Posted by Elise Sophia Gates on 02-05-2002 08:48 AM:

Design Derivation – Or?

The question has arisen, concerning the derivation of certain

motifs from earlier, possibly more sophisticated design sources. In some cases, I think it is fair to theorize,

as Ms. Close has done and as Michael Wendorf has asserted in the Lancet Leaf/Dragon discussion thread. But – as

others, including Pat Weiler, have pointed out, the problem with their assertions is that they do not take into

account the possibility of pure inspiration on the part of an artist; they can’t prove the “chain of evidence”

from one source group to another; and they certainly can’t account for all such instances of apparently similar

appearance over great spans of time or space.

In fact, in these latter cases attempts to prove connections can be outright misleading. I’ve prepared some scans

from various sources, with which I’ll attempt to illustrate my case.

Here we see a couple of animals, with horns, remarkably similar in appearance to these:

Can we assume a connection or even a design derivation from one textile to the other? It would appear that the

top textile shows animals in a somewhat simpler form than those on the lower piece; perhaps this is a case of one

artist copying or taking inspiration from another?

Well – maybe. But as it happens, the bottom piece is a Caucasian cover illustrated on page 31 of Wright and Wertime’s

Caucasian Carpets and Covers, a fairly typical example of this sort of animal imagery. The other, however,

is an American piece from Peru. It appears to be depicting llamas marching in procession – yet it’s so striking

how similar it is to the Caucasian piece, even down to the depiction of a smaller animal atop a larger, and the

formation of a sort of “dragon” s-form created by the juxtaposition of the two animals – recalling Caucasian Dragon

silehs - that we are tempted to find a link where one might not in fact exist. And before we go jumping off the

deep end and assert that of course the Peruvian weaver might have seen a Caucasian piece in a book and copied it

– let us recall that South American textile culture is truly ancient, and we may be dealing here with two completely

different strains of artistic endeavor that managed, through observation of real animals combined with a certain

“primitive” type of stylization, to come up with a very similar design.

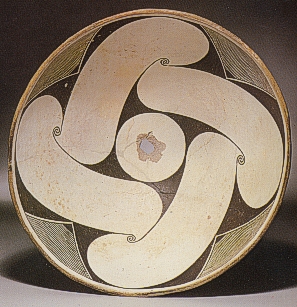

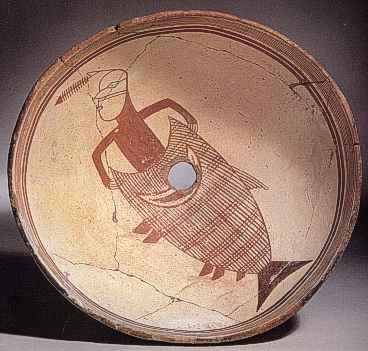

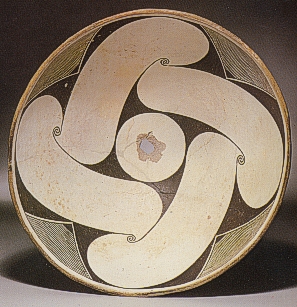

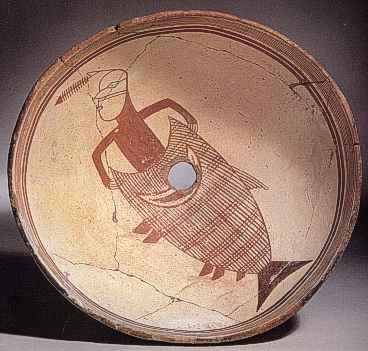

Here are some other examples:

These textiles are obviously Turkoman ashik – or leaf – designs. We’ve gotten so used to seeing them we hardly

question their origins. Yet here we have, in the photo below, a painted version of this design that predates them

by hundreds of years.

So – are we to assume this ancient painted ceramic is a precursor to the Turkoman weavings?

Well – considering that this design was painted in the Mimbres Valley region of the prehistoric American Southwest

– probably not! Although I’ve read some theories that Turkoman horsepeople could have sailed the briney deep –

I think this is another case of genuine coincidence. Or, to look at it through Jungian eyes, this is one of those

designs so ancient – a stepped diamond – particularly surrounding a central “eye” form – that it resides in the

collective subconscious memory of us all. It is part of our HUMAN design heritage, and belongs to no one group

and to no particular time.

