Posted by Yon Bard on 02-03-2002 09:36 AM:

crosses etc.

Finding a cross on a rug makes it no more Christian than finding

a swastika makes it Nazi. Even the Pazyryk (400BC) has a well-defined cross within each square on its main field.

As for Marco Polo, he says that they had the most beautiful rugs in Central Asia. Of course we have no idea who

made them, and there is some reasonable doubt on whether he had ever been to any of the places he claims.

This does not relate to Caucasian rugs specifically, but I will in a day or two make an append strongly supporting

the theories that trace rug motifs back far into prehistoric times.

Regards, Yon

Posted by Sophia Gates on 02-03-2002 02:31 PM:

Ancient Motifs

Jon raises some excellent points. I know I'll look forward to

seeing his additional comments.

My friend Jane says she thinks certain symbols are essentially hard-wired into our brains, and that we will respond

to them - as humans - regardless of what layers of meaning have been attached to them culturally. I believe this

is similar to the Jungian concept of "collective subconscious".

Certainly the cross is one of those primary symbols. It's so emblematic of weaving, for one thing, that to the

Dineh - the Navajo - it's the very symbol of Spider Woman. But beyond that, it's one of those essential, basic

forms that relate to our perceptions: sun, star, human with arms outstretched. So of course it wasn't always -

isn't always - attached to the Christian belief. In fact I suspect it might have been the other way around - that

the symbol was so well recognized and so powerful that the new religion adopted it to carry their own ideology.

Be that as it may, I think Grantzhorn is trying to make a point - which he might overstate a bit - that the Armenian Christians may have had something to do with

pile rug weaving and its design. Weren't they quite active in the Caucasus? I think it's something to consider.

- that the Armenian Christians may have had something to do with

pile rug weaving and its design. Weren't they quite active in the Caucasus? I think it's something to consider.

As far as Marco Polo goes - he's certainly a primary source and we can probably take his word for it that beautiful

carpets were woven in Central Asia. But by whom? I've always taken it for granted, as a lover of Turkmen weaving,

that the horse-mounted nomads were responsible for these beautiful things. But lately I've been wondering - based

on my studies of other nomadic cultures - if they would have had the time, energy or resources, to make finely

woven pile carpets? My dad who of course Knows Everything, commented to me once that the Mongol horsemen essentially

had no artistic culture of their own, although they fostered it in others when they came into power. So I wonder

- are the beautiful pile weavings that have come down to us actually the descendants of nomadic art, or were they

actually created - possibly by sedentary Turkmen - possibly by other groups - in the cities and towns of Central

Asia?

Posted by Michael Wendorf on 02-03-2002 03:03 PM:

Marco Polo

Dear Sophia:

With regard to Marco Polo, the point is actually the opposite. He is not necessarily a primary source and you cannot

"take his word" for anything. It is very likely that Polo never traveled to many or perhaps any of the

places he wrote about. We really do not know and the matter is one that remains very open to question. Even, if

he did travel, it would be a great leap of faith take his word on much at all. Only if it were that easy.

Regards, Michael Wendorf

Posted by Yon Bard on 02-03-2002 04:00 PM:

Sophia, I think that doubting the ability of pastoral nomads

to produce pile carpets is carrying deconstruction to extremes. Vambery in the 1860s observed Yomud women weaving

carpets. In our own days Mike Tschebull has reported seeing Shahsavan nomads weaving rugs in Persiuan Azarbayjan.

There are photographs of Turkoman weavings in use by the tribespeople, and there are tentbands and asmalyks depicting

wedding processions. The size of the typical Turkmen 'main carpet' is right for people who do not live in houses.

It is true that some authorities (e.g., George O'Bannon) have bandied about the idea that the most elaborate nomadic

weavings such as the Salor had to be made by settled people, but there has been no proof of that. Mike Tschebull

has also made the point that really poor people cannot afford to be pastoral nomads, and it can be argued (truthfully,

I believe) that the women in a nomadic population have more leisure time to engage in weaving, than members of

a sedentary population who are endlessly engaged in agricultural chores. It is true that the Mongols appear to

have no weaving tradition, but it is a remarkable fact that the Turkic people do weave wherever they have settled,

all the way from the Uighurs of Sinkiang to the 'Turks' of Turkey.

Regards, Yon

Posted by Sophia Gates on 02-03-2002 05:05 PM:

Dear Jon:

I agree it's kind of deconstructivist !

- and also with your assertions that we can see Turkmen in modern times weaving, etc. But what I'm curious about

- is way back when - and the very point you make about the Mongols not having a weaving culture, yet Turkic people

everywhere, once they settle, weave.

!

- and also with your assertions that we can see Turkmen in modern times weaving, etc. But what I'm curious about

- is way back when - and the very point you make about the Mongols not having a weaving culture, yet Turkic people

everywhere, once they settle, weave.

Is it possible that they learn from settled neighbors? Can they adopt a weaving culture that quickly?

