The Salon du Tapis d'Orient is a moderated discussion group in the manner of the 19th century salon devoted to oriental rugs and textiles and all aspects of their appreciation. Please include your full name and e-mail address in your posting.

by R. John Howe

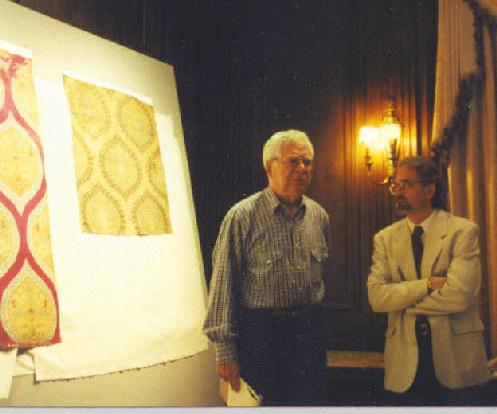

Once each year, The Textile Museum Rug and Textile Appreciation Morning program, one of a series of free, open-to-the public sessions held most Saturdays at 10:30 AM, is conducted by Ed Zimmerman and Michael Seidman.

Ed was President of the TM Board of Directors for 10 years and Michael is a scientist, who

is also a close student of rugs and of textiles.

The sessions Ed and Mike conduct are exceptional, in part, because they always offer a chance for participants

to see up close and directly, material from The TM collection. Often this material has not been exhibited for a

number of years and may well not be seen again soon.

Ed and Mike usually attempt to title their program with the worst pun they can construct.

One recent year, they talked about one Turkmen subgroup under the appalling rubric of "Ersari?

You Needn't Be." This year's session "Other Ottomans," provided only a less-than-attention-getting

alliteration and no pun. No matter. Not only did world class material and an exceptional presentation triumph,

but "Other Ottomans," was usefully accurate in signaling what was distinctive about this program.

The major exhibition currently on the boards at The TM, is Sumru Krody's fine work "Flowers of Silk and Gold: Four Hundred Years of Ottoman Embroidery."

Ms. Krody's book on this subject, has been published simultaneously.

Across town at The Corcoran Gallery of Art there is currently another exhibition of a wide variety of Ottoman jewelry,

textiles, weapons and other art, entitled "Palace of Gold and Light: Treasures from the Topkapi Palace, Istanbul.

"

With this plethora of Ottoman art in Washington at the moment, "Other Ottomans," said accurately that

this program complemented these others but was distinct from them.

Ed Zimmerman set the historical background for the pieces to be seen. He said that one sense in which they were

distinctive is that they date from the 15th to the 17th centuries, a little older than the pieces in the Krody

exhibition.

During this period, Zimmerman said, the rule of the Ottoman sultan Suleyman overlapped that of the first Moghul

emperor, Akbar by about 10 years. For this reason, Ottoman textiles in this Rug and Textile Morning program were

likely not much influenced by Moghul usages, a likely conjecture, since designs in both of these traditions often

importantly include flower forms.

On the other hand, Italian designs were likely available to these Ottoman artists, since not only are there Italian

textiles from this period in the Topkapi Palace collection but, as Washington, D.C. dealer and collector Harold

Keshishian noted from the audience, the Italians had textile "factories" in Turkey at this time licensed

by the Ottomans to make such textiles for them.

Thus, despite the fact that the ancestors of the Ottomans came from Central Asia and that Bursa, the early Ottoman

capital, sat on The Silk Road, plus the further fact that similarities between Ottoman designs and some in Central

Asia and even further East have been noted, the presence of Italian textiles indicates that it is best to acknowledge

that there were likely multiple sources of Ottoman textile designs and that often it is no longer possible to sort

these out.

Having set the historical context for these Ottoman weavings, Zimmerman said that among the interesting questions

that can be asked about them are: Why are flowers so prevalent in these designs and, is it possible detect which

of them were made in Bursa and which in Istanbul?

Ed Zimmerman also noted that TM records indicate that Mr. Myers, The TM founder purchased most of the pieces we

were going to see in 1951 from a dealer named Kelekian. Ed asked Harold Keshishian if he recognized this name.

Harold indicated that Kelekian was one of several high end dealers who had this kind of material then. They were

of a generation somewhat older than Harold's father. Harold said that he was acquainted with Kelekian's son and

that Kelekian's daughter now runs the firm in Paris and still has a great deal of such material.

