The forms these artists chose express volumes.

So I’ll try to keep the chatter to a minimum.

Let’s start in ancient Greece, at the dawn of the Classical Era:

The Charioteer of Delphi stands, full of confidence, draped with classical restraint. He is calm, fearless, a specific man gazing out at his world. He finds himself, in his youth, holding the reins. He is equal to all he sees, from the top of his magnificent head

To his splendidly articulated feet.

This young one lived before the full flower of Athens. He avoided the Peloponnesian Wars that brought about the collapse of classical Greece. He never saw the wars with Persia or the invasions of Alexander. He stands at the beginning of an arc, an arc of Mediterranean history that would culminate in the manifestation of one god

and the birth of another.

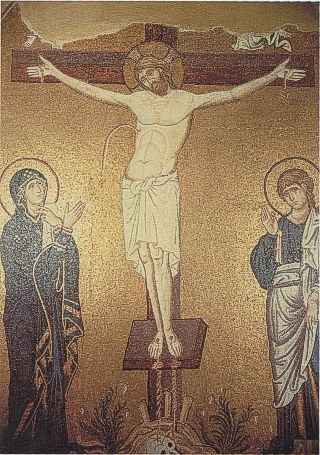

At her peak, Rome controlled much of the known world. In the east, her soldiers could sometimes wave at the soldiers guarding the outposts of China. In the north, Britain became a colony, all the way to Hadrian’s Wall. To the west, she controlled Iberia, to the south – the entire Mediterranean world. But when on the eve of battle, Constantine accepted the flaming signal of the Chi and Ro in the sky, a cross-shaped flaming icon; Christianity gained the status and power of a state-sponsored religion. Rome fell in the west and in the world of Byzantium the old, proud forms dissolved in a field of gold.

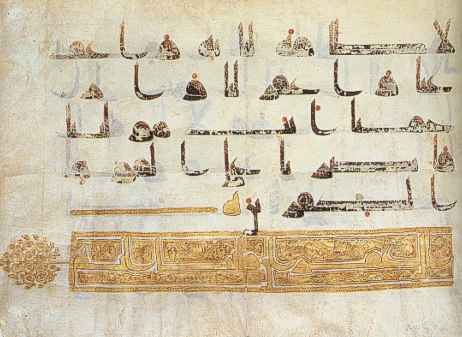

Not long after, the flags of Islam would surge outward from Arabia and bring a new faith – and a wonderful new way of seeing the world – the outward expression of geometry. Beauty was found in the expression of pure mathematics, faith in the glory of a tolerant and open way of life.

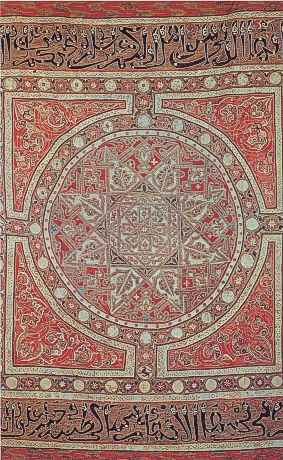

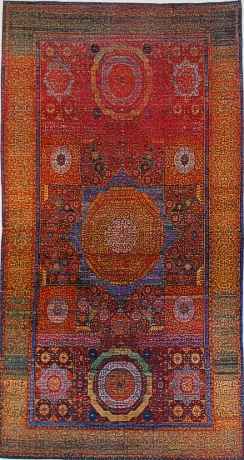

Here’s a silk banner from Muslim Spain, dating to the first half of the 13th century.

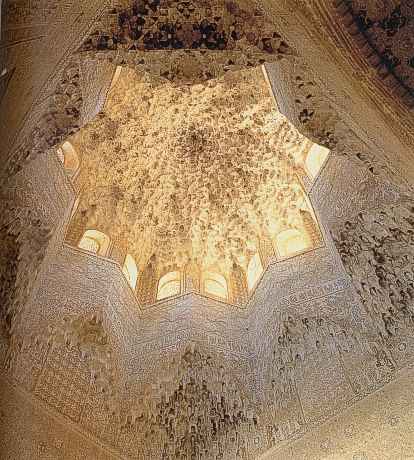

And here is the interior of the dome from the Palacio de los Leones, completed in 1380.

Light floods down from above, blessing the works of man.

As he gazes upward, his vision dissolves in a golden star.

