| #1 David R E Hunt |

August 13th, 2015 06:35 AM |

IHBS/ICOC Exhibition at David Zahirpour Oriental Rugs

Hi Folks

On August 8th 2015 our local IHBS Washington DC based rug club hosted a juried exhibition of member holdings

in conjunction with the International Conference of Oriental Carpets at David Zahirpour's Oriental Rugs in the

Friendship Heights neighborhood of Washington D.C..

The exhibition was held at the conclusion of ICOC programme, and by the time

I had arrived the space was already standing room only, do I decided to take a brief walk and come back in a half hour.

Color, condition and Caucasian seem as good a summation as any of the exhibit, in which the rich greens of weaving

from the Caucasian production centers figured prominent, owning to the strength of member collections in this area.

A majority of pieces were in outstanding condition.

Standouts included the above Shirvan and a Zeichour sporting another set of phenomenal greens,

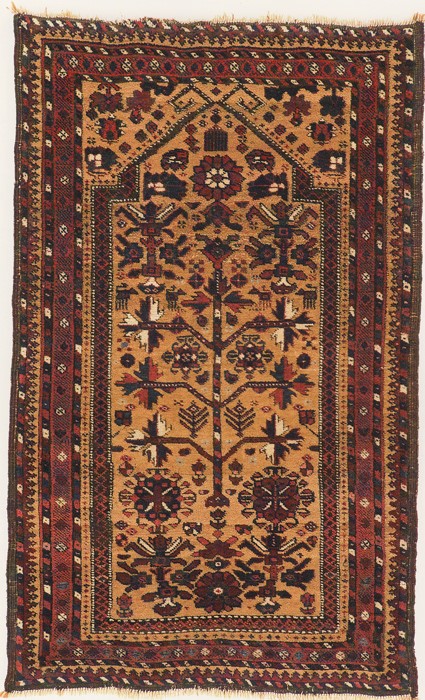

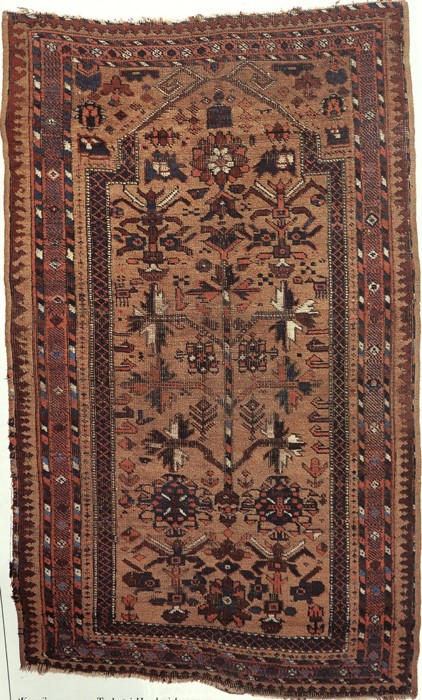

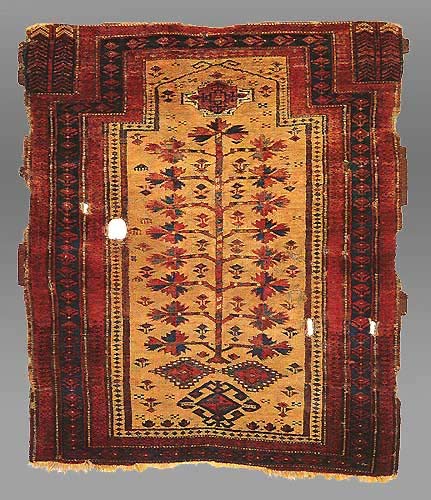

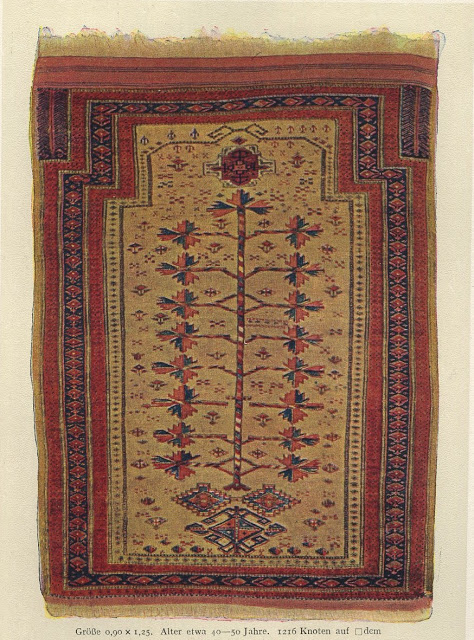

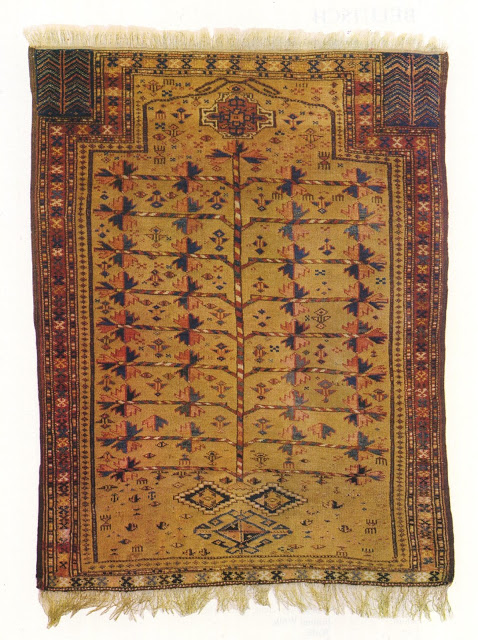

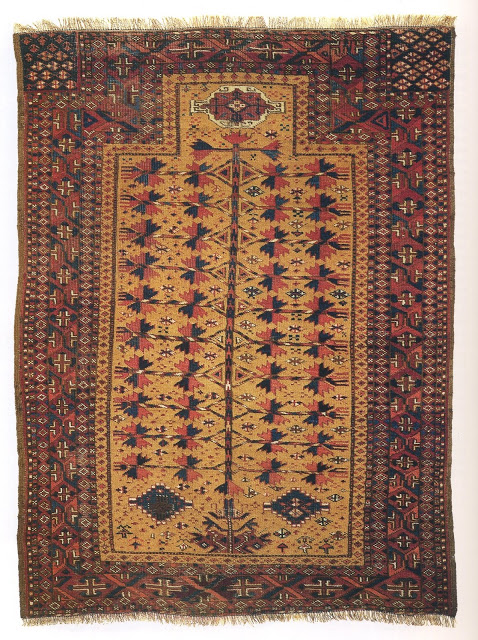

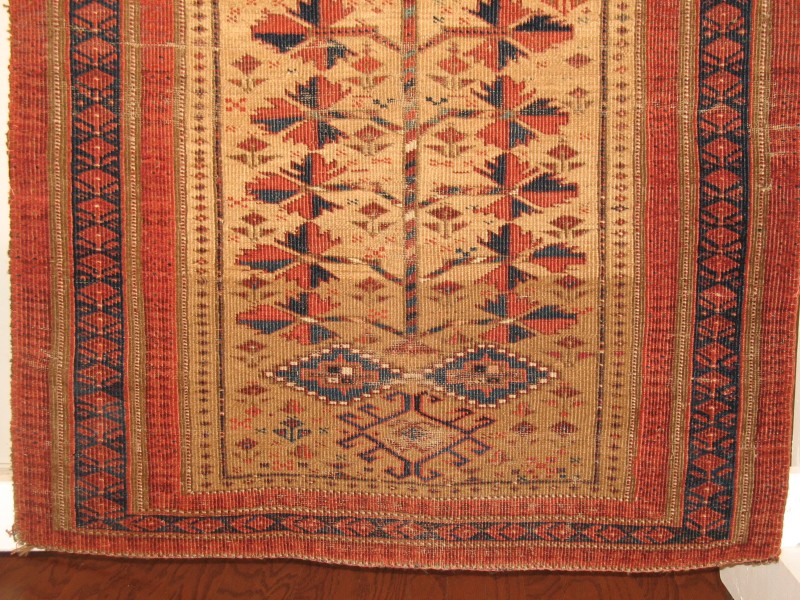

an Eagle Gul main carpet in pristine condition,an interesting permution of the camel ground tree of life rug,

a striking Suzani and a Salor Turkmen torba.

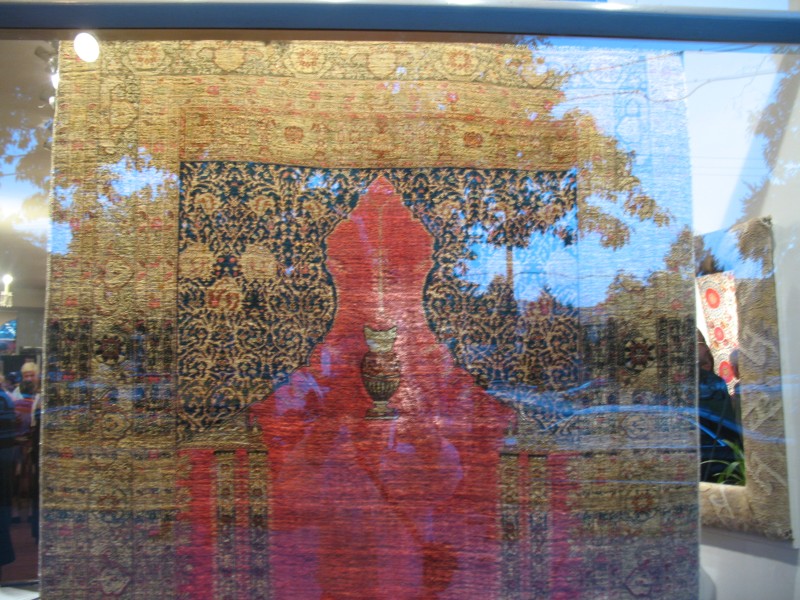

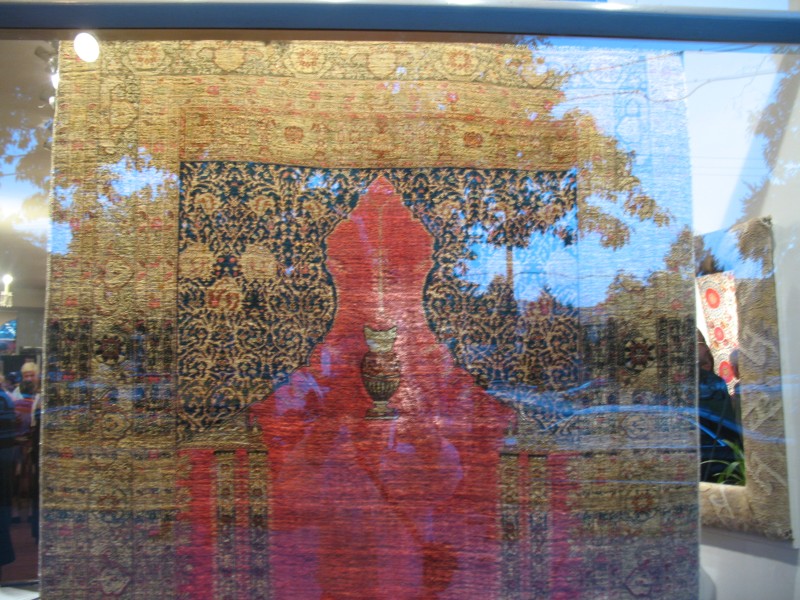

Lighting was a challenge here in regards to photography, let alone with the variety of photographing textiles themselves,

witness my attempts at photographing the star of the show in the front window.

On August 8th 2015 our local IHBS Washington DC based rug club hosted a juried exhibition of member holdings

in conjunction with the International Conference of Oriental Carpets at David Zahirpour's Oriental Rugs in the

Friendship Heights neighborhood of Washington D.C..

The exhibition was held at the conclusion of ICOC programme, and by the time

I had arrived the space was already standing room only, do I decided to take a brief walk and come back in a half hour.

Color, condition and Caucasian seem as good a summation as any of the exhibit, in which the rich greens of weaving

from the Caucasian production centers figured prominent, owning to the strength of member collections in this area.

A majority of pieces were in outstanding condition.

Standouts included the above Shirvan and a Zeichour sporting another set of phenomenal greens,

an Eagle Gul main carpet in pristine condition,an interesting permution of the camel ground tree of life rug,

a striking Suzani and a Salor Turkmen torba.

Lighting was a challenge here in regards to photography, let alone with the variety of photographing textiles themselves,

witness my attempts at photographing the star of the show in the front window.

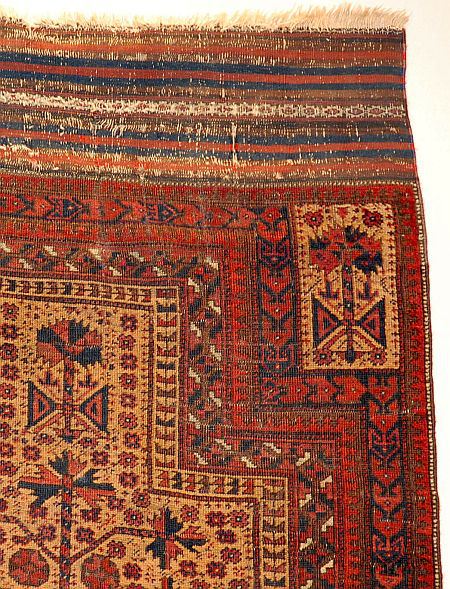

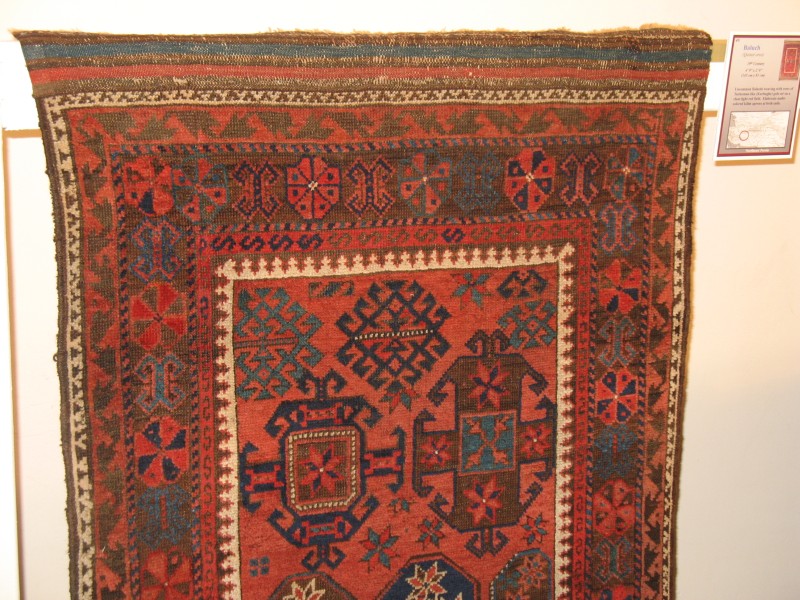

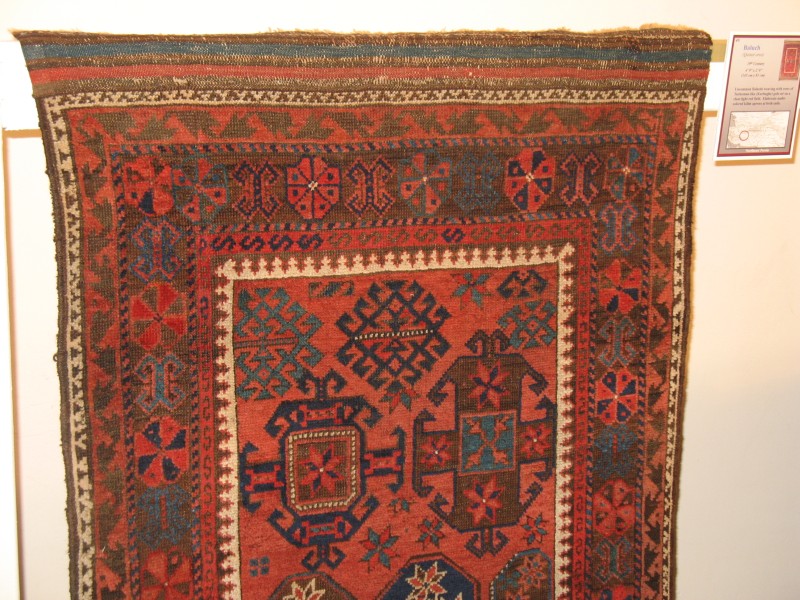

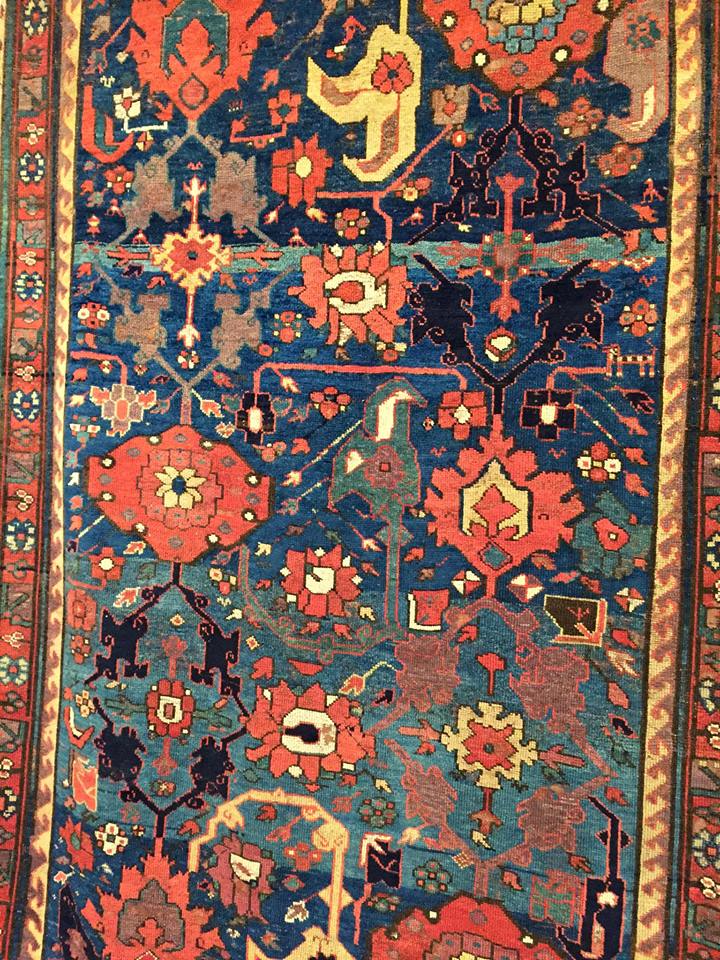

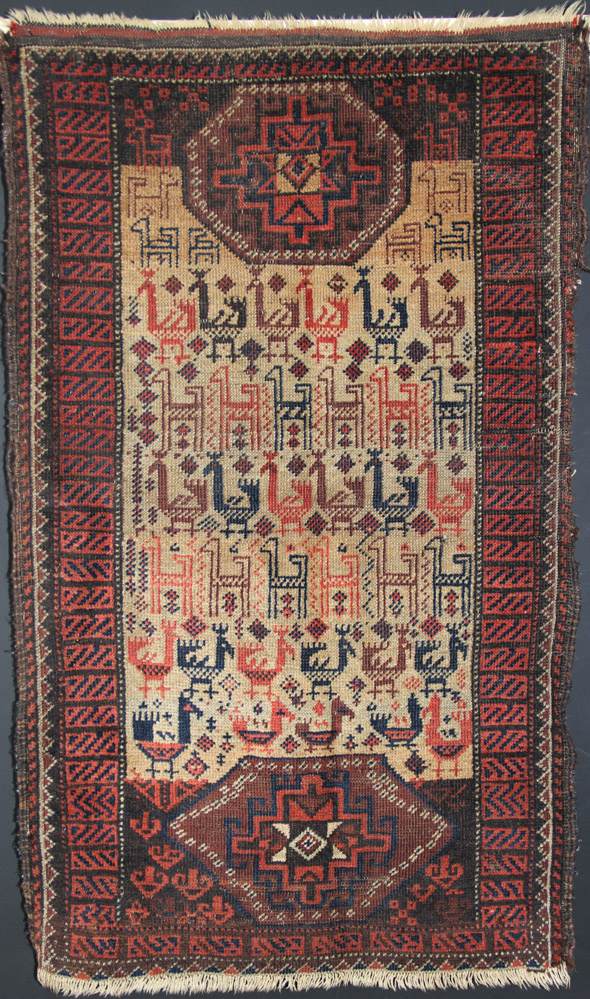

Turkmen palette cleanser) here

are two partial views of a decidedly non-fragmented Kurdish Sauj Bulagh

rug that held my attention for quite a while at the reception. I was

going on about it quite enthusiastically to an IHBS stalwart who just

smiled contentedly and said, "I agree; it's mine." As were a number of

the other choice pieces in the room.

Turkmen palette cleanser) here

are two partial views of a decidedly non-fragmented Kurdish Sauj Bulagh

rug that held my attention for quite a while at the reception. I was

going on about it quite enthusiastically to an IHBS stalwart who just

smiled contentedly and said, "I agree; it's mine." As were a number of

the other choice pieces in the room.

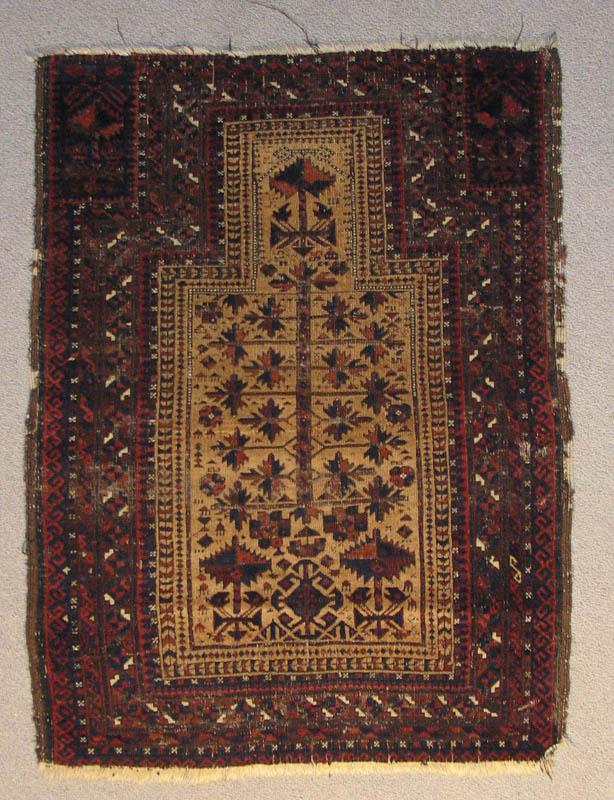

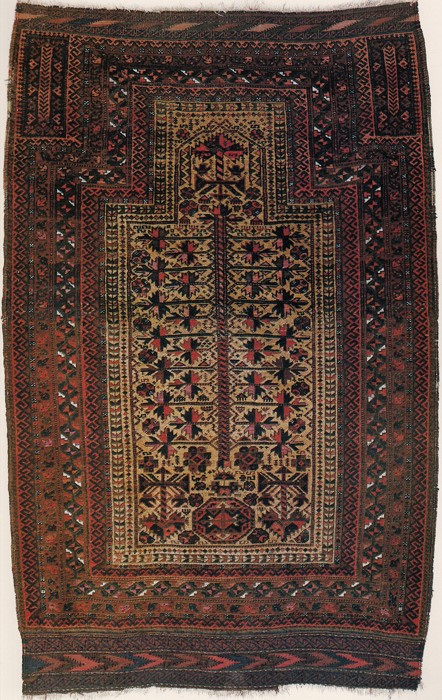

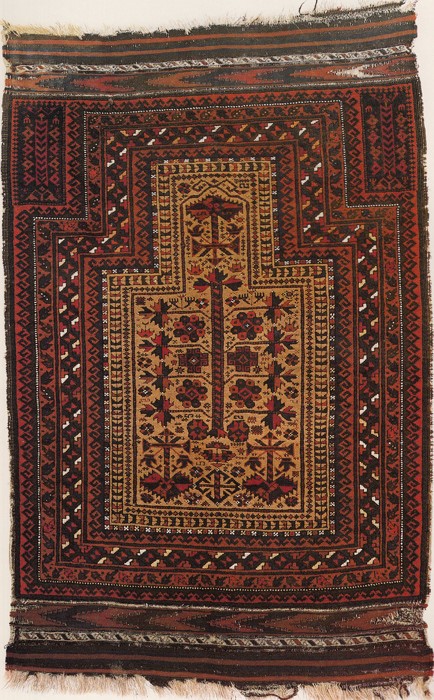

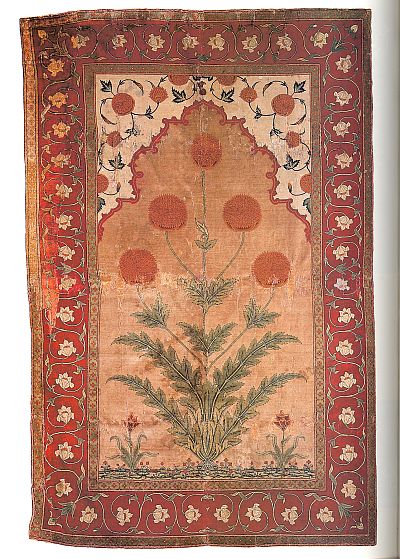

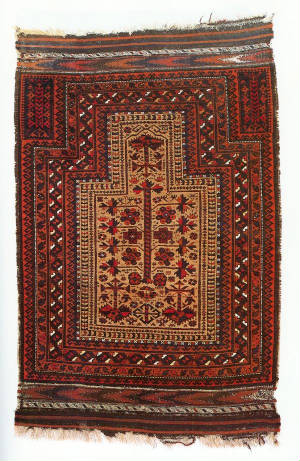

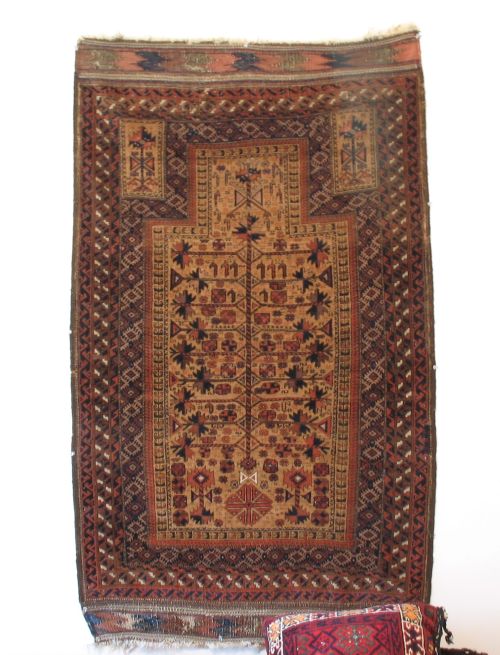

Well, there's a related issue, which is, what

do we mean when we say Baluch. If Konieczny's book were the only

reference you had ever seen, all of these would be rejected as Baluch.

The Persian-speaking Jamshidi and Kawdani of NW Afghanistan are

generally considered Chahar-Aimaq and not - rigorously - Baluch. Ditto

for Timuri and Taimani. And folks, to me all of these tree-of-life

pieces look like material from that region, not from Balochistan.

Plenty of opportunity for mixing of cultures, aesthetics, and commerce.

And a fine pile weave not generally seen from the southern "true"

Baluch.

Well, there's a related issue, which is, what

do we mean when we say Baluch. If Konieczny's book were the only

reference you had ever seen, all of these would be rejected as Baluch.

The Persian-speaking Jamshidi and Kawdani of NW Afghanistan are

generally considered Chahar-Aimaq and not - rigorously - Baluch. Ditto

for Timuri and Taimani. And folks, to me all of these tree-of-life

pieces look like material from that region, not from Balochistan.

Plenty of opportunity for mixing of cultures, aesthetics, and commerce.

And a fine pile weave not generally seen from the southern "true"

Baluch.