Posted by Steve Price on 05-08-2002 09:09 AM:

Textile Art and Its Context

Dear People,

Michael has pointed out to me that several of the messages in the thread entitled "If you can't wash it, how

do you clean it?" really have nothing to do with washing, but concern textile art and its context. He asked

me to create a properly titled thread for those messages, and to move them into it. This thread is my attempt to

do that. Let's see how it works. The messages that I am copying into this thread also appear in their original

positions in the "If you can't wash it..." thread. I hope this doesn't create confusion.

Steve Price

Posted by Sophia_Gates on 05-08-2002 09:15 AM:

This post appeared originally in the thread, "If you

can't wash it...". It is still in that thread also.

Provenance & Art

I think the authors of this Salon seem to have posted valuable information concerning the damage and de-stabilizing

effects of time & improper washing on dye-lakes. Many of us have personally observed bleeding in very old pieces

and finally this would seem to be a logical explanation of why that can occur.

On the other hand, I fail to see what provenance has to do with art. Beauty and creativity have nothing to do with

the ownership of an object after it's been made. Nor has The Scientific Method anything to do with the esthetic

experience.

Art just "is" - like nature. They can be examined but not "proved". You can't "prove"

beauty! You can't "prove" profundity or magic. And who's to say that the fantasies you reference aren't

in fact psychological truths? "Reality" is indeed far more complex than a shallow, simple-minded reading

would indicate - and THAT, science can and has been "proving".

Posted by Steve Price on 05-08-2002 09:18 AM:

This message originally appeared in the thread, "If

you can't wash it...". It remains there also.

Hi Sophia,

You raise several points, and I would take issue with some of them.

Start with, Art just "is" - like nature - that is, neither is subject to proof (of, I assume, the truth

in an interpretation; if this is not what you mean, then proof of what?). Within certain constraints, our interpretation

of natural phenomena is most certainly subject to proof. The tests are not flawless, but are far removed from "it

just is". Lightning has an explanation that is almost surely correct. I doubt that you would offer "it

just is" as an explanation. The same applies to the basis for inheritance, the fact that apples fall down

and not up, and so on for as long a list as you would like to make.

As for psychological truths, what does that mean? If it means the things that psychologists consider to be the

facts of their discipline, then you are talking about something that is arrived at by the scientific method, not

something external to it. If it means the personal beliefs that we hold but for which we cannot offer evidence,

then you are talking about truths that are entirely personal to the individual. Fantasies, no matter how fervently

someone believes in them, are not truths to anyone else. That, of course, is why we call them fantasies to begin

with.

I agree that aesthetics is currently outside the realm of science and I suspect that it will remain that way for

the foreseeable future. But there's lots more to art appreciation than aesthetics. One element especially relevant

to oriental rugs as art is their ethnographic and cultural significance. That is unknowable without knowing which

culture a piece came from, an element within the broad category of provenance. This, I believe, is what Michael

was talking about in his essay when he raised provenance as an issue.

And, whether we like it or not, collectors will ante up more money for an old piece than for a new one, and attribution

would be important for that reason even if it had nothing to do with aesthetics at all. That's why there's money

in faking old pieces, and in inventing fantasy criteria of age, and it's why it's worthwhile for a collector to

know something about recognizing them.

Regards,

Steve Price

Posted by Sophia_Gates on 05-08-2002 09:21 AM:

This post originally appeared in the thread, "If you

can't wash it...". It is still in that thread also.

Old Rugs

Steve, I'm not going to get into another defense of Art right now! I simply lack the energy. However, I will say

this: proving that certain conditions might result in lightening do NOT explain its existence, any more than Big

Bang theories explain or prove the existence of the universe. That's an area to my mind more in the realm of metaphysics

than of science - indeed, perhaps, attempting to explain MAN LIGHTENING UNIVERSE STARS. . . is still the business

of artists.

I will admit it's been fashionable for the past few centuries to regard Science as God. But that's another story!

I understand your point about the cultural significance of tribal artifacts; however, I submit that their value

as art is continuing long after their cultures are dead & buried. Why? Because that is one of the characteristics

of art: it can transcend its period and reach out to humans across spans of time, race, religion and culture.

However, I wholeheartedly agree with you about the market for old rugs. I suspect, if collectors had more self-confidence,

and if esthetics were indeed more important than age & provenance, if in other words people had more innate

understanding and respect for Art, then we'd be perfectly happy to go out & buy newer pieces. Why? Because

some of them are excellent. Some of them are dreadful. But - all in all they sure are cheaper!

Some old pieces are dreadful also. We tend to see the past via the glories of hindsight: much of the dreadful has

already been discarded, so we get a distorted view of the glories of the past.

I suggest that we start buying rugs as if they were new, with as much critical faculty as we can muster. Really

LOOK at them: are they really beautiful or do we merely think we're discovering some new design in an old rug (high

unlikely, I think, given the highly conservative nature of, especially, tribal rugs) Is the thing well-designed

and well-proportioned or is it just strange? Does is REALLY speak of Ancient Shamanic Mysteries or is it just out

of proportion?

And did I actually hear Wendel speak of "intuition" when he said he was thankful he'd avoided purchasing

a New "Antique"? I agree with him! That might actually be one of our strongest tools for avoiding bad

rugs & bad art: that nagging feeling that Something Is Wrong. Maybe it's the design, maybe it's the composition

of the field; maybe it's the relationship of field motif to negative space. Maybe the field motifs are too big

for the border. Maybe that red shape should have an outline of brown?

In any case, I think listening to that little voice called Intuition is a Really Good Idea.

It appears we've entered an era in which we might actually start looking for small knots of faded fuchshine in

order to reassure ourselves that our treasure is Really Really Old

Why not just buy it because it's Really Really Wonderful?

Posted by Steve Price on 05-08-2002 09:25 AM:

This message originally appeared in the thread, "If

you can't wash it...". It is still there also.

Hi Sophia,

I think we are at an impasse on the interpretation of natural phenomena, so let's leave it alone. And obviously,

I think, we have no common ground from which to discuss interpretation of anything else since we differ so widely

on how to decide whether an assertion is fact or fancy.

Regards,

Steve Price

Note added a few hours after initial posting: In reading my message again, it looks as though it might be interpreted

as a dismissal of Sophia and her thinking. That is not my intention. I disagree with her in the same way that,

say, a Christian and a Jew disagree about whether Jesus was the Messiah prophesied in the Old Testament. Most Christians

and most Jews simply agree to disagree, and don't argue about it. This is my position vis-a-vis my views and Sophia's

about criteria for truth.