Incidentally, the Mimbres were superb artists, whose paintings on pottery must rank among the highest of artistic

achievements. Yet they started painting only about CE 650 and by 1050 their art had reached its pinnacle in the

Classic Black on White, Style III pottery. This coincided with an increasing scarcity of food in their valley and

by 1150 or thereabouts, their culture collapsed. Nobody knows what became of the Mimbres people. Their valley was

simply abandoned.

In conclusion, I think it is dangerous to make assumptions about design derivation based upon appearances. We must

remember that artists look at nature, not just at other art; and, they look inward, into their own hearts and psyches,

for inspiration.

Nota bene: these are funerary bowls. The damage is caused

by the artist making “kill holes” in the center. Some people say this is to free the spirit of the artist, akin

to the spirit lines in Navajo rugs; I’ve also heard it’s to “kill” the power, the magic, in the bowl before burying

it. This would be similar to the destruction of sandpaintings, I think.

Sophia Gates

Posted by Steve Price on 02-05-2002 09:17 AM:

Hi Sophia,

These images make great food for thought.

First, the Caucasian and American birds. They DO look a lot alike, almost disturbingly so. But notice this: in

each case the motif consists entirely of horizontal lines, vertical lines, and lines at a 45 degree angle to the

right or left. I spent a few minutes trying to generate bird images using the constraint that they had to be made

entirely of such lines. Guess what they look like? There's little you can do to avoid making birds that look this

way with the techniques these people used.

It's interesting to see that when using a medium in which curves are possible, as in pottery decoration, birds

don't look a bit like those. Your Mimbres pottery illustrates this very nicely. I know, I know, the Mimbres critter

isn't a bird, it's a bat. But it's unlikely that this distinction made a difference to anyone in a low-tech society.

A bat was just another flying animal, a bird that flew at night instead of by day.

As a point in passing: some Andean textiles include what looks for all the world like a boteh.

Regards,

Steve Price

Posted by Filiberto Boncompagni on 02-05-2002 11:54 AM:

Dear Sophia,

Well done!

Connections are misleading as you demonstrated above.

My opinion of why the Turkman ashik and the design on the Mimbres bowl are so similar is that Mimbres created it

on a flat weave first. As Marla says some designs are the product of technical restriction in the weaving medium

and this is one of them. The design was attractive and was reproduced on the bowl. The original textile(s) disappeared

but the bowl survived.

Incidentally this shows that the efforts of people like Gantzhorn and - why not? - Elena Tsareva to find a one

and only ethnic origin of rug weaving on the basis of certain common archetypal motifs is to take with a pinch

of salt, don’t you think?

Regards,

Filiberto

Posted by Sophia Gates on 02-05-2002 12:07 PM:

Birds and Bats

Steve:

I think you make an excellent point about the similarity between the designs on the two textiles. Given the technique

used to make them, they are bound to look similar. However, I think the point is still valid: we can't make linkages

based upon appearance alone, no matter how tempting it might be!

I must take exception, however, to your comment that birds & bats were just your basic flying critters, to

low-tech societies.

Steve, that just isn't so! These are cultures that were extremely "hi-tech" when it came to nature. They

were intimately acquainted with the creatures in their world, with their habits, whether they could be eaten or

if they'd eat you. And they had very specific symbol-languages and mythologies attached to them - some of them

were religious figures. The bat in particular is a "loaded image" - again, there's a connection with

China: whereas bats in Western culture as seen as dark, evil, bloodsucking creatures from Satan, the Chinese and

the Native Americans regard them as beneficial. Not surprising, given that they eat the hoards of insects that

would otherwise eat everything in sight!

I'd like to make one other clarification: people did in fact come to the New World from Asia. But whether they

brought language, symbolism, mythology or artistic technology with them is an open question. It was such a long

time ago - Ice Age, in fact - when mammoths and sabre-tooth tigers still roamed; and dire wolves, and other gigantic,

unfortunately extinct and marvelous creatures. Huge bears, tiny horses - it was cold and life was brutally hard.

But these people were superb hunters - in fact I've heard theories that mammoths are extinct primarily due to human

depridation. And they didn't ride the little horses - they ate them.

