One reader asked me on the side the following question. As it may be of general interest I prefer to answer onto the board.

Question asked:

I noticed that the rugs you posted in the thread in which you gave the Harvard link and talked about religious influences are quite young. Is it your view that the "authentically Kurdish pieces" can include say early 20th century material?

I will simply answer YES because they "stay in the tradition" and will develop my thoughts here below.

First of all very few old, let’s say before 1880, Kurdish rugs are available as the market wasn’t organized to export great quantities of them and as they were produced almost for local use. By chance, I have recently examined an old Kurdish rug which I feel to be "authentic". I mean here, as the term was confusing, "being in the tradition".

OK, but what’s the "tradition"?

This small summary can help to give you a better idea of what I mean:

The Kurdish weaving tradition is:

1/ traditional large scale geometric design and few small scattered motifs to correspond with the height of the pile, inherited from more restrictive flatweave technique or borrowed from neighbor sources but adapted in their own way, or traducing old tradition like ancestral religious beliefs… look at the snake-like forms, symbol of the devil, drawn in the two Yezidis rugs, woven somewhere in the vicinity of Mosul, that I have showed in a previous thread.

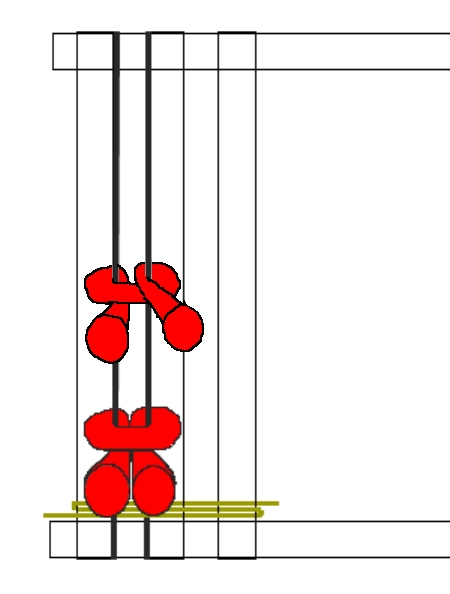

2/ traditional weaving structure - to cite the most important:

In their pile rugs : a coarse weave without warp depression, an all 2ply wool construction with often goat hairs, and in some case cotton for white highlights or metallic wrapped cotton.

In their flatweaves; various kind of brocading (reciprocal, overlay-underlay), soumak and weftless soumak, slit tapestry weave and paired warps tapestry, warp faced and warp substitution weave.

In their end finishes: weft faced skirts adorned with rows of twinning, oblique interlacing or more distinctive oblique wrapping,

And last flat large selvages interlaced by the ground wefts and reinforced with additional colored wefts in bands of contrasting colors.

3/ traditional very saturated colors with a distinctive palette containing some colors cherished by Kurdish weavers like salmon, pink, orange, yellow and white outlining of the design.

4/ and last traditional long pile silky mountain wool, a heavy and floppy handle.

I am not allowed to publish the picture of this old Kurdish rug but it is closely related in design and structure (see below if it gets your interest) to one rug woven by the Goyan tribes, illustrated in Eagleton’s book (plate 72) , reproduced here below. Other examples also related to this rug are, a Goyan rug from Alberto Boralevi published in James H. Klingner article in Hali 105 page 84 and another Goyan rug is on display onto Cloudband in Alberto Levi’s gallery.

According to Eagleton, the Goyan tribe was probably once a section

of the Hartushi, which is by far the most important tribe in the South

East Turkey Hakkari region. They are located just above the Iraki frontier

near the town of Uludere, situated midway between the towns of Cizre

(Djezire) and Hakkari.

Please respect our policy and don’t discuss this rug which is for sale.

Is the old Kurdish rug I have handled an authentic rug staying in the continuum of old traditions? Yes.

Look how many of the characteristics summarize in the introduction to this topic are combined in this rug.

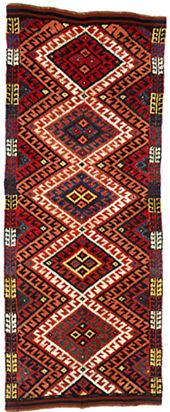

Use this photo to imagine it : Eagleton’s book (plate 72)

PHOTO

In this old "authentic" Kurdish rug, may be a divan cover, 5 1/2 concentric large scale hooked diamonds, may be coming out of more restrictive weave, are vertically aligned on the field surround by a simple main border containing herringbone motif. The colors are very saturated and the palette related to the Eagleton rug is typically Kurdish with various shades of madder red, indigo blue, yellow, brown, green, white and salmon.

It’s sizes, 269cm x 105cm are in the familiar long and narrow East Anatolian format and its handle heavy and floppy as one would expect for this type of rug.

It’s structure is in the continuum of the more early primitive filikli rugs

The wool is a mountainous silky wool and the pile height is about 1cm to 2,5cm. Thick (4 singles) symmetric knots are tied on four 2 ply tan wool warps, like jufti knots. The density is very coarse with only 18 knots per square inch and 10 to 14 wefts (single in various colors) separate the rows of knots.

As it is may be a divan cover the selvages haven’t any special treatment. At top and bottom there is a small skirt measuring 3" in weft faced plain weave with blue and red strips. End finishes are usual oblique interlacing..

Thanks, Daniel

Eagleton plate 72 (structure analysis adapted to Marla Mallett nomenclature)

Type: Van-Hakkari – Goyan tribe – circa 1940

Sizes: V345cm x H104cm, V11’6" H3’6"

Knots: symmetric, wool, 5’ x 5’

Warps: tan wool.

Weft: tan, red, white, yellow wool wefts, 4-5 picks

Selvage: flat interlaced selvage.

Ends: one type of oblique (interlacing or wrapping) end finish

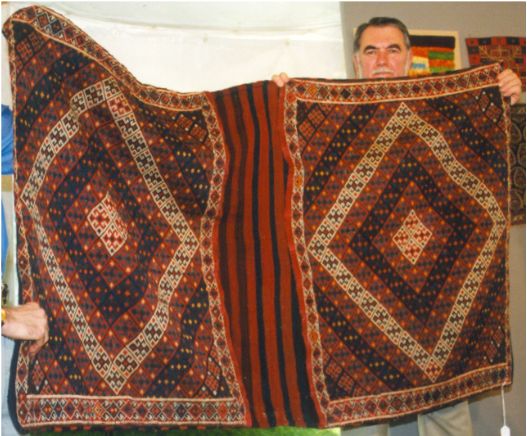

Old Kurdish rug (divan cover) with 5 1/2 concentric hooked diamonds.

South East Anatolia - May be Goyan tribe – circa 1870

Structure analysis:

Sizes: V 269 cm x H105 cm;V9’ x.3’6" (end finishes included)

Yarn: spin Z

Knots: symmetric, wool, 4 singles tied on 4 warps, pile height is about 1.5 – 2,5 cm – density : H3,5pi V5/pi 18psi

Warps: two ply medium tan wool; no depression.

Wefts: wool singles dyed red, brown, dark ,blue wool, 10-14 picks, wefts don’t cross.

Selvage: no special treatment (divan cover?)

End: 3" in weft faced plain weave skirt with blue and red strips - oblique interlacing