Posted by Michael_Bischof on 05-08-2002 09:28 AM:

This message originally appeared in the thread, "If

you can't wash it...". It remains there also.

knowing the origin

Dear Sophia,

excuse my late answer, please. You wrote "Art just "is" - like nature . They can be examined but

not "proved". You can't "prove" beauty! You can't "prove" profundity or magic. And

who's to say that the fantasies you reference aren't in fact psychological truths?" and to know the real origin

of a weave does not contribute to the evaluation of its artistic qualities.

I believe in moving close to the subject. Look, please, at pl. 28 of the McCoy-Jones kilim collection in San Francisco.

This kilim was admired by a lot of people at the ICOC as being bold, archaic, creative etc. like to art that just

is. - If you take this piece to the Orient and show it to whatever kilim weaver you will see that every lady will

laugh and firmly state that this kilim is a mishappened weave. May be no talent, no motivation, other things to

do in life so one could not further think of this piece on the loom.

You, Sophia, have the human right to conitinue to adore it : but it is not art then. And then look at the kilim

pl. 24 of the Rageth book on radiocarbon dating of kilims. At its source every weaver will admire it ( it is a

good example of washing damage, especially to its "minor dyes" so washing damaged its aesthetic quality

by artificially unbalancing the colour

harmony a bit). This is no proof that it is art, of course.

Then imagine a beautiful Buddha statuette appears on the international art market. Its origin

is unknown, most likely Angkor Wat. Apparently in this case not to know the real origin does not handicap the evaluation

of its artistic merits.

Where does this difference come from ? For Buddha statuettes some hundred years of independant ( from the art market)

research has set up a kind of intersubjective standard of measure to evaluate the quality of these artifacts. To

place a new arrival properly into this frame is more or less easy ( this example I owe to a discussion with Dietmar

Pelz).

For early kilims and village rugs we did not establish yet such a set of measures. We just start to reserch them

properly. There is only one group of kilims where we know what for they have been made so we can start to discuss

what seems to be a successful aesthetical solution and what should be regarded as a minor one. Therefore it is

essential to know the original context of a weave as good as one can ! No word against intuition and phantasy.

But if these

are not balanced by knowledge they are convincing only to the single person that displays it.

Compare it to how you would build a house. Firm ground is essential, yes ? This knowledge

about the origin is the only part of firm ground to start with. In case you do not have even that any derivative

thought is free floating - and not more "firm" than that.

Regards

Michael

Posted by Sophia_Gates on 05-08-2002 09:31 AM:

This message originally appeared in the thread, "If

you can't wash it...". It is still there also

Origins, Etc.

Dear Michael:

Your points are well-taken. However, the fact that some Middle-Eastern ladies laughed at the McCoy-Jones kilim

means less than nothing. A good study of the history of Western painting would reveal many cases of people laughing

at great art. One has only to go back as far as the 19th century to read the comments of the French Academy about

the Romantic & Impressionist painters. And we know all too well the tragic story of Van Gogh, an artist of

enormous passion and originality who never sold a piece and died broke and discouraged by his own hand.

I regret constantly having to refer to the history of painting in order to illustrate points about rugs. However

as you have pointed out we're still just learning about rugs and haven't the wealth of knowledge concerning them

- and I doubt we ever will have - so I hope you'll forgive me for reintroducing Art-As-Painting into these discussions!

To my mind, your attempts to make accurate assessments of age and origin, to establish a sort of baseline, are

valid. But they will still not establish whether or not a piece is "art"! And as far as Steve's argument

concerning "cultural validity" - that too has merit but is fluid as well: consider the validity these

old pieces have now assumed, through our collection and studies of them, to our own culture! Indeed, the little

white ACOR piece has attained some importance by virtue of its controversial origins as well as its inclusion in

the ACOR show. As a matter of fact, the actions of today's collectors may well establish which pieces are regarded

as important generations from now.

Additionally, your comments on wool and dyes and the nature of dye absorbtion are fascinating and most welcome.

And, as a practical matter your approach to limiting the most stringent approaches to restoration to only a small

number of pieces does make sense, although to my mind ALL the old tribal pieces have value as cultural artifacts.

Indeed, my own feeling about restoration is one of wariness, for fear of ruining a piece.

Finally, your assessment of the big kilim you restored is certainly beyond question, to my mind. I think it's wonderful,

although like Vincent and Yon I don't see why a new one couldn't have been made - but the weaver's decision to

use that dark, dark color in the background was brilliant. It's a beautiful piece and I'm sure we are all delighted

to have shared it with you.

All the best,

Sophia

Posted by Michael_Bischof on 05-08-2002 09:34 AM:

This message originally appeared in the thread, "If

you can't wash it...". It still appears there also.

Dear Sophia,

nothing against transferring my examples to paintings. But you must transfer it in the right way - like this:

Not the people laughed about the painting ! All painters , persons who had learned the techniques of how to paint,

laughed about the painting. But 10 000 kms away, where even the most advanced connoisseurs do not understand much

of even the most simple primaries of how to make a paint, the majority of people admired this crook painting as

"creative art" !

May be a lot of painters found the technically "good" picture ( pl. 28 in Rageth) technically perfect,

but boring and uninspired, but they accepted it as a painting.

We often heard in the fifties such jokes about Picasso. But he was technically well educated

- he did not want to paint like the majority of his contemporary colleagues though he could have done that as well.

With this view pl. 24 of McCoy-Jones is a mishappened kilim and under no perspectives

such a thing can be regarded as art whereas with pl. 28 of Rageth such a discussion would make sense.

The prejudice that it is not important to know the real origin ( and that means: to have, at least theoretical,

access to the context in which the weave was made) of a piece often has

funny consequences. One example for how easy people with this attitude can be fooled - and the ACOR minder is another

example:

In the nineties a big international firm wanted to create rugs that should be perceived as "creative"

by its customers. They were done in big workshops, for example, in the vicinity of Nigde. Female teachers, paid

by the Turkish government, supervised the work of the weavers. We visited the place. Then we saw things that every

weaver in Anatolia would regard to be a mistake ( motifs that are drawn wrong, design elements not placed in the

middle of the border but lapping into the main field, intentionally made irregularities...) and asked the weavers:

what is this, please ? They fell ashamed but said the design and the teachers forced her to weave these mistakes.