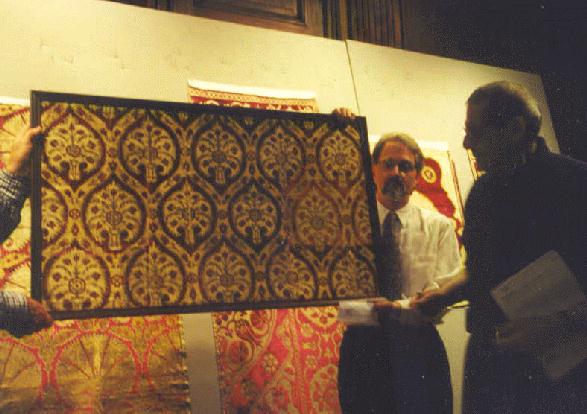

Michael Seidman then began to go through the sixteen pieces that had been brought out from the TM collection. He

noted that the fabrics in these textiles are silk satins and velvets and were likely used for clothing and for

a variety of covering functions, including, in some instances, floor coverings. He noted that some are a little

faded now but that the colors we can see suggest something about the brilliance many of them exuded when new.

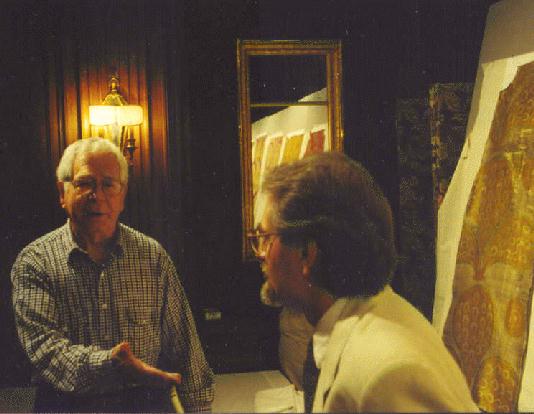

I took a number of photos of this program. Since the use of flash is not permitted with Textile Museum materials,

all these photos were taken without it and often have dark areas, especially on the faces of the participants.

Nearly all of the pieces in this program have been photographed as part of the TM's continuing documentation of

its holdings. I may, emphasis on "may," ultimately try to obtain a set of these images and permission

to scan and to place them with labels and a bibliography at the end of this essay. Meanwhile, there seems no reason

to delay your virtual enjoyment of some glimpses of this program.

The first piece was a clothing panel.

Seidman said that this piece is rather famous and that its "peacock" design is made entirely with metallic threads. Very narrow strips (smaller than 1mm) are wound around silk thread to make the metallic threads with which the metallic portions of such pieces are woven. Seidman also noted that the structure of these satin fabrics is very complex. They are composed of two separate "planes." The patterning in the fabric is in the top plane, the warps of the back plane are binding warps that pass through both planes to secure the patterning wefts on the face of the fabric. This complicated structure required two weavers and considerable time to set up.

This second piece is also part of an item of clothing. It has a red ground with a serrated

leaf design in metallic thread. Seidman pointed out that this design has at least two visible levels with the serrated

leaves both floating on the ground color and crossing one another at points.

Seidman said that parts (often the centers) of some of the designs can be used to some extent in dating the fabrics,

since it is known when certain design characteristics first emerged. In some cases, he said, the designer would

have to have had some knowledge of how a design he was creating would be woven in a textile and that the identity