We often speak of the Dark Ages in Europe, after Rome fell and Islam rose. But it’s hard to look at beauty like this and see darkness:

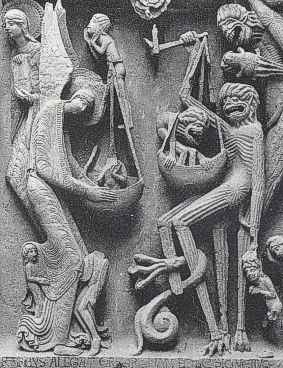

Here is the Last Judgment, typanium of the west portal, Cathedral of Saint-Lazare, Autun, circa 1120-1136. This is a glorious example of Gothic art, magnificently carved and full of expression. But it reflects an entirely different view of man and his world than that expressed by the young Charioteer of Delphi. Man is small and weak; god is large, all-powerful. Here’s another detail, showing the weighing of souls:

And another carving from the same cathedral, showing The Magi Asleep:

However, during this time, scientific inquiry in the west linked to spiritual ideas, to concepts that reflected the Christian faith. Cathedrals were built that soared like stone songs, and took sometimes more than two centuries to complete. Can you imagine, working a lifetime on a building you’d never see finished, that your children wouldn’t see finished, or theirs?

And the artists of the Gothic world sang aloud their faith, through hunger, warfare, plague and strife.

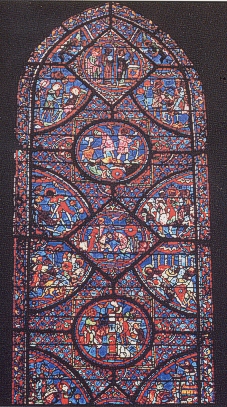

Look at this stained glass window from Chartres Cathedral, 1210-36

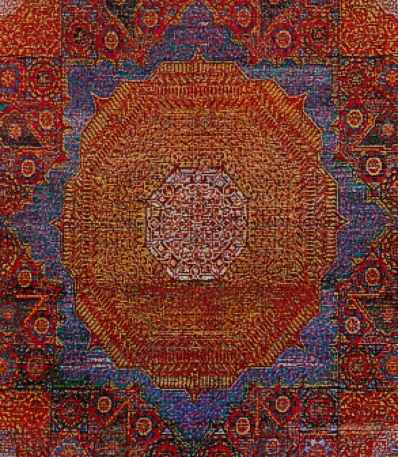

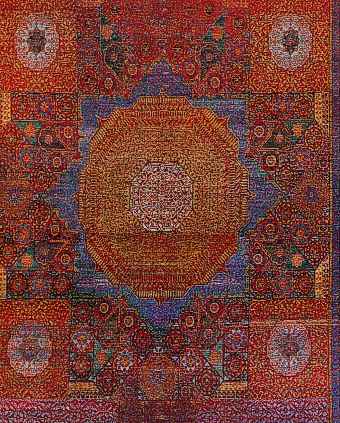

And look at this carpet from the world of Islamic art.

How expressive these works are in their use of color, and their magical transformation of geometric forms into art. These pieces are from different worlds, different centuries, and created in different media. Yet – aren’t they similar, in their flat abstraction, their geometric layout, their brilliant use of color?

Here’s a late Gothic piece from Siena, early 15th century:

Note the figures; they are beginning to acquire some form, some roundness. Yet, they remain somewhat stylized and linear.

And look at the richness of the detail, the love of Oriental fabrics.

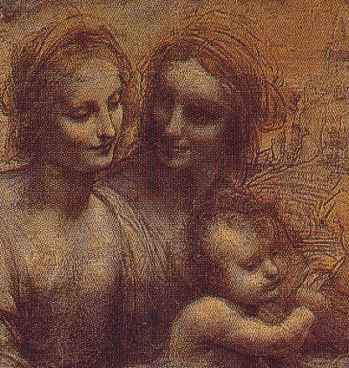

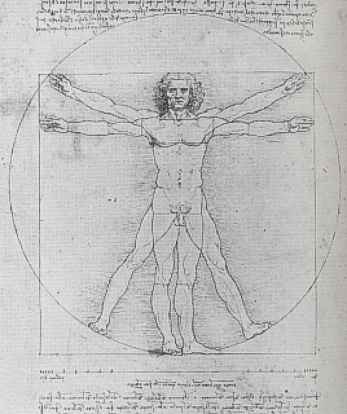

The process of the Renaissance was just beginning in Europe, a process of rebirth that would cause artists to begin looking at nature again, and scientists as well. Here is some work by Leonardo da Vinci, a man of both art and science.