Not that she does not know that it is a mistake or that she could not it better. But the patron wants it like that

...

And now you have to accept - I mean you must, no alternative left for you - that this merchandize was marketed

very successful in your country just by claiming that it is real creative weaving. Independant of further discussing

things here the approach to textile art that you follow can be fooled that easy !

The same with this white ground minder at ACOR.

It is immediately evident that the design is "wrong". No weaver would do such a thing.

Such a minder has either a 1-4 symmetry or a field with small repetitive patterns or is left blank - but never

ever this design ! This is an ironic joke that Oriental people made about the perception that some Western people

have about simple, bold designs. And as long as scholars refuse to interprete this textile art within its context

( and this unavoidably will always start with getting to know the real origin) these jokes will go on.

Yours sincerely

Michael

Posted by Bob Kent on 05-08-2002 09:58 AM:

sophia: "if collectors had more self-confidence, and if

esthetics were indeed more important than age & provenance..."

I think the key part here is confidence. Yes, extra-aesthetic concerns such as age (confounded with aesthetic issues

but a collector hot button on its own), provenance (famous collection, name dealer), commercial/ noncommercial

nature of object (somehow divined), rarity (part of the collector's bug, but extra-aesthetic), cost, construction/materials

issues, etc., can harden into overly influential criteria. But aesthetics are probably still more important to

most than age: who buys something old and ugly? (maybe I shouldn't be the one to ask that.) Also, like extra-aesthetic

dimensions, aesthetics as they are handled in rugdom can harden into smaller sets of issues or triggers (crowded

drawing, certain colors, "you want to look for this-," "this or that is the best of its type-, "this

design is successful (?) and that one is degenerate (not successful?)-") sorts of rules also. Aesthetics handled

in this way can become too top-down, also.

Of course it is important to understand the market tendencies on the extra-aesthetic and aesthetic things so you

don't pay too much and see if others' aesthetic preferences work for you.

Posted by Vincent Keers on 05-08-2002 11:54 AM:

Michael,

Think most oriental people know less about rugs then you do.

This 1-4/1-3/2-5 etc. design is available everywhere you look. Allready in antiquity.

So who ever made the Acor item wasn't educated in design. Oriental or western.

Best regards,

Vincent

Posted by Michael Bischof on 05-08-2002 12:15 PM:

Hallo Vincent,

I agree. But the person resp. the person who ordered it to be done like this was educated in what the potential

would like to see. I referred to what I would call "habits" of weavers. These habits have no logical

reason. But if they are there this specific design will immediately be recognized as somehow "wrong".

Rugs are and were a kind of intercultural thing anyway.

I have been told that the best specialist for upper Bavarian rural furniture painting is an American lady that

lives near the shores of the Starnberg lake - and I find this normal. For the "aborigines" their paintings

are a normal part of daily life so there is no reason to think too much about it. The same attitude one has in

the Orient.

When foreigners come to move close to carpets then they are starting to focus on it and think about it. Therefore

the result is an intervention and something like "back to the roots" is a romantic or a marketing phantasy.

Regards

Michael

Posted by Sophia_Gates on 05-08-2002 01:30 PM:

This message was moved from the thread, "If you can't

wash it..."

Michael,

Your description of the so-called creative weaving workshops is hilarious.

BUT - I again do not believe that art, emotionally charged and creative art, is merely a matter of not making mistakes.

And the French Academics who were laughing at the Romantics and the Impressionists were laughing at painters like

Delacroix and Manet and Renoir and Degas - all masters as well, who had CHOSEN a different route to expression.

If art is simply a matter of not making mistakes, why do we bother with hand-made art at all? Why do we not simply

buy machine-made carpets?

Finally - back to the weaving workshops: in this case, as in the Persian city workshops, the weavers are carrying

out the orders of the designers. The creativity in these cases is largely the fruit of the designers and not the

weavers. In these cases it is the designers, not the weavers, who must be considered the artists because they are

the ones with the ideas - for better or worse.

Could you arrange to show us the plate you refer to?

And many thanks for this stimulating Salon.

Best,

Sophia

Posted by Michael_Bischof on 05-08-2002 01:34 PM:

This message was moved from the thread, "If you can't

wash it..."

Dear Sophia,

the compliment for the stimulus goes back to you ! I am conservative. I did not say who makes no mistakes creates

art - I stressed that a person who is not able to command the technical basics of his enterprise cannot make art,

if remote people that try to sense art independant from their education and knowledge appreciate their result or

not. The impressionist painters did not make basic technical mistakes like it happened in this kilim. I am not

able to copy the plate from the McCoy-Jones kilim catalogue, sorry. It is pl. 24. And believe me, I remember it

well: it collected a lot of appreciation for being "bold art" whereas here I argue, as I did at that

time, it is nonsense.

In the Essen exhibition catalogue there are two of those bold pieces ( one is published in Ignazio Vok's Anatolian

kilim book) who give a good example for real "bold art", without apparent weaving mishappenings.

And I believe that something like having the idea cannot produce art. In the workshop system the designer has the

idea, the weaver makes stupid robot work. For me this is no textile art - no unity between brain and hand, no dialogue

between experience with the materials, collecting and developing the ideas that fit to the materials and to the

process ... just status showpieces of high technical perfection. The closer I move the more boring things develop

to be, whatever fascinating their command of techniques and high value materials have been ( superb professional

dyes, for instance - but no art).

What exactly means "hilarious" ?

Regards

Michael

Posted by Sophia_Gates on 05-08-2002 08:13 PM:

Weaving Workshops

Dear Michael:

I meant, your description of the poor weavers having to carry out the designers/dealers bad ideas was funny - not

that the situation is funny!

Fundamentally I think I agree with you concerning the connection between mind & hand. However, two things concern

me about this idea: where do we put the great Persian workshop carpets? Aren't they art?

And more on a philosophical idea perhaps, the past 50-plus years in Western art have seen the birth of Pop Art,

in which soup cans became immortalized, etc. And now we have Computer Art, in which the hand disappears altogether.

Personally I resent this! It bugs me that some kid with a mouse and computer can whip out "art" whereas

yours truly had to sit by the hour, by the day, week, month, YEAR, drawing from the model, mixing colors on little

cardboard squares, copying Da Vinci, etc. etc. But philosophically, if a creative act is involved, I reluctantly

have to say, computer art & soup cans etc. are art too.

