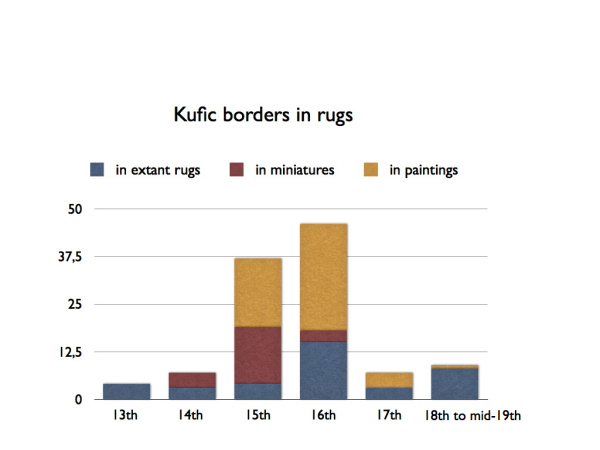

Timeline of Kufic Borders in Rugs

by Pierre Galafassi

Martin’s well documented and credible theories about kufic rug borders and their relation to kufic script in architecture, artifacts and manuscripts (http://www.turkotek.com/misc_00130/kufic.htm), has triggered a few questions about when and where this particular type of motif started its long career in rug borders. To help answer this interesting question, a timeline of kufic "script" in extant carpets, in Persian miniatures and in paintings of European masters between the 12th and 18th centuries (1, 2) could be quite useful. The table below shows the frequency of kufic borders in rugs during this period.

Figure 1

A few comments:

Abbasid period

A tiny fragment found in Fostat shows that kufic borders where already woven during the Abbasid (3) Arab dynasty in the 9th century (4, 5).

The kufic motif is woven in white wool on a deep blue background. It is

possible, but rather unlikely, that this type of border was exceptional

at the time.

Figure 2: 800-900. Abbasid period. Rug fragment found at Fostat (Cairo). MET

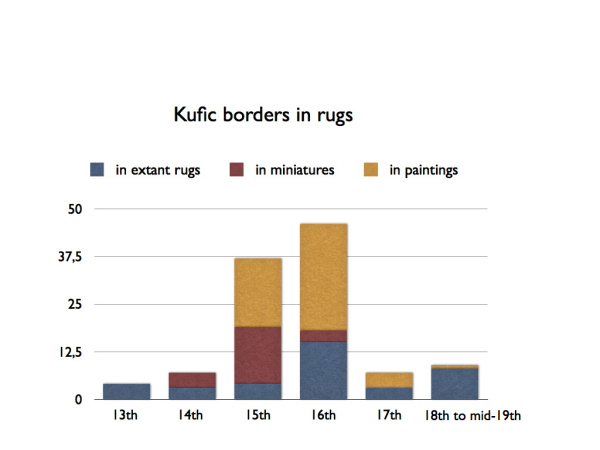

Seldjuk period.

The next group of extant

"kufic rugs" (mostly fragments), dated from between 1200 and 1300 by

the C14 method, were found partly in Fostat (Cairo), partly in Konya

and Beysehir (Anatolia), and partly recently emerged from Tibetan

temples. They are tentatively attributed to the Seljuk dynasties (Great

Seldjuk Persian Empire and /or Anatolian Seldjuk of Rum), but the

question of their precise geographical origin is still

open. Contrary to the Abbasid fragment in FIG 2 and to all later

kufic borders, the Seldjuk kufic borders were not exclusively woven in

white on a dark background; a significant proportion were woven in dark

red or blue on a paler background.

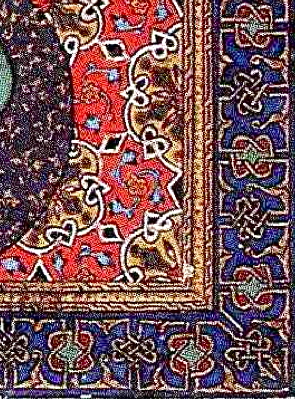

Figure 3: 1200-1300. Seldjuk. TIEM. Turkish Handwoven Carpets Vol I

Figure 4: 1200-1300. Seldjuk.

