| #1 Joel Greifinger |

November 18th, 2013 12:21 AM |

It's a Kurd, It's a Flame, It's...Sauj

Bulagh?

A couple of fairly recent rug additions have revved up a quandary

that I've had for a while: what designates the boundaries of the

widely-assigned category, Sauj Bulagh?

In 2009, Rippon-Boswell had this description in their catalogue:

“Sauj Bulag” is now an established generic term for Kurdish carpets made around Lake Urmia; the name derives from a town where such pieces, made in the surrounding area, were sold in the bazaar... Sauj Bulags are considered beautiful Kurdish pieces due to their brilliant colours (and often) the corroded brown ground of the field."

William Eagleton writes, "The illusive Sauj Bulaq (pronounced 'Sa Blah') rugs of the late 19th and 20th century, usually with reddish wefts and deep pile colours, should be placed in this (i.e. "Western Mountain") category since they were woven in the mountains near Sauj Bulaq, modern Mahabad. However, rug books give such a variety of conflicting data on the structure and designs of Sauj Bulaq rugs..."

At an exhibit of Kurdish weaving in 2000 where six Sauj Bulaghs were on display, the description of these read: "United by a common palette and secondary border treatments, the field patterns are all different." and a leading New York dealer, acknowledging the wide range of field designs on rugs they designate as Sauj Bulagh comments that nonetheless, "the particular range of colors – autumnal oranges with soft blues, greens, and aubergine is now recognized a distinctive Kurdish palette of the Sauj Bulag region in Northwest Iran."

With all of the variation, there are elements that are common to all of these rugs. Like other Kurdish rugs, they are woven with the symmetrical knot. The knotting is generally coarse to moderate and the back of the rug is generally flat or flat-ish. While the foundation of some of the earliest rugs of the type are cotton, from the beginning of the 19th century on they are wool. Wefts are often (but not always) a light red color through all or some of the rug.

With all of the variety of field motifs, there are nonetheless a few that appear characteristic of many rugs designated as Sauj Bulagh. Most identified with this group is the so-called "flaming palmette". However, stepped diamond, "tuning fork", floral lattice and a lozenge design that Burns calls ashlik (as opposed to ashik?) are also clearly associated.

Probably the most indicative are two secondary border treatments: particular versions of medachyl (running dog) and vine meander designs.

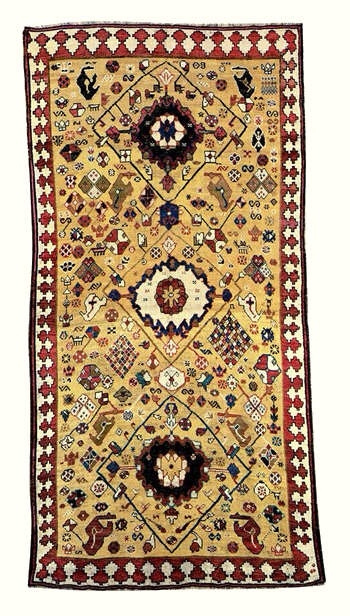

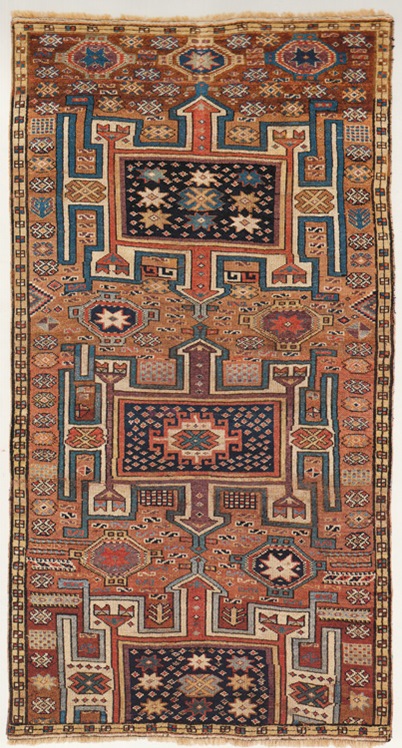

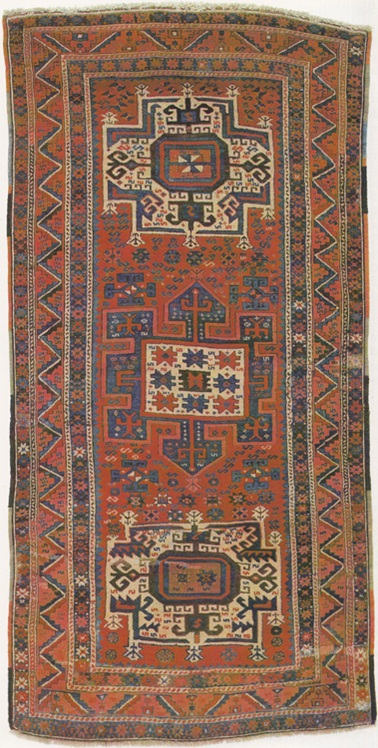

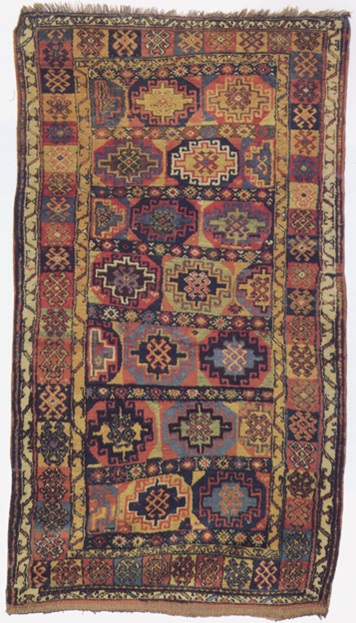

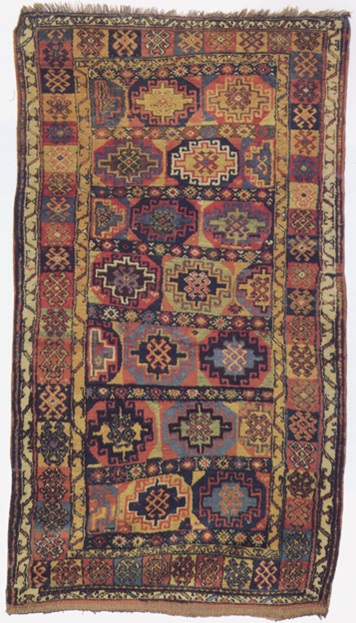

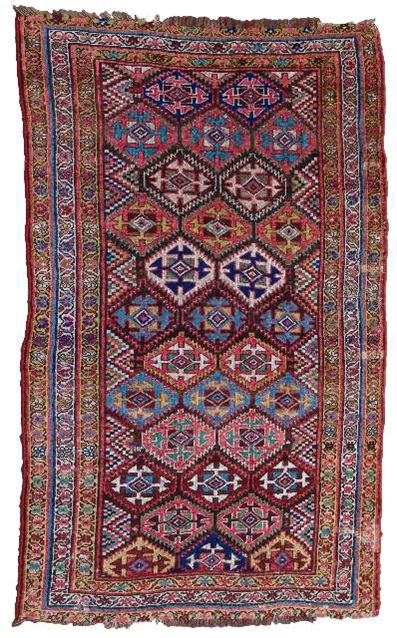

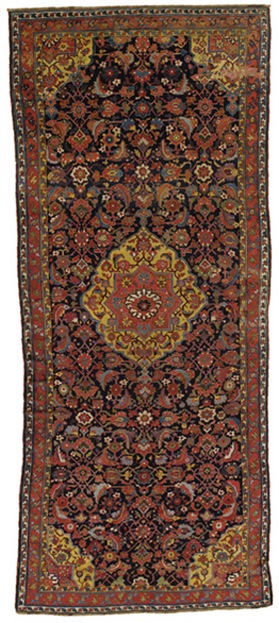

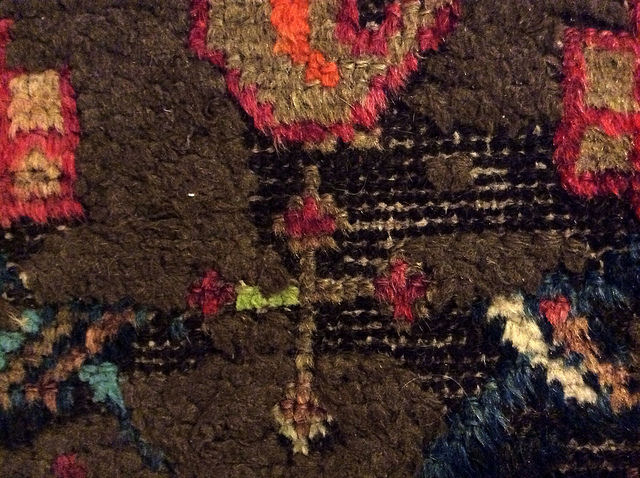

Now, the first of my additions just happens to have both types of secondary borders. Combined with the corroded brown in the field, light red wefts, a flat back and ashlik lozenge, this is surely what is widely termed Sauj Bulagh:

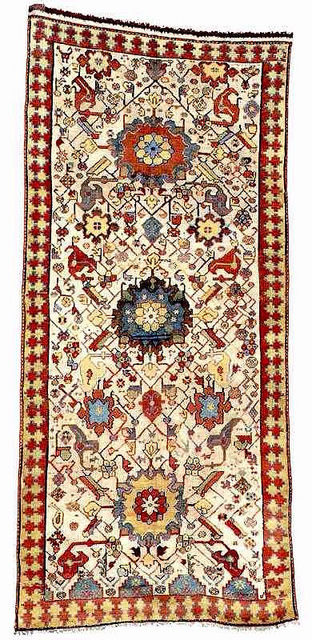

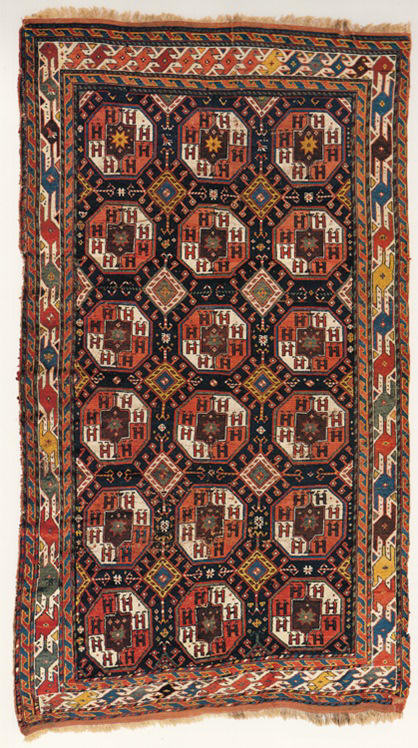

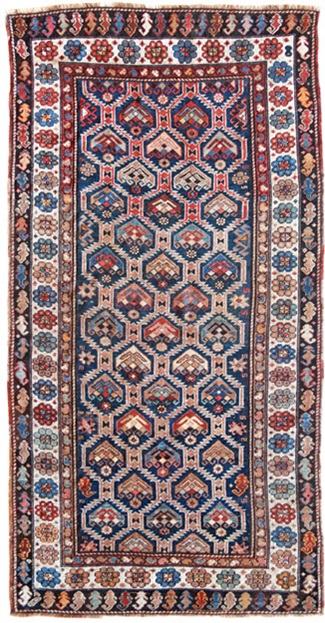

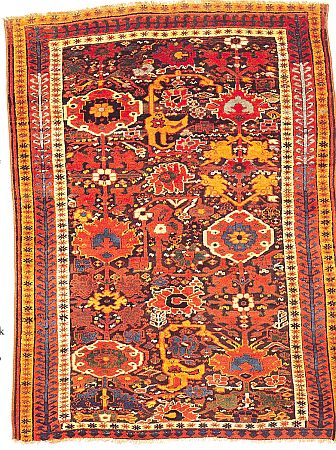

Design-wise, this rug has a great deal in common with Burns's "Ashlik" Sa'uj Bulagh rug (#49 in Antique Rugs of Kurdistan). In terms of range and intensity of color, well that's another story. The Burns rug has fifteen colors, mine a none-too-shabby twelve (gold, white, medium purple, turquoise, gray, orange, two reds, two browns and two blues). Here's the Burns:

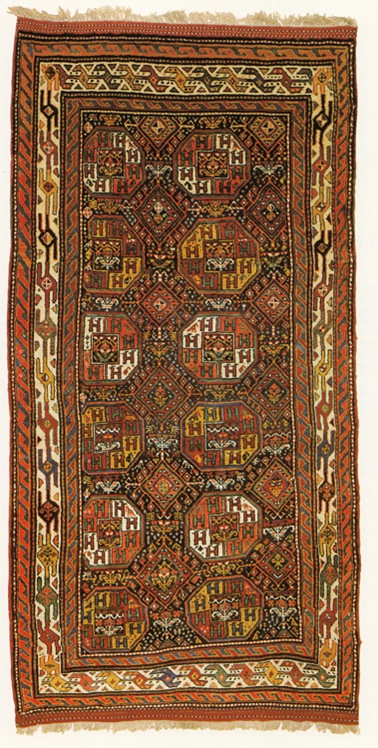

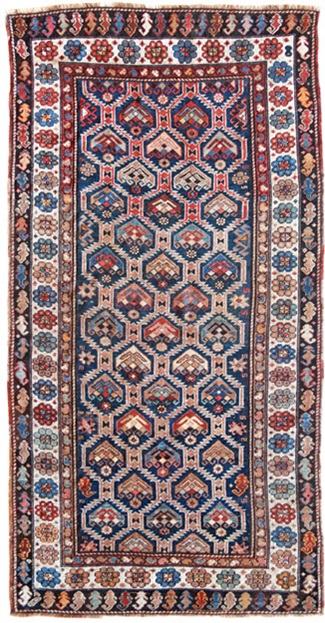

And here's one with ashlik posted on Turkotek years back by Bob Kent. Notice the multiple vine meander borders:

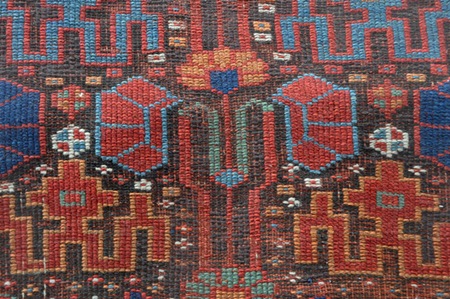

Flaming palmettes are probably the most widely recognized indicator that a rug should be called Sauj Bulagh. Probably the best known of these is this Meyer-Muller Collection rug. If you look close, you can see the secondary vine meander on a blue ground:

A rare instance where you get the combination of flaming palmettes and both the running dog and vine meander borders, is in this rug:

These are some other flaming palmette models. The first has a common main border for the type:

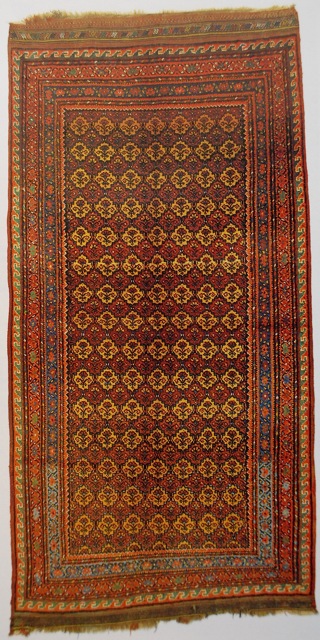

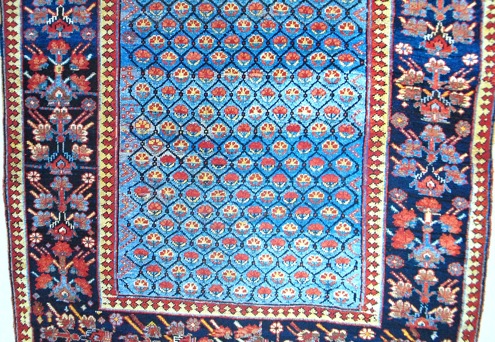

While the corroded brown field is a strong Sauj Bulagh indicator, not all of the rugs that get this designation (by auction houses, widely recognized dealers or rug book authors) have brown as the background field color. Some have red, a few yellow. One larger group has blue, as with these:

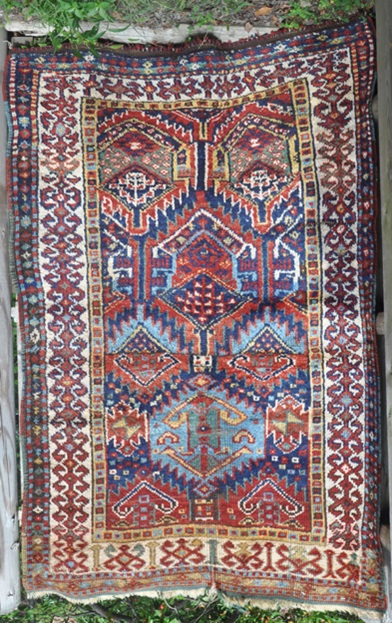

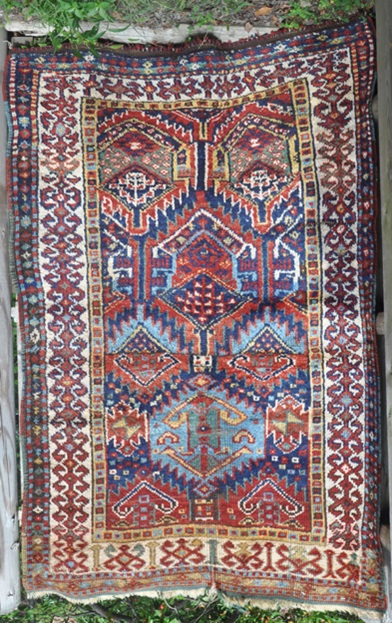

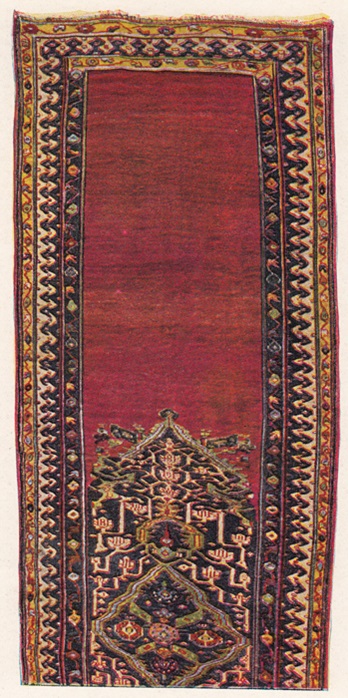

Which brings me to my second recent addition. I call it "Wild Thing". It has many of the elements of rugs widely called Sauj Bulagh. The palette, with fourteen very saturated colors, is certainly of the type. The pile is long, very lustrous and extremely silky. It has flaming palmettes (wildly drawn, but quite recognizable) going in both directions. Both the 'exuberant' drawing and the bi-directional motifs are seen on some other Sauj Bulagh rugs. Some of the wefts are light red, but others are brown and still others are green. Neither the major or minor borders are particularly characteristic, though the major border is a funkier rendition of the motif found on both my other rug and the Burns rug.

Sauj Bulagh?

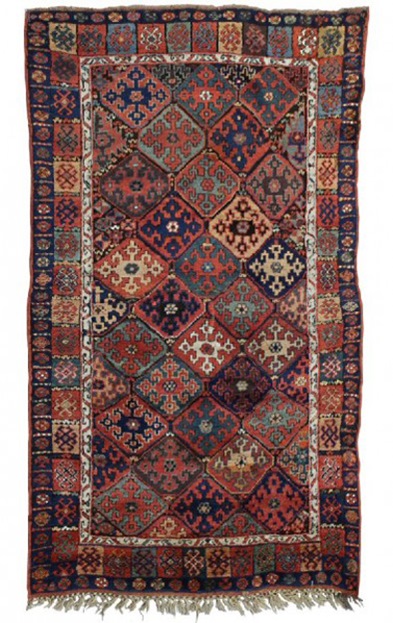

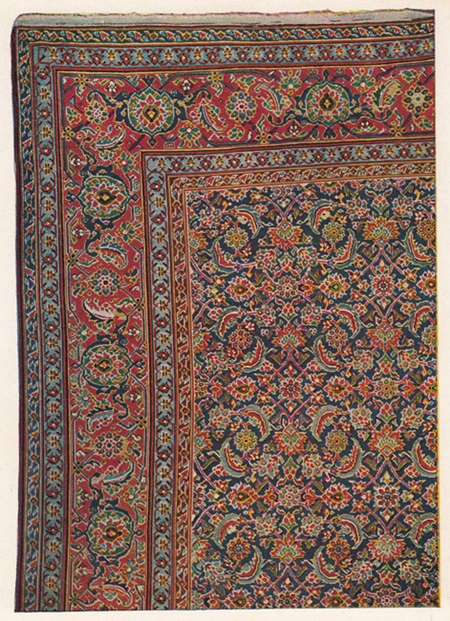

And here's a rug that was published in the Chicago Rug Society's Mideast Meets Midwest catalogue as possibly Kordi, that I now wonder if we'd call Sauj Bulagh. Notice it has the secondary vine meander border and the same motif in the major border as a number of the rugs above. The back is flat and it has thirteen colors:

What do you think? Are the last two rugs Sauj Bulagh, too?

Is all of this merely another instance of 'market category-creep' because "Sauj Bulagh" fetches higher prices than plain old "Northwest Persian Kurdish"?

Joel Greifinger

In 2009, Rippon-Boswell had this description in their catalogue:

“Sauj Bulag” is now an established generic term for Kurdish carpets made around Lake Urmia; the name derives from a town where such pieces, made in the surrounding area, were sold in the bazaar... Sauj Bulags are considered beautiful Kurdish pieces due to their brilliant colours (and often) the corroded brown ground of the field."

William Eagleton writes, "The illusive Sauj Bulaq (pronounced 'Sa Blah') rugs of the late 19th and 20th century, usually with reddish wefts and deep pile colours, should be placed in this (i.e. "Western Mountain") category since they were woven in the mountains near Sauj Bulaq, modern Mahabad. However, rug books give such a variety of conflicting data on the structure and designs of Sauj Bulaq rugs..."

At an exhibit of Kurdish weaving in 2000 where six Sauj Bulaghs were on display, the description of these read: "United by a common palette and secondary border treatments, the field patterns are all different." and a leading New York dealer, acknowledging the wide range of field designs on rugs they designate as Sauj Bulagh comments that nonetheless, "the particular range of colors – autumnal oranges with soft blues, greens, and aubergine is now recognized a distinctive Kurdish palette of the Sauj Bulag region in Northwest Iran."

With all of the variation, there are elements that are common to all of these rugs. Like other Kurdish rugs, they are woven with the symmetrical knot. The knotting is generally coarse to moderate and the back of the rug is generally flat or flat-ish. While the foundation of some of the earliest rugs of the type are cotton, from the beginning of the 19th century on they are wool. Wefts are often (but not always) a light red color through all or some of the rug.

With all of the variety of field motifs, there are nonetheless a few that appear characteristic of many rugs designated as Sauj Bulagh. Most identified with this group is the so-called "flaming palmette". However, stepped diamond, "tuning fork", floral lattice and a lozenge design that Burns calls ashlik (as opposed to ashik?) are also clearly associated.

Probably the most indicative are two secondary border treatments: particular versions of medachyl (running dog) and vine meander designs.

Now, the first of my additions just happens to have both types of secondary borders. Combined with the corroded brown in the field, light red wefts, a flat back and ashlik lozenge, this is surely what is widely termed Sauj Bulagh:

Design-wise, this rug has a great deal in common with Burns's "Ashlik" Sa'uj Bulagh rug (#49 in Antique Rugs of Kurdistan). In terms of range and intensity of color, well that's another story. The Burns rug has fifteen colors, mine a none-too-shabby twelve (gold, white, medium purple, turquoise, gray, orange, two reds, two browns and two blues). Here's the Burns:

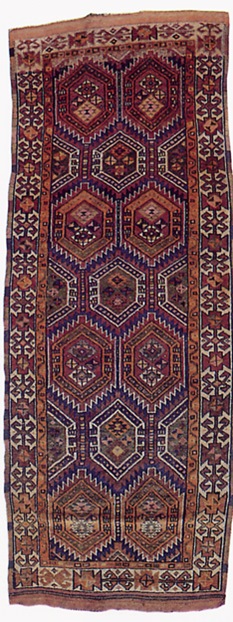

And here's one with ashlik posted on Turkotek years back by Bob Kent. Notice the multiple vine meander borders:

Flaming palmettes are probably the most widely recognized indicator that a rug should be called Sauj Bulagh. Probably the best known of these is this Meyer-Muller Collection rug. If you look close, you can see the secondary vine meander on a blue ground:

A rare instance where you get the combination of flaming palmettes and both the running dog and vine meander borders, is in this rug:

These are some other flaming palmette models. The first has a common main border for the type:

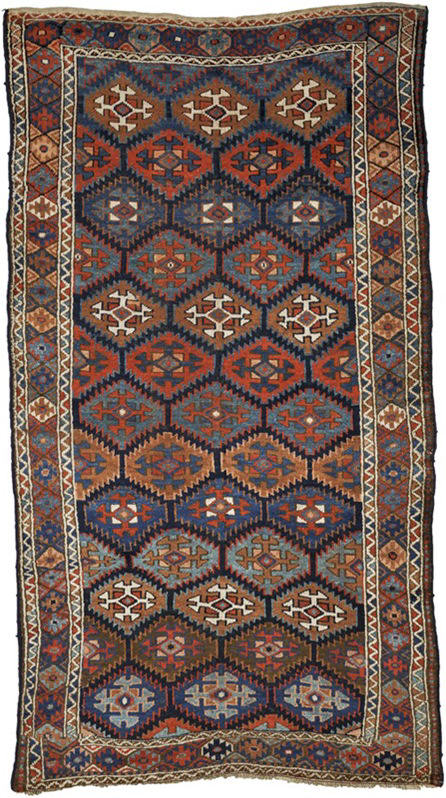

While the corroded brown field is a strong Sauj Bulagh indicator, not all of the rugs that get this designation (by auction houses, widely recognized dealers or rug book authors) have brown as the background field color. Some have red, a few yellow. One larger group has blue, as with these:

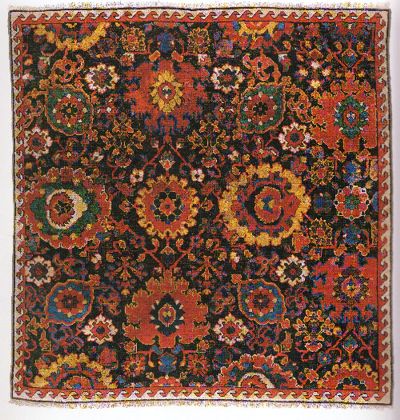

Which brings me to my second recent addition. I call it "Wild Thing". It has many of the elements of rugs widely called Sauj Bulagh. The palette, with fourteen very saturated colors, is certainly of the type. The pile is long, very lustrous and extremely silky. It has flaming palmettes (wildly drawn, but quite recognizable) going in both directions. Both the 'exuberant' drawing and the bi-directional motifs are seen on some other Sauj Bulagh rugs. Some of the wefts are light red, but others are brown and still others are green. Neither the major or minor borders are particularly characteristic, though the major border is a funkier rendition of the motif found on both my other rug and the Burns rug.

Sauj Bulagh?

And here's a rug that was published in the Chicago Rug Society's Mideast Meets Midwest catalogue as possibly Kordi, that I now wonder if we'd call Sauj Bulagh. Notice it has the secondary vine meander border and the same motif in the major border as a number of the rugs above. The back is flat and it has thirteen colors:

What do you think? Are the last two rugs Sauj Bulagh, too?

Is all of this merely another instance of 'market category-creep' because "Sauj Bulagh" fetches higher prices than plain old "Northwest Persian Kurdish"?

Joel Greifinger

What does seem clear, is that in the

last twenty years or so, some rugs that seem to display some family

resemblance based on structure, palette, wool quality, handle, field and

border designs and particularly brown field corrosion have become

established as a recognized (and valued) market

category.

What does seem clear, is that in the

last twenty years or so, some rugs that seem to display some family

resemblance based on structure, palette, wool quality, handle, field and

border designs and particularly brown field corrosion have become

established as a recognized (and valued) market

category.

there have been

Kurdish Christians, mostly Nestorians, living in Kurdistan for a long

time. Whether they wove rugs, I don't know. However, John Joseph in his

The Modern Assysians of the Middle East wrote that these Nestorians

were "scarcely distinguishable from the Muslim neighbors who were

interspersed among but not intermingled with them." He points out their

"uniformity of custom" in all but religious practices, including

"industry". Perhaps this included weaving.

there have been

Kurdish Christians, mostly Nestorians, living in Kurdistan for a long

time. Whether they wove rugs, I don't know. However, John Joseph in his

The Modern Assysians of the Middle East wrote that these Nestorians

were "scarcely distinguishable from the Muslim neighbors who were

interspersed among but not intermingled with them." He points out their

"uniformity of custom" in all but religious practices, including

"industry". Perhaps this included weaving.