But I don't have to be happy about it!

Best,

Sophia

Posted by Steve Price on 05-08-2002 10:10 PM:

Hi All,

I think part of the reason people are getting hung up here is that the word "art", not looking like a

plural noun, is leading the thinking along the lines of a monolithic concept.

In fact, as we all recognize, there are many genres of art and - this is important - it's perfectly OK to be a

lover of some and indifferent to or even repulsed by others.

Mainstream oriental rug collecting focuses on ethnographic textiles. The genre is as different from Persian court

rugs as the work of an individual sculptor is from the Notre Dame cathedral in Paris. The ethnographic textile,

like a piece of sculpture or painting, is essentially an expression of an individual artist, shaped and limited

by her cultural milieu. At least, that is what we collectors would like it to be. As Michael points out, it's often

the expression of a designer's notion of what a foreign market will prefer. The Persian court carpet is very different.

It is not the expression of an individual, it is an item designed and constructed to please a third party, just

as the cathedral is designed to fill the visitor (or worshipper) with awe by its scale and opulence. Direct comparisons

of tribal or rustic weavings with Persian court carpets simply don't make sense, any more than comparisons of a

Rodin sculpture, a Picasso painting and Notre Dame do.

Regards,

Steve Price

Posted by Filiberto Boncompagni on 05-09-2002 03:32 AM:

Anonymous posting

We received this message without signature. I’ll post it anyway,

inviting the anonymous contributor to send me his name, so I can post it again under it.

Thanks,

Filiberto

This message came from Eden Ethan, in Singapore, and entered the system without her name attached for some reason.

Thanks Eden.

Steve Price

Hi, being a novice in collecting, I am rather intimidated

to post my comments but this particular topic is just to exciting and challenging to let the opportunity pass.

Firstly, a question I would like to ask is how does one define art? What is art? If there is no common understanding

or discussion on this fundamental ground, it may be difficult to understanding the comments the other person gives

or why does the other party think the way he or she does.

A very valid point was brought up by Sophia..(if I remember correctly..) about soup cans...exactly !! How do you

define art? In fact, art (particulary modern art, installation art...) is out of the control of the 'common' person.

The "artist" says that his pee is art because he is an artist and if you don't agreed with that you are

entitled to your opinion. But the fact is people will be willing to fork out money to buy ash and ashtrays because

the artist said it is art and I am very sure any pee from me would be vulgar and the one way ticket to the psychiatric

session, and if this was done in public (in Singapore...) I will be in the papers, not the art section but the

criminal and charges (possibly under biazzare acts of outrage of decency.)

Indeed, just as Steve has appropriately countered with the many different genres of art. Is there a common consensus?

If the art has to be an individual's idea and effort...then the pieces of rugs and carpets in workshops will not

be recognised as such...how ever, many of the antiques that we see in books and auction catalogues are products

of workshop pieces ... so are they art? What about a simple, humble piece of weaving by the tribal lady...there

is integrity of the idea, effort and expression.

But is it ORIGINAL? If originity is another factor, then the many traditions adhered to by the tribal weavers are

in fact a handicap. But wonderfully argued by Michael in relationship to the American artist in Bavarian furniture

painting. The foreigner comes and elevates them to art. But the nagging feeling remains: if the weaver makes excellent

quality pieces that are regarded as art by the outsiders, those in the tribe would recognise them as what they

are wouldn't they? (This is essentially different from Western art whereby there is breaking away from schools

and the individuals' desire to express through his or her works. In traditional weaving, "please correct me

if I am wrong", the tribe that weaves in a particular way or uses a particular knot would not change because

one person decides to try something different. That is why, we could, or the experts can because I can't, identify

the identity of the piece and attribution.)

Then comes provenance. I think provenance is only useful when you are trying to sell the piece for a handsome price

and when you feel like stroking your ego. Does provenance add or subtract to the beauty of the piece? People pay

for provenance and age. Would people pay to buy old but ugly rugs? I don't really know but I would assume that

the fact that it is ugly would be factored in the price together with the age.

So, if this discussion could only bring us closer to how do we define 'art' in rugs and carpets, I think this would

be most satisfying and fruitful salon. The way I look at it, art is art because someone with the credentials said

so or those with lots of money are willing to pay for them. Sophia may violently disagreed because the esthetic

integrity is totally out of the picture. But the truth be told, art exists only and only when you have a majority

and that majority is willing to back up with action (paying top dollars for "top" pieces).

If art is reduced to beauty in the eye of the beholder then it simply narrows down all discussion, intellectual

to an over simplified exchange of one's personal comments, feeling, taste, liking. Either that, or everyone is

entitled to be the "tyrant' of art naming, passing out credentials to pieces of rugs and carpets. The paradox

lies in that the person who dislikes the idea of provenance is in fact, becoming the very "authority"

to convene approval that is in actual fact, contributing to "provenance" since anyone who finds something

beautiful is entitled to name it as art disregarding what others think.

Posted by Michael Bischof on 05-09-2002 04:35 AM:

Thank you, anonymous, for this wonderful contribution! With one hand you opened too many threads ... let me come

back to this kilim.

Often people stress that "tribal" art is bound to tradition and that there is no space for individual

creativity, no word for it and no concept. Since eternity they express mythic contents ... if one moves close to

such a society (one lives there and works with people there) this idea fades quickly. Weaves are recognized individually

and are remembered as having been made by this or that person under certain circumstances. When a border in a semi-antique

piece seems to be a bit out of order the lady that got this piece from her grandmother will explain: in this year

my grandmother Ayse was close to be engaged. So .... (laughing) . Or one realizes a new motif in a certain type

of rug that does not occur in 10 or 12 pieces of that particular "type". Then the weaver remembers: yes,

at that time my girl friend Fatma, feeling bored at home, came and she proposed a new motif for the border ...

She showed to us this motif, we liked it and put it into this carpet. From then on we preferred this to the older

motif.

To catch these stories in the Orient is difficult. It is impossible for tourists who drop to have a short walk

around in a village in for 1-5 hours , take some pictures and then go. For women it is easy to contact women, for

men it is not. If the woman can weave herself it is much easier ...