of the designers of some of these textiles is known

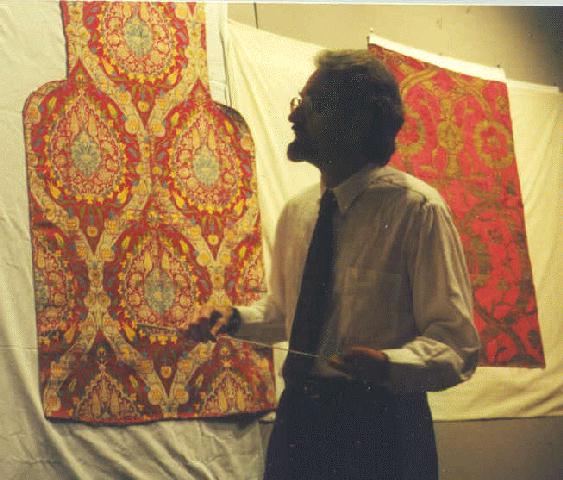

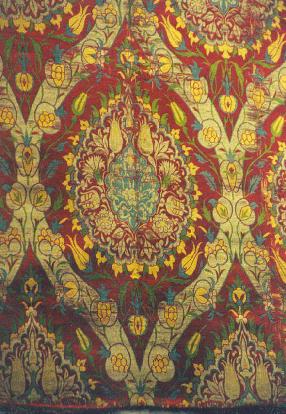

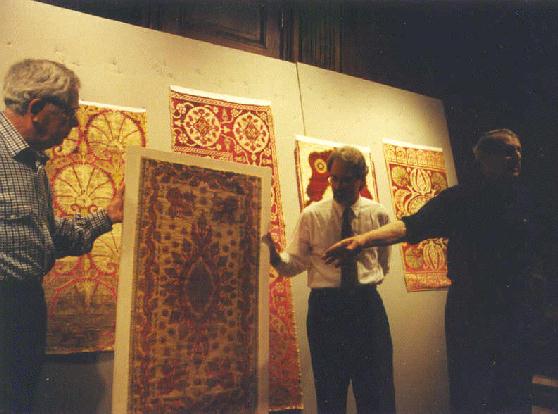

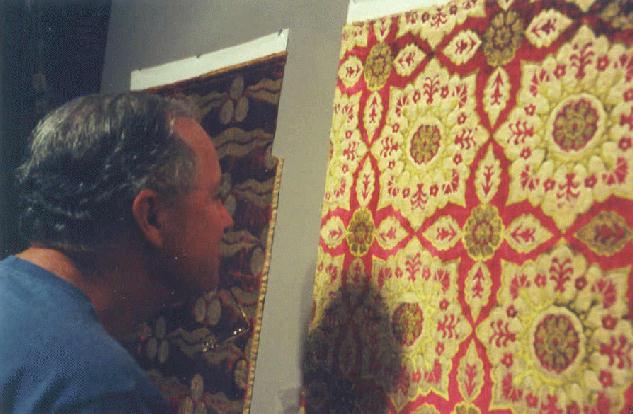

A little later in his talk, Seidman encountered this dramatic, sumptuous piece.

Attributed to the 17th century, Mike said that it was noticeably "Italianate."

To truly take in the rich complexity and detailed drawing in this design, you need to be a

little closer.

In answer to a question from the audience, Michael said that all the silk satins being shown are varieties of "brocade"

and that none of them are "damasks." He explained the distinction, saying that brocade patterns are made

by laying additional wefts into a ground grid of warps and wefts, while damask patterns are made at the level of

and with the materials of the basic structural grid. Looking back at the incredible material on the board, he smiled

and said in mock apology, "Sorry, no damasks."

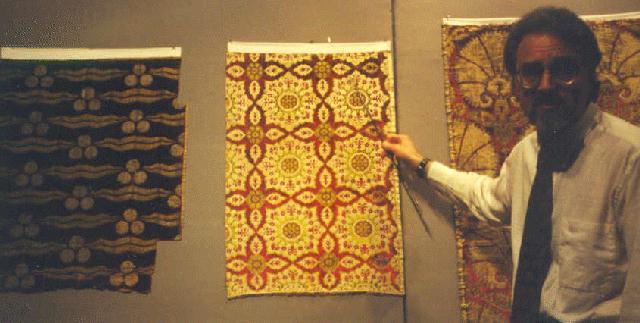

The third and last sequence of textiles displayed on the board started with the piece on the left in this photo.

Seidman noted that this design with the three round disks and wavy "tiger" stripes

has been both written about and conjectured about extensively. The piece dates from the 17th century (a huge, very

attractive, red ground pile carpet in the Corcoran exhibition of Topkapi materials has a version of this design).

The center textile to which Mike is pointing in the photo above is a 17th century "roundel" design.

The third piece on in this third level on the board is a "carnation" design, again gold on a red ground

with an additional subtle blue.

You can't see it but the design of this piece is replicated in Michael's TM Book Shop tie.

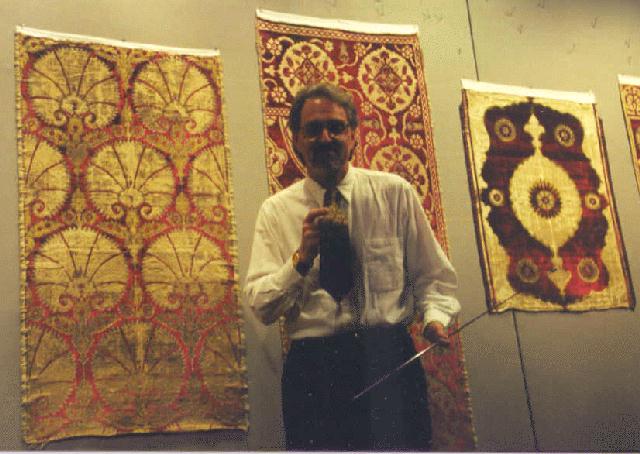

I asked Mike for a photo opportunity and he complied.

