The Salon du Tapis d'Orient is a moderated discussion group in the manner of the 19th century salon devoted to oriental rugs and textiles and all aspects of their appreciation. Please include your full name and e-mail address in your posting.

by Steve Price

Tribal textiles, like most tribal arts, were not made primarily as expressions of artistic psyches or as purely decorative objects: they were useful in one way or another. The usefulness that seems to attract most collectors first is the symbolic or supernatural powers that some objects were thought to have within the cultures they came from. There's something really fascinating about holding an object that someone believed could communicate with the Gods and maybe even get them to act according to the owner's wishes. On a more mundane level, most tribal textiles were utilitarian objects. For pastoral nomads, wool was the raw material from which they made their garments, their homes, and almost all the furnishings.

One of the pleasures of collecting tribal textiles is trying to figure out what use a particular object had. In a general sense, it's usually easy. A bag is a container for something. Try to get more specific, though, and it's not as easy as you might think. Let's run through a little list of Turkmen products, and you'll see what I mean.

Juvals: This is the largest bag made by the Turkmen, and seems to have been made by every Turkmen tribe in fairly substantial numbers. It's typically a big, flat envelope, perhaps 3 feet deep and 4 or 5 feet wide. Size varies with tribe, but those dimensions will be approximate for the type. What did they put in them? The conventional wisdom is that they were containers for clothing like shirts and trousers. That makes sense, of course. Such clothes are pretty large things, so you'd need a pretty large container. And using containers like this would make it easy to keep appropriate kinds of clothes separated: men's and women's; clean and dirty; and so forth. Just like we do in our cultures. But let me offer something to make you think again:

It's a Tekke ak-juval ("white juval") that you might remember seeing before. The thing about it that I want you to notice is the goathair ropes sewn to the sides, and the closure rope at the top. See how the ones at the sides are sewn tight except in two places on each side (at the edges of the white bands)? In those places it's left unsewn and instead of being tight against the edge of the bag, it forms handles. The edges of the bag show obvious signs of abrasion right under them. It's hard not to think that the thing was lifted by two people, each holding onto one side of it. That seems kind of odd for a clothes bag, don't you think? Then look at the closure rope. The end is frayed off. Not cut off, frayed off. If you string it tightly through the openings in the top of the bag, it gets to about one foot from the end. That is, it looks like it was laced and unlaced repeatedly (until it frayed and broke) in order to open and close the bag at the right hand end, opening it by only one foot each time. That doesn't sound like a very good way to get at clothes in a bag like this, does it? I think this was a grain bag. That would account for it taking two people to lift it, and for the way it opened. Did other juvals serve a similar purpose? Or was the juval a multi-purpose format, some specimens being for clothing and others for grain? Or was the same bag sometimes used for one thing, sometimes for the other?

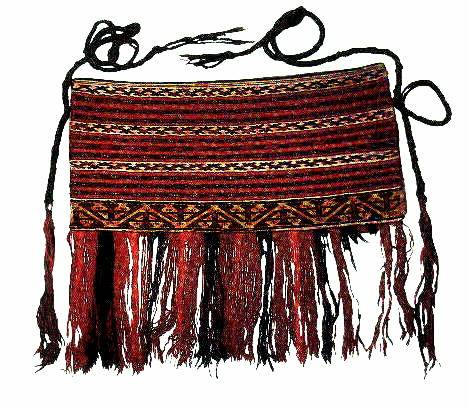

Torbas: These are bags more or less the same width as juvals, but generally only about 18 inches deep. Most folks believe that they were for smaller items of clothing: socks, gloves, and so forth. Perhaps also for cooking utensils, amybe even for food. For many of them that seems reasonable, but the dimensions on others are so wide relative to their depth that it would seem awkward to use them for storage. Here's an example.

This isn't an extreme example, but it serves to illustrate. Were things like this used to store long, slender items like tools of one sort or another? Were they trappings?

Mafrash: These are small, "landscape format" bags. Here's one you've seen before.

Personal belongings seem like a reasonable guess for the use of such things. But which personal belongings? Drugs? Tobacco? Money? Jewelry? All of those things? None of them?

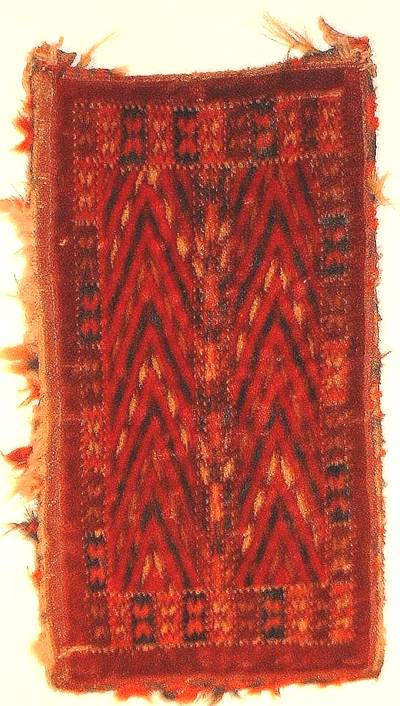

Spoon (spindle) bags: These are the small, "portrait formal" bags, and may be my favorite category. They had pompoms hanging from them at the bottom and both sides, so they were surely pretty decorative when hung in the tent.

One of the things about these that I find so interesting is how they are described in the literature. Some authors call them spoon bags (containers for long handled cooking spoons), others call them spindle bags, and some use both terms. In Wie Blumen in der Wuste, there is one page will several of these illustrated, some labeled spoon bag, others labeled spindle bag. Is there some way to know what one of these things contained when it was in use?

The Turkmen made all kinds of things. I suspect that most were containers although the backs (if they ever existed) are usually gone and that makes it hard to know for sure. Amos Bateman Thacher's classic book includes a Yomud asmalyk that he clearly believed was a storage bag, used with the apex at the bottom. It isn't at all clear to me to what use they put the ubiquitous khorjin, for instance, or whether the ok-bash served as a container when not covering the ends of tent struts. I'm sure our readers know of more puzzles, and I hope they will bring them into the discussion.

We've had related topics come up from time to time (cf., Salon 37, on pentagonal weavings), so the notion of wondering what uses things had is not a new one for us. Perhaps by focusing on this question for two weeks we can shed some light.

Steve Price