The painting with the four figures has a religious theme, The Virgin and St. Anne with the Christ Child and The Young St. John the Baptist – 1500-01 - but look at the modeling, the way Leonardo has used light to reveal form, naturalistic form. And here, he makes an attempt to link man with the very geometry underlying the ways of the universe (Vitruvian Man, 1490):

Ultimately, the Renaissance would change the way people thought, the way they saw, the way they felt about their position in the universe.

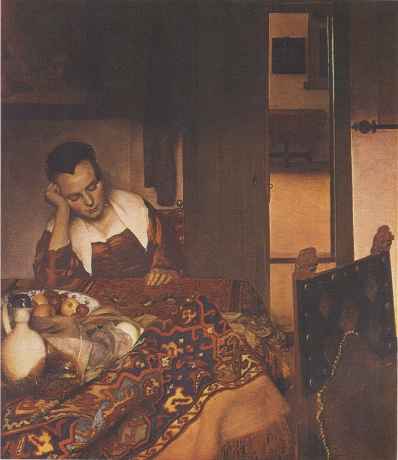

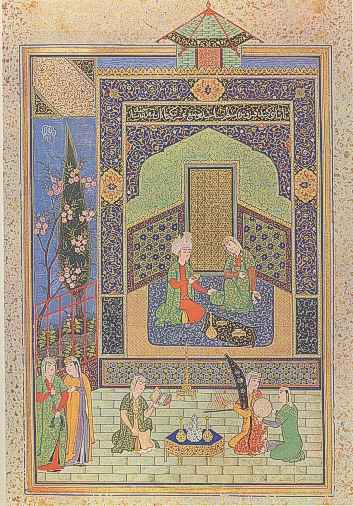

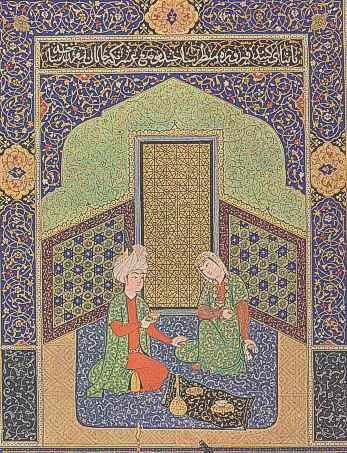

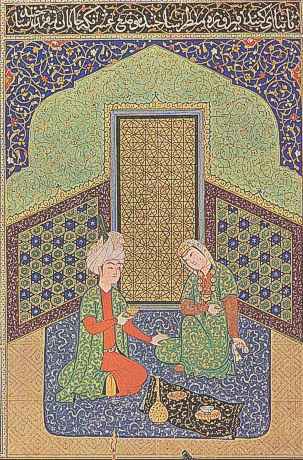

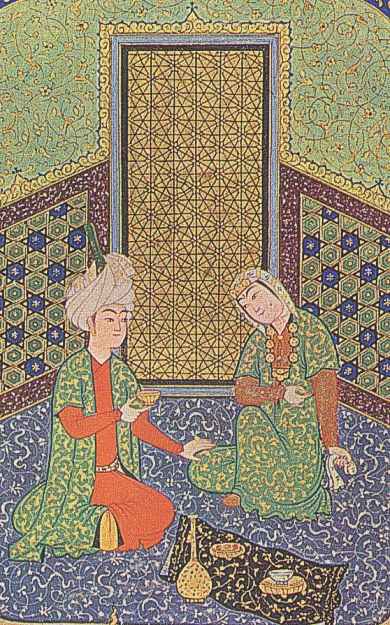

This is Vermeer’s Girl Asleep, 1656. And here we have a Persian miniature, Bahram Gur in the Turquoise Palace on Wednesday, 16th century Herat school:

Compare the way of seeing, the expression, the FORM, of this piece, with the Vermeer above. You’ll see these worlds were well aware of one another – look at that beautiful carpet in the Vermeer! – but had an entirely different world-view. The one is down-to-earth – the serving girl is asleep, perhaps even drunk! And her surroundings are plain, expressed in a clear manner using the contrast of dark and light. The Persian piece depicts an idealized world, an expression too of the wonders of geometric and curvilinear pattern rather than capturing three-dimensional form in a naturalistic setting.