I would say, looking at the Navajo as an example, that people with no weaving culture can become so expert at it,

within a very few years, that their weaving is regarded as exemplary. The Navajo were an example of a nomadic,

hunter-gatherer group who picked up weaving from the Pueblo people and also from the Hispanic settlers in the Southwest.

They learned from being slaves (to the Hispanic) and from taking them (from the Pueblos - where weaving is men's

work and is done in the sacred kivas - it seems to be tied into their religion and is indeed an ancient craft).

It is tempting, looking at the marvelous Navajo work, to assume that they've been doing it for many centuries but

that is simply not the case. Some of their designs have an ancient origin, for example the "yei" and

"sandpainting" rugs, which originally were copied - with much trepidation, from images used in healing

ceremonies. The first of these were made, I believe, in the early 20th century. Commerce was the direct motivation.

An important point: the rugs do not convey the power of the drawings, which traditionally are destroyed during

and after the ceremonies. In this sense they differ from the Berber pieces mentioned in the Salon dissertation.

Other sources for Navajo designs were of course what they picked up from their Pueblo neighbors (and victims!)

and the Hispanic serape and stripe designs, which in turn had both Oriental and native origins. Still others were

directly derived from Turkish and other Oriental designs shown to the Navajo weavers by white traders. Another

interesting point, I think: Pendleton Mills started trading blankets to the Navajo, machine made "Indian Blankets",

which they began using to wear in the late 19th century - and their own blankets became an important source of

income for the defeated tribes, who had to give up their wandering ways and settle on the reservation at last and

raise sheep - courtesy both of the US Army and of the long-suffering Pueblo, who had very nearly been wiped out

by the marauding nomads.

Now the Dineh are the largest and most successful of the Native American tribes in the US. Their adopted skills

as sheepherders and weavers - and jewelers, another craft they learned, primarily from Mexican silversmiths - have

stood them well.

Notwithstanding that it is dangerous to draw direct parallels, is it possible the Turkmen went through a similar

process of transformation?

Posted by Yon Bard on 02-03-2002 06:15 PM:

I have never claimed that the Turkomans or any other nomads

invented weaving pile rugs, so I would not be surprised if they went through processes similar to the Navajo. I

just object to claims that the nomads don't weave at all. As for the origins of their motifs, they range from motifs

found in other media since antiquity to motifs found on rugs of neighboring people, and I am sure that applies

to almost any weaving culture - including the Navajo, who make both rugs resembling orientals which they copied

from the Europeans, and rugs based on traditional Navajo sand-drawing motifs such as the Yei figures.

Regards, Yon

Posted by Steve Price on 02-04-2002 06:34 AM:

Hi Sophia,

In a post above this one, you wrote, "My friend ... thinks certain symbols are essentially hard-wired into

our brains ... we will respond to them ... Certainly the cross is one of those primary symbols."

There is no doubt that certain forms are hardwired into our brains as things to which we pay attention. The best

known is probably faces, which require only minimal features to be seen as such. The point at which a form becomes

perceived as a symbol - especially a symbol to which we respond emotionally - is not easy to define, though, and

I am unaware of any evidence that a cross is a "primary symbol" in the same sense that a pair of simple

closed figures symbolize eyes and, by extension, a face.

The simple explanation for the ubiquitous occurrence of crossing lines (a term less likely to conjure up cultural

associations than "cross") is that it's almost impossible to NOT make a lot of them if you are decorating

an object with forms of any kind, especially if the method you are using precludes smooth curves.

As for how long it would take a culture to become pretty good at doing something they had never done before, I'd

think a generation or two would suffice if the right people came along to discover and disseminate the skills.

In the grand scheme of things, that's a very short time; surely not more than 50 years, probably less than 35 years.

Within the context of oriental rugs, after all, date attribution is rarely more accurate than nearest 25 to 50

years.

Regards,

Steve Price

Posted by Filiberto Boncompagni on 02-04-2002 09:52 AM:

Dear All,

Well well, I see some people dare to doubt of Messer Marco Polo’s words!

You are not the first ones. From the very beginning, his chronicle was met with a lot of skepticism… A little quotation

is now de rigueur:

Modern scholarship and research have, however, given

a new depth and scope to his work. It is now generally conceded that he reported faithfully what he saw and heard,

even though much of what he heard was fabulous or distorted. (Encyclopaedia Britannica, 1999)

I read that Marco Polo’s book is of great value to Chinese historians, as it helps them understand better some

important events of the 13th century not well covered by extant Chinese sources on these events.

His system of measuring distances by days' journey has turned out to be remarkably accurate.

On the other end he did not mention a lot of things, such as the Great Wall of China or the use of tea, for example,

so we have to take him more for what he says than for what he doesn’t (hope this phrase is correct  ).

).

There are some 140 different manuscript versions of "Il Milione". The Franco-Italian text quoted by Gantzhorn

seems to be the more reliable and it is not too different from an other text in early Italian to which I have access.

In both texts the phrasing is such to suggest that the "most beautiful carpets" from "Turkmenia"

(North Caucasus under Mongolian domination) where actually made in cities, not in the countryside. The cities were

inhabited by "Armenians, Greeks and Muslims."

