way she didn't know about this.

But I wouldn't categorize this as First Degree Abrash. I don't think it was

planned, it just grew this way.

Here's a Yomut chuval with some

abrash in the field color...

The abrash striping is almost

imperceptible on the inside, a small shift to a pink shade instead of red. Is

this dye batch, or lighting conditions at work ?

This pre-WWII Afghan Sulayman is dark red. It's easy

for me to believe that this abrash is simply a result of materials and lighting

with no intent on the part of the weaver.

The

same is true for this Afghan Hazara kilim...

And the changes in shade on this Afshar are often so

subtle that they're not visible from a short distance, the brown in

particular.

Somewhere, from the top to the bottom of these

images, we transitioned from intentional to unintentional color variations. The

technical reasons for the variety are separate from the motives of the weaver

in my mind. A structured approach to this issue MAY be useful for attribution

studies, etc.

Let’s find a grad student to do the

work….

Regards (and thanks for putting up with my

rambling),

Chuck

__________________

Chuck Wagner

Posted by Sophia Gates on 08-13-2002 03:51 PM:

Commercial Art?

Dear Chuck and all:

Chuck, thanks for your well-written &

illustrated post. There's a lot to discuss there but I want to focus primarily

on one statement/connection you've made - that between "commercialism" and

"contrived effect".

Where to begin! Folks, "contrived effect"

practically defines what the visual artist DOES. I'm extremely curious as to

why that is supposedly a sign of commercialism as opposed to what: Soul Baring

Deathless Masterpiece Making? Regardless of the end purpose of a piece - floor

rug or Future Museum Piece - the process of creating it, getting the best use

out of one's materials, is the same.

Effects are created in order to

produce effects (duh), communicate ideas, make things look more interesting,

add variety to limited materials, etc.

Chuck mentioned gabbehs. I'm

curious, did any of you see the movie, "Gabbeh"? In that film, a beloved child

dies while chasing her pet goat up a cliff. The weavers, her family, are grief

stricken and weave their sorrow into a gabbeh in the form of a dark abrash

against the dappled reddish background of their rug. Definitely, a "contrived

effect"! Using a streaky black & brown color to make a statement - a

deliberate use of color to reflect and create an emotion. What difference does

it make if the gabbeh wound up being sold, was perhaps planned and made to be

sold in the first place? The Old Masters didn't paint for laughs either. They

accepted commissions and got paid for their work. Are they commercial artists?

If so, who cares?

Secondly - Chuck is correct about the effects of

sunlight on vision. However, almost all of the photos of weavers I've seen show

them weaving under a sunshade of some type - inside a tent or pavilion - even a

house - under a tree - practically a necessity I should think, considering the

brilliant light of the deserts and mountains - I can't imagine an intelligent

human being trying to weave in brilliant sun without some shelter! Surely they

too would have been aware that sun is literally blinding. These weavers by

definition were extremely aware of, and sensitive to, subtle nuances of color.

It was a part of their world, a survival mechanism: this grass is bad for the

animals, this is good, that color cloud means rain, these flowers are good for

dyeing, this earth is fertile, this is salty - so forth. It is we who are

losing our sensitivity!

We're influenced more by the colors on TV, the

brilliant, Dayglo packages on the shelves of our stores, than by the dictates

of survival in a natural setting. I recommended a particular opaque watercolor

paint set to a student recently, a German brand I've used since childhood. I

had to laugh when I compared her set to mine, which is about ten years old - in

place of some subtle natural earth reds, a brilliant dayglo pink and magenta

purple had been substituted. Time marches on!

Anyhow, some

thoughts.

Best,

Sophia

Posted by Richard Tomlinson on

08-13-2002 09:42 PM:

Hi

It's been argued that 'subtle' changes ( e.g. the abrash in

the brown wool in Chuck's last image) is unintentional.

I am not arguing

that all abrash is intentional BUT...

I believe the fact that weavers

often include a SINGLE knot that is a different color (and I'd welcome any

arguments for that being unintentional) might be proof enough that even the

most subtle of changes MAY be deliberate.

Thanks

Richard

Tomlinson

Posted by Patrick Weiler on 08-13-2002 10:49 PM:

The Lur's

This first photograph shows a closeup of the Lur rug with the field that

changes from blue to dark brown, even though the main border is the same blue

as the field but all the way around. The bottom 2/3 of the field is blue, but

the top 1/3 is very dark brown. It is a large rug and the change in field color

is almost not noticeable and certainly is not disruptive to the overall impact

of the rug.

I only took this one photograph of a chicken with what appears

to be a rooster standing on its back. I am traveling and can not photograph the

entire rug, but this photo shows the demarcation line just above the back of

the chicken.