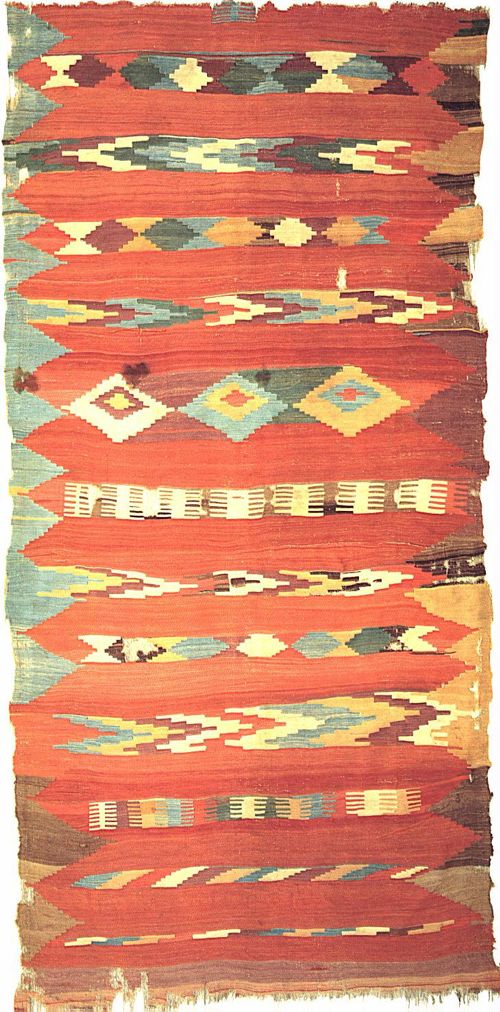

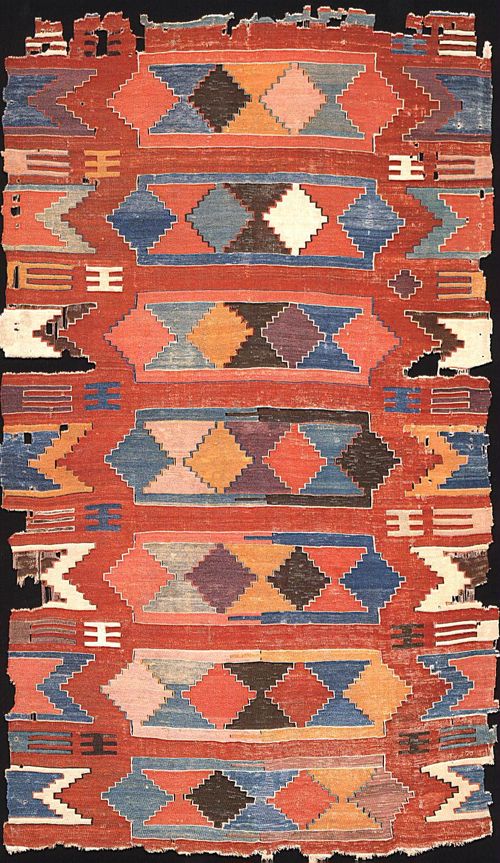

Here we have shown a habit of framing kilim motifs that is common in a certain area (Eastern part of Central Anatolia:

look at pl. 10 and 12, but we could present much more examples).

Notice, please, that pl. 12 has the same basic design scheme that this restored fragment has. The positive-negative

concept that is the primary underlying scheme of most early kilims is not very clear with pl. 12. By applying the

one simple decision to change the ground colour from red to black and to do this frame in white-red all over the

piece (instead of applying different colours for that purpose as it is the most common habit) this primary concept

becomes much clearer (Black "arrows" that point to the center of the kilims and white "arrows",

their bases connected to a hexagonal motif, pointing to the opposite direction) and the flatweave seems to achieve

a kind of third dimension. If the weaver of this particular kilim once had this idea or some earlier weaver we

cannot know (yet?) - but this is a witness for an individual creative decision. This is for me the point that makes

this individual kilim important. Its beauty is another thing.

Provenance: yes, it means money. But for this reason it must be witnessed and therefore we proposed this A-, B-

and C-Scheme. It cannot be that the only proof is some dealers argot or some story that some Istanbul or Antalya

or Täbriz dealer gave. Because without having got this true provenance you did not identify your weave and

all thoughts like the above given ones are nonsense. Compare it with buying second hand cars. Of course cars without

proper papers (so one can register them anew) are much cheaper - and must be much cheaper because you have to pay

for the expenses to get them registered then.

By the way: the required pictures of McCoy-Jones, pl. 24, and Rageth, pl. 28, will come tomorrow with some helps

of friends (the authors of the German book "Kult Kelim", Harry Koll and Sabine Steinböck)

Regards

Michael

Posted by Steve Price on 05-09-2002 05:46 AM:

Hi Eden,

Thank you for your very thoughtful post. I apologize for the software glitch that left your name off it.

As you point out, "art" means different things to different people. That's why I think it is important

in discussions like this one to be sure we are specific about the kind we're talking about. At least within this

group we all more or less understand what "ethnographic textile art" means and how it is evaluated and

appreciated. Whether workshop rugs are art or are simply decorator fabrics like those that you can buy in K-Mart

really isn't relevant to our topic as long as we remember that they are not of the same genre as ethnographic textiles.

As for modern art, I share your opinion. I look at soup cans and blank canvases and I wonder why anyone bothered

to make them or why the curator in the museum took up space with them. But it isn't a moral issue - I am pretty

comfortable with the notion that something I don't like can be art. I do recall entering an exhibition at the National

Gallery (Washington) and going straight to what I thought was the most interesting painting in the room. It turned

out to be a black door with a brushed steel doorknob.

Steve Price

Posted by Sophia_Gates on 05-09-2002 12:24 PM:

Dear Eden, Michael and Steve, et.al.,

OK - let's agree for the moment just to limit our discussion to tribal art/artifacts.

I am still very uncomfortable with the concept of linking provenance and art. I think provenance CAN provide background

information concerning origins and authenticity concerning a given piece. What it can NEVER do is guarantee that

a piece is beautiful or moving or original or worthy of admiration on esthetic grounds. And yes, Eden, how many

people have coughed up ridiculous sums for old & ugly pieces, or in the modern art world although we're not

really discussing that, for fashionable pieces.