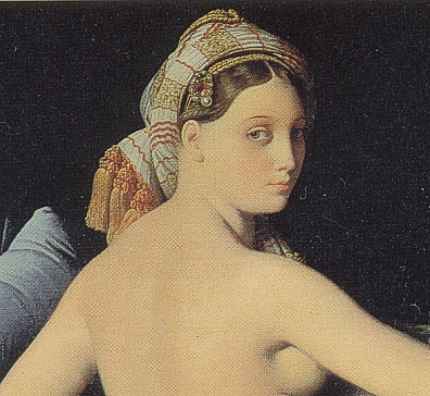

In the west, we’ve mentioned the French Revolution and the artists of the Neo-Classical movement. After the excesses of the French Monarchy, they were eager to re-establish an esthetic based on the clarity of thought and form and Republican ideals exemplified by the Greeks, even more by the ancient Romans. Yet look at this fabulous piece by Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres, perhaps the most accomplished of all the Neo-Classical painters:

Oddly enough, like his Romantic contemporary (and enemy!) Delacroix, Ingres was fascinated by the Orient, and by the ideal of Oriental woman. Both loved the image of the Sultan’s passive and gorgeous mistress, existing only to serve her master. And both were rebelling against the sharp-tongued women of Paris, who were demanding their equality!

In this image of luxe, calme & volupte, a tired man could find peace.

But the stranglehold of French neoclassical and academic art and the dreamy, rather tired ideals they exemplified couldn’t hold off the energy of the modern world for long.

First came the Impressionists, then wave after wave of painters exploring the visual world, captivated by the color, the true colors of light, the dance of light on water, the dissolution of the old forms into a flood of color.

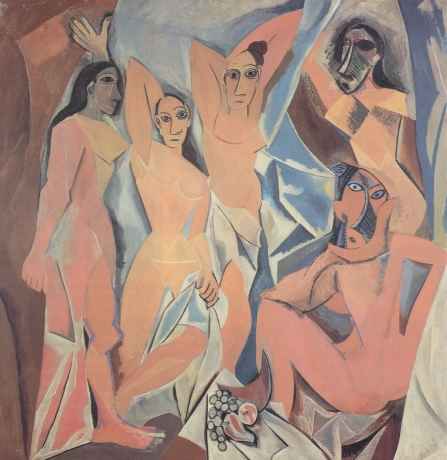

By the time Picasso came into his own, the Industrial Revolution had been in full swing for a century, transforming the world and its economic structures and threatening to overwhelm the existing order altogether. A hungry young painter in the Paris of 1900, he was one of the most gifted classical draftsmen, perhaps, who’s ever lived. But as he looked around him, as he dug deep within himself to find a way of expressing what he felt, he came up empty and discouraged. Beautiful work he could make, even innovative and expressive work – but still it left him feeling as though he couldn’t get a handle on what he was seeing, what he was feeling. Finally, in 1906, the Louvre put on an exhibition of Iberian sculpture. It has widely been thought that Picasso’s Great Idea came from African sculpture, and I believe that is also true. However, the more direct link appears to have been these ancient figures that not only came from his own homeland but dated to the 5th –6th century B.C. And, he was influenced by Gauguins paintings, many of which reflected the esthetics of “primitive” art and “primitive” people.

And so, this gifted, classically oriented painter, trying to express the Brave New World around him, went back to the ancients!

This painting broke the floodgates. It took form and stood it on its head. All the careful rendering, the observation from life, the beauty of the Impressionists – destroyed with a stroke of the brush!

People were horrified! The other artists, though – said – YES. This is modern, this is new, this says what I want to say.

Umberto Boccione, States of Mind: The Farewells, 1911.

We’ve discussed Caucasian rugs, going all the way back to the Sycthians. We’ve talked about religion, we’ve talked about Persia; dragons have flown and blossoms have blossomed. But we haven’t discussed the advent of the Industrial Revolution on the world of Central Asia, except perhaps to lament the presence of synthetic dyes!

Perhaps we’ve been overlooking something? Perhaps these weavers, after all their long history, were no less affected than Picasso by the Brave New World they sensed coming upon them.

Did they forget how to make art? Did they become clumsy, less gifted? Did their forms degenerate from older, fancier ones? Or did they burst their bonds, explode with a new exuberance of joy and terror, with a new vision of a new world before them?

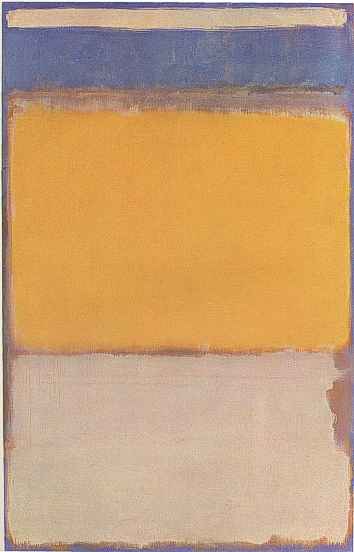

Mark Rothko, Number 10, 1950.