The piece directly behind Michael in the photo above is perhaps part of a floor covering. It is very finely woven

and the ivory in it moves between two levels to play different functions in the design. The entire piece may have

been 15 feet long. Notice that the designer has executed a completely finished corner resolution on this piece

without resorting the usual mitering move in which the device that occurs in the corner is angled at 45 degrees.

This piece has a simple anchored medallion design. It has lost its borders.

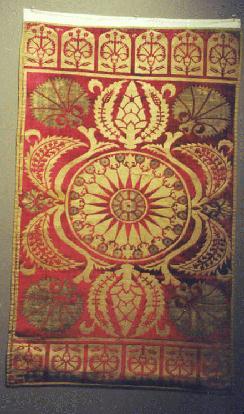

A final piece from the TM material presented is this late 16th century pillow cover with strong

graphics. The detail in its "lappets" demonstrates what the more urban versions of this feature, that

we also encounter in tribal yastiks, were like. This cushion cover will be in The Textile Museum's upcoming Collections

Gallery exhibition, entitled "Considering Excellence: Great Works from The Textile Museum Collections"

opening June 30, 2000. The exhibition will run until November 5, 2000, so this is one piece in this Rug Morning

that you will be able to see again soon.

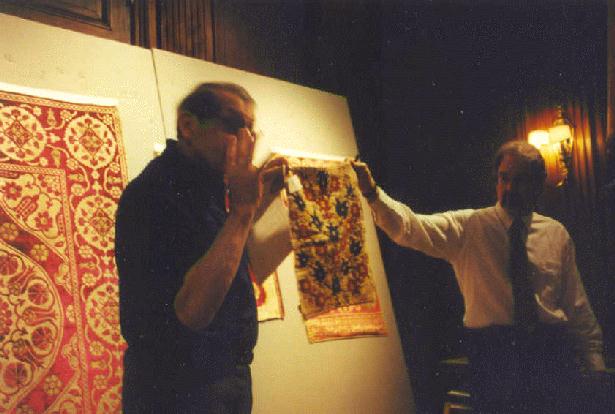

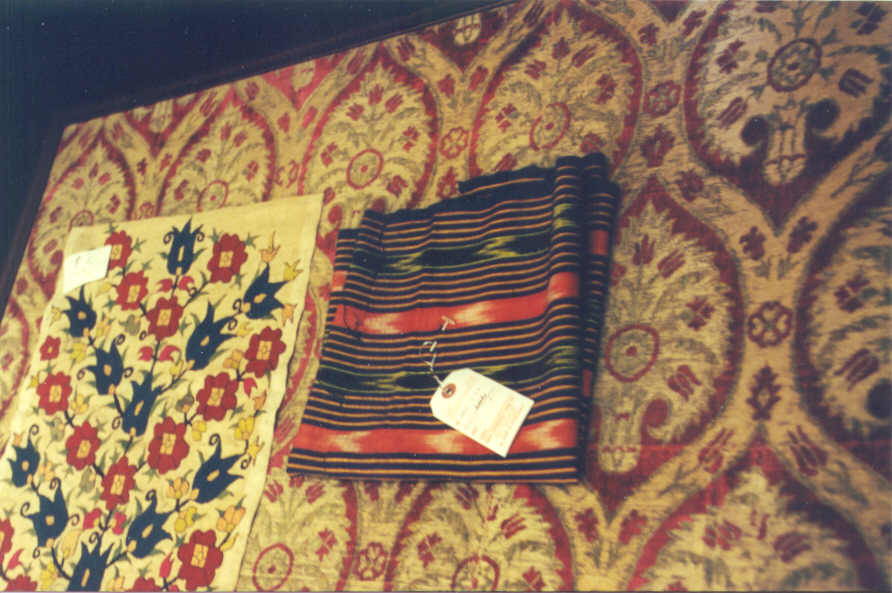

Harold Keshishian, who has had a life-long love affair with rugs and textiles had brought some related pieces of

his own and was invited by Zimmerman and Seidman to talk a bit about them.

Harold described his first piece as 17th century made of velvet and silk with areas of metallic

thread.

Harold's second piece looked like this.

Harold said that it was a yastik with a medallion design that had visible Italianate influences, reflecting the trade between the Venetians and the Ottomans that already existed in the 15th century.

This was a small piece of embroidery. I'll show you a better image of it in a minute. Harold said that it is probably from either Epirus or the Ionia Islands. Despite having been made about 1700 it still has the Turkish tax collector's stamp attached to it.