Another problem about tribal art is this: we need to realize that the goals of the tribal artist are often nothing

at all like the goals of the city artist. Navajo sandpaintings, for example, MUST be done in accordance with specific

rules because they are part of healing ceremonies. In this case, creativity and rule-breaking would be very bad

indeed.

Therefore, in order to understand the significance of a work within a tribal group we must understand a lot more

about that culture than most of us presently do! And it's particularly difficult in the case of cultures that have

actually been slowly dying for 150 years or more, because the living members of a particular group - now driving

trucks instead of camels - might have no real clue as to the ancient rituals or meanings associated with very old

work.

Another inherent contradiction: the work we find to be interesting and unusual might be considered to be "bad

art" by the tribal people - as the kilim Michael is discussing - precisely because it breaks certain rules.

We in the modern West, on the other hand, admire creativity and a loose handling of materials, so we find the unusual,

quirky rug admirable.

Does this make sense so far?

My brain has just quit for the time being!

So later, and thanks to all, it's especially nice to hear from a new writer, especially one with so many cogent

ideas.

Sophia

Oh wait - I just remembered something I wanted to say - and it has to do with esthetics: barring any other consideration,

I think esthetics have to be primary at least for me! I would consider spending money on a piece that didn't please

me esthetically, no matter how excellent the provenance, authenticity, so forth, to be a waste of money. But then

I'm not a museum And the converse

is also true: I would most certainly consider spending money on a recent piece if it made me happy.

And the converse

is also true: I would most certainly consider spending money on a recent piece if it made me happy.

I guess that's where the individualism on the part of collectors comes in!

Best,

S

Posted by Steve Price on 05-09-2002 12:56 PM:

Hi Sophia,

I think everyone involved here agrees with your statement, ...

in order to understand the significance of a work within a tribal group we must understand a lot more about that

culture... . It seems self-evident to me that in order

to approach this state, we must know (at the very minimum) which culture and time a piece comes from. Michael argues

that this requires knowing the provenance. I think that overstates it a bit, but I certainly agree that a full

provenance is the best route to knowing when, where and by whom a piece was made. I don't recall Michael or anyone

else suggesting that provenance proves aesthetic quality, although a provenance that includes possession by a distinguished

collector is a sort of expert stamp of approval on a piece.

I would also toss this out (to anyone who cares): much of our discussion focuses on the beauty of a work of art

as the essential element. I think this often - probably usually - misses the intent of the artist who, if he (or

she) is worthy of being called an artist, has much more to offer than just the presentation of an object of beauty.

To cite a few familiar and obvious examples, I don't think anyone sees Kollwitz's primal screams or Picasso's "Guernica"

as beautiful, but they are generally agreed to be important and successful works of art.

Regards,

Steve Price

Note: This thread continues on a second page. Clicking

on the numeral "2" in the lower left part of the page will bring you to it.

Posted by Michael Bischof on 05-09-2002 03:04 PM:

Dear all,

I am contant that things come to be much clearer now. No, I did not mean that provenance has anything to do with

guaranteeing beauty. There is no connection at all. Not all art must be beautiful - Guernica or Kollwitz are striking

examples for that. Our intention was different: to discuss whether something is art or not, beautiful or striking,

kathartic ... one must try to understand artefacts within their context There is no "eternal" self-evidence

of art. And if it would be there the question would come up whether we, coming from an extreme ethnocentric culture,

are in the right position to formulate that.

But kilims and real village rugs represent a not yet studied area where the process of building up measures just

starts. And therefore defining the subject is essential - and this starts with properly assesing the real origin,

especially in the multi-ethnic Near East.

Another problem is, especially for collectors, to differentiate between the meaning some weave might have had in

its contexts and the own phantasies (that originated here, so they have nothing to do with the artefact) and when

"...we find the unusual, quirky rug admirable" this says something about us, but nothing about the weave.

For practical reasons I would guess that to elevate a weave to a textile art study level the following elements

should be there, if possible: proper assessment of its origin ( like with the Pazyryk), knowing

its "fate" ( what has been done with it: how integer is its material structure ?) and studying the socio-cultural

context in which it was made. Then we may start to discuss aesthetical qualities and we may come to the conclusion

that this type of art has something inherent that is equivalent with modern art, for example. - For collectors

all this does not or must not apply. If they are happy with what they have

do not disturb them. Provenance, knowing the "fate" .... more often than not it is better not to know

all details. At least most of the overwhelming feelings after one has got an "occassion" would vaporize

too quick ... at this point of a very fruitful discussion I am ready for a private statement. My personal way to

perceive weaves is this: a great weave is like having been introduced to a great personality, once seen - never

forgotten. A piece that did not have this impact I never counted as being what I would call a top piece of art.

I do not claim, however, that this is anything more than subjective and private, no claim that I would try to enforce

on other people. Its my own measure. And I would be convinced (in the sense of a belief) that in case I would have

the chance, the time, the energy and the money to thoroughly research it adequate material on origin, context etc.

could be found. If not I would have been a fool.

Who knows ?

Regards

Michael

Posted by Eden Ethan on 05-10-2002 04:50 AM:

Hi Michael,

I am beginning to understand your view of provenance by reading through your threads and the latest comments.

If I may add a personal comment, (I am a novice and do not have antique pieces, but if I were to have one) if there

is a piece that you love very much, wouldn't it be only natural that you would want to know more about it, where

it was made, who had it (may not be necessary to be an authority or a well-known collector, this is beside the

point... you are just interested in where the rug had been, what it went through all those years), why was it made

this way .... and lots and lots of questions.... Doesn't that remind you of being in love with someone that you

just had to know every detail of that person, who she was, what was she like when she was 5, who did she hang out

with, what about her family, relatives .... (which might be the root of future conflicts to come, but when you

are in love, who cares!!) ... what I am trying to say is that this provenance thing is actually a sign of one's

passion, love for that piece of rug. (If it is all a part of an academic exercise, than it is a rather sad state

of merely sticking labels like clerks filing documents in the correct folder, in the correct cabinet ... everything

in their correct places ... but I don't think that person will feel the ringing of bells, the quickening of heart

beat when he/she sees a particular document as when perhaps Michael or Sophia would feel when you see something

that clicks and ticks ...)

Again, rumblings from the novice.

Posted by Steve Price on 05-10-2002 06:11 AM:

Hi Eden,

I'm quite sure Michael's statements about the usefulness of knowing a rug's provenance had to do with appreciating

it within its cultural context: you can't do so without really knowing when, where and by whom it was made and

modified.