Horses, with all their magic, their beauty and their strength, would not roam America again until the Spaniards

came.

Posted by Sophia Gates on 02-05-2002 12:15 PM:

Was Weaving First?

Dear Filiberto:

Thank you for your post!

Yes indeed - Marla has made some excellent points about the origins of design in weaving.

However - there's no real evidence that the Mimbres knew how to weave anything beyond simple sandals made of grass.

As you say the textiles would have decayed anyway - but weaving implements, especially since weaving was considered

a sacred task to many early American cultures - probably would have. And what would they have woven? They had no

sheep, no cotton in significant quantities.

It is possible, however, that via trade with the vibrant cultures to the South, they might have encountered textiles.

It is thought that the superb Mimbres pottery might have been used as trade goods to obtain such products.

Here's another thought: the Anasazi, who lived to the north of the Mimbres, originally in Colorado then later in

New Mexico and Arizona (we think!) - also painted beautiful geometrically patterned pottery. Some archaeologists

think these geometric symbols actually were a type a symbol language. And again, this was not a weaving culture.

Any thoughts?

Posted by Steve Price on 02-05-2002 01:24 PM:

Hi Sophia,

These folks may have been pretty sophisticated in their knowledge of animals, but I'd be astonished if they saw

bats as flying mammals - critters more nearly related to themselves than to birds. Likewise with whales and dolphins

- they are still thought of as fish by most of the people in the world.

I would also point out that their repeated reference to dragons does not attest to an extraordinary knowledge of

biology, notwithstanding the fact that they knew which animals were dangerous and which were edible.

Your main point, though, that similar motifs seen in different cultures don't always mean that there was a historical

relationship through which the motifs were related, is well taken.

Regards,

Steve Price

Posted by Elise Sophia Gates on 02-05-2002 04:17 PM:

Guess who?

Hmmmmm.

Alas, I can’t begin to explain the origin myths of the Mimbres and their fellow Native Americans. They are extremely

complicated and relate many adventures that would make Homer blush with envy. After years of study I am still hopelessly

confused. But it would be interesting to compare with the mythology, if any is written down, of the Mongol people

from whom they descended.

Here you see one of the Warrior Twins looking remarkably like that fine Old Testament fellow with whom we are all

acquainted.

As far as the dragons go – they are a remarkably persistent feature in the legends of people all over the world.

There was an excellent program on the subject recently – I think it was A&E – it’s well worth watching. Some

of the most beautiful art in the world centers on these magical creatures. Personally I’ve never actually caught

one.

Posted by Sam and Barbara Gorden on 02-05-2002 05:39 PM:

Dear Sophia,

You said it all when you wrote "Who's to say that women didn't weave their hopes and dreams and heartfelt

beliefs in their rugs?"

In the study of ancient cultures, it becomes clear that certain functions such as hunting, waging war, etc were

allocated to the male sex and child rearing, family life, etc were in the purview of the female gender. Under the

circumstances, it becomes obvious that it was the women who used the creation of the carpet and other artifacts

to embelish tribal life!

No attempt to appreciate this life is complete without taking the above into consideration. Sam Gorden

Posted by Sophia Gates on 02-05-2002 05:55 PM:

Thank you, Sam! I agree wholeheartedly.

Posted by Steve Price on 02-05-2002 06:48 PM:

Hi Sam and Sophia,

It's true that the women traditionally do the weaving in western and central Asia, but that's men's work in subsaharan

Africa, as is sculpture. And in Asia, most artistic endeavors other than weaving and embroidery are done by men,

as are some of the processes that precede weaving in the production of textiles.

Just wanted to toss this in before anyone gets too deeply committed to the notion that women are artists and men

are grunts.

Regards,

Steve Price

Posted by R. John Howe on 02-06-2002 06:35 AM:

Sophia et al -

I'm going to sound like a "broken record" here.

I think Sophia's indication that similarity doesn't prove common source or connection is sound but we need to notice

what effect this has if we are to be consistent about it at all.

I have repeatedly objected to folks using genetic language when they talk about similarities since it seems to

me that the connections are often both critical and undemonstrated, but Sophia's critique of similarity appears

to go further. If taken seriously, a great deal of the rug literature to date would likely have to be discarded

since the use of design similarity to underpin its theses is nearly universal.