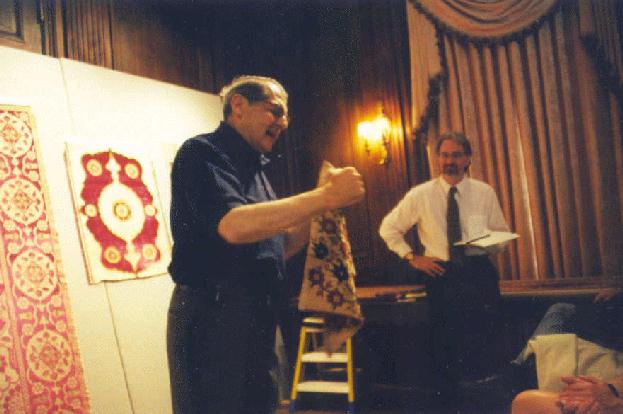

As you can see, Harold can get excited about textiles.

Last, Harold had a piece of Turkish ikat. Since he had asked me once when I brought him a piece of what I thought was Central Asian ikat with a very similar design, how I knew it was from Central Asia rather than from Turkey, I turned the tables by asking him how he knew this piece was Turkish. He said that he had bought it from a lady missionary who had spent many years in Turkey and who said it was the only piece of Turkish ikat she had ever seen. In subsequent discussion, Harold and I have agreed that distinguishing Turkish ikat from Central Asian ikat is very difficult. We're not entirely sure what the distinguishing features are.

The program ended with deserved applause and folks crowded to the front to look at the pieces close-up (it could be a long time before these TM pieces are exhibited again).

Here's the promised closer look at three of Harold's pieces.

So that's the end of the most recent version of the "Ed and Mike" show. They do it very well and we always

go home not only gratified about the chance to see some great material but a little better informed about it as

a result of their careful preparation and presentation.

'Til next year, guys! Work on the pun.

It would be good to hear from anyone about these Turkish textiles themselves and/or about seemingly related pieces.

But I suspect most of us do not have sufficient acquaintance with such textiles to sustain a two-week discussion.

For that reason, I want to suggest that we also reconsider an old question that continues to pop up in various

forms. That is the seeming widespread belief that older materials are better, in some sense, and its seeming corollary

is that younger textiles are (or at least should be) usually beneath the "serious" collector's consideration.

Why is this so? Is it, in fact, an accurate depiction of what exists? Is it not so that art (in textiles) can be

produced in any age? I notice some more experienced collectors seem more and more attracted to things that are

very old generally? Is the age of a textile itself a defensible criterion of merit? Why and how is this so?

And since age distinctions within the particular period in which most of us collect are not really yet very discernible

with even the best current scientific methods, aren't we kidding ourselves a bit about our ability to determine

accurately the age of most of the textiles we own or study? Are we not in fact making most of our age estimates

on the basis of not particularly defensible conventions? Are we in the odd position of claiming that the age criterion

is rather important while at the same time having to acknowledge that we can't in fact use it very effectively

in our collecting decisions?

Would it be better to simply stop attempting to use age at all and to move to posture in which we collect simply

on the basis of personal aesthetics?

And although similar discussions have occurred on our Show and Tell board, the fact of the

very clear Italianate influences visible in many of these very old Turkish textiles raises for me again the issue

of "copying" and its role in our judgments of what is collectible. We often hear denigrating sentences

about copying. But many of these textiles may be rather close copies of the design on 15th century Italian velvets

and it doesn't seem to trouble us much at all. I also heard a TM speaker argue that a Turkmen daughter being taught

by her mother to weave the designs of their particular tribe is doing more meritorious copying since she is working

within a tribal tradition but if we attempt to do the same a great deal is lost because we are necessarily working

outside it. What do we think about copying and its affect on aesthetic excllence?

Regards,

R. John Howe

Informal Bibliography

Essen Atil's catalogue of the Suleyman exhibition at the National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., 1987.

Patricia Baker's Islamic Textiles.

Catalog for the current exhibition at the Corcoran Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., "Palace of Gold and Light:

Treasures from the Topkapi Palace, Istanbul."

Walter Denny's article in the Textile Museum Journal, 1973.

Krody, Sumru. Flowers of Silk and Gold: Four Hundred Years of Ottoman Embroidery, 2000.

Levy, Emile (editor) La Collection Kelekian: Etoffes et Tapis, d'Oriente et d'Venise. Introduction by M. Jules

Guiffrey and remarks on the Collection by M. Gaston Migeon. Libraire Centrale des Beaux-Arts, Paris, n.d.

Mackie, Louse W. The Spendor of Turkish Weaving. Washington: The Textile Museum, 1973.