Figure 5: 1200-1300. Seldjuk?. Detail. H. Kircheim, Orient Stars

Figure 6: 1200-1300. Seldjuk.Konya Museum.Turkish Handwoven Carpets.HC II Ill. 166

Il-khanid period

In 1218-1221, Gengis Khan’s

Turco-Mongol armies made short work of the Kwaresm Empire (which itself

had shortly before destroyed the Great Seldjuk Empire in Persia), then

it was the turn of the Anatolian Sedjuks of Rum to bow to the

superiority of the Turco-Mongols. After the wanton massacres and

destruction of whole cities, the Mongol Il-Khans recreated, during one

century, the conditions for economic and artistic developments. There

are no known extant rugs from the Il-khanid period, only a few

rug-featuring miniatures. Interestingly, already in this early stage,

various kufic "letters" were used by the illustrators as border motifs

and all borders featured white (or pale) kufic on a darker background

(Figures 7-10).

Figure 7: 1330-1340, Il-khanid. The bier of Iskander. Tabriz school. Freer-Sackler.

Figure 8: 1330-1340. Il-khanid. The guest beats the mouse. Tabriz school. From a kalila wa Dimna. Istanbul.

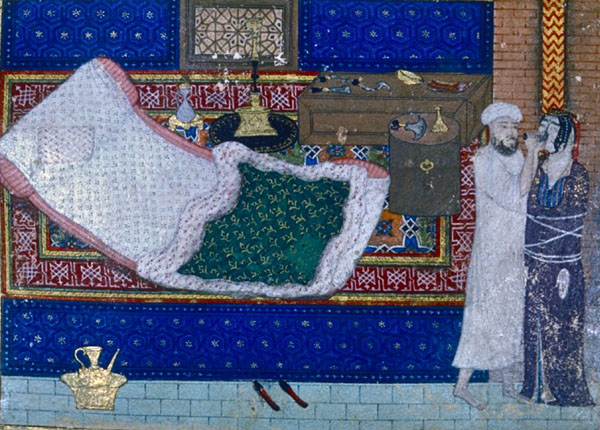

Figure 9. 1330-1340. Il-khanid. Old madam and young couple. From a kalila wa Dimna. Istanbul

Figure 10: 1330-1340. Il-khanid. Father teaching his sons. From a kalila wa Dimna. Istanbul.

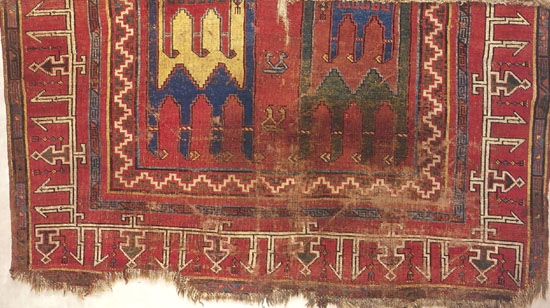

Between the il-khanid and Timurid periods

Several rugs with various kufic borders are also known from miniatures

painted during the troubled period following the demise of the

Il-khanid dynasty. (Figures 11-13).

Figure 11. 1370-1375. Chubanid period. Tabriz school. Thief beaten in the bedchamber. From a kalila wa Dimna. Istanbul Univ. Library

.

.

Figure 12: 1370-1375. Chubanid period.Tabriz school. Cobbler cuts the nose of barber’s wife. From a kalila wa Dimna. Topkapi. Istanbul

Figure 13: 1396. Jalayirid period. Baghdad school. Humay and Humayun. From a Khamsa.