This next photo shows an entire

Lur rug with the brown striated abrash that only occurs in one small quadrant

of the rug. You may be able to discern a line of lighter blue just below

mid-field. The left half of the rug below this line has brown, oxidixed rows of

knotting entering the field, but only on the left side of the

field.

The next photo shows the area containing the most brown

knotting:

This final picture is a close-up that may

allow you to appreciate the variation in depth of the surface caused by the

oxidation of the brown wool:

This is a serious example of macro abrash, with sculptural

effects thrown in for good measure.

Why was the brown only used on a small

part of the rug? Why on only one half and not the other? How does this

situation fit with the theories being postulated in this salon?

Patrick

Weiler

Posted by Steve Price on 08-14-2002 09:27 AM:

Hi Folks,

I've been promised a Salon essay devoted to abrash, to

open in December or January. That doesn't make it improper to discuss abrash

here, of course; I just want to alert everyone to the fact that it's coming up.

It does suggest that it might be best not to expand the range of the present

discussion of abrash too much.

Regards,

Steve Price

Posted by Filiberto Boncompagni on 08-14-2002 09:57 AM:

Hi Steve,

I already prepared this one - well, anyway it’s

short:

Thanks, Chuck,

Are you volunteering to find that student? He

(she) could help for the Salon on abrash.

Thanks for the pictures (to

Patrick too).

My opinion: let’s forget the micro abrash. This is

present also on old Persian workshop rugs.

On the other hand: macro

abrash, color changes (it could be in a few knots only, or in a short row, or

in a huge section), abrupt changes in borders size or in border decorations -

in short all the irregularities we can see in rustic/tribal weaving have been

discussed very often here… Still, we cannot find conclusive evidence of

why the hell they made them.

I think, at least, that most of them are

deliberate.

I find that Michael’s explanation for the macro abrash is

a very good one.

Sophia, I didn’t know that "Gabbeh" movie - I had

to search the web for it.

The idea of "The weavers… weave their sorrow

into a gabbeh in the form of a dark abrash against the dappled reddish

background of their rug" is interesting.

It has to be seen if it came from

the Qashqais or from the movie director,

though.

Regards,

Filiberto

Posted by Michael Wendorf on

08-14-2002 10:07 AM:

color attenuation and synthetic/natural dyes

Hello Readers:

Going back to Chuck's post, I think he raises some

critical issues concerning the very notion of abrash and what it

means/represents. It seems to me we often talk about abrash without knowing

that we are all talking about or even observing the same thing. And whether we

think about abrash as one of the reasons we like the color in certain rugs or

as a marker for a type of rug or even as part of a long tradition, we need to

be clear on what abrash is and is not. It may well be that abrash is several

things with several explanations.

Chuck's post also raises another

issue. To my eyes, most of the colors in the rugs Chuck illustrates appear to

have synthetic dyes. Can abrash as we are discussing it be an effect when

synthetic dyes are in use. The issue is not one of snobbery. Going back to Rugs

of Anatolia again, Brueggemann and Boehmer make a critical comparison of

natural and synthetic dyes beginning at page 117. They conducted experiments

with both natural and synthetic dyes and note that synthetic dyes are available

in all colors but that all these dyes are based on combinations of only the

three primary colors - blue, red and yellow. Because use of only the primary

colors is harsh or discordant, the only colors were developed and used, they

call this "color compensation" - a way to make the primary colors less harsh or

discordant. In other words, an attenuating or abrash like effect is used to try

to harmonize the synthetic colors and make them less strident and, as they

experimented, to try and match old natural colors. They then state that this is

not an issue with natural dyes since each color is already inherently muted and

color-compensated. They also point out that by mixing synthetic dyes nearly any

natural dye color can be imitated but that some of these pieces suffer from

"over-attenuation" because some of these dyes are light sensitive and others

are not.

Finally, they state: "Within wool dyed with a synthetic dye

there are hardly any varying color shifts towards neighboring colors; what is

missing is called abrash."

Regarding Patrick's brown knotting and

sculptural effect and the change in ground color Bob Kent has pointed out - do

we really think of this as abrash? Perhaps we need to find another term to

describe these observations. I go back to the roots of the term "abrash" and a

sense of cloud - which I infer relates to subtle color change within the same

color family. I think what you and Bob Kent have focused on is valid as more

examples of what Sophia has described as "contrived effect." I just am not sure

we want to call it abrash.

Thanks, Michael

Posted by Bob

Kent on 08-14-2002 01:11 PM:

different thing, same weavers?

Michael: I don't really see field color change (here, blue to

corroded-away black in Kurdish rug) as a form of abrash. But if Kurdish weavers

seem to appreciate 'macro abrash,' they might also appreciate this stronger

form of background-color change?? See ya, Bob :