And the odd thing to me is that Sophia still wants to argue for the distinctiveness of some designs but it's hard

for me to determine the basis on which she either accepts or rejects a given thesis. There are lots of flashes

of insight but it's hard to tell when to treat one seriously.

Is it all just artistic musing or can anything at all ever be demonstrated?

Regards,

R. John Howe

Posted by Steve Price on 02-06-2002 08:11 AM:

Hi John,

Strictly speaking, nothing is ever proven. The best we can do is fail to disprove, and when we make repeated efforts

to disprove (using independent methods, not simply doing the same thing over and over) and fail to do so, we pretend

that we have proven. That's the convention.

How about motif similarities and their evolution? Sophia points out, correctly, that similarities among certain

motifs in different cultures do not prove that evolution of those motifs across the cultures is the explanation

for the similarities every time.

Does this mean we must abandon the bulk of the literature on rugs? I don't think so, but it does mean that we must

not abandon our critical facilities when we consider it.

Sophia notes that the same motif can have multiple origins as long as there are creative people in different times

and places. I'm sure that's true and is probably the correct explanation in some cases. But it is - for me, at

least - an explanation of last resort. When the cultures in which two similar motifs exist are (or have been) in

close contact, motif diffusion from one to the other is unavoidable. So, in such instances the question would become

whether it arose independently in both cultures before the contact occurred. This, for many cases, would allow

us to set a time frame on whichever hypothesis we make and that, in turn, suggests ways of testing it.

Another simple explanation for motif similarities across cultures that had no contact is the constraints of technique.

The strikingly similar American and Caucasian bird figures that Sophia posted probably owe their similarity to

the constraints of the weaver's techniques. Once someone decides to draw a bird by a method that only allows horizontal,

vertical, and 45 degree angle lines, the outcome is set within very narrow limits. The bat drawn on the Mimbres

pottery, in which there is no such constraint, looks very different.

Regards,

Steve Price

Posted by Filiberto Boncompagni on 02-06-2002 10:37 AM:

Hi Sophia,

I am rather ignorant on early American cultures, so I did not consider the fact that Mimbres could lack weaving

materials. If they traded with the south that could be an explanation.

Why not? They acquired an expensive, exotic, beautiful textile and they felt the necessity to reproduce its design

within the form of art at their disposition: pottery.

Actually, if they were weavers, why should they copy it(on

pottery)?

Regards,

Filiberto

Posted by Sam and Barbara Gorden on 02-06-2002 02:11 PM:

Dear Sophia and Steve,

THERE ARE ALWAYS EXCEPTIONS! In ancient Greek society, male sexual satisfaction was confined to that gender. Sex

with the oposite sex was justified because it was the ONLY way to procreation. The story is told about the Greek

who emmigrated to the United States with tears in his eyes because HE LEFT HIS BEST FRIEND'S BEHIND!!!

SAM

Posted by Sophia Gates on 02-06-2002 05:53 PM:

Oi vai is mir!

Dear Sam:

You are so right.

But Steve - truly - I had to hold my sides a bit when I read your post. I doubt if ANYBODY is going to claim that

women are the artists of this world while men are the drudges. In so many cases it's EXACTLY the other way around.

Even in my household, I can paint all day, write all night and still be expect to shop, clean, cook and care for

the critters

(I do love the critters...)

Truthfully, that's one reason I started collecting tribal rugs and N.A. pottery - although there are exceptions,

as Sam points out - this is traditionally women's work. And there is so little to point to, compared to the vast

body of men's history - unless of course you point to the men

Posted by Steve Price on 02-06-2002 06:07 PM:

Hi Sophia,

I see you don't hang around universities very much. The Political Correctness that pervades even conservative institutions

like mine would take exactly the position that women are the cultured, artistic ones while the male mentality is

best suited to wielding a club. I simply wanted to head that off.

If you think I'm not serious, let me tell you a little story. About 10 years ago I was the university's Scholar-in-Residence

for our Honors Program. Part of my responsibilities was to present a mini-course on Reunion Weekend. I decided

to offer a 4 hour thing on tribal textiles from western and central Asia. "Tribal Textiles from Central and

Western Asia" is a pretty dreary sounding title, so I gussied it up a bit and called it: "Can a Man My

Age be Happy with an Old Bag?", and subtitled it, "Tribal Textiles from Central and Western Asia."

When the program was printed, the subtitle got left off. The university received an official letter of protest

about the sexist title of my mini-course, signed by all members of one department.

Regards,

Steve Price

Posted by Sophia Gates on 02-06-2002 07:32 PM:

Old Bags

Dear Steve:

Ouch.

Things have really changed. I think it's good though - when I look back even 15 years ago - it was really outrageous.

One vice-president I know used to run around looking up secretarial skirts.

Seriously. He used to lay on his back on the floor and look up.

And this was in a Big Corporation Downtown. In an Actual Skyscraper.

You can imagine what it was like being a belly dancer

It is to laugh! And cry - but mostly - WHY WASN'T I BORN A LITTLE LATER????

Dang.

Posted by Marvin Amstey on 02-06-2002 08:34 PM:

Hi Steve,

What department? I wouldn't think your University would have a women's study department, or have they succumbed

to political correctness?

Regards,

Marvin

Posted by Sophia Gates on 02-06-2002 09:25 PM:

Women's Studies

Dear Marvin, Steve et. al.,

I'm surprised that you might consider Women's Studies to be something of a Political Correctness joke.

All kidding aside, as it is good to have a sense of humor about life, or we'd all go totally bonkers, women are

over 1/2 the world's population. Our minds and bodies are radically different from yours and our life circumstances

are frequently dreadful. Most of the poverty on this planet, even in wealthy America, affects women and children.

Politically and physically, women have and continue to suffer dreadfully - and some of the more radical customs

and attitudes toward women happen to exist in the regions which produce our beautiful rugs.

I do not think it is possible to understand tribal art without understand women's values, our travails and our

uniqueness. Yet we are married off as children in some regions; our genitals are removed in others; we are buried

in unmarked graves. Our men take serial or multiple wives and yes - even in America - divorced women frequently

wind up in poverty.

Meanwhile, the creations of women, our dances and our stories and our poetry, are frequently belittled or ignored.

Only a handful - a HANDFUL - of women painters have ever made it into an art history book. And all too often, women's

creativity, if allowed to blossom, comes at the terrible price of losing her mate, or not HAVING a mate; not having

children; and of course being poor.

In other words - in many societies it (creativity, self-actualisation) isn't allowed at all; in others, the price

paid is virtual ostracism from the rest of society. In still others, work product (rugs, for example) is the property

of the males.

I think Women's Studies ought to be a darn prerequisite for a B.A. It isn't a matter of "political correctness"

- it's plain common sense!

Posted by Steve Price on 02-06-2002 10:09 PM:

Hi Marvin and Sophia,

First - to Marvin: I don't recall which department it was, but it wasn't Women's Studies. And since you know me,

you can imagine how upset I was over the whole incident!

Second - to Sophia: I understand the difficulties of nonidentical treatment of genders in various cultures. If

you want to see total loss of economic opportunity based on gender, take a stroll through Arlington National Cemetery

and compare the number of young men who didn't survive into maturity with the number of women who didn't.

Please don't sterotype me as a male chauvinist. I've supported equal opportunity for as long as I can remember.

My wife is a professional person (MD, obstetrics and gynecology) and my first and most successful PhD student was

a woman (still is, come to think of it). I don't think reciting lists of institutionalized mistreatment is a constructive

approach. It leads to the mindset that you can divide the world into good and bad people on the basis of gender

(in this instance). This doesn't lead to cooperative efforts to find ways to make things better, it generates resentment

and confrontation. If you look carefully at your list of the sufferings women have endured in various societies,

you'll see that the same has been true of men. Genital mutilation? Poverty? Being sold off while still children?

So, it's no stroll in the park being a woman who's an artist? It usually isn't/wasn't for men, either. And just

what percentage of the men in the world do you think have (or had) time or opportunity for self-actualization and

creativity?

Rugs, anyone?

Regards,

Steve Price

Editor's Note: This thread continues on a second page.

Clicking on the numeral 2 at the lower left of the screen will bring you to it.