You mention another reason that, to many collectors (including me) is also important. I find myself driven to learn

everything I possibly can about any piece that I own, and I think you state the underlying psychology very well.

Regards,

Steve Price

Posted by Filiberto Boncompagni on 05-10-2002 06:34 AM:

Dear Eden,

Well, the sentimental-like approach could be en explanation for those people severely bitten by the collector’s

bug.

For more temperate collectors  I prefer to define the desire to know more about the artifact they collect as an intellectual need. Or, if you

prefer, curiosity.

I prefer to define the desire to know more about the artifact they collect as an intellectual need. Or, if you

prefer, curiosity.

The collector is a person who acquires and inquires. Thinking about it, the concept of modern museum was born by

collections built up by individuals or groups before the modern era. The desire to collect objects and data concerning

those objects, to put them in a context and to label them is so old that we can consider it innate in the human

nature.

Regards,

Filiberto

Posted by Michael Bischof on 05-10-2002 07:30 AM:

Hallo all,

let me try to discuss closer at the kilims mentioned here. The kilim pl. 10 , shown above, is in my opinion not

beautiful (refer, if you can, to the picture in "Yayla" by Werner Brüggemann). It is dark, not joyful.

In case the purpose of it would have been to serve as a ground for certain spring time festivities ( admiring fresh

flowers in the open air) it would have been an artistical fiasco. But it is not dark in the sense of dull, matt.

May I propose "secretive" ? A viewer in Germany had said it looks a weave on which humans were sacrificed

- it provokes such an atmosphere. May be a "Kollwitz" kilim in the sense of Steve Price. Art must not

be "beautiful" is my conclusion then.

The original intentions ( why was it once made ?) we do not know. It is an A (-) piece. The picker is known, but

not the single village where it came from, and, of course, its complete

"fate" (what has been done with it later).

When I argue that it is essential to know the origin of a piece to discuss it under the umbrella of "textile

art" this does not mean that provenance has anything to do with beauty or that it is

art because the origin is known.

Let us assume a weave is beautiful but we do not know its origin and its fate. Then I find it difficult or nearly

impossible to rate it as "art" because I have no access to the weavers potential intentions, the purpose

of the weave within its original context ( see above the spring time example) and cannot derive any measures from

that. Whether my own strong

impression of beauty is a misleading phantasy, a strange ethnocentric projection put on something entirely different

I cannot know. For buddha statuettes it would not matter much, as they are researched and as there is independant

science dealing with it. But kilims and village rugs are objects that we start to research and where a lot of common

tools ( like art history) cannot be applied. Mentionable independant research does not exist. - To know its fate

is mainly a commercially important bit of know how: in case it is damaged by amateurish cleaning its value should

be lower, that is all. Some interpretations might fail because certain dyes are dead now and changed , deviating

from their original appearance.

At this moment of a very fruitful discuss I may confess my personal view:

My own, very personal and very subjective approach is that to encounter a great weave is like having been introduced

once to an impressing personality. Once seen - never forgotten.

An artefact that did not match this requirement I would not accept as a "great piece". Unfortunately

one needs some own discipline to differentiate from those pieces that caught the attention for some other reason

( the one piece where the famous gurus did not notice a certain synthetic dye ... the insignificant but perfectly

kept 120 years old Karapinar carpet that the great ........... estimated to be todays production etc). Therefore

the strong feeling of certaincy that this approach produces is easily fooled. Who knows ?

Posted by Steve Price on 05-10-2002 04:27 PM:

Hi People,

Earlier in this thread, Michael said, We often heard

in the fifties such jokes about Picasso. But he was technically well educated

- he did not want to paint like the majority of his contemporary colleagues though he could have done that as well.

With this view pl. 24 of McCoy-Jones is a mishappened kilim and under no perspectives such a thing can be regarded

as art whereas with pl. 28 of Rageth such a discussion would make sense. The prejudice that it is not important

to know the real origin ( and that means: to have, at least theoretical, access to the context in which the weave

was made) of a piece often has

funny consequences. One example for how easy people with this attitude can be fooled - and the ACOR minder is another

example.

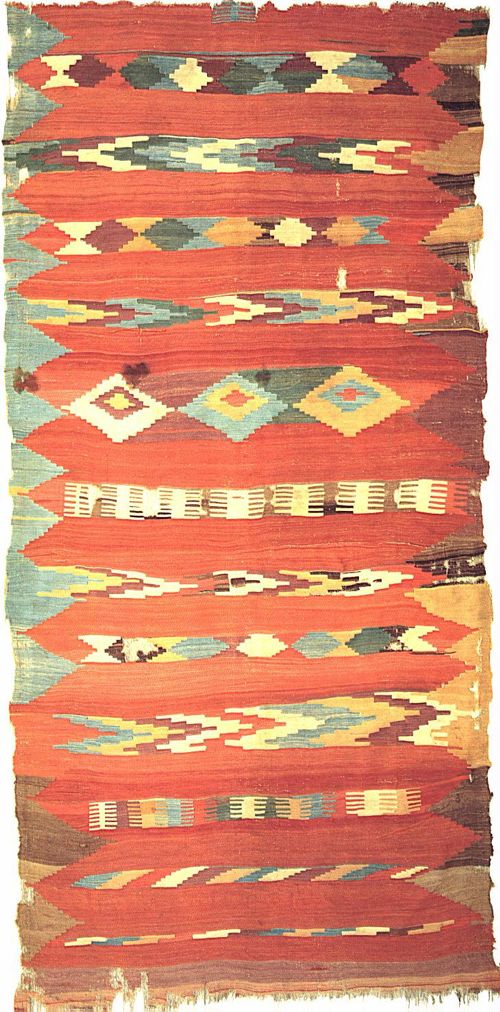

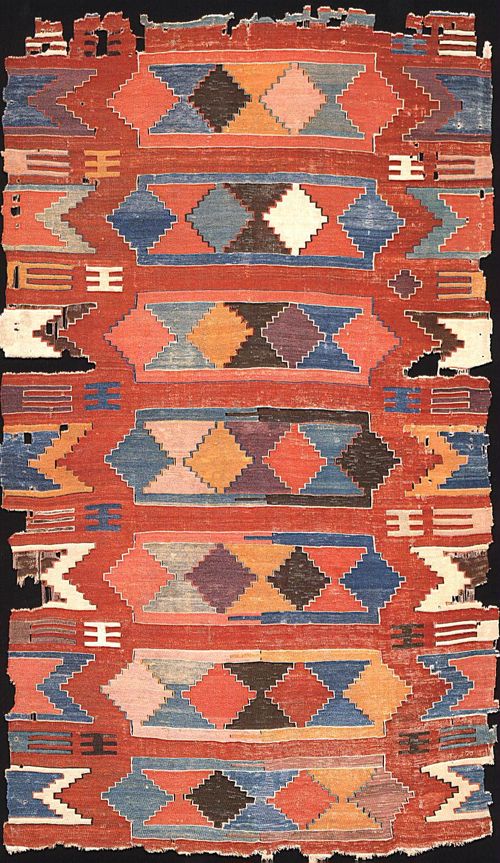

Here are the images of the McCoy-Jones and Rageth kilims, in that order:

They are referenced in a number of subsequent posts, too.