Figure 11 is particularly important as a clue that the kufic borders derive directly from the kufic script and are not merely ornamental since, since, according to J. Bailey (6), this rug shows a perfectly readable kufic border. See also http://www.turkotek.com/misc_00130/kufic.htm

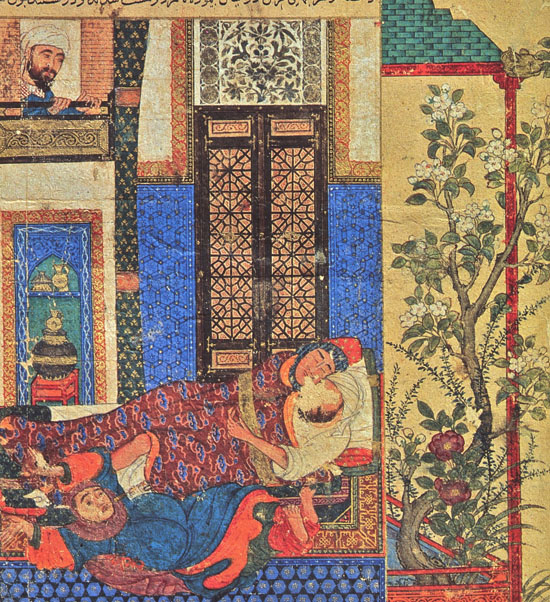

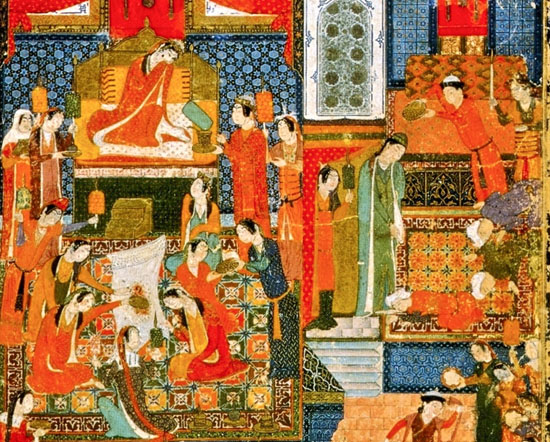

Timurid period

After Timur united Transoxiana,

Kwaresm, Iran, Afghanistan and parts of Eastern Anatolia under his

ruthless rule, kufik rug borders were promoted to something like an

"official standard", since from 1400 till about 1490 a very large

number of Timurid miniatures (for example Figures 15 - 21) featured

rugs which, independently of their field pattern, nearly always carried a kufic border, invariably with white script over a dark background (7, 8, 9).

The use of various scripts, especially kufic and square kufic (usually spelling God’s names and attributes) for decorative tiling on buildings was common in Islamic countries. One could argue that this style reached a peak in Timurid Iran, where mosques and madrasas were mostly covered with kufic tiling. Thus, the presence of kufic on Timurid rugs, the most important piece of furniture of the time, should not come too much as a surprise. We know of only one extant (supposedly) Timurid fragment (Figure 14).

Figure14: Timurid? fragment. 15th century. Benaki Museum, Athens

Figure 15: 1429. Timurid. Herat school. Baysungur in a garden. Detail

Figure 16: 1434-1440. Timurid. Herat school. Tahmina enters Rustam chamber. Detail.

Figure 17: 1427. Timurid. Herat school. Princes playing games. Detail. Berenson Collection.

Figure 18. 1488. Late Timurid period. Herat school. Party at the Court of Huseyn Mirza.Detail.