But let’s forget Marco Polo and consider a little bit Gantzhorn. I agree with Sophia on the fact that he made a

good case in finding historical resources showing the Armenians had a long weaving tradition. Unfortunately he

exaggerates when:

1) he tries to demonstrate the Armenian-only origin of pile rugs

2) in seeing every cross design on rugs as a Christian-Armenian heritage.

Gantzhorn also proposes that Turkomans didn't weave pile rugs… I’m going to discuss that in an other posting.

Regards,

Filiberto

Posted by Steve Price on 02-04-2002 10:54 AM:

Marco Polo

Hi Filiberto,

I read this in your post: Modern scholarship and research

have, however, given a new depth and scope to his work. It is now generally conceded that he reported faithfully

what he saw and heard, even though much of what he heard was fabulous or distorted. (Encyclopaedia Britannica,

1999)

From the standpoint of someone looking for reliable sources of information, what difference does it make whether

Marco reported faithfully what he saw and heard if much of what he heard was fabulous or distorted? It was asserted

somewhere in this discussion that he is a primary source of information. In fact, he is a source of misinformation.

This is independent of whether he created that misinformation or simply repeats misinformation that he got from

others.

I am baffled by Encyclopedia Britannica considering his "work" to have depth and scope when they know

that much of it is fable or distortion.

Regards,

Steve Price

Posted by Yon Bard on 02-04-2002 11:28 AM:

For me, the most disturbing thing about Marco Polo is that (as

far as I know) there is no mention of him in any contemporary Chinese sources, even though he claims to have been

an important functionary in the Emperor's service.

Regards, Yon

Posted by Filiberto Boncompagni on 02-04-2002 11:54 AM:

DearYon,

This quotation is for you:

On the other hand, more sober critics point out that

contemporary Chinese records show no trace of Marco. (But under what name was he known: who would recognize the

16th- and 17th-century Italian missionary Matteo Ricci under Li Matou or the 18th-century painter Giuseppe Castiglione

under Lang Shih-ning?) (Enciclopaedia Britannica 1999)

Steve,

You have to put it in context with the time he wrote it, the medieval ideas of the world and the fact that an original

copy of the book does not exist. There are 140 versions, every one with variations: professional scribes or amateurs

made dozens of copies of the book, as well as free translations and adaptations. The printing did not exist yet.

Still it seems that philological analysis found that most of the facts described are true and - again - he reported

faithfully what he SAW. Besides the wealth of new geographical

information recorded by Marco Polo was widely used in the late 15th and the 16th centuries, during the age of the

great European ocean voyages. (Enc. Brit. 1999) Anyway,

if you mean that Marco Polo is not a valuable source of information concerning rugs I can only agree.

Now, to go to an other topic:

"As for how long it would take a culture to become pretty good at doing something they had never done before"

I think I have a good example:

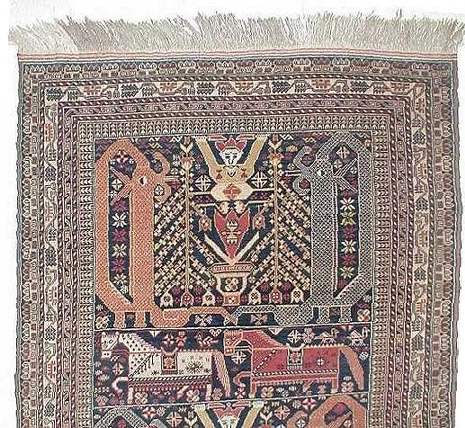

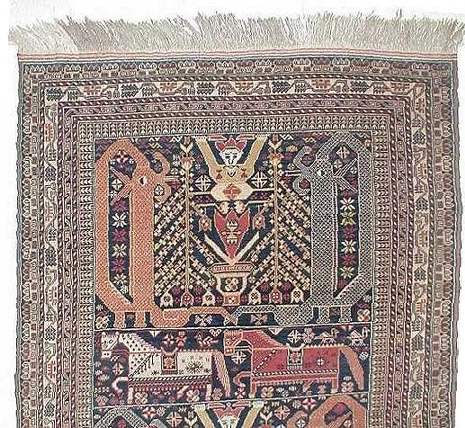

We received this rug as a present some 8 years ago:

It was new and they told us it was Afghan. I didn’t like it at first - it is not the sort of colors I like in rugs

- but with time I get accustomed to it. Good wool, very fine weaving, very good craftsmanship. In these few years

the carpet improved a little, so it is a real one, not a "carpetoid" as Michel Bischof would say.

From Parsons’ "The Carpets of Afghanistan" it matches the palette of the Tchitchaktu Production".

According to Parsons these rugs are (or were- don’t know what is going on now) woven by Pasthun tribes who learned

recently to weave knotted piles from few Turkomans living in the area. The "Tchitchaktu rugs" appeared

first in the summer of 1971.

You may not like it, but it shows a great maturity in spite of its lack of tradition.

Regards,

Filiberto