Thanks for sending the images, Michael.

Steve Price

Posted by Michael Bischof on 05-10-2002 05:10 PM:

Hallo all,

thanks goes to Sabine Steinböck, who has written, together with Harry Koll, the book Kult-Kelim and prepared

the exhibition under the same name. After I had made a stupid mistake yesterday she did the scanning twice and

will get one bottle of Regent, the best red wine done in my village, which is kept (in good years only) in barrique

containers. And, of course, to Steve for nice editing the pictures.

Hopefully now with these pictures my point gets clear:

the first kilim is technically mishappened and every weaver will take it like that. I am not at liberty to show

similar pieces from the same origin that are technically correct, have the same yarns, the same weave, which is

considerably coarser than the piece Rageth pl. 24. This piece has a very fine weave ("kagit kilim", paper

kilim), but a similar concept.

Well, for details of the colour one still would better look at the books as digital reproductions are not that

far by now. I hope, though, that once can see that there are obvious washing mistakes with the "smaller"

colours, unusual madder variations. A good colour harmony is obtained when all dyes are close to each other in

saturation. This balance was shifted by washing - but this is obvious only when one gets close to the piece "live"

and has a look "inside" the not that much affected yarns.

Regards

Michael

Posted by Sophia_Gates on 05-11-2002 12:37 PM:

McCoy-Jones/Rageth

First, a note to Eden:

Of course one wants to know as much as possible about the treasures one collects! But isn't that true of any art?

One of the primary purposes of art is to bring people together regardless of time & space. But I have to agree

with Rudolf, in the case of tribal weavings provenance is going to be difficult if not impossible to derive and

I still agree with myself - is

no guarantee or barrier to the artfulness of a piece - that is part of the piece, not of the owners!

- is

no guarantee or barrier to the artfulness of a piece - that is part of the piece, not of the owners!

Note to Steve et. al. - of COURSE art can/should be more than beautiful. By esthetics, that's what I mean - esthetic

satisfaction comes from ALL the tools of the artist working together, to create a spiritual dimension as well as

appearance. I think I've argued this frequently here. Never mind! Doesn't hurt to repeat it. However, if you'll

forgive me, the last thing I need around here is a fuzzy Guernica

Finally - on to the McCoy Jones & Rageth kilims: I agree, I like the Rageth kilim much more. BUT - not because

the one is misshapen - but because the other is vastly superior in terms of form. The color is better, the contrast

is better, there is a broader range of values, the chromatic constrast (brightness/dullness) is more subtle and

more effective. So, the Rageth kilim is a more successful design all 'round. The least of the McCoy Jones' kilim's

problems is being out of shape!

So here you have a situation where poor craft is being blamed for unsuccessful design - and they're not the same

thing at all! This is why I really think people who are involved in the art world should study art - not just art

history but actual design, really learn what makes a piece work and another one, not. A college-level basic design

course would be a good starting point.

Posted by Sophia_Gates on 05-11-2002 12:43 PM:

P.S.

Not to say I don't like the McCoy Jones kilim too - I do, and

I think if somebody wants to give it to me I could find a spot for it

But I think the Rageth kilim has an immediacy, a punchiness to the design, which is very strong.

To elaborate a bit on the art/craft thing: the management of values (lightness/darkness), colors, shapes, etc.

isn't a matter of merely being expert at handling the craft of weaving. It's a matter of the mental exercise, the

intellectual aspect of art-making, which can be very calculated or remain on the intuitive level - either way it

requires talent and ability. How good a weaver is at managing her wool is another aspect of the art altogether

- it certainly helps, but if she lacks the imaginative ability, the color sense, it's not going to save her work

from mediocrity.

Make sense?

Thanks to all,

Sophia

Posted by Michael Bischof on 05-11-2002 01:35 PM:

Hallo all,

yes, Sophia, it makes sense ! Leave aside that the wool of the Rageth pl. 24 - piece is much finer and much more

thoroughly dyed. This kilim appeared later and was exhibited later. We talk about restauration here, including

washing. Forgive me to refer to observations that one cannot transport using digital photos. Now imagine the "minor"

colours in this peace would have a similar saturation like the main dyes ! This would be kind of original status

and the aspect that this kilim must have had when it was taken from the loom. Therefore this would reflect the

original intention of the weaver the best.

Today we need a lot of "mind painting" to imagine how it must have been looked like ... and improper

washing enlarged the problem to quite some extent.

The physical pleasure of viewing dyes goes down from that.

But our intention here was a bit different: when the McCoy-Jones kilim was shown a lot of people who had this "instant"

access to art admired it a lot, it was one the shows favourites. But this was an artefact ( an artificially created

event) by itself. Because the origin was not known and the people did not want to imply the context of this weave

( as far as one can study it today - and one can) they did not like to notice that this piece was mishappened,

no great bold art, simple something that did not happen successful.

In the Essen catalogue there are two splendid examples of early "bold" kilims where one would never say

it is looking a bit "primitive" because the weaver could not do it technically better. They are bold

because the imagination of the picture was bold in her brains !

I refer to plates 15 and 16 in the Essen catalogue.

Therefore we stressed here to know the origin ("provenance") and to try to understand the original context

of this weave. The alternative would be a kind of unlimited ethnocentrism.

Regards

Michael

All times are GMT -5 hours. The time now is 12:53 PM.

Powered by: vBulletin Version 2.2.1

Copyright © Jelsoft Enterprises Limited 2000, 2001.