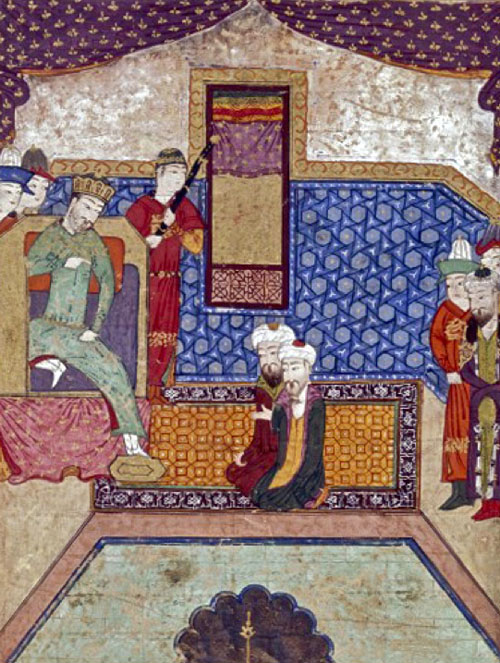

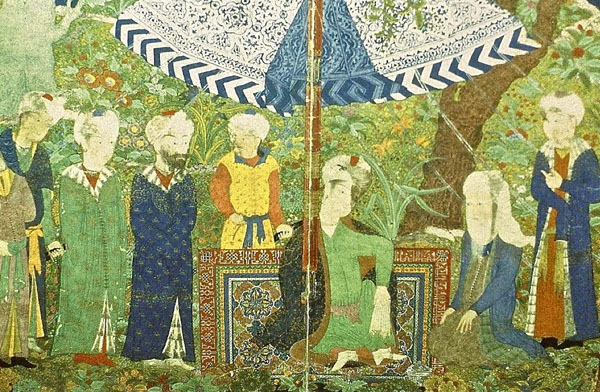

Figure 19. 1438. Timurid, Shiraz school. Güyük Khan granting an audience. Bibl. Nat. de France. Paris.

Figure 20: 1445-1446, Timurid. Herat school. Khusraw receives Farhad.

Figure 21: 1467-1468. Timurid. Herat school. Timur granting an audience in Balkh.

Figure 21 shows a Timurid miniature featuring a rare case of rug without a kufic border. Besides, the curvilinear pattern of the field featured in Figures 20 and 21 is similar to the style later imposed by the Safavid rulers, but was much less frequent than geometric patterns in Timurid rugs.

Meanwhile, the first carpet with kufic border appeared in a European painting, in 1423 in G. di Cecco’s "Marriage of the Virgin" (Figure 22). It was an "animal rug" similar to the one in Figure 5. Later, around 1460-1490, other kufic borders appeared in paintings of Mantegna (Figure 23) and Botticelli (Figure 24), both featuring small pattern Holbein fields (9). Verrocchio (Figure 25) and Ghirlandaio (Figure 26) came next, followed by an increasing number of painters throughout the sixteenth century.

Figure 22: 1423. G. di Cecco. Marriage of the Virgin. Detail. National Gallery, London.

Figure 23: 1457-1459. Mantegna. Virgin and Child. Detail. Small pattern Holbein field. San Zeno altarpiece. Verona.

Figure 24: 1460. Botticelli. F. de Montefeltre and Landino. Vatican

Figure 25: 1475. A. del Verrocchio and L. di Credi. Madonna with St John the Baptist. Detail. Pistoia Cathedral

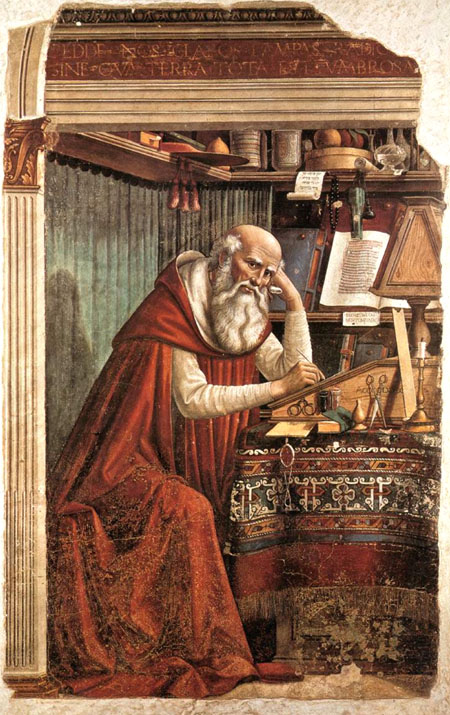

Figure 26: 1480. D. Ghirlandaio. St Jerome. Detail. Florence

Between the Timurid and the Safavid periods.

Back to Asia: After the fall of the Timurid Empire, the kitabkhana

illustrators of some of their former regional rivals and of Timurid

offsprings, like for example the Aq Koyunlu Turkomans (10), or the rulers of Gilan (11) kept illustrating their manuscripts with rugs featuring "kufic" borders.( Figures 27-28).

