Posted by Steve Price on 01-21-2002 01:18 PM:

Some Closely Related Items

Hi People,

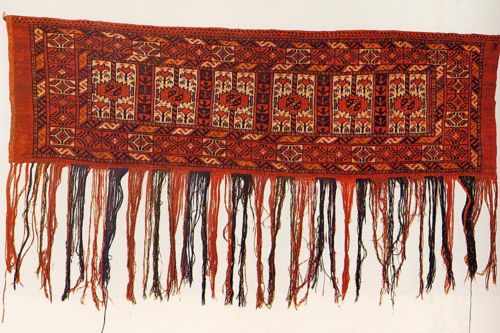

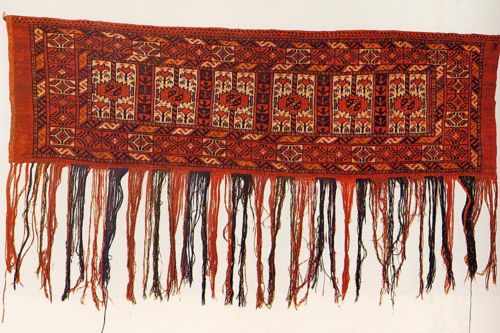

It occurs to me that the six-panel Tekke piece in the Salon essay is, strictly speaking, not a member of the title

group since it's size makes it a torba, not a mafrash. It is so clearly related to the others, though, that I think

it would make more sense to modify the title than to leave it out. Anyway, here it is:

It appears in Bausback's Alte und Antike Orientalische

Knupfkunst (1979; p. 128).

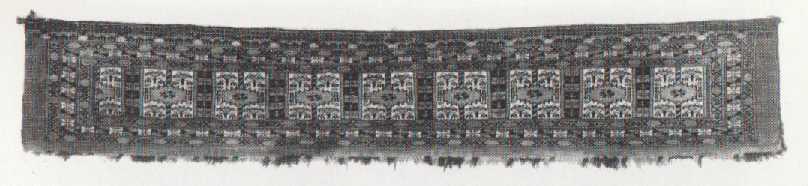

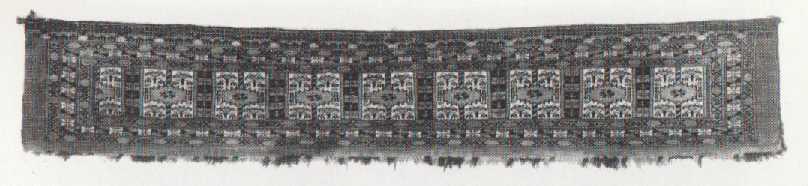

I've seen photos of two Tekke kapunuks, one more step removed from the mafrash format, but still clearly part

of the design group. This one appears in Hans Elmby's, Antique

Turkmen Carpets. II (1994, fig. 8).

We could go further afield, I guess, with the paneled mafrash that don't use the tree of life as the main motif.

On the other hand, those usually differ from this group in many other design features as well.

Regards,

Steve Price

Posted by Patrick Weiler on 01-24-2002 10:57 PM:

Panel Numbers

Steve,

You mention the six-panel design, but are there any one panel examples?

Would a one-panel example be overlooked for inclusion in your survey because it does not look like the rest?

A one panel example would look suspiciously like a mafrash prayer rug.

I seem to be inexorably drawn to the design source question, but could this multi-panel design be related in any

way to the Saph design?

Eastern Turkestan is the source of many Saph rugs. Could this "Family Prayer Rug" design have been appropriated

by neighboring tribal Turkmen weavers and miniaturized into the multi-panel mafrash?

Is there no end to these suspenseful speculations?

Saphomorically yours,

Patrick Weiler

Posted by Steve Price on 01-25-2002 06:15 AM:

Hi Patrick,

Your question about the possibility of one panel designs raises an issue that I had intended to mention.

It seems to be a general truth that Turkmen didn't change the dimensions of their motifs very much in going from

large to small pieces (or from small to large - your choice) - they simply change the number of motifs. This is

clear if you look at ashik gul pentagonal weavings. Big ones, like full size asmalyks, have lots of compartments

with an ashik in each. Small ones, like camel knee covers, have a single compartment with an ashik. But the compartments

and motifs are not very different in size, if they show a consistent difference at all.

The same seems to be the case with these bags. The ones with more than 3 panels are really bigger than what we

would normally call mafrash; they are torba size. If there are any with single panels (and I haven't run into one),

they'd be khorjin size.

Could the layout be based on the saph? I guess it could. Or any other compartmented arangement. Adjacent yurts

with doors all facing the same direction (I recall reading somewhere that this is how they are arranged), houses

with rows of windows, a forest seen through the windows of a train. I don't mean to be sarcastic, and I apologize

if this is coming through that way - I am being serious. The notion of a saph derivation is as good as any other,

better than some, but not good enough to be compelling.