Posted by R. John Howe on 02-06-2002 10:14 PM:

Steve -

To go back a bit beyond the "male/female" slant this thread has taken, I want to reiterate my suggestion

that Sophia's rejection of comparison seems pretty thorough-going and not as easily disposed of as your own subsequent

post might seem to suggest.

I have no trouble with saying that similarities between designs in culture considerably removed from one another

and with no seemingly plausible means of communication do not indicate anything much. And it's pretty obvious that

some designs, as has been noted several times, are technique driven.

But if you recall, Sophia's initial rejection of similarity was in the instance of Christine Klose's derivation

of the "eagle Kazak" medallion from Persian "vase carpet" designs. One could argue

(and some do, vehemently) that much of the Caucasus was in fact part of the geographic area in which Persian culture

was from time to time very influential. To reject such similarities there seems to require a standard that Sophia

has not I think articulated.

Of course, we can't "prove" most things we talk about here, but does that mean that we give up pretty

much attempting to handle evidence in any systematic ways. (Will we soon be talking again, albeit more politely,

about "baby raptors?" Seeing "crosses" everywhere begins to feel rather close.)

Are we saying, "Come look at things from this steet corner! You'll see new things over here!" There are

such perspectives. I found myself put off at first by Carol Bier's grounding her examination of "symmetry

and pattern" in a theoretical setting seemingly defined by largely by mathematics. It seemed to me that the

"dead hand" of mathematics was likely to smother our ability to enjoy the art --- even that contained

in mere craft. But when I went to her street corner I did in fact see new things in the rugs.

I can't spot the basis on which Sophia rejects similarities seemingly grounded in at least contiguous cultures.

The very distant examples don't touch that observation at all.

Regards,

R. John Howe

Posted by Steve Price on 02-06-2002 10:31 PM:

Hi John,

Either you misunderstood me or I am misunderstanding you. Your previous post seems to be taking issue with my view

of things, but I don't think we disagree. My position, which I think is the same as yours, is:

1. When two cultures that were in contact have motifs that are strikingly similar, the likelihood is very high

- nearly certain - that the motifs migrated from one to the other.

2. When two cultures that had no contact share certain motifs, we ought to look for simple explanations like technical

constraints, and a lot of the time we will find that this suffices.

3. When all else fails, the notion of independent innovation of the motifs in both cultures becomes the only tenable

explanation.

Regards,

Steve Price

Posted by Steve Price on 02-07-2002 06:39 AM:

Hi John and Everyone Else,

Just some afterthoughts to my last posting. I wrote, among other things, "When all else fails, the notion

of independent innovation of the motifs in both cultures becomes the only tenable explanation." Sophia's position

on the independent innovation explanation is that it is a likely one even if all else DOESN'T fail, so some may

wonder why I wait until all else fails before adopting it, and then only tentatively with the hope that some alternative

will pop up sooner or later.

The reason is simple. If it is permitted to override other possibilities in explaining origins of nearly identical

motifs in different cultures, there is no logical reason why it should not be invoked to explain every instance

of the occurrence of nearly identical motifs by different weavers within a culture. In essence, this explanation is almost the same as "it's

a miracle" as the explanation for a phenomenon. It puts an end to forward motion in new understandings.

So, even though "it's a miracle" or "two especially innovative weavers in two different cultures

invented this motif independently" may actually be true from time to time, we must sacrifice those occasions

in order to accomplish anything else. Coming to grips with this fact for the first time is usually unsettling.

Regards,

Steve Price

Posted by Sophia Gates on 02-07-2002 05:18 PM:

I'm Confused

Steve, John, et.al.

I don't understand why "miracles" and "learned behavior" or "copying" can't coexist!

In fact I'm quite positive they do! Within groups and between them, in fact, there are all different sorts of learning

and teaching and creative solutions to problems.

One problem, a really serious blockage to understanding this idea, is the desire to have simple, clear solutions

to problems which can only be understood by the willingness to accept ambiguities and even contradictory evidence,

and to accept it ALL as being possible or true.

Why do we have to exclude one set of possibilities in order to acknowledge another? We aren't computers! We are

animals. We have complex brains and very, very old roots. We have evolved from little cells, through many stages

of evolution. We may, or may not, have been visited by gods or even people from other worlds.

And yet, our written history is very short indeed - let alone our technological, post-industrial history! I submit

we have not begun to learn about our world. One thing I can state unequivocably: if we insist on simple, one-sided

solutions to complex problems, we aren't going to learn....let alone evolve to a higher state!

Posted by Steve Price on 02-07-2002 06:25 PM:

Hi Sophia,

Sooner or later, attempts to learn from experiences and interactions with others and the world require that there

are some rules for testing truth. We can't get anywhere without them. Your proposal is to accept many approaches

to this problem, changing them on the fly when it suits. Here's what's wrong with that. Suppose you tell me that

your intuition says somehing is true. My intuition says it isn't. How do I decide? Does yours trump mine, or does

mine trump yours?

Here's how the charlatans and crackpots of the world tackle this: they say, "Look at my record of success!"

Then they parade before us some instances in which they were right, ignoring the times they weren't. That's why

anecdotal evidence is of so little value.

The logical, empirical approach, by the way, does not lead to onesided solutions to every problem. In fact, many

problems are not solved by it at all. But it's a real practical way to approach a problem, and the evidence that

it works is immediately obvious when you consider how we got to be able to live in a world where people who have

never met can engage in real-time debate like this.

Regards,

Steve Price

Posted by Sam and Barbara Gorden on 02-07-2002 09:22 PM:

Dear Steve,

Your very succinct reply to Sophia's letter reminded me of something I wrote many years ago! "The more I learn,

the MORE I know of how LITTLE I know!" The adjective "INFINITE" can best be applied to "KNOW"!

The latter can be connected with our life's experiences. As these vary, SO MUST OUR KNOWLEDGE!

This is the way our "PERSONALITIES" are built. Sam

Posted by Steve Price on 02-07-2002 09:33 PM:

Hi Sam,

The show, "The King and I" is all about this. There's a wonderful song that the King sings about his

educational development:

When I was a boy,

The world was better spot. What was so, WAS SO.

What was not, WAS NOT.

Now I am a man.

The world has changed a lot.

Some things nearly so.

Others nearly not.

There are times I think I'm not so sure of what I absolutely know....

Regards,

Steve Price

Posted by Sophia Gates on 02-07-2002 09:50 PM:

I'll try again!

Hi folks. OK - another try.

I am not dismissing logic, the scientific process or any other method of learning. I am trying to explain that

there are other ways of knowing.

Why are you so sure that "changing things on the fly" is such a bad idea? Have you ever played jazz?

Have you ever danced to a taksim? Ridden a fast horse over unexplored ground? You would HAVE to be able to make

split-second decisions.

As far as the moments I've chosen to disagree with certain rug analysts: to me they're PERFECTLY logical. What

they are saying doesn't make any sense! Therefore, I disagree with them. I do not care how many times they try

to jam Cinderalla's big toe into the shoe, it won't fit!

I'll make more scans & try again!

Meanwhile, thanks to all for the lively discussion

Posted by Steve Price on 02-08-2002 06:27 AM:

Hi Sophia,

I'm afraid you simply can't have it both ways. Either the logical/empirical approach leads you in the direction

of truth, or the fervor of your intuition does. What you just told us is that your intution trumps logic/empiricism

any time it disagrees with it fervently. That is, your test of truth is intuition.

That's fair enough, and is the truth testing method in every low tech culture that has ever walked the earth. In

fact, it is the abandonment of this as a formal way of thinking that leads to a higher tech culture. Intuition

tells us that you can't build a machine out of metal and expect it to fly. It tells us that the earth is flat,

and that love lasts forever.

There are lots of things we change on the fly. You cite several, correctly. What we're talking about now is not

motor activities, but the method of deciding what is true and what isn't. If you can change methods on the fly,

you don't have a consistent method and can be led to believe anything. If you're OK with that, it's not my problem.

I reject it for myself. That's not your problem, of course. BUT, if we don't use the same rules, it is impossible

for us to debate to a conclusion.

Regards,

Steve Price

Posted by Sophia Gates on 02-08-2002 11:20 AM:

Dualism

Steve:

I'm going to start a new thread on the topic of dualism.

Later!

Best,

Sophia