Figure 27: ca. 1500. Turkoman Aq Qoyunlu. Ya’qub Bey

Figure 28: 1493-1494. Gilan. Gurgin before Khusraw. Freer Sackler.

Others, like the Uzbek (12) and Safavid kitabkhana illustrators preferred curvilinear and floral patterns for the carpet fields and borders and all but dropped the kufic borders. The curvilinear floral patterns were very common in architectural decoration, in manuscript illustrations (the Koran, for example), but until the sixteenth century they did not seem to have been much used for rugs, if we can trust the extant Persian miniatures. In Safavid Persia, the new curvilinear rug style was imposed by Shah Abbas himself to the royal weavers and to the kitabkhana painters. One can suppose that, again, regime propaganda and differentiation from previous dynasties played a role in his decision.

Figure 29: 1538. Uzbeck. Bokhara school. Freer Sackler

Meanwhile in Europe, during the end of the 15th century and the first half of the 16th century, a pretty large number of rugs with kufic borders appeared in paintings (Figures 30-33). A number of rugs from this period are still extant (Figure 34). Unless I err, none has ever been attributed to Persia, but only - perhaps by default - to Ottoman Anatolia and to "para Mamluk" workshops, the latter designation being a mere smoke screen for our ignorance, since there is still no agreement among the experts about their true origin (13).

Figure 30: 1483. D. Ghirlandaio. Virgin and Child. Detail. Uffizi. Florence

Figure 31: A: 1486. C. Crivelli. Annunciation with St Emidius. Detail. National Gallery. London; B: ca.1500. Master of the Sisla. Annunciation. Detail. Prado. Madrid; C: 1500-1530. Unknown painter. Virgin and Child. Detail. Liverpool; D: ca.1500. Martini da Udine. St Mark enthroned. Detail. Duomo di Udine

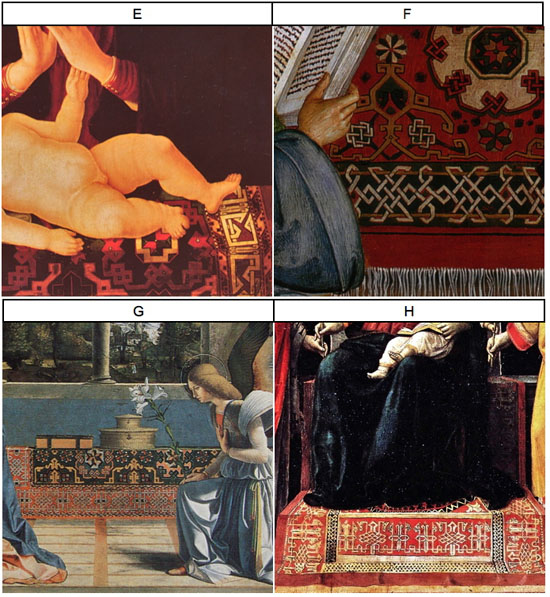

Figure 32: E: ca.1500. J. da Valenza. Virgin and Child. Detail. Budapest; F: 1502-1508. Il Pinturicchio. Pope Pius II at the Mantova Congress. Detail. Siena; G: 1508. A. Previtali. Annunciation. Detail. Vittorio Veneto; H: 1510. V. Foppa.Virgin and Child. Detail. Pala dei Mercanti. Brescia.