Regards,

Steve Price

Posted by Yon Bard on 01-25-2002 09:14 AM:

Steve, I am looking at 'Antique Turkmen Carpets III' by Hans

Elmby. No. 7 is a four-compartment Tekke, width 63cm. No. 8 is a three-compartment Tekke, width 84cm! (The heights

are about the same, 30 and 32cm respectively). Perforce, the compartments in the 3 piece are much wider than in

the 4 piece. They are wider yet in no. 20, a two-compartment Yomud whose width is 73cm. Your rule about size relationships

doesn't apply here.

Regards, Yon

Posted by Steve Price on 01-25-2002 09:32 AM:

Hi Yon,

You're right about this specific pair of examples, of course, but I think the general rule will hold (that hypothesis

is easily testable)  . I'll

try to compile the dimensions of the pieces this weekend. Most of the sources included this information.

. I'll

try to compile the dimensions of the pieces this weekend. Most of the sources included this information.

Regards,

Steve Price

Posted by Steve Price on 01-25-2002 09:51 PM:

Hi Yon,

I ran the numbers on the width and number of panels of the 24 Tekke pieces in the database. I restricted it to

Tekke because they make up two-thirds of the total pieces, and Iwanted to avoid the possible confounding effects

of tribal variations in size for nominally the same bag.

Anyway, here's the outcome.

The 6 two-panel specimens had an average width of 26.7 inches.

The 14 three-panel specimens had an average width of 27.9 inches.

The 2 four-panel specimens had an average width of 27 inches.

The single specimen with 6 panels was 56 inches wide.

Ignoring the one with 6 panels, there is no obvious relationship between the number of panels and the width of

the piece. It follows from this that the width of the panels must get smaller as the number of panels increases.

Sadly, it follows that my notion of the motifs being nearly constant in size, variations in number of panels being

reflected as variations in width of the pieces, was not supported by the data.

I really hate being wrong.  You'd

think I'd get used to it after awhile.

You'd

think I'd get used to it after awhile.

Regards,

Steve Price

Posted by Yon Bard on 01-25-2002 10:25 PM:

I think the kapunuk shown in this thread and its analogs are

the only other pieces with real close relationship to the mafrashes under discussion, and any serious speculation

(which is the best we can hope for) on the origin of this design should condider the relationship between the mafrash

and the kapunuk. Perhaps people who saw the kapunuks at the yurt entrance observed 'what an interesting design.

Wouldn't it be nice to make similar bagfaces?' Which brings me to the question of whether there is any evidence

that these mafrashes were, indeed, bagfaces and not just decorative trappings? True, many of the mafrashes are

missing their sides, suggesting that the sides were sewn to something, most likely the back of the bag, which was

cut off when sold. But a while ago I have made the same observation about the great Salor trappings (such as the

one in Mackey and Thompson) which are invariably missing their sides, yet are generally believed not to be bagfaces.

So the question is, do any complete (or at least unambiguous) bags

exist with this design?

Regards, Yon

Posted by Steve Price on 01-26-2002 08:02 AM:

Hi Yon,

Your suggestion about door surrounds and these bags being related is an interesting one, and someone suggested

a relation between these and ensis, which are usually also compartmented designs. There are also ivory ground paneled

mafrash with major motifs other than the tree of life (if that's what the major motif really represents in the

group we're discussing).

At least one example is a bag with a back. The Yomud piece in the Salon essay belongs to me and the back is still

on it.

Regards,

Steve Price

Posted by Patrick Weiler on 01-26-2002 10:17 AM:

Get Your Set

Steve,

Now that Yon has headed you down the direction of similar items, would it not be likely that a girl might make

her entire dowry set of weavings with this design? The germetch, the kapunuk, the ensi, the mafrash, the khorjin?

You need to research this a little more and locate that rascally tree-of-life germetch.

Has there ever been a suggestion that a "Set" of dowry items may have been woven in a specific design?

I have seen a few matched items, such as plates 48/49 in Woven Gardens by Black and Loveless showing a mafrash

face and matching salt bags. Was this a common practice?

Check out the pawn shops in Dushanbe Tajikistan.

Patrick Weiler

Posted by Steve Price on 01-26-2002 01:13 PM:

Hi Patrick,

I have never seen any information one way or another about whether Turkmen women/girls wove matched dowry ensembles.

It's an interesting thought. We need to get our hands on some 19th century issues of the Turkmen language edition

of Bride

magazine. Most likely, it will include John Howe's central Asian shield-shaped bag.

Regards,

Steve Price

Posted by R. John Howe on 01-27-2002 08:28 AM:

Dear folks -

There is an article by Mogul Andrews (OCTS?) in which she recounts once observing a Yomut girl weaving her "wedding

rug."

Andrews say that some clear rules were observed. For one thing, the young woman would not talk while she was weaving

this piece. She said that she should not be having thoughts not related to her marriage while weaving it.

On the other hand, and a little surprising perhaps, the design used did not seem to be of particular importance.

The weaver had gone to the market and purchased a cartoon that Andrews said seemed popular among prospective Yomut

brides just then but that was not a traditional one for this particular tribal group. I think it may not even have

been Yomut at all.

Now this observation took place fairly recently, I can't recall exactly but certainly not before the 1950's, and

it seems likely that many 19th standards that once governed tribal rug weaving might have been lost some time back

but I remember being surprised that the still visible rules for making this dowery piece no longer seemed to prescribe

pattern.

This kind of thing makes me wonder if our speculations about the likelihood that Turkmen weavers might weave pieces

with matching designs in their dowery weaving might not be an instance of romantic projection from our side.

Regards,

R. John Howe

Posted by Steve Price on 01-27-2002 08:58 AM:

Hi John,

I don't know how serious Patrick was in his suggestion that dowry weavers might make matched ensembles - my suspicion

was that it was a sort of offhand thought being thrown into the mixing bowl. I have seen no information on the

matter one way or the other. However, in the absence of some reason to think otherwise I would take the system

that Andrews observed as the continuation of a fairly long tradition rather than as something new to the mid-20th

century.

Regards,

Steve Price

Posted by Patrick Weiler on 01-27-2002 11:10 AM:

DRAT !

Steve,

DRAT!

You have found me out. Many of my suggestions are like those of the blind man  trying, by touch, to identify the elephant without being able to see it.

trying, by touch, to identify the elephant without being able to see it.

Yes, I am merely poking and prodding at this tree-of-life of mafrash, prying and tweezing at it until it reveals

it's secrets.

Hopefully I will not destroy it in the process!

Tweezingly yours,

Patrick Weiler

P.S. No, I am not saying that I see any elephants in your mafrash!

Posted by Christoph Huber on 01-27-2002 11:31 AM:

Ersari Trapping

Dear all

Lefevre & Partners, London offered at an auction on 4th July 1980 an 8½-panel-trapping:

The catalogue entry reads:

36 Ersari Trapping Turkestan

1m67 x 0m33, Second half 19th century, 5'6 x 1'1

It seems that panels such as this were woven to serve as animal trappings used on ceremonial occasions. They are

often decorated with certain ancestral designs which do not appear in other weavings of the group, making their

exact attribution rather difficult. The design of this interesting artefact is closely related to that of the early

Saryks.

The piece has a dense and lustrous pile, woven in the asymmetrical (Persian) knot, and is in excellent condition.

The flowers, mentioned in the other thread too, are really very Saryk-looking. Some of these flowers on the Saryk

mafrash in the Dudin collection are offset-knotted and in this way emphasise their connection to the flowers we

know from Saryk ensis. Though they always remember me to the embroidered Tekke asmalyks as well.

Best regards,

Christoph

Posted by Steve Price on 01-27-2002 11:39 AM:

Hi Patrick,

I think running half-baked ideas up a flagpole to see if anyone salutes is a good way to stimulate discussion.

Half-baked ideas are usually wrong, but that only means that they shouldn't be pushed as anything more than what

they are. Once in a great while one will turn out to be right, and it's not uncommon at all for a speculation to

provoke a useful train of thought.

Regards,

Steve Price

Posted by Marvin Amstey on 01-28-2002 09:57 AM:

Some of those off-hand speculations are so important that they

win noble prizes, e.g. Watson and Crick's explanation for the structure of DNA. Not bad for just sitting around

in an armchair and speculating.

Regards,

Marvin

Posted by Steve Price on 01-28-2002 10:16 AM:

Hi Marvin,

I'd add only one thing, mostly for the benefit of the folks out there who are not scientists by trade: there were

LOTS of steps between the armchair speculation and the model that Watson and Crick developed for the structure

of DNA. The speculations were the origin of the thinking (and hard work) that led to the progress, and were modified

many times as the work proceeded.

We get in trouble when we forget that our speculations are not the end, but the beginning of the trail.

Regards,

Steve Price

Posted by R. John Howe on 01-28-2002 08:08 PM:

Dear folks -

Yes, and if I remember correctly Watson's telling of it in "The Double Helix," some of these steps included

cultivating romantically some young lady who had access to some competitive useful research in this area by others.

Shows that the nicely layed out version of "the scientific method" that Steve has championed here suffers

from (among other things) what might be called a "severe anthopological insufficiency." People and their

foibles will intrude.

Regards,

R. John Howe

Posted by Steve Price on 01-28-2002 09:16 PM:

Hi John,

James Watson is not one of my heroes, and I recommend his book ("The Double Helix") to anyone interested

in reading a morally challenged opportunist's account of how he got to the Nobel Prize. He wasn't embarassed about

it.

I'm not at all sure what gave John the impression that I was unaware of the role of human foibles in academic research.

I've been in the business for more than 40 years, and have seen plenty and given it more than a little thought.

Some time I'll give you my nickel lecture on the role of unconscious bias. It's important to remember that the

scientific method and the ethics of the practitioner are not the same thing. Watson and Crick's application of

the scientific method was flawless. Their ethical standards were not. The fact that I don't admire him doesn't

alter the fact that he knew how to analyze data and construct persuasive arguments with it. In the end, he won

the race for the prize. That, to him, was more important than his integrity. We all face similar choices fairly

often, although usually with much smaller stakes.

Regards,

Steve Price