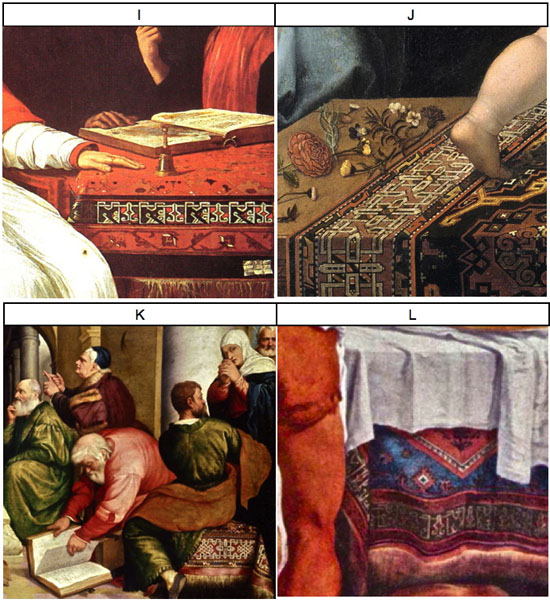

Figure 33: I: 1516. S. del Piombo. Cardinal Bandinello Sauli. Detail. National Gallery of Art. Washington; J: 1522. B. van Orley. Holy family. Detail. Prado. Madrid; K: 1539. J.Bassano (da Ponte). Christ among the Doctors. Detail. Ashmolean Museum. Oxford; L: 1555. J. Bassano (da Ponte). Beheading of John the Baptist. Detail. Kopenhagen.

Figure 34: T1: 15th-16th century. Para-mamluk. Detail. W. Denny. Anatolian Carpets;

T2: 16th century. Small pattern Holbein. Detail. Anatolia?. HALI;

T3: 16th centuty. Bergama. Detail. Turkish Handwoven Carpets, catalog #1;

T4: 16th century. Ushak. Lotto field pattern. Detail. St Louis Art Museum.

T5: 16th century. Ushak. Bellini field pattern. Berlin; T6: 16th century. Bergama. Large pattern Holbein. Berlin.

Towards the end of the sixteenth century, extant kufic rugs (Figure

35) and paintings featuring this kind of rugs (Figure 36) became

scarce, except perhaps in the Caucasus.

Figure 35, T9 shows a rare case of kufic "script" woven in the field (18th century).

Figure 35: T7: 17th century. Para-Mamluk. Detail; T8: 17th century. Bergama. Lotto field pattern. Detail. M. Tabibnia. Tappeti Classici d’Oriente del XVI e XVII secolo; T9: 18th century. Konya prayer rug. Kufic script in the field. Detail. Turkish Handwoven Carpets. Catalog #4

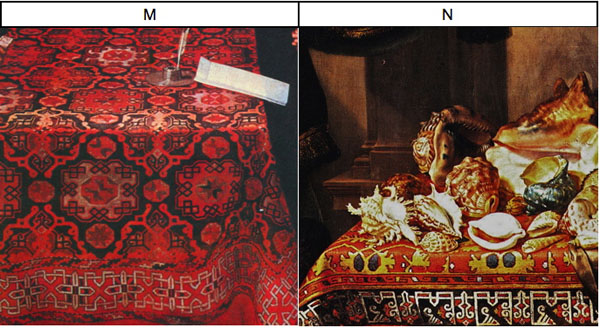

Figure 36: M: 1604. Unknown painter. The Somerset House Conference. Detail. National Gallery. London; N: ca.1700. B. Bimbi. Still life. Detail. Siena

The huge (and probably hugely expensive) rug featured in Figure 36 M was perhaps much older than the painting and not necessarily representative of the production of the end of the sixteenth century. It may have been part of the large 1547 inventory of King Henry VIII of England.

Caucasus weavers from the Baku/Schirvan area were, as far as I know, about the only ones who kept weaving rugs with "kufic" borders (14) until recently. I think it is rather unlikely that this border motif was merely adopted for base commercial reasons under European influence, since a number of extant rugs featuring it are dated (5) from the 19th century, when Caucasian rugs were still practically unknown in Europe and the rug literature was still in infancy (Figure 37).

Figure 37: T10: 19th century. Caucasus. Kuba. D. Eder. Orient Teppiche. Band 1. Kaukasische Teppiche; T11: 19th century. Caucasus. Kuba. U. Schurmann. Caucasian Rugs; T12: 19th century. Caucasus. Kuba. D. Eder. Orient Teppiche. Band 1. Kaukasische Teppiche; T13: 19th century. Caucasus. Schirvan. D. Eder. Orient Teppiche. Band 1. Kaukasische Teppiche.

NOTES: